This is “Distributed Computing”, section 9.4 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.3). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.4 Distributed Computing

Learning Objectives

- Understand the concept of distributed computing and its benefits.

- Understand the client-server model of distributed computing.

- Know what Web services are and the benefits that Web services bring to firms.

- Appreciate the importance of messaging standards and understand how sending messages between machines can speed processes, cut costs, reduce errors, and enable new ways of doing business.

When computers in different locations can communicate with one another, this is often referred to as distributed computingA form of computing where systems in different locations communicate and collaborate to complete a task.. Distributed computing can yield enormous efficiencies in speed, error reduction, and cost savings and can create entirely new ways of doing business. Designing systems architecture for distributed systems involves many advanced technical topics. Rather than provide an exhaustive decomposition of distributed computing, the examples that follow are meant to help managers understand the bigger ideas behind some of the terms that they are likely to encounter.

Let’s start with the term serverA program that fulfills the requests of a client.. This is a tricky one because it’s frequently used in two ways: (1) in a hardware context a server is a computer that has been configured to support requests from other computers (e.g., Dell sells servers) and (2) in a software context a server is a program that fulfills requests (e.g., the Apache open source Web server). Most of the time, server software resides on server-class hardware, but you can also set up a PC, laptop, or other small computer to run server software, albeit less powerfully. And you can use mainframe or super-computer-class machines as servers, too.

The World Wide Web, like many other distributed computing services, is what geeks call a client-server system. Client-server refers to two pieces of software, a clientA software program that makes requests of a server program. that makes a request, and a server that receives and attempts to fulfill the request. In our WWW scenario, the client is the browser (e.g., Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari). When you type a Web site’s address into the location field of your browser, you’re telling the client to “go find the Web server software at the address provided, and tell the server to return the Web site requested.”

It is possible to link simple scripting languages to a Web server for performing calculations, accessing databases, or customizing Web sites. But more advanced distributed environments may use a category of software called an application serverSoftware that houses and serves business logic for use (and reuse) by multiple applications.. The application server (or app server) houses business logic for a distributed system. Individual Web servicesSmall pieces of code that are accessed via the application server which permit interoperable machine-to-machine interaction over a network. served up by the app server are programmed to perform different tasks: returning a calculation (“sales tax for your order will be $11.58”), accessing a database program (“here are the results you searched for”), or even making a request to another server in another organization (“Visa, please verify this customer’s credit card number for me”).

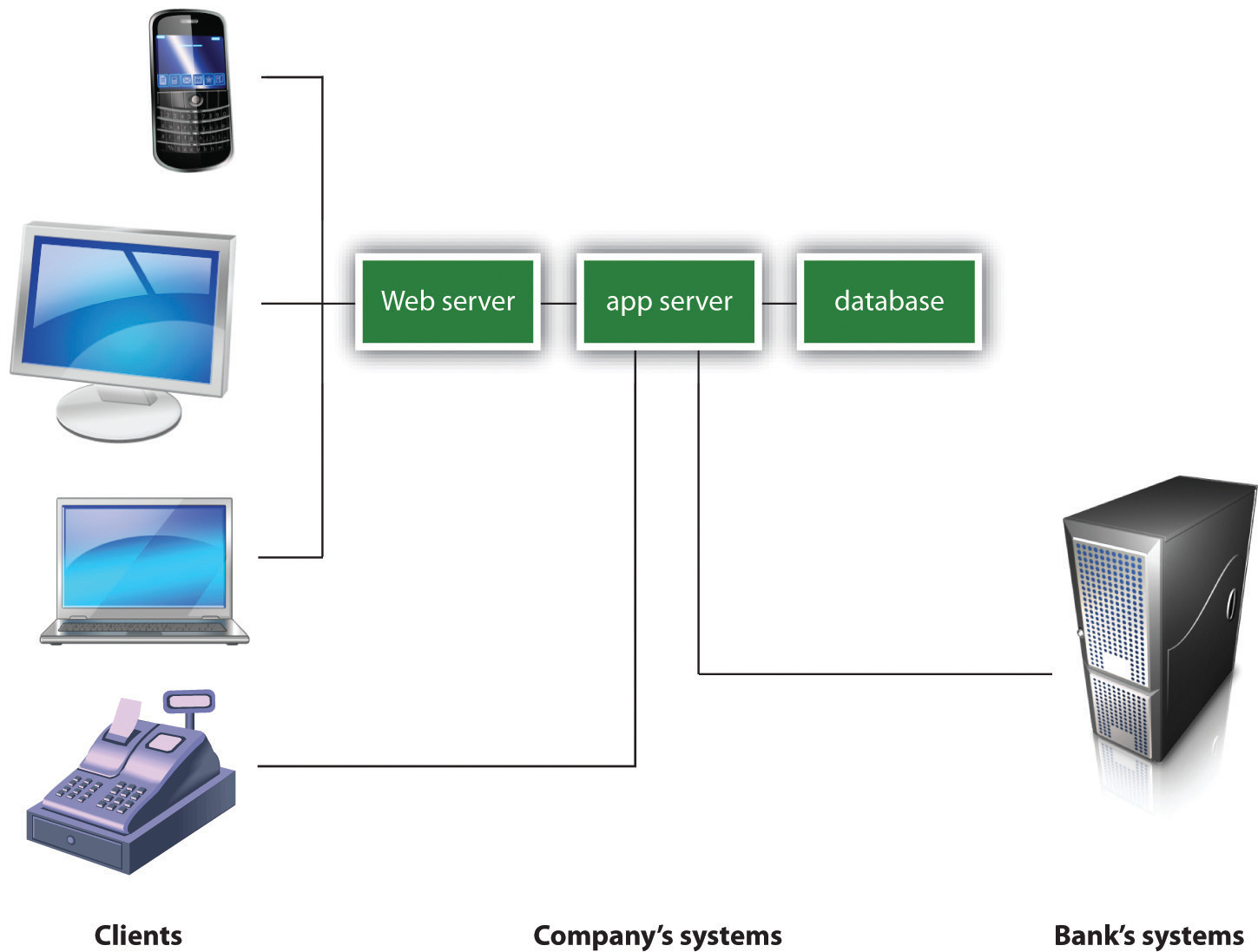

Figure 9.6

In this multitiered distributed system, client browsers on various machines (desktop, laptop, mobile) access the system through the Web server. The cash register doesn’t use a Web browser, so instead the cash register logic is programmed to directly access the services it needs from the app server. Web services accessed from the app server may be asked to do a variety of functions, including perform calculations, access corporate databases, or even make requests from servers at other firms (for example, to verify a customer’s credit card).

Those little chunks of code that are accessed via the application server are sometimes referred to as Web services. The World Wide Web consortium defines Web services as software systems designed to support interoperable machine-to-machine interaction over a network.W3C, “Web Services Architecture,” W3C Working Group Note, February 11, 2004. And when computers can talk together (instead of people), this often results in fewer errors, time savings, cost reductions, and can even create whole new ways of doing business! Each Web service defines the standard method for other programs to request it to perform a task and defines the kind of response the calling client can expect back. These standards are referred to as application programming interfaces (APIs)Programming hooks, or guidelines, published by firms that tell other programs how to get a service to perform a task such as send or receive data. For example, Amazon.com provides APIs to let developers write their own applications and Websites that can send the firm orders..

Look at the advantages that Web services bring a firm like Amazon. Using Web services, the firm can allow the same order entry logic to be used by Web browsers, mobile phone applications, or even by third parties who want to access Amazon product information and place orders with the firm (there’s an incentive to funnel sales to Amazon—the firm will give you a cut of any sales that you send Amazon’s way). Organizations that have created a robust set of Web services around their processes and procedures are said to have a service-oriented architecture (SOA)A robust set of Web services built around an organizations processes and procedures.. Organizing systems like this, with separate applications in charge of client presentation, business logic, and database, makes systems more flexible. Code can be reused, and each layer can be separately maintained, upgraded, or migrated to new hardware—all with little impact on the others.

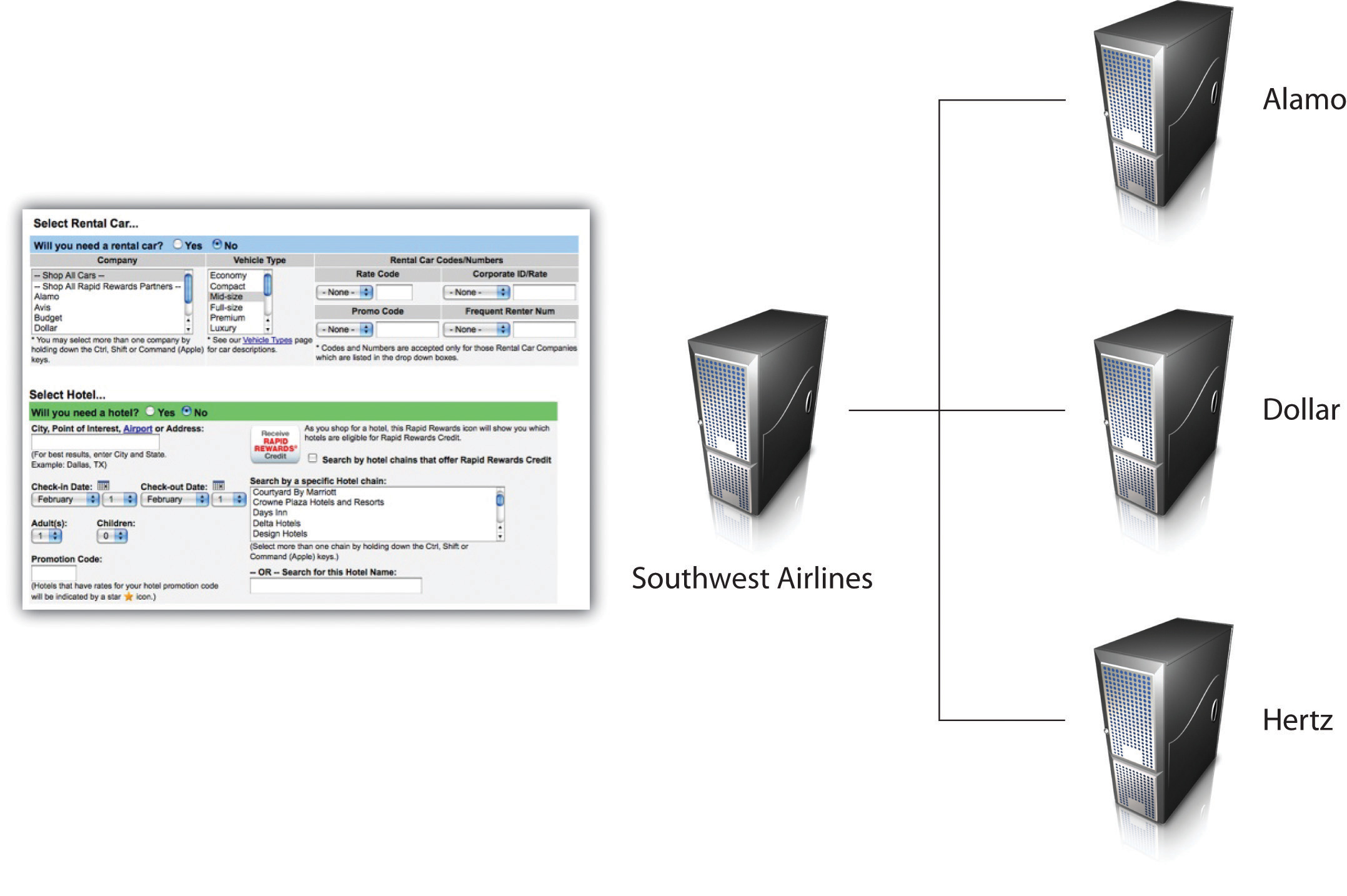

Web services sound geeky, but here’s a concrete example illustrating their power. Southwest Airlines had a Web site where customers could book flights, but many customers also wanted to rent a car or book a hotel, too. To keep customers on Southwest.com, the firm and its hotel and rental car partners created a set of Web services and shared the APIs. Now customers visiting Southwest.com can book a hotel stay and rental car on the same page where they make their flight reservation. This process transforms Southwest.com into a full service travel destination and allows the site to compete head-to-head with the likes of Expedia, Travelocity, and Orbitz.J. McCarthy, “The Standards Body Politic,” InfoWorld, May 17, 2002.

Think about why Web services are important from a strategic perspective. By adding hotel and rental car services, Southwest is now able to eliminate the travel agent, along with any fees they might share with the agent. This shortcut allows the firm to capture more profits or pass on savings to customers, securing its position as the first place customers go for low-cost travel. And perhaps most importantly, Southwest can capture key data from visitor travel searches and bookings (something it likely couldn’t do if customers went to a site like Expedia or Travelocity). Data is a hugely valuable asset, and this kind of customer data can be used by Southwest to send out custom e-mail messages and other marketing campaigns to bring customers back to the airline. As geeky as they might at first seem, Web services can be very strategic!

Figure 9.7

Southwest.com uses Web services to allow car rental and hotel firms to book services through Southwest. This process transforms Southwest.com into a full-service online travel agent.

Formats to Facilitate Sharing Data

Two additional terms you might hear within the context of distributed computing are EDI and XML. EDI (electronic data interchange)A set of standards for exchanging messages containing formatted data between computer applications. is a set of standards for exchanging information between computer applications. EDI is most often used as a way to send the electronic equivalent of structured documents between different organizations. Using EDI, each element in the electronic document, such as a firm name, address, or customer number, is coded so that it can be recognized by the receiving computer program. Eliminating paper documents makes businesses faster and lowers data entry and error costs. One study showed that firms that used EDI decreased their error rates by 82 percent, and their cost of producing each document fell by up to 96 percent.“Petroleum Industry Continues to Explore EDI,” National Petroleum News 90, no. 12 (November 1998).

EDI is a very old standard, with roots stretching back to the 1948 Berlin Air Lift. While still in use, a new generation of more-flexible technologies for specifying data standards are taking its place. Chief among the technologies replacing EDI is extensible markup language (XML)A tagging language that can be used to identify data fields made available for use by other applications. Most APIs and Web services send messages where the data exchanged is wrapped in identifying XML tags.. XML has lots of uses, but in the context of distributed systems, it allows software developers to create a set of standards for common data elements that, like EDI messages, can be sent between different kinds of computers, different applications, and different organizations. XML is often thought of as easier to code than EDI, and it’s more robust because it can be extended—organizations can create formats to represent any kind of data (e.g., a common part number, photos, the complaint field collected by customer support personnel). In fact, most messages sent between Web services are coded in XML (the technology is a key enabler in mash-ups, discussed in Chapter 7 "Social Media, Peer Production, and Web 2.0"). Many computer programs also use XML as a way to export and import data in a common format that can be used regardless of the kind of computer hardware, operating system, or application program used. And if you design Web sites, you might encounter XML as part of the coding behind the cascading style sheets (CSS) that help maintain a consistent look and feel to the various Web pages in a given Web site.

Rearden Commerce: A Business Built on Web Services

Web services, APIs, and open standards not only transform businesses, they can create entire new firms that change how we get things done. For a look at the mashed-up, integrated, hyperautomated possibilities that Web services make possible, check out Rearden Commerce, a Foster City, California, firm that is using this technology to become what AMR’s Chief Research Office referred to as “Travelocity on Steroids.”

Using Rearden, firms can offer their busy employees a sort of Web-based concierge/personal assistant. Rearden offers firms a one-stop shop where employees can not only make the flight, car, and hotel bookings they might do from a travel agent, they can also book dinner reservations, sports and theatre tickets, and arrange for business services like conference calls and package shipping. Rearden doesn’t supply the goods and services it sells. Instead it acts as the middleman between transactions. A set of open APIs to its Web services allows Rearden’s one hundred and sixty thousand suppliers to send product and service data to Rearden, and to receive booking and sales data from the site.

In this ultimate business mash-up, a mobile Rearden user could use her phone to book a flight into a client city, see restaurants within a certain distance of her client’s office, have these locations pop up on a Google map, have listings accompanied by Zagat ratings and cuisine type, book restaurant reservations through Open Table, arrange for a car and driver to meet her at her client’s office at a specific time, and sync up these reservations with her firm’s corporate calendaring systems. If something unexpected comes up, like a flight delay, Rearden will be sure she gets the message. The system will keep track of any cancelled reservation credits, and also records travel reward programs, so Rearden can be used to spend those points in the future.

In order to pull off this effort, the Rearden maestros are not only skilled at technical orchestration, but also in coordinating customer and supplier requirements. As TechCrunch’s Erick Schonfeld put it, “The hard part is not only the technology—which is all about integrating an unruly mess of APIs and Web services—[it also involves] signing commercially binding service level agreements with [now over 160,000] merchants across the world.” For its efforts, Rearden gets to keep between 6 percent and 25 percent of every nontravel dollar spent, depending on the service. The firm also makes money from subscriptions, and distribution deals.

The firm’s first customers were large businesses and included ConAgra, GlaxoSmithKline, and Motorola. Rearden’s customers can configure the system around special parameters unique to each firm: to favor a specific airline, benefit from a corporate discount, or to restrict some offerings for approved employees only. Rearden investors include JPMorgan Chase and American Express—both of whom offer Rearden to their employees and customers. Even before the consumer version was available, Rearden had over four thousand corporate customers and two million total users, a user base larger than better-known firms like Salesforce.com.M. Arrington, “Rearden Commerce: Time for the Adults to Come In and Clean House,” TechCrunch, April 5, 2007; E. Schonfeld, “At Rearden Commerce, Addiction Is Job One,” TechCrunch, May 6, 2008; and M. Arrington, “2008: Rearden Commerce Has a Heck of a Year,” TechCrunch, January 13, 2009. For all the pizzazz we recognize that, as a start-up, the future of Rearden Commerce remains uncertain; however, the firm’s effective use of Web services illustrates the business possibilities as technologies allow firms to connect with greater ease and efficiency.

Connectivity has made our systems more productive and enables entire new strategies and business models. But these wonderful benefits come at the price of increased risk. When systems are more interconnected, opportunities for infiltration and abuse also increase. Think of it this way—each “connection” opportunity is like adding another door to a building. The more doors that have to be defended, the more difficult security becomes. It should be no surprise that the rise of the Internet and distributed computing has led to an explosion in security losses by organizations worldwide.

Key Takeaways

- Client-server computing is a method of distributed computing where one program (a client) makes a request to be fulfilled by another program (a server).

- Server is a tricky term and is sometimes used to refer to hardware. While server-class hardware refers to more powerful computers designed to support multiple users, just about any PC or notebook can be configured to run server software.

- Web servers serve up Web sites and can perform some scripting.

- Most firms serve complex business logic from an application server.

- Isolating a system’s logic in three or more layers (presentation or user interface, business logic, and database) can allow a firm flexibility in maintenance, reusability, and in handling upgrades.

- Web services allow different applications to communicate with one another. APIs define the method to call a Web service (e.g., to get it to do something), and the kind of response the calling program can expect back.

- Web services make it easier to link applications as distributed systems, and can make it easier for firms to link their systems across organizations.

- Popular messaging standards include EDI (older) and XML. Sending messages between machines instead of physical documents can speed processes, drastically cut the cost of transactions, and reduce errors.

- Distributed computing can yield enormous efficiencies in speed, error reduction, and cost savings and can create entirely new ways of doing business.

- When computers can communicate with each other (instead of people), this often results in fewer errors, time savings, cost reductions, and can even create whole new ways of doing business.

- Web services, APIs, and open standards not only transform businesses, they can create entire new firms that change how we get things done.

Questions and Exercises

- Differentiate the term “server” used in a hardware context, from “server” used in a software context.

- Describe the “client-server” model of distributed computing. What products that you use would classify as leveraging client-server computing?

- List the advantages that Web services have brought to Amazon.

- How has Southwest Airlines utilized Web services to its competitive advantage?

- What is Rearden Commerce and which technologies does it employ? Describe Rearden Technology’s revenue model. Who were Rearden Technology’s first customers? Who were among their first investors?

- What are the security risks associated with connectivity, the Internet, and distributed processing?