This is “The Battle Unfolds”, section 14.10 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.3). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.10 The Battle Unfolds

Learning Objectives

- Understand the challenges of maintaining growth as a business and industry mature.

- Recognize how the businesses of many firms in a variety of industries are beginning to converge.

- Critically evaluate the risks and challenges of businesses that Google, Microsoft, and other firms are entering.

- Appreciate the magnitude of this impending competition, and recognize the competitive forces that will help distinguish winners from losers.

Google has been growing like gangbusters, but the firm’s twin engines of revenue growth—ads served on search and through its ad networks—will inevitably mature. And it will likely be difficult for Google to find new growth markets that are as lucrative as these. Emerging advertising outlets such as social networks have lower click-through rates than conventional advertising, and Google has struggled to develop a presence in social media—trends suggesting that Google will have to work harder for less money.

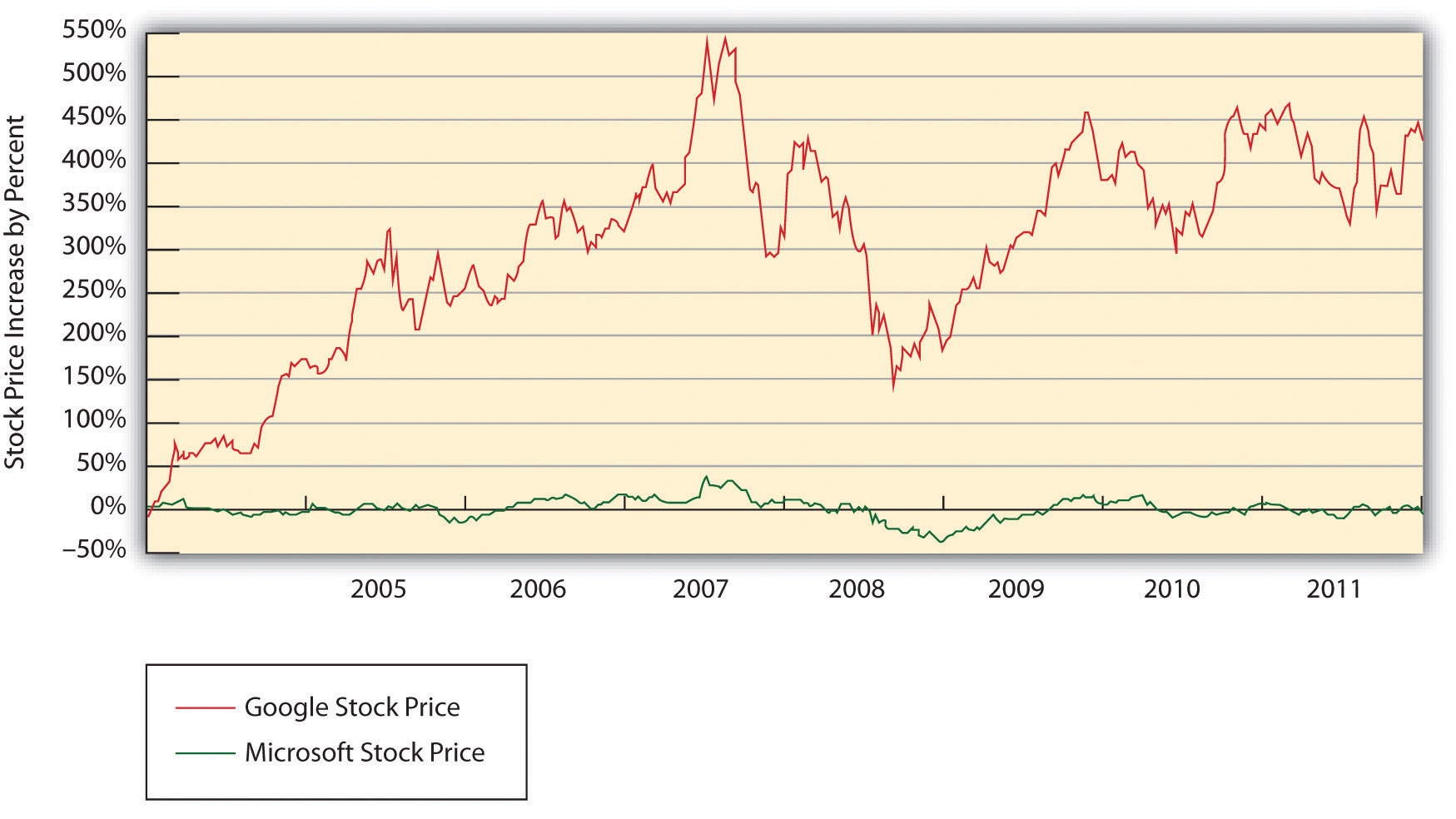

To understand what can happen when maturity hits, look at Microsoft. The House that Gates Built is more profitable than Google, and continues to dominate the incredibly lucrative markets served by Windows and Office. But these markets haven’t grown much for over a decade. In industrialized nations, most Windows and Office purchases come not from growth, but when existing users upgrade or buy new machines. And without substantial year-on-year growth, the stock price doesn’t move.

Figure 14.14 A Comparison of Stock Price Change—Google (GOOG) versus Microsoft (MSFT)

For big firms like Microsoft and Google, pushing stock price north requires not just new markets, but billion-dollar ones. Adding even $100 million in new revenues doesn’t do much for firms bringing in $62 billion and $29 billion a year, respectively. That’s why you see Microsoft swinging for the fences, investing in the uncertain but potentially gargantuan markets of video games, mobile phone software, cloud computing (see Chapter 10 "Software in Flux: Partly Cloudy and Sometimes Free"), music and video, and of course, search and everything else that fuels online ad revenue. Finding new billion-dollar markets is wonderful, but rare. Apple seems to have done it with the iPad. But trying to unseat a dominant leader possessing strategic resources can be ferociously expensive, with unclear prospects for success. Microsoft’s Bing group lost over $2 billion over just nine months, winning almost no share from Google despite the lavish spend.D. Goldman, “Microsoft Profits Soars 31% on Strong Office and Kinect Sales,” CNNMoney, April 28, 2011.

Search: Google Rules, but It Ain’t Over

PageRank is by no means the last word in search, and offerings from Google and its rivals continue to evolve. Google supplements PageRank results with news, photos, video, and other categorizations. Yahoo! is continually refining its search algorithms and presentation. And Microsoft’s third entry into the search market, the “decision engine” Bing, sports nifty tweaks for specific kinds of queries. Restaurant searches in Bing are bundled with ratings stars, product searches show up with reviews and price comparisons, and airline flight searches not only list flight schedules and fares, but also a projection on whether those fares are likely go up or down. Bing also comes with a one-hundred-million-dollar marketing budget, showing that Microsoft is serious about search. And in the weeks following Bing’s mid-2009 introduction, the search engine did deliver Microsoft’s first substantive search engine market share gain in years.

New tools like the Wolfram Alpha “knowledge engine” (and to a lesser extent, Google’s experimental Google Squared service) move beyond Web page rankings and instead aggregate data for comparison, formatting findings in tables and graphs. Web sites are also starting to wrap data in invisible tags that can be recognized by search engines, analysis tools, and other services. If a search engine can tell that a number on a restaurant’s Web site is, for example, either a street address, an average entrée price, or the seating capacity, it will be much easier for computer programs to accurately categorize, compare, and present this information. This is what geeks are talking about when they refer to the semantic WebSites that wrap data in invisible tags that can be recognized by search engines, analysis tools, and other services to make it easier for computer programs to accurately categorize, compare, and present this information..

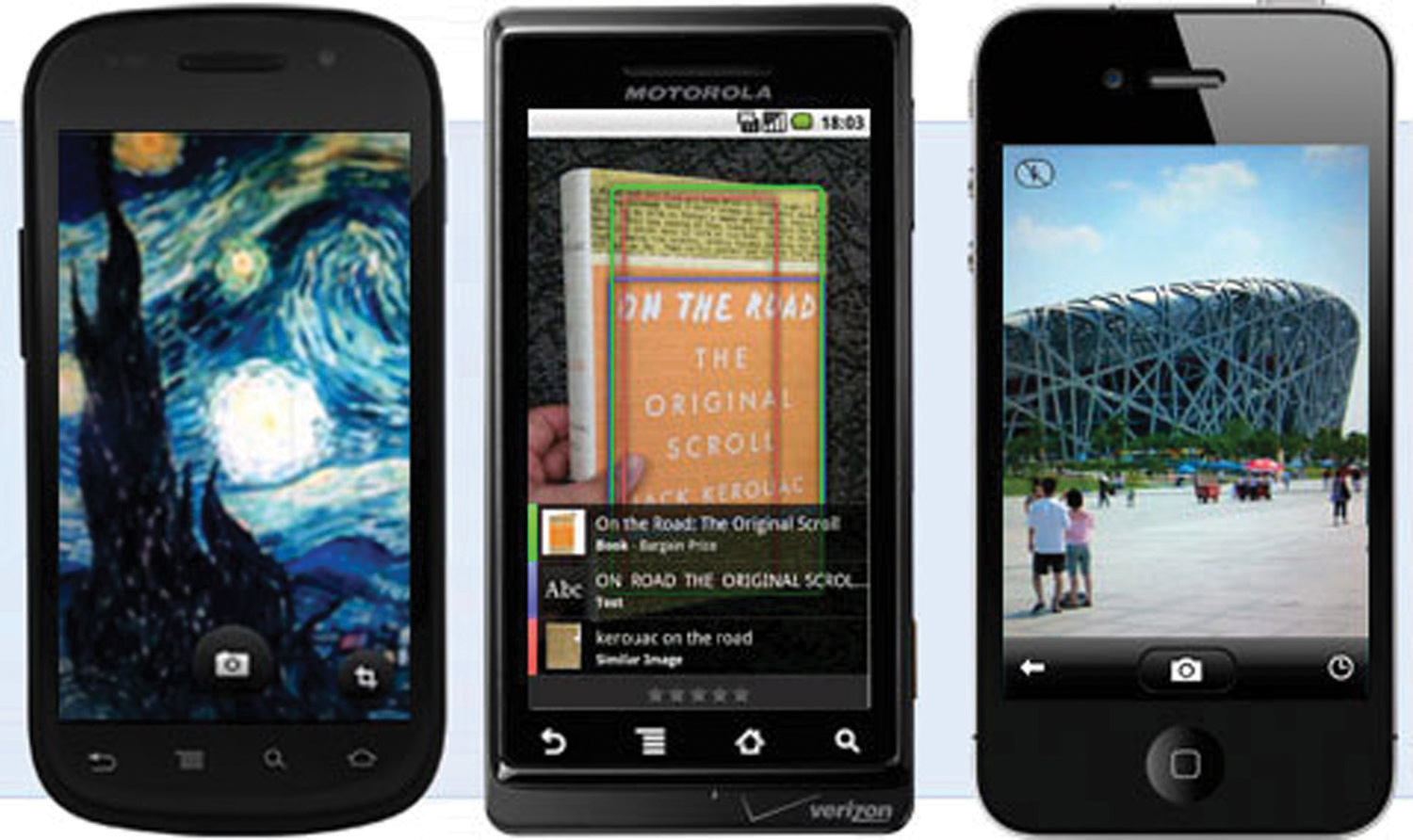

Figure 14.15 Google Goggles returns search results by photographing objects. It can even translate foreign language text.

Source: Google.

And who says you need to use words to conduct a search? Google Goggles uses the camera in your mobile phone to “enter” search criteria. Snap a picture of a landmark, book, or piece of artwork, for example, and Google will use that image to retrieve search results. The product can even return translations of foreign text. All signs point to more innovation, more competition, and an increasingly more useful Internet!

Both Google and Microsoft are on a collision course. But there’s also an impressive roster of additional firms circling this space, each with the potential to be competitors, collaborators, merger partners, or all of the above. While wounded and shrinking, Yahoo! is still a powerhouse, ranking ahead of Google in some overall traffic statistics. Google’s competition with Apple in the mobile phone business prompted Google’s then CEO Eric Schmidt to resign from Apple’s board of directors. Meanwhile, Google’s three-quarters-of-a-billion-dollar purchase of the leading mobile advertiser AdMob was quickly followed by Apple snapping up number two mobile ad firm Quattro Wireless for $275 million. Add in Amazon, Facebook, eBay, Twitter, Salesforce.com, Netflix, the video game industry, telecom and mobile carriers, cable firms, and the major media companies and the next few years have the makings of a big, brutal fight.

Strategic Issues

As outlined earlier, Google enjoys major scale advantages in search, and network effects in advertising. The firm’s dominance helps grow a data asset that can be used in service improvement, all while its expertise in core markets continues to grow over time. But the strength of Google’s other competitive resources is less clear.

Within Google’s ad network, there are switching costs for advertisers and for content providers. Google partners have set up accounts and are familiar with the firm’s tools and analytics. Content providers would also need to modify Web sites to replace AdSense or DoubleClick ads with rivals. But choosing Google doesn’t cut out the competition. Many advertisers and content providers participate in multiple ad networks, making it easier to shift business from one firm to another. This likely means that Google will have to keep advertisers by offering superior value rather than relying on lock-in.

Another vulnerability may exist with search consumers. While Google’s brand is strong, switching costs for search users are incredibly low. Move from Google.com to Bing.com and you actually save two letters of typing!

Still, there are no signs that Google’s search leadership is in jeopardy. So far users have been creatures of habit; no rival has offered technology compelling enough to woo away the Googling masses. Defeating Google with some sort of technical advantage will be difficult since Web-based innovation can often be quickly imitated. Google now rolls out over 550 tweaks to its search algorithm annually, with many features mimicking or outdoing innovations from rivals.S. Levy, “Inside the Box,” Wired, March 2010.

The Google Toolbar helps reinforce search habits among those who have it installed, and Google has paid the Mozilla foundation (the folks behind the Firefox browser) upwards of $66 million a year to serve as its default search option for the open source browser.S. Shankland, “Thanks, Google: Mozilla Revenue Hits $75 Million,” CNET, November 19, 2008. But Google’s track record in expanding reach through distribution deals is mixed. The firm spent nearly $1 billion to run ads on MySpace, later stating the deal had not been as lucrative as it had hoped (see Chapter 8 "Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph"). The firm has also spent nearly $1 billion to have Dell preinstall its computers with the Google browser toolbar and Google desktop search products. But Microsoft later inked deals that displaced Google on Dell machines, and it also edged Google out in a five-year search contract with Verizon Wireless.N. Wingfield, “Microsoft Wins Key Search Deals,” Wall Street Journal, January 8, 2009.

How Big Is Too Big?

Microsoft could benefit from embedding its Bing search engine into its most popular products (imagine putting Bing in the right-mouseclick menu alongside cut, copy, and paste). But with Internet Explorer market share above 65 percent, Office above 80 percent, and Windows at roughly 90 percent,Data source: http://marketshare.hitslink.com; and E. Montalbano, “Forrester: Microsoft Office in No Danger from Competitors,” InfoWorld, June 4, 2009. this seems unlikely.

European antitrust officials have already taken action against Redmond’s bundling Windows Media Player and Internet Explorer with Windows. Add in a less favorable antitrust climate in the United States, and tying any of these products to Bing is almost certainly out of bounds. What’s not clear is whether regulators would allow Bing to be bundled with less dominant Microsoft offerings, such as mobile phone software, Xbox, and MSN.

But increasingly, Google is also an antitrust target. Microsoft has itself raised antitrust concerns against Google, unsuccessfully lobbying both U.S. and European authorities to block the firm’s acquisition of DoubleClick.A. Broach, “On Capitol Hill, Google and Microsoft Spar over DoubleClick,” CNET, September 27, 2007; and D. Kawamoto and A. Broach, “EU Extends Review of Google-DoubleClick Merger,” CNET, November 13, 2007. Google was forced to abandon a search advertising partnership with Yahoo! after the Justice Department indicated its intention to block the agreement (Yahoo! and Microsoft have since inked a deal to share search technology and ad sales). The Justice Department is also investigating a Google settlement with the Authors’ Guild, a deal in which critics have suggested that Google scored a near monopoly on certain book scanning, searching, and data serving rights.S. Wildstrom, “Google Book Search and the Dog in the Manger,” BusinessWeek, April 18, 2009. And yet another probe investigated whether Google colluded with Apple, Yahoo! and other firms to limit efforts to hire away top talent.E. Buskirk, “Antitrust Probe to Review Hiring Practices at Apple, Google, Yahoo: Report,” Wired News, June 3, 2009.

Of course, being big isn’t enough to violate U.S. antitrust law. Harvard Law’s Andrew Gavil says, “You’ve got to be big, and you have to be bad. You have to be both.”S. Lohr and M. Helft, “New Mood in Antitrust May Target Google,” New York Times, May 18, 2009. This may be a difficult case to make against a firm that has a history of being a relentless supporter of open computing standards. And as mentioned earlier, there is little forcing users to stick with Google—the firm must continue to win this market on its own merits. Some suggest regulators may see Google’s search dominance as an unfair advantage in promoting its own properties such as YouTube, Google Maps, Google-owned Zagat, and Google+ over those offered by rivals.F. Vogelstein, “Why Is Obama’s Top Antitrust Cop Gunning for Google?” Wired, July 20, 2009. The toolbar that appears across the top of most Google websites also provides preferred access to Google properties but not rivals—some may argue that these advantages are not unlike Microsoft’s use of Windows to promote Media Player and Internet Explorer. While Google may escape all of these investigations, increased antitrust scrutiny is a downside that comes along with the advantages of market-dominating scale.

More Ads, More Places, More Formats

Google has been a champion of increased Internet access. But altruism aside, more net access also means a greater likelihood of ad revenue.

Google’s effort to catalyze Internet use worldwide comes through on multiple fronts. In the United States, Google has supported (with varying degrees of success) efforts to offer free Wi-Fi in San Francisco and Mountain View. Google announced it would offer high-speed, fiber-optic net access to homes in select U.S. cities, with Kansas City, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri, chosen for the first rollouts.L. Horsley, “KC Council Unanimously Approves Deal with Google,” Kansas City Star, May 19, 2011. The experimental network would offer competitively priced Internet access of up to 1GB per second—that’s a speed some one hundred times faster than many Americans have access to today. The networks are meant to be open to other service providers and Google hopes to learn and share insights on how to build high-speed networks more efficiently. Google will also be watching to see how access to ultrahigh-speed networks impacts user behavior and fuels innovation. Globally, Google is also a major backer (along with Liberty Global and HSBC) of the O3b satellite network. O3b stands for “the other three billion” of the world’s population who currently lack Internet access. O3b plans to have multiple satellites circling the globe, blanketing underserved regions with low latencyLow delay. (low delay), high-speed Internet access.O. Malik, “Google Invests in Satellite Broadband Startup,” GigaOM, September 9, 2008. With Moore’s Law dropping computing costs as world income levels rise, Google hopes to empower the currently disenfranchised masses to start surfing. Good for global economies, good for living standards, and good for Google.

Google has also successfully lobbied the U.S. government to force wireless telecom carriers to be more open, dismantling what are known in the industry as walled gardensA closed network or single set of services controlled by one dominant firm. Term is often applied to mobile carriers that act as gatekeepers, screening out hardware providers and software services from their networks.. Before Google’s lobbying efforts, mobile carriers could act as gatekeepers, screening out hardware providers and software services from their networks. Now, paying customers of carriers that operate over the recently allocated U.S. wireless spectrum will have access to a choice of hardware and less restrictive access to Web sites and services. And Google hopes this expands its ability to compete without obstruction.

Another way Google can lower the cost of surfing is by giving mobile phone software away for free. That’s the thinking behind the firm’s Android offering. With Android, Google provides mobile phone vendors with a Linux-based operating system, supporting tools, standards, and an application marketplace akin to Apple’s App Store. Android itself isn’t ad-supported—there aren’t Google ads embedded in the OS. But the hope is that if handset manufacturers don’t have to write their own software, the cost of wireless mobile devices will go down. And cheaper devices mean that more users will have access to the mobile Internet, adding more ad-serving opportunities for Google and its partner sites. Google already controls 97 percent of fast-growing paid search on mobile devices.“Google Manages 97 Percent of Paid Mobile Search, 40 Pct of Google Maps Usage Is Mobile,” Mobile Marketing Watch, March 14, 2011. One analyst estimates that Android should bring in $10 per handset in search advertising by 2012, goosing advertising revenue by about $1.3 billion.G. Sterling, “Google Will Make $10 Per Android User in 2012: Report,” SearchEngineLand, February 9, 2011. If this prediction holds, this would mean Android has helped Google deliver that rare, new billion-dollar opportunity that so many large firms seek.

Developers are now leveraging tailored versions of Android on a wide range of devices, including e-book readers, tablets, televisions, set-top boxes, robots, and automobiles. Google has dabbled in selling ads for television (as well as radio and print), and there may be considerable potential in bringing variants of ad targeting technology, search, and a host of other services across these devices. Google also offers a platform for creating what the firm calls “Chromebooks”—a direct challenge to Windows in the netbook PC market. Powered by a combination of open source Linux and Google’s open source Chrome browser, the Chrome OS is specifically designed to provide a lightweight but consistent user interface for applications that otherwise live in the cloud, preferably residing on Google’s server farms (see Chapter 10 "Software in Flux: Partly Cloudy and Sometimes Free").

Motorola Mobility

Google’s massive, multi-billion dollar cash horde is also allowing the firm to go on a buying spree—gobbling up 57 firms in just the first three quarters of 2011.E. Rusli, “For Google, A New High in Deal-Making,” The New York Times, Oct. 27, 2011. Google’s biggest deal to date was the purchase of Motorola Mobility. This makes Google a mobile phone handset manufacturer. While Google CEO Larry Page has said that Android will remain open and that Motorola Mobility will be run as a separate business,J. Cox, “CEO Larry Page Blogs On Why Google’s Buying Motorola Mobility,” ComputerWorld, Aug. 15, 2011. Google’s entry into the low-margin handset business may also alienate other potential Android partners.

The deal also gives Google ownership of the leading set-top box manufacturer, with products that sit in roughly 65 percent of US homes with cable TV sets.T. Spangler, “Does Google Actually Have a Plan for Motorola's Cable Business?”, Multichannel News, Aug. 15, 2011. While Google’s plans for the set-top box business are unclear, possibilities could include opening up new markets for existing Internet advertising, and creating new businesses serving targeted video ads. Adding Google TV software into cable set-top boxes might also bring a Google app store to your television. Executing on these possibilities will be challenging, as most cable firms (the customers for Motorola’s set-top boxes) have fiercely defended their walled gardens from running apps from Netflix or other potentially threatening services.R. Lawler and R. Kim, “With Motorola, Google TV Just Got a Huge Shot in the Arm,” GigaOm, Aug. 15, 2011. But Google may find neutral ground for a subset of services that can keep cable providers and television networks happy by sharing in new revenue opportunities.

The $12.5 billion for Motorola also brings in 17,000 patents—a potentially vital resource as big firms sue one another to protect their markets. Apple has leveraged its patents to shut down Samsung tablet sales in Germany and Australia,M. Ricknäs, “Motorola Gets Injunction Against Apple in Germany,” PC World, Nov. 7, 2011. and Google fears that Cupertino may come knocking, claiming Android is a copy of the heavily patented iPhone. Motorola’s patents give Google an intellectual property counterpunch. (A brief side note, IP means Internet protocol, but is also often used to refer to intellectual property. When see the term IP, be sure to consider the context so you know which IP is being talked about).

YouTube

It’s tough to imagine any peer-produced video site displacing YouTube. Users go to YouTube because there’s more content, while amateur content providers go there seeking more users (classic two-sided network effects). This critical advantage was the main reason why, in 2006, Google paid $1.65 billion for what was then just a twenty-month-old start-up. But Google isn’t content to let YouTube be simply the home for online amateur hour. The site now “rents” hundreds of TV shows and movies at prices raning from $.99 to $3.99 It’s also been offering seed grants of several million dollars to producers of original content for YouTube.M. Learmonth, “YouTube's Premium-Content Strategy Starts to Take Shape,” AdAge, March 14, 2011. And it even poached a senior Netflix executive to help grow the premium content business.D. Chmielewski, “YouTube counting on former Netflix exec to help it turn a profit.” Los Angeles Times. May 31, 2011.

YouTube’s popularity comes at a price. Even with falling bandwidth and storage costs, at forty-eight hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute, the cost to store and serve this content is cripplingly large.J. Roettgers, “YouTube Users Upload 48 Hours of Video Every Minute,” GigaOm, May 25, 2011. Credit Suisse estimates that in 2009, YouTube brought in roughly $240 million in ad revenue, pitted against $711 million in operating expenses. That’s a shortfall of more than $470 million. Analysts estimate that for YouTube to break even, it would need to achieve an ad CPM of $9.48 on each of the roughly seventy-five billion streams it’ll serve up this year. A tough task. For comparison, Hulu (a site that specializes in offering ad-supported streams of television shows and movies) earns CPM rates of thirty dollars and shares about 70 percent of this with copyright holders. Most user-generated content sports CPM rates south of a buck.B. Wayne, “YouTube Is Doomed,” Silicon Alley Insider, April 9, 2009. Some differ with the Credit Suisse report—RampRate pegged the losses at $174 million. In fact, it may be in Google’s interest to allow others to think of YouTube as more of a money pit than it really is. That perception might keep rivals away longer, allowing the firm to solidify its dominant position, while getting the revenue model right. Even as a public company, Google can keep mum about YouTube specifics. Says the firm’s CFO, “We know our cost position, but nobody else does.”“How Can YouTube Survive?” Independent, July 7, 2009.

The explosion of video uploading is also adding to costs as more cell phones become Net-equipped video cameras. YouTube’s mobile uploads were up 400 percent in just the first week following the launch of the first video-capturing iPhone.J. Kincaid, “YouTube Mobile Uploads Up 400% Since iPhone 3GS Launch,” TechCrunch, June 25, 2009. Viewing will also skyrocket as mobile devices and television sets ship with YouTube access (the YouTube division is now home to the Google TV consumer electronics platform), adding to revenue potential. The firm is still experimenting with ad models—these include traditional banner and text ads, plus ads transparently layered across the bottom 20 percent of the screen, preroll commercials that appear before the selected video, and more. Google has both the money and time to invest in nurturing this market, and it continues to be hesitant in saturating the media with ads that may annoy users and constrain adoption.

Google Wallet

Google Wallet is another example of how the search giant is looking to deliver value through mobile devices. Announced in the spring of 2011, Google Wallet allows phones to replace much of the “stuff” inside your wallet. It can be used to pay for goods, store gift cards, collect and redeem coupons and special offers, and manage loyalty programs. To use the service, users simply wave phones at an NFCNear field communication; a short-range, wireless communication standard. NFC is being used to support contactless payment and transactions over NFC-equipped mobile devices. (near field communication)-equipped payment terminal (with transaction confirmed and secured by typing in a PIN). Fifteen retailers (including Macy’s, Subway, Walgreens, Toys “R” Us, Peet’s Coffee and Tea, and Footlocker) were announced as payment-accepting partners, and Wallet has the capability to work with some 300,000 retail registers that are already using MasterCard’s PayPass contactless payment terminals.D. Melanson, “Google Wallet Mobile Payment Service, Google Offers Announced,” Engadget, May 26, 2011; E. Hamburger, “Google Introduces Wallet, Google Wallet Works at Over 300,000 MasterCard PayPass Merchants,” BusinessInsider, May 26, 2011. Phones will have to be equipped with an NFC chip, and only one model from one carrier was available at announcement, although a limited version of Wallet will be available by using an NFC sticker that can be attached to the back of non-NFC mobile devices. Google also envisions billboards and storefronts that can communicate with Wallet and distribute offers, Web links, and more—just wave your phone at a sign to get a deal. The product is less about becoming the “Bank of Google”—Wallet links to existing credit cards (although Google offers a prepaid card, too), and at rollout Google said there would be no payment fees for the service. But Google hopes payment and other services will be a way to promote new revenue channels, such as growing its Google Offers coupon service, allowing it to compete with daily deal sites like Groupon and LivingSocial.H. Tsukayama, “Google Wallet: Search Giant Introduces Automatic Cellphone Payment System,” The Washington Past, May 26, 2011.. Google could sell advertisers couponing services distributed via search, online ads, NFC-equipped signs, and geolocation; have the deals and promotions delivered to a Google Wallet account; and allow deals to be quickly redeemed via NFC swipe at a retailer. Could this grow to be a billion-dollar market, too? Emerging technologies like NFC are sure to attract competitors and innovation.

Figure 14.16 Google Wallet

Source: Google.

Social: Google+

Google’s success in social media has been mixed. Its two biggest successes—YouTube and Blogger—were both acquired from other firms. Internally-developed Orkut has for years ranked as the top social network in Brazil but has limited success in only a few other nations; and Google-hatched Buzz and Wave were both dismal failures. But with Google+ the firm may have finally created a service with staying power.

Google+ rolled out in summer 2011 as an integrated collection of social products associated with a user’s Google profile. Stream is a newsfeed. Sparks is a recommendation engine. Hangouts is a video chat service that can support groups, and enables screen sharing and group document editing. Huddle offers group texting. Circles helps manage sharing contacts (so you can share a given item with just ‘friends,’ ‘business contacts,’ or any other sharing circles you want to create). And Photos is an image sharing service that leverages the firm’s Picasa offering. This allows Google to offer up a set of features similar to those found in Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Skype, and Group.me. And initial Google+ features were just a start—the firm has been hard at work adding Games, Questions, services that allow businesses to get in on the socializing, and more.

Learning from earlier failure, Google+ got a lot of things right. The interface design was praised (Andy Hertzfeld, a member of the original Macintosh design team, was behind design efforts), and the new features were tightly integrated with other Google products. A toolbar that runs on top of most Google services means that Google+ is just a click away. Circles were easily built from Gmail contacts, but offered a degree of sharing control, customization, and privacy that distinguished it as a solid alternative to Facebook and other offerings. Despite being launched only in invitation-only beta, Google+ attracted some 10 million members in just its first two weeks, making it the fastest growing social network of all time.D. Goldman, “Google+ Grows to 10 Million Users,” Fortune, July 14, 2011. M. Schuster, M. Schuster, “Report: Google+ the Fastest-Growing Social Network Ever,” Minyanville, July 12, 2011. While growing faster than Facebook and Twitter did at this stage, the Google+ user base is still very far behind both. If Google+ is a hit, the firm could gain an opportunity to serve more ads, grow additional revenue lines (e.g. a game currency to rival Facebook Credits), and gain additional data and insight that can be used to help in search, content recommendations, and ad targeting. Competing in winner-take-most markets where network effects dominate will be tough, but Google brings a number of assets to the table and seems committed to growing the effort. CEO Larry Page has event stated Google will tie employee bonuses to the success of the firm’s social efforts.

What’s Google Up To?

With all this innovation, it’s tough to stay current with Google’s cutting edge product portfolio. But the company does offer “beta” releases of some projects, and invites the public to try out and comment on its many experiments. To see a current list of many of the firm’s offerings, check out http://www.google.com/options.

Experimentation and innovation are deeply ingrained in Google’s tech-centric culture, and this can produce both hits and misses. While Google introduces scores of products each year,M. Shiels, “Google Unveils ‘Smarter Search,’” BBC News, May 13, 2009.it has also cancelled several along the way, including Jaiku (which couldn’t beat Twitter), Google Video (which was superseded by the YouTube acquisition), Google Buzz (a social networking flop), Google Wave (despite its splashy launch), and a bunch more you’ve likely not heard of, like Dodgeball, Notebook, Catalog Search, and Mashup Editor.R. Needleman, “Google Killing Jaiku, Dodgeball, Notebook, Other Projects,” CNET, January 14, 2009. But the firm’s relentless commitment to developing new products and services, coupled with wildly profitable core businesses, allows Google to survive the flops and push the edge of what’s possible. The firm’s secretive lab, Google X, is working on all sorts of gee-whiz offerings, including self-driving cars, space elevators, and refrigerators that can order your groceries when they run low.C. C. Miller and N. Bolton, “Google’s Lab of Wildest Dreams,” The New York Times, Nov. 13, 2011.

Apps and Innovation

Google’s “apps” are mostly Web-based software-as-a-service offerings. Apps include an Office-style suite that sports a word processor, presentation tool, and spreadsheet, all served through a browser. While initially clunky, the products are constantly being refined. The spreadsheet product, for example, has been seeing new releases every two weeks, with features such as graphing and pivot tables inching it closer in capabilities to desktop alternatives.D. Girouard, “Google Inc. Presentation” (Bank of America and Merrill Lynch 2009 Technology Conference, New York, June 4, 2009). And new browser standards, such as HTML 5, will make it even easier for what lives in the browser to mimic what you’re currently using on your desktop, even allowing apps to be used offline when net access isn’t available. That’ll be critical as long as Internet access is less reliable than your hard drive, but online collaboration is where these products can really excel (no pun intended). Most Google apps allow not only group viewing, but also collaborative editing, common storage, and version control. And it seems Google isn’t stopping at Office files, video, and photos—Google’s cloud will hold your music, too. Google’s Music service allows you to not only buy music, but also upload thousands of the tracks that you already own to what some have called a sort of “locker in the sky.” Users can stream the tracks over the Internet, sync frequently played songs and albums for offline play, and even share tracks with friends via Google+ (friends usually get one full listen for free).D. Murph, “Google Music Beta Walkthrough: What It Is and How It Works (Video),” Engadget, May 11, 2011.

Unknown is how much money Google will make off all of this. Consumers and small businesses have free access to these products, with usage for up to fifty users funded by in-app ads. But is there much of a market serving ads to people working on spreadsheets? Enterprises can gain additional, ad-free licenses for a fee. While users have been reluctant to give up Microsoft Office, many have individually migrated to Google’s Web-based e-mail and calendar tools. Google’s enterprise apps group will now do the same thing for organizations, acting as a sort of outsourcer by running e-mail, calendar, and other services for a firm and all while handling upgrades, spam screening, virus protection, backup, and other administrative burdens. Virgin America, Jaguar, National Geographic, and Genentech are among the Google partners that have signed on to make the firm’s app offerings available to thousands.

And of course, Microsoft won’t let Google take this market without a fight. Microsoft has experimented with offering a simplified, free, ad-supported, Web-based, online options for Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and OneNote; Office 365 offers more robust online tools, ad free, for a low monthly subscription cost; and Microsoft can also migrate an organization’s applications like e-mail and calendaring off corporate computers and onto Microsoft’s server farms.

Google’s Global Reach and the Censorship Challenge

In the spring of 2010, Google clashed publicly with the government of China, a nation that many consider to be the world’s most potentially lucrative market. For the previous four years and at the request of the Chinese government, Google had censored results returned from the firm’s google.cn domain (e.g., an image search on the term “Tiananmen” showed kite flying on google.cn, but protestors confronting tanks on google.com). However, when reports surfaced of Chinese involvement in hacking attempts against Google and at least twenty other U.S. companies and human rights dissidents, the firm began routing google.cn traffic outside the country. The days that followed saw access to a variety of Google services blocked within China, restricted by what many call the government’s “Great Firewall of China.”

Speaking for Google, the firm’s deputy counsel Nicole Wong states, “We are fundamentally guided by the belief that more information for our users is ultimately better.” But even outside of China, Google continues to be challenged by its interest in providing unfettered access to information on one hand, and the radically divergent laws, regulations, and cultural expectations of host nations on the other. Google has been prompted to block access to its services at some point in at least twenty-five of one hundred countries the firm operates in.

The kind of restriction varies widely. French, German, and Polish law requires Google to prohibit access to Nazi content. Turkish law requires Google to block access to material critical of the nation’s founder. Access in Thailand is similarly blocked from content mocking that nation’s king. In India, Google has been prompted to edit forums or remove comments flagged by the government as violating restrictions against speech that threatens public order or is otherwise considered indecent or immoral. At the extreme end of the spectrum, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, have aggressively moved to restrict access to wide swaths of Internet content.

Google usually waits for governments to notify it that offensive content must be blocked. This moves the firm from actively to reactively censoring access. Still, this doesn’t isolate the company from legal issues. Italian courts went after YouTube executives after a video showing local teenagers tormenting an autistic child remained online long enough to garner thousands of views.

In the United States, Google’s organic results often reveal content that would widely be viewed as offensive. In the most extreme cases, the firm has run ads alongside these results with the text, “Offensive Search Results: We’re disturbed about these results as well. Please read our note here.”

Other Internet providers have come under similar scrutiny, and technology managers will continue to confront similar ethically charged issues as they consider whether to operate in new markets. But Google’s dominant position puts it at the center of censorship concerns. The threat is ultimately that the world’s chief information gateway might also become “the Web’s main muzzle.”

It’s not until considered in its entirety that one gets a sense of what Google has the potential to achieve. It’s possible that increasing numbers of users worldwide will adopt light, cheap netbooks and other devices powered by free Google software (Android, Google’s Chrome browser and Chrome OS). Productivity apps, e-mail, calendaring, and collaboration tools will all exist in the cloud, accessible through any browser, with files stored on Google’s servers in a way that minimizes hard drive needs. Google will entertain you, help you find the information you need, help you shop, handle payment, and more. And the firms you engage online may increasingly turn to Google to replace their existing hardware and software infrastructure with corporate computing platforms like Google Apps Engine (see Chapter 10 "Software in Flux: Partly Cloudy and Sometimes Free"). All of this would be based on open standards, but switching costs, scale, and increasing returns from expertise across these efforts could yield enormous advantages.

Studying Google allowed us to learn about search and the infrastructure that powers this critical technology. We’ve studied the business of ads, covering search advertising, ad networks, and ad targeting in a way that blends strategic and technology issues. And we’ve covered the ethical, legal, growth, and competitive challenges that Google and its rivals face. Studying Google in this context should not only help you understand what’s happening today, it should also help you develop critical thinking skills for assessing the opportunities and threats that will emerge across industries as technologies continue to evolve.

Key Takeaways

- For over a decade, Google’s business has been growing rapidly, but that business is maturing.

- Slower growth will put pressure on the firm’s stock price, so a firm Google’s size will need to pursue very large, risky, new markets—markets that are also attractive to well-financed rivals, smaller partners, and entrepreneurs.

- Rivals continue to innovate in search. Competing with technology is extremely difficult since it is often easy for a firm to mimic the innovations of a pioneer with a substitute offering. Microsoft, with profits to invest in infrastructure, advertising, and technology, may pose Google’s most significant, conventional threat.

- Although Microsoft has many distribution channels (Windows, Internet Explorer, Office) for its search and other services, European and U.S. regulators will likely continue to prevent the firm from aggressive product and service bundling.

- Google is investing heavily in methods that promote wider Internet access. These include offering free software to device manufacturers and several telecommunications and lobbying initiatives meant to lower the cost of getting online. The firm hopes that more users spending more time online will allow it to generate more revenue through ads and perhaps other services.

- Google Wallet uses NFC communications to allow mobile phones to make credit and debit card payments, manage loyalty programs, redeem coupons, and more. Payments are linked to existing credit cards. Google will not charge for transaction fees but plans to use Wallet as a way to sell other services such as those offered by its Google Offers coupon and deal program.

- YouTube demonstrates how a firm can create a large and vastly influential business in a short period of time but also that businesses that host and serve large files of end-user content can be costly.

- Google, Microsoft, and smaller rivals are also migrating applications to the Web, allowing Office-style software to execute within a browser, with portions of this computing experience and storage happening off a user’s computer, “in the cloud” of the Internet. Revenue models for this business are also uncertain.

- With scale and influence comes increased governmental scrutiny. Google has increasingly become a target of antitrust regulators. The extent of this threat is unclear. Google’s extreme influence is clear. However, the firm’s software is based on open standards; competitors have a choice in ad networks, search engines, and other services; switching costs are relatively low; users and advertisers aren’t locked into exclusive contracts for the firm’s key products and services; and there is little evidence of deliberate, predatory pricing or other “red-flag” activity that usually brings government regulation.

Questions and Exercises

- Perform identical queries on both Google and on rival search engines. Try different categories (research for school projects, health, business, sports, entertainment, local information). Which sites do you think give you the better results? Why? Would any of these results cause you to switch to one search engine versus the other?

- Investigate new services that attempt to extend the possibilities for leveraging online content. Visit Bing, Google Squared, Wolfram Alpha, and any other such efforts that intrigue you. Assume the role of a manager and use these engines to uncover useful information. Assume your role as a student and see if these tools provide valuable information for this or other classes. Are you likely to use these tools in the future? Why or why not? Under what circumstances are they useful and when do they fall short?

- Assume the role of an industry analyst: Consider the variety of firms mentioned in this section that may become competitors or partners. Create a chart listing your thoughts on which firms are likely to collaborate and work together and which firms are likely to compete. What are the advantages or risks in these collaborations for the partners involved? Do you think any of these firms are “acquisition bait?” Defend your predictions and be prepared to discuss them with your class.

- Assume the role of an IT manager: To the extent that you can, evaluate online application offerings by Google, Microsoft, and rivals. In your opinion, are these efforts ready for prime time? Why or why not? Would you recommend that a firm choose these applications? Are there particular firms or users that would find these alternatives particularly appealing? Would you ever completely replace desktop offerings with online ones? Why or why not?

- Does it make sense for organizations to move their e-mail and calendaring services off their own machines and pay Google, Microsoft, or someone else to run them? Why or why not?

- What are Chrome, the Chrome OS, and Android? Are these software products successful in their respective categories? Investigate the state of the market for products that leverage any of these software offerings. Would you say that they are successful? Why or why not? What do you think the outlook is for Chrome, the Chrome OS, and Android? As an IT manager, would you recommend products based on this software? As an investor, do you think it continues to make sense for Google to develop these efforts? Why or why not?

- What will it take for Google Wallet to be successful? What challenges must the effort overcome?

- Research the current state of Google Wallet’s competitors. What competing efforts exist? Which firms are best positioned to dominate this market? How large could this market become?

- Google’s unofficial motto is “Don’t be evil.” But sometimes it’s challenging for managers to tell what path is “most right” or “least wrong.” Google operates in countries that require the firm to screen and censor results. Short term, this is clearly a limitation on freedom of speech. But long-term, access to the Internet could catalyze economic development and spread information in a way that leads to more democratization. Investigate and consider both of these arguments and be prepared to argue the case either for limiting work in speech-limiting countries or working within them as a potential agent of change. What other pressures is a publicly traded firm under to choose one path or the other? Which path would you choose and why?