This is “Bringing Brains Together: Supercomputing and Grid Computing”, section 5.3 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems (v. 1.3). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.3 Bringing Brains Together: Supercomputing and Grid Computing

Learning Objectives

- Give examples of the business use of supercomputing and grid computing.

- Describe grid computing and discuss how grids transform the economics of supercomputing.

- Understand the characteristics of problems that are and are not well suited for supercomputing and grid computing.

As Moore’s Law makes possible the once impossible, businesses have begun to demand access to the world’s most powerful computing technology. SupercomputersComputers that are among the fastest of any in the world at the time of their introduction. are computers that are among the fastest of any in the world at the time of their introduction.A list of the current supercomputer performance champs can be found at http://www.top500.org. Supercomputing was once the domain of governments and high-end research labs, performing tasks such as simulating the explosion of nuclear devices, or analyzing large-scale weather and climate phenomena. But it turns out with a bit of tweaking, the algorithms used in this work are profoundly useful to business. Consider perhaps the world’s most well-known supercomputer, IBM’s Deep Blue, the machine that rather controversially beat chess champion Garry Kasparov. While there is not a burning need for chess-playing computers in the world’s corporations, it turns out that the computing algorithms to choose the best among multiple chess moves are similar to the math behind choosing the best combination of airline flights.

Paging Doctor Watson

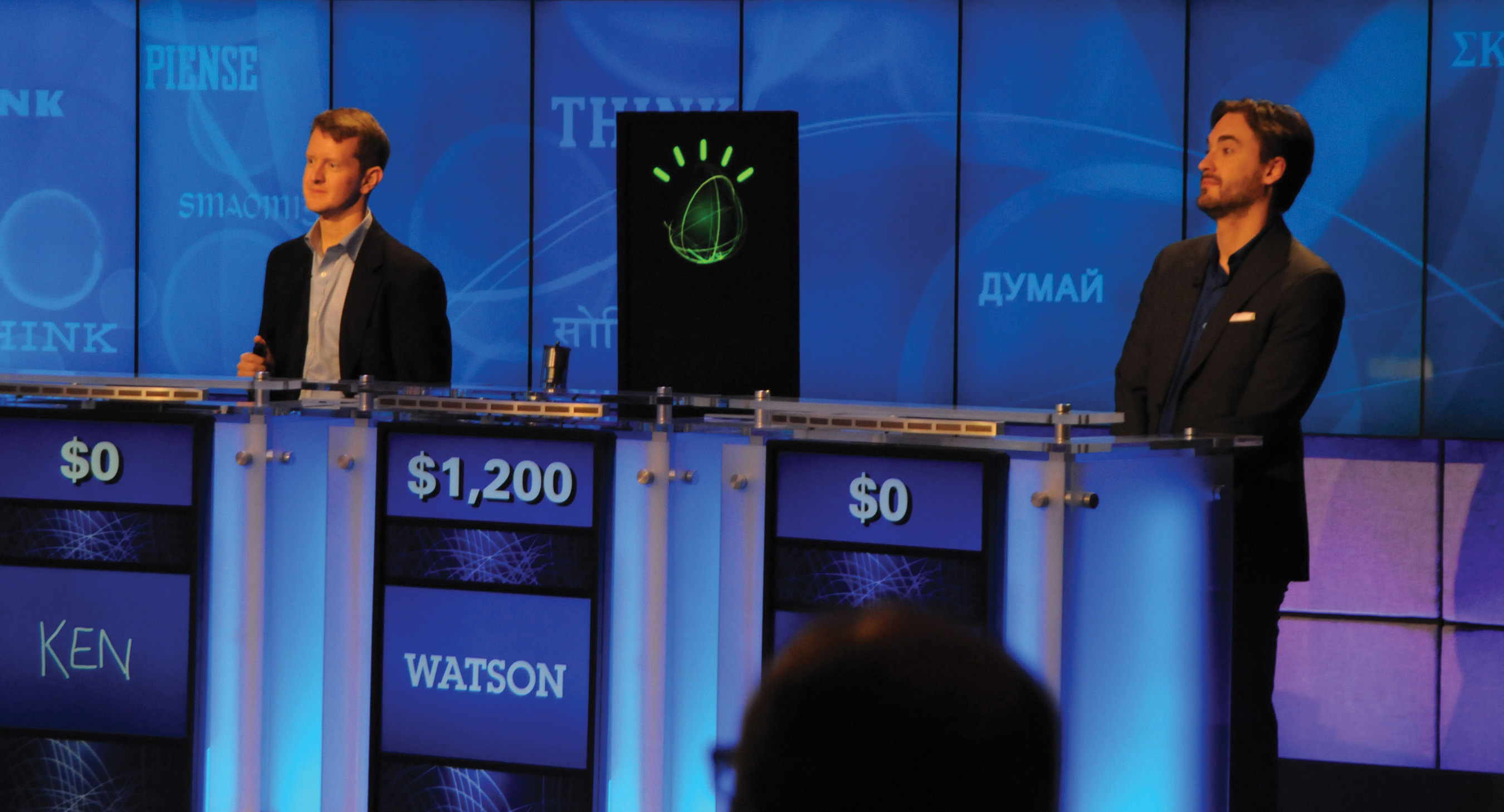

In spring 2011, the world was introduced to another IBM supercomputer—the Jeopardy-playing Watson. Built to quickly answer questions posed in natural language, by the end of a televised three-day tournament Watson had put the hurt on prior Jeopardy champs Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter, trouncing the human rivals and winning one million dollars (donated to a children’s charity). Watson’s accomplishment represented a four-year project that involved some twenty-five people across eight IBM research labs, creating algorithms, in a system with ninety servers, “many, many” processors, terabytes of storage, and “tens of millions of dollars” in investment.L. Sumagaysay, “After Man vs. Machine on ‘Jeopardy,’ What’s Next for IBM’s Watson?” Good Morning Silicon Valley, February 17, 2011. Winning Jeopardy makes for a few nights of interesting TV, but what else can it do? Well, the “Deep QA” technology behind Watson might end up in your doctor’s office, and docs could likely use that kind of “exobrain.” On average “primary care physicians spend less than twenty minutes face-to-face with each patient per visit, and average little more than an hour each week reading medical journals.”C. Nickisch, “IBM to Roll Out Watson, M.D.,” WBUR, February 18, 2011. Now imagine a physician assistant Watson that could leverage massive diagnosis databases while scanning hundreds of pages in a person’s medical history, surfacing a best guess at what docs should be paying attention to. A JAMA study suggested that medical errors may be the third leading cause of death in the United States,B. Starfield, “Is U.S. Health Really the Best in the World?” Journal of the American Medical Association, July 26, 2000. so there’s apparently an enormous and mighty troubling opportunity in health care alone. IBM is partnering with Massachusetts voice-rec leader Nuance Communications (the Dragon people) to bring Watson to the doc’s office. Med schools at Columbia and the University of Maryland will help with the research effort. Of course, you wouldn’t want to completely trust a Watson recommendation. While Watson was good enough to be tournament champ, IBM’s baby missed a final Jeopardy answer of “Chicago” because it answered that Toronto was a U.S. city.

Source: http://www.ibm.com/press.

One of the first customers of Deep Blue technologies was United Airlines, which gained an ability to examine three hundred and fifty thousand flight path combinations for its scheduling systems—a figure well ahead of the previous limit of three thousand. Estimated savings through better yield management? Over $50 million! Finance found uses, too. An early adopter was CIBC (the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce), one of the largest banks in North America. Each morning CIBC uses a supercomputer to run its portfolio through Monte Carlo simulations that aren’t all that different from the math used to simulate nuclear explosions. An early adopter of the technology, at the time of deployment, CIBC was the only bank that international regulators allowed to calculate its own capital needs rather than use boilerplate ratios. That cut capital on hand by hundreds of millions of dollars, a substantial percentage of the bank’s capital, saving millions a year in funding costs. Also noteworthy: the supercomputer-enabled, risk-savvy CIBC was relatively unscathed by the subprime crisis.

Modern supercomputing is typically done via a technique called massively parallelComputers designed with many microprocessors that work together, simultaneously, to solve problems. processing (computers designed with many microprocessors that work together, simultaneously, to solve problems). The fastest of these supercomputers are built using hundreds of microprocessors, all programmed to work in unison as one big brain. While supercomputers use special electronics and software to handle the massive load, the processors themselves are often of the off-the-shelf variety that you’d find in a typical PC. Virginia Tech created what at the time was the world’s third-fastest supercomputer by using chips from 1,100 Macintosh computers lashed together with off-the-shelf networking components. The total cost of the system was just $5.2 million, far less than the typical cost for such burly hardware. The Air Force recently issued a request-for-proposal to purchase 2,200 PlayStation 3 systems in hopes of crafting a supercheap, superpowerful machine using off-the-shelf parts.

Another technology, known as grid computingA type of computing that uses special software to enable several computers to work together on a common problem as if they were a massively parallel supercomputer., is further transforming the economics of supercomputing. With grid computing, firms place special software on its existing PCs or servers that enables these computers to work together on a common problem. Large organizations may have thousands of PCs, but they’re not necessarily being used all the time, or at full capacity. With grid software installed on them, these idle devices can be marshaled to attack portions of a complex task as if they collectively were one massively parallel supercomputer. This technique radically changes the economics of high-performance computing. BusinessWeek reports that while a middle-of-the-road supercomputer could run as much as $30 million, grid computing software and services to perform comparable tasks can cost as little as twenty-five thousand dollars, assuming an organization already has PCs and servers in place.

An early pioneer in grid computing is the biotech firm Monsanto. Monsanto enlists computers to explore ways to manipulate genes to create crop strains that are resistant to cold, drought, bugs, pesticides, or that are more nutritious. Previously with even the largest computer Monsanto had in-house, gene analysis was taking six weeks and the firm was able to analyze only ten to fifty genes a year. But by leveraging grid computing, Monsanto has reduced gene analysis to less than a day. The fiftyfold time savings now lets the firm consider thousands of genetic combinations in a year.P. Schwartz, C. Taylor, and R. Koselka, “The Future of Computing: Quantum Leap,” Fortune, August 2, 2006. Lower R&D time means faster time to market—critical to both the firm and its customers.

Grids are now everywhere. Movie studios use them to create special effects and animated films. Proctor & Gamble has used grids to redesign the manufacturing process for Pringles potato chips. GM and Ford use grids to simulate crash tests, saving millions in junked cars and speeding time to market. Pratt and Whitney test aircraft engine designs on a grid. And biotech firms including Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer push their research through a quicker pipeline by harnessing grid power. JP Morgan Chase even launched a grid effort that mimics CIBC’s supercomputer, but at a fraction of the latter’s cost. By the second year of operation, the JPMorgan Chase grid was saving the firm $5 million per year.

You can join a grid, too. SETI@Home turns your computer screen saver into a method to help “search for extraterrestrial intelligence,” analyzing data from the Arecibo radio telescope system in Puerto Rico (no E.T. spotted yet). FightAids@Home will enlist your PC to explore AIDS treatments. And Folding@Home is an effort by Stanford researchers to understanding the science of protein-folding within diseases such as Alzheimer’s, cancer, and cystic fibrosis. A version of Folding@Home software for the PlayStation 3 had enlisted over half a million consoles within months of release. Having access to these free resources is an enormous advantage for researchers. Says the director of Folding@Home, “Even if we were given all of the NSF supercomputing centers combined for a couple of months, that is still fewer resources than we have now.”G. Johnson, “Supercomputing ‘@Home’ Is Paying Off,” New York Times, April 23, 2002.

Multicore, massively parallel, and grid computing are all related in that each attempts to lash together multiple computing devices so that they can work together to solve problems. Think of multicore chips as having several processors in a single chip. Think of massively parallel supercomputers as having several chips in one computer, and think of grid computing as using existing computers to work together on a single task (essentially a computer made up of multiple computers). While these technologies offer great promise, they’re all subject to the same limitation: software must be written to divide existing problems into smaller pieces that can be handled by each core, processor, or computer, respectively. Some problems, such as simulations, are easy to split up, but for problems that are linear (where, for example, step two can’t be started until the results from step one are known), the multiple-brain approach doesn’t offer much help.

Massive clusters of computers running software that allows them to operate as a unified service also enable new service-based computing models, such as software as a service (SaaS)A form of cloud computing where a firm subscribes to a third-party software and receives a service that is delivered online. and cloud computingReplacing computing resources—either an organization’s or individual’s hardware or software—with services provided over the Internet.. In these models, organizations replace traditional software and hardware that they would run in-house with services that are delivered online. Google, Microsoft, Salesforce.com, and Amazon are among the firms that have sunk billions into these Moore’s Law–enabled server farmsA massive network of computer servers running software to coordinate their collective use. Server farms provide the infrastructure backbone to SaaS and hardware cloud efforts, as well as many large-scale Internet services., creating entirely new businesses that promise to radically redraw the software and hardware landscape while bringing gargantuan computing power to the little guy. (See Chapter 10 "Software in Flux: Partly Cloudy and Sometimes Free".)

Moore’s Law will likely hit its physical limit in your lifetime, but no one really knows if this “Moore’s Wall” is a decade away or more. What lies ahead is anyone’s guess. Some technologies, such as still-experimental quantum computing, could make computers that are more powerful than all the world’s conventional computers combined. Think strategically—new waves of innovation might soon be shouting “surf’s up!”

Key Takeaways

- Most modern supercomputers use massive sets of microprocessors working in parallel.

- The microprocessors used in most modern supercomputers are often the same commodity chips that can be found in conventional PCs and servers.

- Moore’s Law means that businesses as diverse as financial services firms, industrial manufacturers, consumer goods firms, and film studios can now afford access to supercomputers.

- Grid computing software uses existing computer hardware to work together and mimic a massively parallel supercomputer. Using existing hardware for a grid can save a firm the millions of dollars it might otherwise cost to buy a conventional supercomputer, further bringing massive computing capabilities to organizations that would otherwise never benefit from this kind of power.

- Massively parallel computing also enables the vast server farms that power online businesses like Google and Facebook, and which create new computing models, like software as a service (SaaS) and cloud computing.

- The characteristics of problems best suited for solving via multicore systems, parallel supercomputers, or grid computers are those that can be divided up so that multiple calculating components can simultaneously work on a portion of the problem. Problems that are linear—where one part must be solved before moving to the next and the next—may have difficulty benefiting from these kinds of “divide and conquer” computing. Fortunately many problems such as financial risk modeling, animation, manufacturing simulation, and gene analysis are all suited for parallel systems.

Questions and Exercises

- What is the difference between supercomputing and grid computing? How is each phenomenon empowered by Moore’s Law?

- How does grid computing change the economics of supercomputing?

- Which businesses are using supercomputing and grid computing? Describe these uses and the advantages they offer their adopting firms. Are they a source of competitive advantage? Why or why not?

- What are the characteristics of problems that are most easily solved using the types of parallel computing found in grids and modern day supercomputers? What are the characteristics of the sorts of problems not well suited for this type of computing?

- Visit the SETI@Home Web site (http://seti.ssl.berkeley.edu). What is the purpose of the SETI@Home project? How do you participate? Is there any possible danger to your computer if you choose to participate? (Read their rules and policies.)

- Search online to identify the five fastest supercomputers currently in operation. Who sponsors these machines? What are they used for? How many processors do they have?

- What is “Moore’s Wall”?

- What is the advantage of using grid computing to simulate an automobile crash test as opposed to actually staging a crash?