This is “Understanding Search”, section 14.2 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.3). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.2 Understanding Search

Learning Objectives

- Understand the mechanics of search, including how Google indexes the Web and ranks its organic search results.

- Examine the infrastructure that powers Google and how its scale and complexity offer key competitive advantages.

Before diving into how the firm makes money, let’s first understand how Google’s core service, search, works.

Perform a search (or querySearch.) on Google or another search engine, and the results you’ll see are referred to by industry professionals as organic or natural searchSearch engine results returned and ranked according to relevance.. Search engines use different algorithms for determining the order of organic search results, but at Google the method is called PageRankAlgorithm developed by Google cofounder Larry Page to rank Web sites. (a bit of a play on words, it ranks Web pages, and was initially developed by Google cofounder Larry Page). Google does not accept money for placement of links in organic search results. Instead, PageRank results are a kind of popularity contest. Web pages that have more pages linking to them are ranked higher.

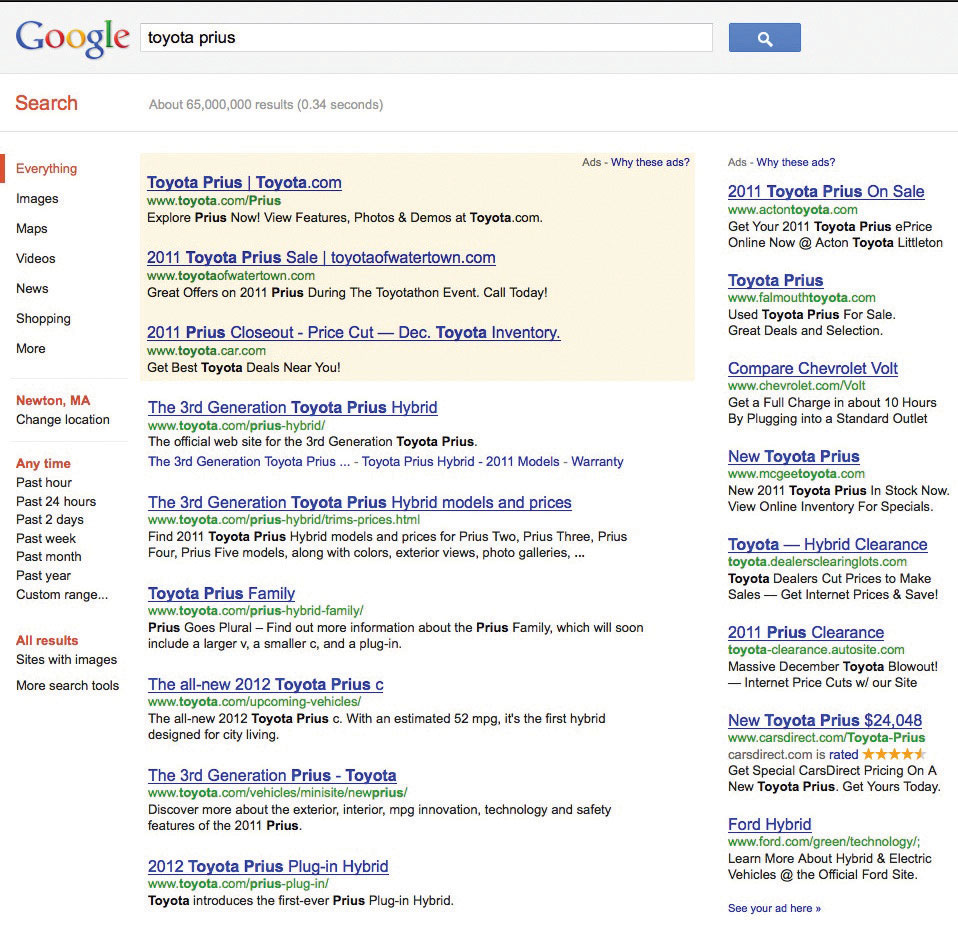

Figure 14.4

The query for “Toyota Prius” triggers organic search results, flanked top and right by advertisements.

The process of improving a page’s organic search results is often referred to as search engine optimization (SEO)The process of improving a page’s organic search results.. SEO has become a critical function for many marketing organizations since if a firm’s pages aren’t near the top of search results, customers may never discover its site.

Google is a bit vague about the specifics of precisely how PageRank has been refined, in part because many have tried to game the system. In addition to in-bound links, Google’s organic search results also consider some two hundred other signals, and the firm’s search quality team is relentlessly analyzing user behavior for clues on how to tweak the system to improve accuracy.S. Levy, “Inside the Box,” Wired, March 2010. The less scrupulous have tried creating a series of bogus Web sites, all linking back to the pages they’re trying to promote (this is called link fraudAlso called “spamdexing” or “link farming.” The process of creating a series of bogus Web sites, all linking back to the pages one is trying to promote., and Google actively works to uncover and shut down such efforts—see the “Link Fraudsters” sidebar).

Link Fraudsters, Be Prepared to Experience Google’s “Death Penalty”

JCPenney is a big retailer, for sure, but not necessarily the first firm to come to mind when you think of most retail categories. So the New York Times suspected that something fishy was up when the retailer’s site came out tops for dozens of Google searches, including the phrases “skinny jeans,” “dresses,” “bedding,” “area rugs,” “home decor,” “comforter sets,” “furniture,” and “table cloths”. The phrase “Samsonite carry on luggage” even placed Penney ahead of Samsonite’s own site!

The Times reported that “someone paid to have thousands of links placed on hundreds of sites scattered around the Web, all of which lead directly to JCPenney.com.” And there was little question it was blatant link fraud. Phrases related to dresses and linking back to the retailer were coming from such nondress sites as nuclear.engineeringaddict.com, casino-focus.com, and bulgariapropertyportal.com. One SEO expert called the effort the most ambitious link farming attempt he’d ever seen.

Link fraud undercuts the credibility of Google’s core search product, so when the search giant discovers a firm engaged in link farming they drop the hammer. In this case Google both manually demoted Penney rankings and launched tweaks to its ranking algorithm. Within two hours JCPenney organic results plummeted, in some cases from first to seventy-first (the Times calls this the organic search equivalent of the “death penalty”). Getting a top spot in Google search results is a big deal. On average, 34 percent of clicks go to the top result, about twice the percentage that goes to number two. Google’s punishment was administered despite the fact that Penney was also a large online ad customer, at times paying Google some $2.5 million a month for ads.D. Segal, “The Dirty Little Secrets of Search,” New York Times, February 12, 2011.

Google is constantly playing defense against firms gaming organic search results. In another example a Brooklyn-based eyewear firm allegedly mistreated customers in order to get more ranking-influencing links (albeit from negative mentions) from service review sites. For a time these associated with bad ratings actually pushed the eyewear firm’s search results ahead of rivals, and since users typically focus on the top ranking, many customers went to the firm without seeing the bad reviews (Google has since changed search results to make it difficult to benefit from cultivating negative reviews). The owner of the busted eyewear retailer has also pled guilty to multiple counts, including sending threatening communications, one count of mail fraud, and one count of wire fraud.D. Segal, “Online Seller Who Bullied Customers Pleads Guilty,” New York Times, May 12, 2011.

JCPenney isn’t the first firm busted. When Google discovered so-called black hat SEO was being used to push BMW up in organic search rankings, Google made certain BMW sites virtually unfindable in its organic search results. JCPenney claims that they were the victim of rogue behavior by an SEO consultant (who was promptly fired) and that the retailer was otherwise unaware of the unethical behavior. But it is surprising that the retailer’s internal team didn’t see their unbelievably successful organic search results as a red flag that something was amiss, and this case highlights the types of things managers need to watch for in the digital age. Penney outsourced SEO, and the fraud uncovered in this story underscores the critical importance of vetting and regularly auditing the performance of partners throughout a firm’s supply chain.D. Segal, “The Dirty Little Secrets of Search,” New York Times, February 12, 2011.

While Google doesn’t divulge specifics on the weighting of inbound links from a given Web site, we do know that links from some Web sites carry more weight than others. For example, links from Web sites that Google deems “influential” have greater weight in PageRank calculations than links from run-of-the-mill sites.

Spiders and Bots and Crawlers—Oh My!

When performing a search via Google or another search engine, you’re not actually searching the Web. What really happens is that the major search engines make what amounts to a copy of the Web, storing and indexing the text of online documents on their own computers. Google’s index considers over one trillion URLs.A. Wright, “Exploring a ‘Deep Web’ That Google Can’t Grasp,” New York Times, February 23, 2009. Google starts to retrieve results as soon as you begin to type, and the upper right-hand corner of a Google query shows you just how fast a search can take place.

To create these massive indexes, search firms use software to crawl the Web and uncover as much information as they can find. This software is referred to by several different names—spiders, Web crawlers, software robotsSoftware that traverses available Web links in an attempt to perform a given task. Search engines use spiders to discover documents for indexing and retrieval.—but they all pretty much work the same way. The spiders ask each public computer network for a list of its public Web sites (for more on this see DNS in Chapter 12 "A Manager’s Guide to the Internet and Telecommunications"). Then the spiders go through this list (“crawling” a site), following every available link until all pages are uncovered.

Google will crawl frequently updated sites, like those run by news organizations, as often as several times an hour. Rarely updated, less popular sites might only be reindexed every few days. The method used to crawl the Web also means that if a Web site isn’t the first page on a public server, or isn’t linked to from another public page, then it’ll never be found.Most Web sites do have a link where you can submit a Web site for indexing, and doing so can help promote the discovery of your content. Also note that each search engine also offers a page where you can submit your Web site for indexing.

While search engines show you what they’ve found on their copy of the Web’s contents; clicking a search result will direct you to the actual Web site, not the copy. But sometimes you’ll click a result only to find that the Web site doesn’t match what the search engine found. This happens if a Web site was updated before your search engine had a chance to reindex the changes. In most cases you can still pull up the search engine’s copy of the page. Just click the “Cached” link below the result (the term cacheA temporary storage space used to speed computing tasks. refers to a temporary storage space used to speed computing tasks).

But what if you want the content on your Web site to remain off limits to search engine indexing and caching? Organizations have created a set of standards to stop the spider crawl, and all commercial search engines have agreed to respect these standards. One way is to put a line of HTML code invisibly embedded in a Web page that tells all software robots to stop indexing a page, stop following links on the page, or stop offering old page archives in a cache. Users don’t see this code, but commercial Web crawlers do. For those familiar with HTML code (the language used to describe a Web site), the command to stop Web crawlers from indexing a page, following links, and listing archives of cached pages looks like this:

〈META NAME=“ROBOTS” CONTENT=“NOINDEX, NOFOLLOW, NOARCHIVE”〉

There are other techniques to keep the spiders out, too. Web site administrators can add a special file (called robots.txt) that provides similar instructions on how indexing software should treat the Web site. And a lot of content lies inside the “dark WebInternet content that can’t be indexed by Google and other search engines.,” either behind corporate firewalls or inaccessible to those without a user account—think of private Facebook updates no one can see unless they’re your friend—all of that is out of Google’s reach.

What’s It Take to Run This Thing?

Sergey Brin and Larry Page started Google with just four scavenged computers.M. Liedtke, “Google Reigns as World’s Most Powerful 10-Year-Old,” Associated Press, September 5, 2008. But in a decade, the infrastructure used to power the search sovereign has ballooned to the point where it is now the largest of its kind in the world.David F. Carr, “How Google Works,” Baseline, July 6, 2006. Google doesn’t disclose the number of servers it uses, but by some estimates, it runs over 1.4 million servers in over a dozen so-called server farmsA massive network of computer servers running software to coordinate their collective use. Server farms provide the infrastructure backbone to SaaS and hardware cloud efforts, as well as many large-scale Internet services. worldwide.R. Katz, “Tech Titans Building Boom,” IEEE Spectrum 46, no. 2 (February 1, 2009). In the first three months of 2011 alone, the firm spent $890 million on data centers.R. Miller, “Google Invests $890 Million in Data Centers,” Data Center Knowledge, April 15, 2011. Building massive server farms to index the ever-growing Web is now the cost of admission for any firm wanting to compete in the search market. This is clearly no longer a game for two graduate students working out of a garage.

Google’s Container Data Center

Take a virtual tour of one of Google’s data centers.

The size of this investment not only creates a barrier to entry, it influences industry profitability, with market-leader Google enjoying huge economies of scale. Firms may spend the same amount to build server farms, but if Google has roughly two-thirds of this market while Microsoft’s search draws just a fraction of this traffic, which do you think enjoys the better return on investment?

The hardware components that power Google aren’t particularly special. In most cases the firm uses the kind of Intel or AMD processors, low-end hard drives, and RAM chips that you’d find in a desktop PC. These components are housed in rack-mounted servers about 3.5 inches thick, with each server containing two processors, eight memory slots, and two hard drives.

In some cases, Google mounts racks of these servers inside standard-sized shipping containers, each with as many as 1,160 servers per box.S. Shankland, “Google Unlocks Once-Secret Server,” CNET, April 1, 2009. A given data center may have dozens of these server-filled containers all linked together. Redundancy is the name of the game. Google assumes individual components will regularly fail, but no single failure should interrupt the firm’s operations (making the setup what geeks call fault-tolerantCapable of continuing operation even if a component fails.). If something breaks, a technician can easily swap it out with a replacement.

Each server farm layout has also been carefully designed with an emphasis on lowering power consumption and cooling requirements. And the firm’s custom software (much of it built upon open source products) allows all this equipment to operate as the world’s largest grid computer.

Web search is a task particularly well suited for the massively parallel architecture used by Google and its rivals. For an analogy of how this works, imagine that working alone, you need try to find a particular phrase in a hundred-page document (that’s a one server effort). Next, imagine that you can distribute the task across five thousand people, giving each of them a separate sentence to scan (that’s the multi-server grid). This difference gives you a sense of how search firms use massive numbers of servers and the divide-and-conquer approach of grid computing to quickly find the needles you’re searching for within the Web’s haystack. (For more on grid computing, see Chapter 5 "Moore’s Law: Fast, Cheap Computing and What It Means for the Manager", and for more on server farms, see Chapter 10 "Software in Flux: Partly Cloudy and Sometimes Free".)

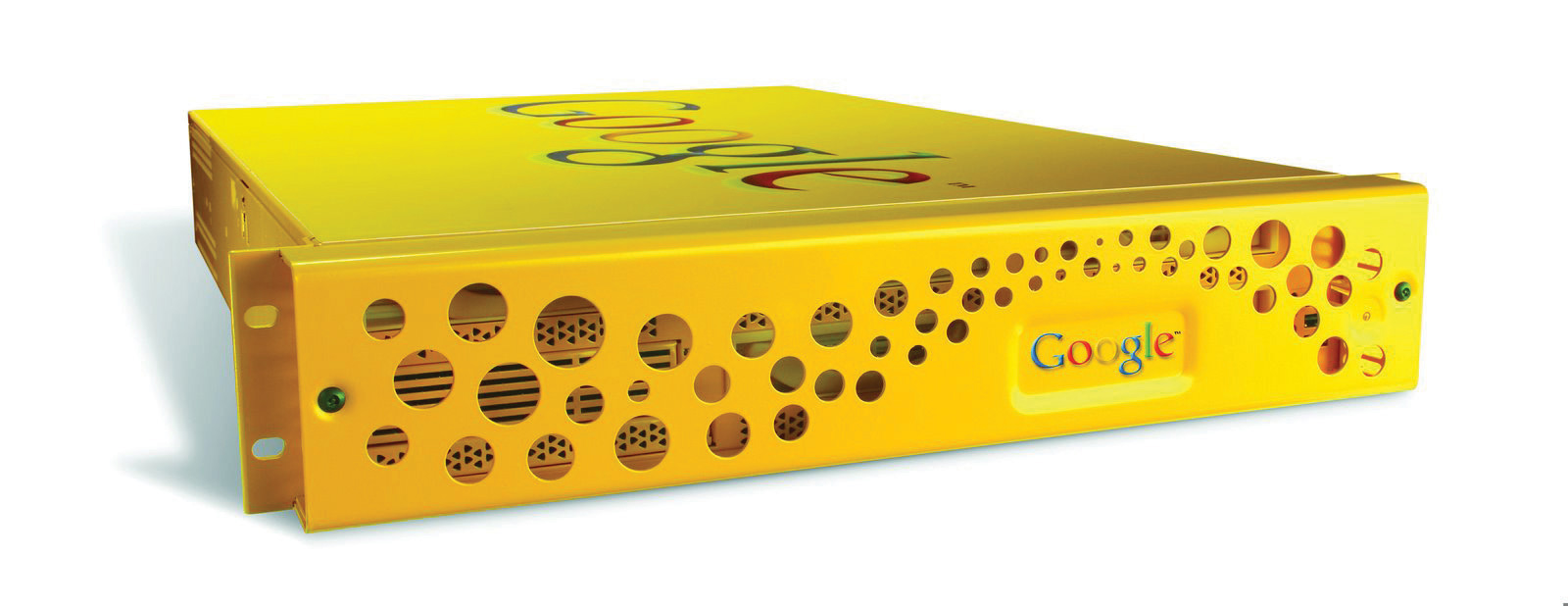

Figure 14.5

The Google Search Appliance is a hardware product that firms can purchase in order to run Google search technology within the privacy and security of an organization’s firewall.

Google will even sell you a bit of its technology so that you can run your own little Google in-house without sharing documents with the rest of the world. Google’s line of search appliances are rack-mounted servers that can index documents within the servers on a corporation’s own network, even managing user password and security access on a per-document basis. Selling hardware isn’t a large business for Google, and other vendors offer similar solutions, but search appliances can be vital tools for law firms, investment banks, and other document-rich organizations.

Trendspotting with Google

Google not only gives you search results, it lets you see aggregate trends in what its users are searching for, and this can yield powerful insights. For example, by tracking search trends for flu symptoms, Google’s Flu Trends Web site can pinpoint outbreaks one to two weeks faster than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.S. Bruce, “Google Says User Data Aids Flu Detection,” eHealthInsider, May 25, 2009. Want to go beyond the flu? Google’s Trends, and Insights for Search services allow anyone to explore search trends, breaking out the analysis by region, category (image, news, product), date, and other criteria. Savvy managers can leverage these and similar tools for competitive analysis, comparing a firm, its brands, and its rivals.

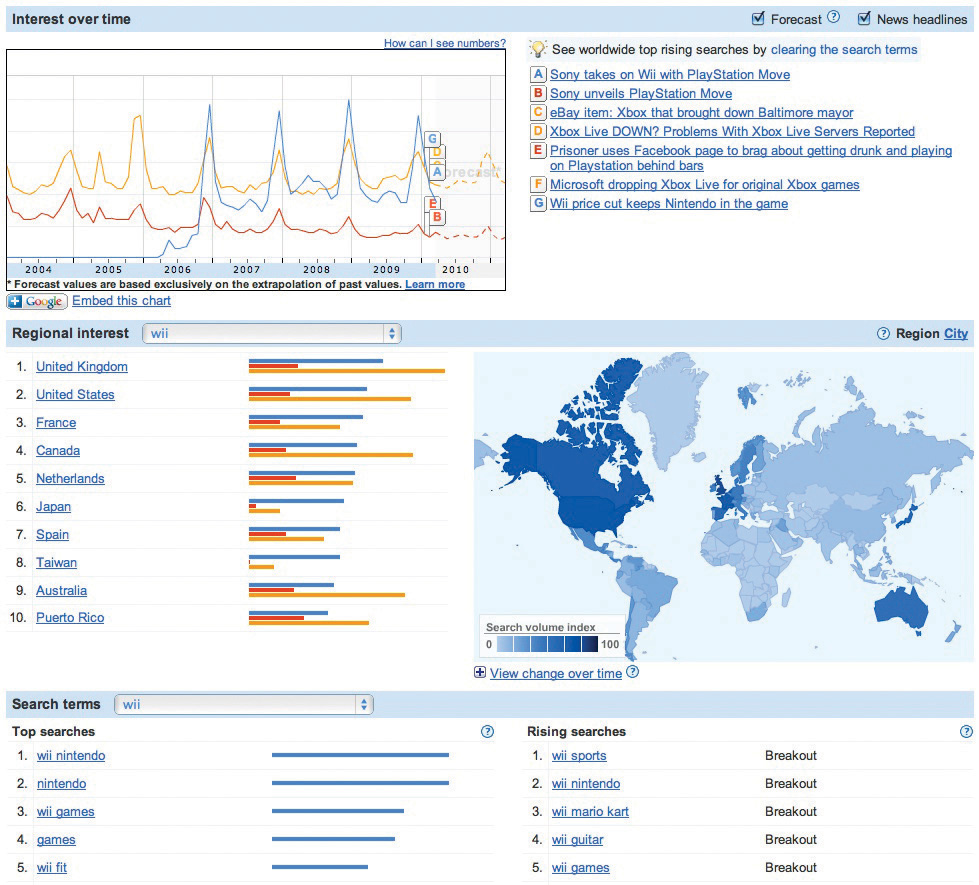

Figure 14.6

Google Insights for Search can be a useful tool for competitive analysis and trend discovery. This chart shows a comparison (over a twelve-month period, and geographically) of search interest in the terms Wii, Playstation, and Xbox.

Key Takeaways

- Ranked search results are often referred to as organic or natural search. PageRank is Google’s algorithm for ranking search results. PageRank orders organic search results based largely on the number of Web sites linking to them, and the “weight” of each page as measured by its “influence.”

- Search engine optimization (SEO) is the process of using natural or organic search to increase a Web site’s traffic volume and visitor quality. The scope and influence of search has made SEO an increasingly vital marketing function.

- Users don’t really search the Web; they search an archived copy built by crawling and indexing discoverable documents.

- Google operates from a massive network of server farms containing hundreds of thousands of servers built from standard, off-the-shelf items. The cost of the operation is a significant barrier to entry for competitors. Google’s share of search suggests the firm can realize economies of scales over rivals required to make similar investments while delivering fewer results (and hence ads).

- Web site owners can hide pages from popular search engine Web crawlers using a number of methods, including HTML tags, a no-index file, or ensuring that Web sites aren’t linked to other pages and haven’t been submitted to Web sites for indexing.

Questions and Exercises

- How do search engines discover pages on the Internet? What kind of capital commitment is necessary to go about doing this? How does this impact competitive dynamics in the industry?

- How does Google rank search results? Investigate and list some methods that an organization might use to improve its rank in Google’s organic search results. Are there techniques Google might not approve of? What risk does a firm run if Google or another search firm determines that it has used unscrupulous SEO techniques to try to unfairly influence ranking algorithms?

- Sometimes Web sites returned by major search engines don’t contain the words or phrases that initially brought you to the site. Why might this happen?

- What’s a cache? What other products or services have a cache?

- What can be done if you want the content on your Web site to remain off limits to search engine indexing and caching?

- What is a “search appliance”? Why might an organization choose such a product?

- Become a better searcher: Look at the advanced options for your favorite search engine. Are there options you hadn’t used previously? Be prepared to share what you learn during class discussion.

- Visit Google Trends and Google Insights for Search. Explore the tool as if you were comparing a firm with its competitors. What sorts of useful insights can you uncover? How might businesses use these tools?

- Some Web sites are accused of being “content farms,” offering low-quality content designed to attract searchers that include popular query terms and using this content to generate ad revenue. Demand Media, which went public at $1.5 billion, and Associated Content, which Yahoo! purchased for $100 million, have been accused of being content farms. Investigate the claims and visit these sites. Do you find the content useful? Do you think these sites are or are not content farms? Research how Google changed its ranking algorithm to penalize content farms. What has been the impact on these sites? Make a list of categories of firms and individuals that would likely be impacted by such moves. What does this tell you about Google’s influence?