This is “Key Framework: The Five Forces of Industry Competitive Advantage”, section 2.4 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.4). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.4 Key Framework: The Five Forces of Industry Competitive Advantage

Learning Objectives

- Diagram the five forces of competitive advantage.

- Apply the framework to an industry, assessing the competitive landscape and the role of technology in influencing the relative power of buyers, suppliers, competitors, and alternatives.

Professor and strategy consultant Gary Hamel once wrote in a Fortune cover story that “the dirty little secret of the strategy industry is that it doesn’t have any theory of strategy creation.”G. Hamel, “Killer Strategies that Make Shareholders Rich,” Fortune, June 23, 1997. While there is no silver bullet for strategy creation, strategic frameworks help managers describe the competitive environment a firm is facing. Frameworks can also be used as brainstorming tools to generate new ideas for responding to industry competition. If you have a model for thinking about competition, it’s easier to understand what’s happening and to think creatively about possible solutions.

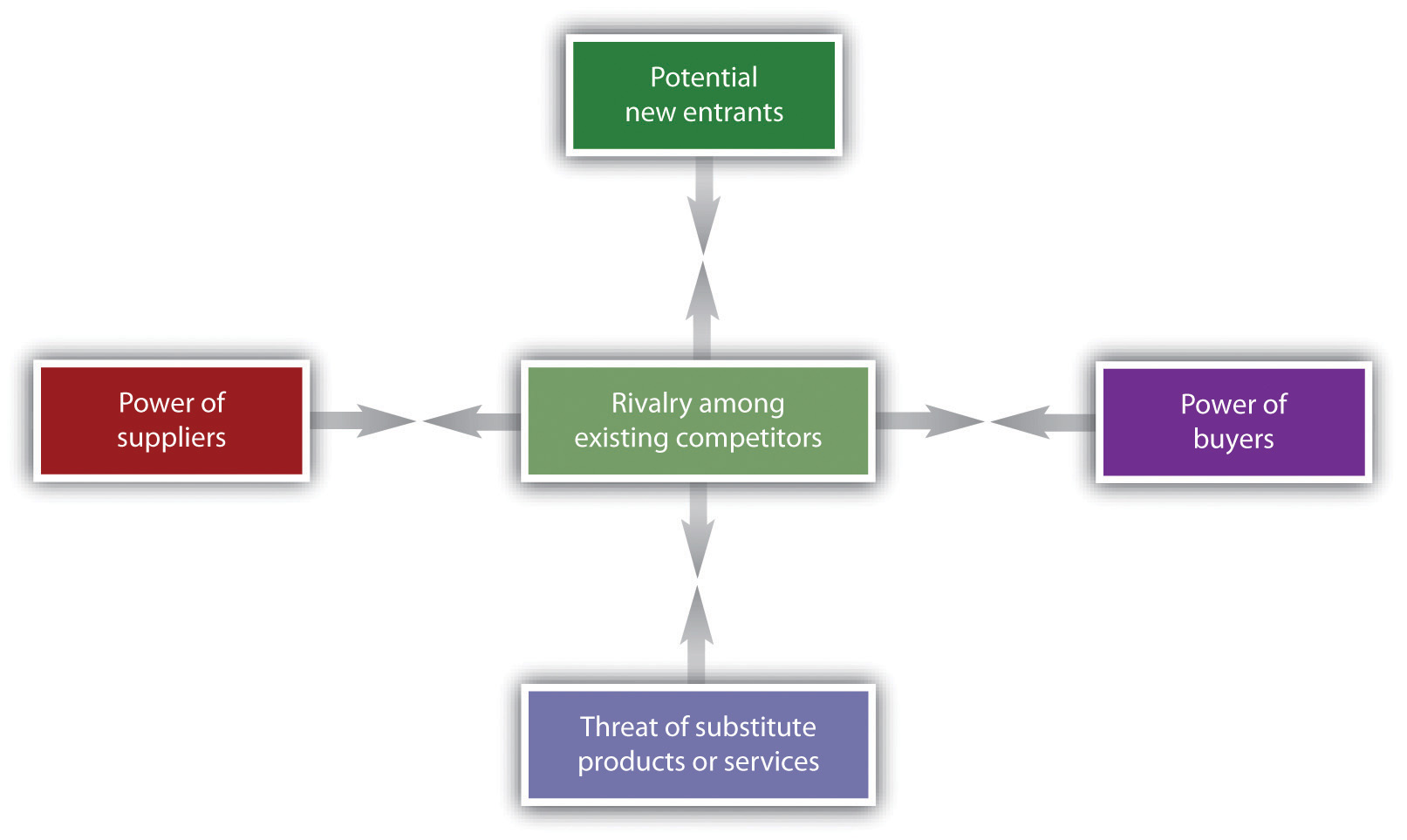

One of the most popular frameworks for examining a firm’s competitive environment is Porter’s five forcesAlso known as Industry and Competitive Analysis. A framework considering the interplay between (1) the intensity of rivalry among existing competitors, (2) the threat of new entrants, (3) the threat of substitute goods or services, (4) the bargaining power of buyers, and (5) the bargaining power of suppliers., also known as the Industry and Competitive Analysis. As Porter puts it, “analyzing [these] forces illuminates an industry’s fundamental attractiveness, exposes the underlying drivers of average industry profitability, and provides insight into how profitability will evolve in the future.” The five forces this framework considers are (1) the intensity of rivalry among existing competitors, (2) the threat of new entrants, (3) the threat of substitute goods or services, (4) the bargaining power of buyers, and (5) the bargaining power of suppliers (see Figure 2.6 "The Five Forces of Industry and Competitive Analysis").

Figure 2.6 The Five Forces of Industry and Competitive Analysis

New technologies can create jarring shocks in an industry. Consider how the rise of the Internet has impacted the five forces for music retailers. Traditional music retailers like Tower and Virgin found that customers were seeking music online. These firms scrambled to invest in the new channel out of what is perceived to be a necessity. Their intensity of rivalry increases because they not only compete based on the geography of where brick-and-mortar stores are physically located, they now compete online as well. Investments online are expensive and uncertain, prompting some firms to partner with new entrants such as Amazon. Free from brick-and-mortar stores, Amazon, the dominant new entrant, has a highly scalable cost structure. And in many ways the online buying experience is superior to what customers saw in stores. Customers can hear samples of almost all tracks, selection is seemingly limitless (the long tail phenomenon—see this concept illuminated in Chapter 4 "Netflix in Two Acts: The Making of an E-commerce Giant and the Uncertain Future of Atoms to Bits"), and data is leveraged using collaborative filtering software to make product recommendations and assist in music discovery.For more on the long tail and collaborative filtering, see Chapter 4 "Netflix in Two Acts: The Making of an E-commerce Giant and the Uncertain Future of Atoms to Bits". Tough competition, but it gets worse because CD sales aren’t the only way to consume music. The process of buying a plastic disc now faces substitutes as digital music files become available on commercial music sites. Who needs the physical atoms of a CD filled with ones and zeros when you can buy the bits one song at a time? Or don’t buy anything and subscribe to a limitless library instead.

From a sound quality perspective, the substitute good of digital tracks purchased online is almost always inferior to their CD counterparts. To transfer songs quickly and hold more songs on a digital music player, tracks are encoded in a smaller file size than what you’d get on a CD, and this smaller file contains lower playback fidelity. But the additional tech-based market shock brought on by digital music players (particularly the iPod) has changed listening habits. The convenience of carrying thousands of songs trumps what most consider just a slight quality degradation. ITunes is now responsible for selling more music than any other firm, online or off. Apple can’t rest on its laurels, either. The constant disruption of tech-enabled substitute goods has created rivals like Spotify and Pandora that don’t sell music at all, yet have garnered tens of millions of users across desktop and mobile platforms. Most alarming to the industry is the other widely adopted substitute for CD purchases—theft. Illegal music “sharing” services abound, even after years of record industry crackdowns. And while exact figures on real losses from online piracy are in dispute, the music industry has seen album sales drop by 45 percent in less than a decade.K. Barnes, “Music Sales Boom, but Album Sales Fizzle for ’08,” USA Today, January 4, 2009. All this choice gives consumers (buyers) bargaining power. They demand cheaper prices and greater convenience. The bargaining power of suppliers—the music labels and artists—also increases. At the start of the Internet revolution, retailers could pressure labels to limit sales through competing channels. Now, with many of the major music retail chains in bankruptcy, labels have a freer hand to experiment, while bands large and small have new ways to reach fans, sometimes in ways that entirely bypass the traditional music labels.

While it can be useful to look at changes in one industry as a model for potential change in another, it’s important to realize that the changes that impact one industry do not necessarily impact other industries in the same way. For example, it is often suggested that the Internet increases bargaining power of buyers and lowers the bargaining power of suppliers. This suggestion is true for some industries like auto sales and jewelry where the products are commodities and the price transparencyThe degree to which complete information is available. of the Internet counteracts a previous information asymmetryA decision situation where one party has more or better information than its counterparty. where customers often didn’t know enough information about a product to bargain effectively. But it’s not true across the board.

In cases where network effects are strong or a seller’s goods are highly differentiated, the Internet can strengthen supplier bargaining power. The customer base of an antique dealer used to be limited by how many likely purchasers lived within driving distance of a store. Now with eBay, the dealer can take a rare good to a global audience and have a much larger customer base bid up the price. Switching costs also weaken buyer bargaining power. Wells Fargo has found that customers who use online bill pay (where switching costs are high) are 70 percent less likely to leave the bank than those who don’t, suggesting that these switching costs help cement customers to the company even when rivals offer more compelling rates or services.

Tech plays a significant role in shaping and reshaping these five forces, but it’s not the only significant force that can create an industry shock. Government deregulation or intervention, political shock, and social and demographic changes can all play a role in altering the competitive landscape. Because we live in an age of constant and relentless change, mangers need to continually visit strategic frameworks to consider any market-impacting shifts. Predicting the future is difficult, but ignoring change can be catastrophic.

Key Takeaways

- Industry competition and attractiveness can be described by considering the following five forces: (1) the intensity of rivalry among existing competitors, (2) the potential for new entrants to challenge incumbents, (3) the threat posed by substitute products or services, (4) the power of buyers, and (5) the power of suppliers.

- In markets where commodity products are sold, the Internet can increase buyer power by increasing price transparency.

- The more differentiated and valuable an offering, the more the Internet shifts bargaining power to sellers. Highly differentiated sellers that can advertise their products to a wider customer base can demand higher prices.

- A strategist must constantly refer to models that describe events impacting their industry, particularly as new technologies emerge.

Questions and Exercises

- What are Porter’s “five forces”?

- Use the five forces model to illustrate competition in the newspaper industry. Are some competitors better positioned to withstand this environment than others? Why or why not? What role do technology and resources for competitive advantage play in shaping industry competition?

- What is price transparency? What is information asymmetry? How does the Internet relate to these two concepts? How does the Internet shift bargaining power among the five forces?

- How has the rise of the Internet impacted each of the five forces for music retailers?

- In what ways is the online music buying experience superior to that of buying in stores?

- What is the substitute for music CDs? What is the comparative sound quality of the substitute? Why would a listener accept an inferior product?

- Based on Porter’s five forces, is this a good time to enter the retail music industry? Why or why not?

- What is the cost to the music industry of music theft? Cite your source.

- Discuss the concepts of price transparency and information asymmetry as they apply to the diamond industry as a result of the entry of BlueNile. Name another industry where the Internet has had a similar impact.

- Under what conditions can the Internet strengthen supplier bargaining power? Give an example.

- What is the effect of switching costs on buyer bargaining power? Give an example.

- How does the Internet impact bargaining power for providers of rare or highly differentiated goods? Why?