This is “Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph”, chapter 8 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 8 Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph

8.1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Be familiar with Facebook’s origins and rapid rise.

- Understand how Facebook’s rapid rise has impacted the firm’s ability to raise venture funding and its founder’s ability to maintain a controlling interest in the firm.

Here’s how much of a Web 2.0 guy Mark Zuckerberg is: during the weeks he spent working on Facebook as a Harvard sophomore, he didn’t have time to study for a course he was taking, “Art in the Time of Augustus,” so he built a Web site containing all of the artwork in class and pinged his classmates to contribute to a communal study guide. Within hours, the wisdom of crowds produced a sort of custom CliffsNotes for the course, and after reviewing the Web-based crib sheet, he aced the test. Turns out he didn’t need to take that exam, anyway. Zuck (that’s what the cool kids call him)For an insider account of Silicon Valley Web 2.0 start-ups, see Sarah Lacy, Once You’re Lucky, Twice You’re Good: The Rebirth of Silicon Valley and the Rise of Web 2.0. (New York: Gotham Books, 2008). dropped out of Harvard later that year.

Zuckerberg is known as both a shy, geeky, introvert who eschews parties, and as a brash Silicon Valley bad boy. After Facebook’s incorporation, Zuckerberg’s job description was listed as “Founder, Master and Commander [and] Enemy of the State.”T. McGinn, “Online Facebooks Duel over Tangled Web of Authorship,” Harvard Crimson, May 28, 2004. An early business card read “I’m CEO...Bitch.”C. Hoffman, “The Battle for Facebook,” Rolling Stone, June 26, 2008, 9. And let’s not forget that Facebook came out of drunken experiments in his dorm room, one of which was a system for comparing classmates to farm animals (Zuckerberg, threatened with expulsion, later apologized). For one meeting with Sequoia Capital, the venerable Menlo Park venture capital firm that backed Google and YouTube, Zuckerberg showed up in his pajamas.C. Hoffman, “The Battle for Facebook,” Rolling Stone, June 26, 2008.

By the age of twenty-three, Mark Zuckerberg had graced the cover of Newsweek, been profiled on 60 Minutes, and was discussed in the tech world with a reverence previously reserved only for Steve Jobs and the Google guys, Sergey Brin and Larry Page. But Mark Zuckerberg’s star rose much faster than any of his predecessors. Just two weeks after Facebook launched, the firm had four thousand users. Ten months later it was up to one million. The growth continued, and the business world took notice. In 2006, Viacom (parent of MTV) saw that its core demographic was spending a ton of time on Facebook and offered to buy the firm for three quarters of a billion dollars. Zuckerberg passed.S. Rosenbush, “Facebook’s on the Block,” BusinessWeek, March 28, 2006. Yahoo! offered up a cool billion (twice). Zuck passed again, both times.

As growth skyrocketed, Facebook built on its stranglehold of the college market (over 85 percent of four-year college students are Facebook members), opening up first to high schoolers, then to everyone. Web hipsters started selling shirts emblazoned with “I Facebooked your Mom!” Even Microsoft wanted some of Facebook’s magic. In 2006, the firm temporarily locked up the right to broker all banner ad sales that run on the U.S. version of Facebook, guaranteeing Zuckerberg’s firm $100 million a year through 2011. In 2007, Microsoft came back, buying 1.6 percent of the firm for $240 million.While Microsoft had cut deals to run banner ads worldwide, Facebook dropped banner ads for poor performance in early 2010; see C. McCarthy, “More Social, Please: Facebook Nixes Banner Ads”, CNET, February 5, 2010.

The investment was a shocker. Do the math and a 1.6 percent stake for $240 million values Facebook at $15 billion (more on that later). That meant that a firm that at the time had only five hundred employees, $150 million in revenues, and was helmed by a twenty-three-year-old college dropout in his first “real job,” was more valuable than General Motors. Rupert Murdoch, whose News Corporation owns rival MySpace, engaged in a little trash talk, referring to Facebook as “the flavor of the month.”B. Morrissey, “Murdoch: Facebook Is ‘Flavor of the Month,’” Media Week, June 20, 2008.

Watch your back, Rupert. Or on second thought, watch Zuckerberg’s. By spring 2009, Facebook had more than twice MySpace’s monthly unique visitors worldwide;E. Schonfeld, “Dear Owen, Good Luck with That,” TechCrunch, April 24, 2009. by June, Facebook surpassed MySpace in the United States;“Facebook Dethrones MySpace in the U.S.,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2009, http://articles.latimes.com/2009/jun/16/business/fi-facebook16. by July, Facebook was cash-flow positiveWhen a company’s revenues can cover its operating costs.; and by February 2010 (when Facebook turned six), the firm had over four hundred million users, more than doubling in size in less than a year.D. Gage, “Facebook Claims 250 Million Users,” InformationWeek, July 16, 2009. Murdoch, the media titan who stood atop an empire that includes the Wall Street Journal and Fox, had been outmaneuvered by “the kid.”

Why Study Facebook?

Looking at the “flavor of the month” and trying to distinguish the reality from the hype is a critical managerial skill. In Facebook’s case, there are a lot of folks with a vested interest in figuring out where the firm is headed. If you want to work there, are you signing on to a firm where your stock options and 401k contributions are going to be worth something or worthless? If you’re an investor and Facebook goes publicThe first time a firm sells stock to the public; formally called an initial public stock offering (IPO)., should you shortShort selling is an attempt to profit from a falling stock price. Short sellers sell shares they don’t own with an obligation of later repayment. They do so in the hope that the price of sold shares will fall. They then repay share debt with shares purchased at a lower price and pocket the difference (spread) between initial share price and repayment price. the firm or increase your holdings? Would you invest in or avoid firms that rely on Facebook’s business? Should your firm rush to partner with the firm? Would you extend the firm credit? Offer it better terms to secure its growing business, or worse terms because you think it’s a risky bet? Is this firm the next Google (underestimated at first, and now wildly profitable and influential), the next GeoCities (Yahoo! paid $3 billion for it—no one goes to the site today), or the next Skype (deeply impactful with over half a billion accounts worldwide, but not much of a profit generator)? The jury is still out on all this, but let’s look at the fundamentals with an eye to applying what we’ve learned. No one has a crystal ball, but we do have some key concepts that can guide our analysis. There are a lot of broadly applicable managerial lessons that can be gleaned by examining Facebook’s successes and missteps. Studying the firm provides a context for examining nework effects, platforms, partnerships, issues in the rollout of new technologies, privacy, ad models, and more.

Zuckerberg Rules!

Many entrepreneurs accept start-up capital from venture capitalists (VCs)Investor groups that provide funding in exchange for a stake in the firm, and often, a degree of managerial control (usually in the form of a voting seat or seats on the firm’s board of directors)., investor groups that provide funding in exchange for a stake in the firm, and often, a degree of managerial control (usually in the form of a voting seat or seats on the firm’s board of directorsGroup assigned to govern, advise, and provide oversight for the firm. The board’s many responsibilities typically include hiring and firing the CEO.). Typically, the earlier a firm accepts VC money, the more control these investors can exert (earlier investments are riskier, so VCs can demand more favorable terms). VCs usually have deep entrepreneurial experience and a wealth of contacts, and can often offer important guidance and advice, but strong investor groups can oust a firm’s founder and other executives if they’re dissatisfied with the firm’s performance.

At Facebook, however, Zuckerberg owns an estimated 20 percent to 30 percent of the company, and controls three of five seats on the firm’s board of directors. That means that he’s virtually guaranteed to remain in control of the firm, regardless of what investors say. Maintaining this kind of control is unusual in a start-up, and his influence is a testament to the speed with which Facebook expanded. By the time Zuckerberg reached out to VCs, his firm was so hot that he could call the shots, giving up surprisingly little in exchange for their money.

Key Takeaways

- Facebook was founded by a nineteen-year-old college sophomore and eventual dropout.

- It is currently the largest social network in the world, boasting more than four hundred million members and usage rates that would be the envy of most media companies. The firm is now larger than MySpace in both the United States and worldwide.

- The firm’s rapid rise is the result of network effects and the speed of its adoption placed its founder in a particularly strong position when negotiating with venture firms. As a result, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg retains significant influence over the firm.

- While revenue prospects remain sketchy, some reports have valued the firm at $15 billion, based largely on an extrapolation of a Microsoft stake.

Questions and Exercises

- Who started Facebook? How old was he then? Now? How much control does the founding CEO have over his firm? Why?

- Which firms have tried to acquire Facebook? Why? What were their motivations and why did Facebook seem attractive? Do you think these bids are justified? Do you think the firm should have accepted any of the buyout offers? Why or why not?

- As of late 2007, Facebook boasted an extremely high “valuation.” How much was Facebook allegedly “worth”? What was this calculation based on?

- Why study Facebook? Who cares if it succeeds?

8.2 What’s the Big Deal?

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Recognize that Facebook’s power is allowing it to encroach on and envelop other Internet businesses.

- Understand the concept of the “dark Web” and why some feel this may one day give Facebook a source of advantage vis-à-vis Google.

- Understand the basics of Facebook’s infrastructure, and the costs required to power the effort.

The prior era’s Internet golden boy, Netscape founder Marc Andreessen, has said that Facebook is “an amazing achievement one of the most significant milestones in the technology industry.”F. Vogelstein, “How Mark Zuckerberg Turned Facebook into the Web’s Hottest Platform,” Wired, September 6, 2007. While still in his twenties, Andreessen founded Netscape, eventually selling it to AOL for over $4 billion. His second firm, Opsware, was sold to HP for $1.6 billion. He joined Facebook’s Board of Directors within months of making this comment. Why is Facebook considered such a big deal?

First there’s the growth: between December 2008 and 2009, Facebook was adding between six hundred thousand and a million users a day. It was as if every twenty-four hours, a group as big or bigger than the entire city of Boston filed into Facebook’s servers to set up new accounts. Roughly half of Facebook users visit the site every single day,D. Gage, “Facebook Claims 250 Million Users,” InformationWeek, July 16, 2009. with the majority spending fifty-five minutes or more getting their daily Facebook fix.“Facebook Facts and Figures (History and Statistics),” Website Monitoring Blog, March 17, 2010. And it seems that Mom really is on Facebook (Dad, too); users thirty-five years and older account for more than half of Facebook’s daily visitors and its fastest growing population.J. Hagel and J. S. Brown, “Life on the Edge: Learning from Facebook,” BusinessWeek, April 2, 2008; and D. Gage, “Facebook Claims 250 Million Users,” InformationWeek, July 16, 2009.

Then there’s what these users are doing on the site: Facebook isn’t just a collection of personal home pages and a place to declare your allegiance to your friends. The integrated set of Facebook services encroaches on a wide swath of established Internet businesses. Facebook has become the first-choice messaging and chat service for this generation. E-mail is for your professors, but Facebook is for friends. In photos, Google, Yahoo! and MySpace all spent millions to acquire photo sharing tools (Picasa, Flickr, and Photobucket, respectively). But Facebook is now the biggest photo-sharing site on the Web, taking in some three billion photos each month.“Facebook Facts and Figures (History and Statistics),” Website Monitoring Blog, March 17, 2010. And watch out, YouTube. Facebookers share eight million videos each month. YouTube will get you famous, but Facebook is a place most go to share clips you only want friends to see.F. Vogelstein, “Mark Zuckerberg: The Wired Interview,” Wired, June 29, 2009.

Facebook is a kingmaker, opinion catalyst, and traffic driver. While in the prior decade news stories would carry a notice saying, “Copyright, do not distribute without permission,” major news outlets today, including the New York Times, display Facebook icons alongside every copyrighted story, encouraging users to “share” the content on their profile pages via Facebook’s “Like” button, scattering it all over the Web. Like digital photos, video, and instant messaging, link sharing is Facebook’s sharp elbow to the competition. Suddenly, Facebook gets space on a page alongside Digg.com and Del.icio.us, even though those guys showed up first.

Facebook Office? Facebook rolled out the document collaboration and sharing service Docs.com in partnership with Microsoft. Facebook is also hard at work on its own e-mail system,H. Blodget, “Facebook’s Plan To Build a Real Email System and Attack Gmail Is Brilliant,” Business Insider, February 5, 2010. music service,J. Kincaid, “What Is This Mysterious Facebook Music App?” TechCrunch, February 2, 2010. and payments mechanism.R. Maher, “Facebook’s New Payment System Off to Great Start, Could Boost Revenue by $250 Million in 2010,” TBI Research, February 1, 2010. Look out, Gmail, Hotmail, Pandora, iTunes, PayPal, and Yahoo!—you may all be in Facebook’s path!

As for search, Facebook’s got designs on that, too. Google and Bing index some Facebook content, but since much of Facebook is private, accessible only among friends, this represents a massive blind spot for Google search. Sites that can’t be indexed by Google and other search engines are referred to as the dark WebInternet content that can’t be indexed by Google and other search engines.. While Facebook’s partnership with Microsoft currently offers Web search results through Bing.com, Facebook has announced its intention to offer its own search engine with real-time access to up-to-the-minute results from status updates, links, and other information made available to you by your friends. If Facebook can tie together standard Internet search with its dark Web content, this just might be enough for some to break the Google habit.

And Facebook is political—in big, regime-threatening ways. The site is considered such a powerful tool in the activist’s toolbox that China, Iran, and Syria are among nations that have, at times, attempted to block Facebook access within their borders. Egyptians have used the site to protest for democracy. Saudi women have used it to lobby for driving privileges. ABC News cosponsored U.S. presidential debates with Facebook. And Facebook cofounder Chris Hughes was even recruited by the Obama campaign to create my.barackobama.com, a social media site considered vital in the 2008 U.S. presidential victory.D. Talbot, “How Obama Really Did It,” Technology Review, September/October 2008; and E. McGirt, “How Chris Hughes Helped Launch Facebook and the Barack Obama Campaign,” Fast Company, March 17, 2009, http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/134/boy-wonder.html.

So What’s It Take to Run This Thing?

The Facebook cloudA collection of resources available for access over the Internet. (the big group of connected servers that power the site) is scattered across multiple facilities, including server farms in San Francisco, Santa Clara, and northern Virginia.A. Zeichick, “How Facebook Works,” Technology Review, July/August 2008. The innards that make up the bulk of the system aren’t that different from what you’d find on a high-end commodity workstation. Standard hard drives and eight core Intel processors—just a whole lot of them lashed together through networking and software.

Much of what powers the site is open source software (OSS)Software that is free and whose code can be accessed and potentially modified by anyone.. A good portion of the code is in PHP (a scripting language particularly well-suited for Web site development), while the databases are in MySQL (a popular open source database). Facebook also developed Cassandra, a non-SQL database project for large-scale systems that the firm has since turned over to the open source Apache Software Foundation. The object cache that holds Facebook’s frequently accessed objects is in chip-based RAM instead of on slower hard drives and is managed via an open source product called Memcache.

Other code components are written in a variety of languages, including C++, Java, Python, and Ruby, with access between these components managed by a code layer the firm calls Thrift (developed at Facebook, which was also turned over to the Apache Software Foundation). Facebook also developed its own media serving solution, called Haystack. Haystack coughs up photos 50 percent faster than more expensive, proprietary solutions, and since it’s done in-house, it saves Facebook costs that other online outlets spend on third-party content delivery networks (CDN)Systems distributed throughout the Internet (or other network) that help to improve the delivery (and hence loading) speeds of Web pages and other media, typically by spreading access across multiple sites located closer to users. Akamai is the largest CDN, helping firms like CNN and MTV quickly deliver photos, video, and other media worldwide. like Akamai. Facebook receives some fifty million requests per second,S. Gaudin, “Facebook Rolls Out Storage System to Wrangle Massive Photo Stores,” Computerworld, April 1, 2009, http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9130959/Facebook_rolls_out_storage_system_to_wrangle_massive_photo_stores. yet 95 percent of data queries can be served from a huge, distributed server cache that lives in over fifteen terabytes of RAM (objects like video and photos are stored on hard drives).A. Zeichick, “How Facebook Works,” Technology Review, July/August 2008.

Hot stuff (literally), but it’s not enough. The firm raised several hundred million dollars more in the months following the fall 2007 Microsoft deal, focused largely on expanding the firm’s server network to keep up with the crush of growth. The one hundred million dollars raised in May 2008 was “used entirely for servers.”S. Ante, “Facebook: Friends with Money,” BusinessWeek, May 9, 2008. Facebook will be buying them by the thousands for years to come. And it’ll pay a pretty penny to keep things humming. Estimates suggest the firm spends $1 million a month on electricity, another half million a month on telecommunications bandwidthTransmission rate, typically expressed as the number of bits per second that can be transmitted by a particular telecommunications mechanism., and at least fifteen million dollars a year in office and data center rental payments.A. Arrington, “Facebook Completes Rollout of Haystack to Stem Losses from Massive Photo Uploads,” TechCrunch, April 6, 2009.

Key Takeaways

- Facebook’s position as the digital center of its members’ online social lives has allowed the firm to envelop related businesses such as photo and video sharing, messaging, bookmarking, and link sharing. Facebook has opportunities to expand into other areas as well.

- Much of the site’s content is in the dark Web, unable to be indexed by Google or other search engines. Some suggest this may create an opportunity for Facebook to challenge Google in search.

- Facebook can be a vital tool for organizers—presenting itself as both opportunity and threat to those in power, and an empowering medium for those seeking to bring about change.

- Facebook’s growth requires a continued and massive infrastructure investment. The site is powered largely on commodity hardware, open source software, and proprietary code tailored to the specific needs of the service.

Questions and Exercises

- What is Facebook? How do people use the site? What do they “do” on Facebook?

- What markets has Facebook entered? What factors have allowed the firm to gain share in these markets at the expense of established firms? In what ways does it enjoy advantages that a traditional new entrant in such markets would not?

- What is the “dark Web” and why is it potentially an asset to Facebook? Why is Google threatened by Facebook’s dark Web? What firms might consider an investment in the firm, if it provided access to this asset? Do you think the dark Web is enough to draw users to a Facebook search product over Google? Why or why not?

- As Facebook grows, what kinds of investments continue to be necessary? What are the trends in these costs over time? Do you think Facebook should wait in making these investments? Why or why not?

- Investments in servers and other capital expenses typically must be depreciated over time. What does this imply about how the firm’s profitability is calculated?

- How have media attitudes toward their copyrighted content changed over the past decade? Why is Facebook a potentially significant partner for firms like the New York Times? What does the Times stand to gain by encouraging “sharing” its content? What do newspapers and others sites really mean when they encourage sites to “share?” What actually is being passed back and forth? Do you think this ultimately helps or undermines the Times and other newspaper and magazine sites? Why?

8.3 The Social Graph

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the concept of feeds, why users rebelled against Facebook feeds, and why users eventually embraced this feature.

- Recognize the two strategic resources that are most critical to Facebook’s competitive advantage and why Facebook was able to create these resources while MySpace has fallen short.

- Appreciate that while Facebook’s technology can be easily copied, barriers to sustain any new entrant are extraordinarily high, and the likelihood that a firm will win significant share from Facebook by doing the same thing is considerably remote.

At the heart of Facebook’s appeal is a concept Zuckerberg calls the social graphThe global mapping of users and organizations, and how they are connected., which refers to Facebook’s ability to collect, express, and leverage the connections between the site’s users, or as some describe it, “the global mapping of everyone and how they’re related.”A. Iskold, “Social Graph: Concepts and Issues,” ReadWriteWeb, September 12, 2007. Think of all the stuff that’s on Facebook as a node or endpoint that’s connected to other stuff. You’re connected to other users (your friends), photos about you are tagged, comments you’ve posted carry your name, you’re a member of groups, you’re connected to applications you’ve installed—Facebook links them all.A. Zeichick, “How Facebook Works,” Technology Review, July/August 2008.

While MySpace and Facebook are often mentioned in the same sentence, from their founding these sites were conceived differently. It goes beyond the fact that Facebook, with its neat, ordered user profiles, looks like a planned community compared to the garish, Vegas-like free-for-all of MySpace. MySpace was founded by musicians seeking to reach out to unknown users and make them fans. It’s no wonder the firm, with its proximity to Los Angeles and ownership by News Corporation, is viewed as more of a media company. It has cut deals to run network television shows on its site, and has even established a record label. It’s also important to note that from the start anyone could create a MySpace identity, and this open nature meant that you couldn’t always trust what you saw. Rife with bogus profiles, even News Corporation’s Rupert Murdoch has had to contend with the dozens of bogus Ruperts who have popped up on the service!L. Petrecca, “If You See These CEOs on MySpace...,” USA Today, September 25, 2006.

Facebook, however, was established in the relatively safe cocoon of American undergraduate life, and was conceived as a place where you could reinforce contacts among those who, for the most part, you already knew. The site was one of the first social networks where users actually identified themselves using their real names. If you wanted to establish that you worked for a certain firm or were a student of a particular university, you had to verify that you were legitimate via an e-mail address issued by that organization. It was this “realness” that became Facebook’s distinguishing feature—bringing along with it a degree of safety and comfort that enabled Facebook to become a true social utility and build out a solid social graph consisting of verified relationships. Since “friending” (which is a link between nodes in the social graph) required both users to approve the relationship, the network fostered an incredible amount of trust. Today, many Facebook users post their cell phone numbers and their birthdays, offer personal photos, and otherwise share information they’d never do outside their circle of friends. Because of trust, Facebook’s social graph is stronger than MySpace’s.

There is also a strong network effectAlso known as Metcalfe’s Law, or network externalities. When the value of a product or service increases as its number of users expands. to Facebook (see Chapter 6 "Understanding Network Effects"). People are attracted to the service because others they care about are more likely to be there than anywhere else online. Without the network effect Facebook wouldn’t exist. And it’s because of the network effect that another smart kid in a dorm can’t rip off Zuckerberg in any market where Facebook is the biggest fish. Even an exact copy of Facebook would be a virtual ghost town with no social graph (see Note 8.23 "It’s Not the Technology" below).

The switching costsThe cost a consumer incurs when moving from one product to another. It can involve actual money spent (e.g., buying a new product) as well as investments in time, any data loss, and so forth. for Facebook are also extremely powerful. A move to another service means recreating your entire social graph. The more time you spend on the service, the more you’ve invested in your graph and the less likely you are to move to a rival.

It’s Not the Technology

Does your firm have Facebook envy? KickApps, an eighty-person start-up in Manhattan, will give you the technology to power your own social network. All KickApps wants is a cut of the ads placed around your content. In its first two years, the site has provided the infrastructure for twenty thousand “mini Facebooks,” registering three hundred million page views a month.B. Urstadt, “The Business of Social Networks,” Technology Review, July/August 2008. NPR, ABC, AutoByTel, Harley-Davidson, and Kraft all use the service (social networks for Cheez Whiz?).

There’s also Ning, which has enabled users to create over 2.3 million mini networks organized on all sorts of topics as diverse as church groups, radio personalities, vegans, diabetes sufferers networks limited to just family members.

Or how about the offering from Agriya Infoway, based in Chennai, India? The firm will sell you Kootali, a software package that lets developers replicate Facebook’s design and features, complete with friend networks, photos, and mini-feeds. They haven’t stolen any code, but they have copied the company’s look and feel. Those with Zuckerberg ambitions can shell out the four hundred bucks for Kootali. Sites with names like Faceclub.com and Umicity.com have done just that—and gone nowhere.

Mini networks that extend the conversation (NPR) or make it easier to find other rabidly loyal product fans (Harley-Davidson) may hold a niche for some firms. And Ning is a neat way for specialized groups to quickly form in a secure environment that’s all their own (it’s just us, no “creepy friends” from the other networks). While every market has a place for its niches, none of these will grow to compete with the dominant social networks. The value isn’t in the technology; it’s in what the technology has created over time. For Facebook, it’s a huge user base that (for now at least) is not going anywhere else.

Key Takeaways

- The social graph expresses the connections between individuals and organizations.

- Trust created through user verification and friend approval requiring both parties to consent encouraged Facebook users to share more and helped the firm establish a stronger social graph than MySpace or other social networking rivals.

- Facebook’s key resources for competitive advantage are network effects and switching costs. These resources make it extremely difficult for copycat firms to steal market share from Facebook.

Questions and Exercises

- Which is bigger, Facebook or MySpace? How are these firms different? Why would a person or organization be attracted to one service over another?

- What is the social graph? Why is Facebook’s social graph considered to be stronger than the social graph available to MySpace users?

- In terms of features and utility, how are Facebook and MySpace similar? How are they different? Why would a user choose to go to one site instead of another? Are you a member of either of these sites? Both? Why? Do you feel that they are respectively pursuing lucrative markets? Why or why not? If given the opportunity, would you invest in either firm? Why or why not?

- If you were a marketer, which firm would you target for an online advertising campaign—Facebook or MySpace? Why?

- Does Facebook have to worry about copycat firms from the United States? In overseas markets? Why or why not? If Facebook has a source (or sources) of competitive advantage, explain these. If it has no advantage, discuss why.

8.4 Facebook Feeds—Ebola for Data Flows

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the concept of feeds, why users rebelled, and why users eventually embraced this feature.

- Recognize the role of feeds in viral promotions, catalyzing innovation, and supporting rapid organizing.

While the authenticity and trust offered by Facebook was critical, offering News Feeds concentrated and released value from the social graph. With feeds, each time a user performs an activity in Facebook—makes a friend, uploads a picture, joins a group—the feed blasts this information to all of your friends in a reverse chronological list that shows up right when they next log on. An individual user’s activities are also listed within a mini feed that shows up on their profile. Get a new job, move to a new city, read a great article, have a pithy quote—post it to Facebook—the feed picks it up, and the world of your Facebook friends will get an update.

Feeds are perhaps the linchpin of Facebook’s ability to strengthen and deliver user value from the social graph, but for a brief period of time it looked like feeds would kill the company. News Feeds were launched on September 5, 2006, just as many of the nation’s undergrads were arriving on campus. Feeds reflecting any Facebook activity (including changes to the relationship status) became a sort of gossip page splashed right when your friends logged in. To many, feeds were first seen as a viral blast of digital nosiness—a release of information they hadn’t consented to distribute widely.

And in a remarkable irony, user disgust over the News Feed ambush offered a whip-crack demonstration of the power and speed of the feed virus. Protest groups formed, and every student who, for example, joined a group named Students Against Facebook News Feed, had this fact blasted to their friends (along with a quick link where friends, too, could click to join the group). Hundreds of thousands of users mobilized against the firm in just twenty-four hours. It looked like Zuckerberg’s creation had turned on him, Frankenstein style.

The first official Facebook blog post on the controversy came off as a bit condescending (never a good tone to use when your customers feel that you’ve wronged them). “Calm down. Breathe. We hear you,” wrote Zuckerberg on the evening of September 5. The next post, three days after the News Feed launch, was much more contrite (“We really messed this one up,” he wrote). In the 484-word open letter, Zuckerberg apologized for the surprise, explaining how users could opt out of feeds. The tactic worked, and the controversy blew over.F. Vogelstein, “How Mark Zuckerberg Turned Facebook into the Web’s Hottest Platform,” Wired, September 6, 2007. The ability to stop personal information from flowing into the feed stream was just enough to stifle critics, and as it turns out, a lot of people really liked the feeds and found them useful. It soon became clear that if you wanted to use the Web to keep track of your social life and contacts, Facebook was the place to be. Not only did feeds not push users away, by the start of the next semester subscribers had nearly doubled!

Key Takeaways

- Facebook feeds foster the viral spread of information and activity.

- Feeds were initially unwanted by many Facebook users. Feeds themselves helped fuel online protests against the feed feature.

- Today feeds are considered one of the most vital, value-adding features to Facebook and other social networking sites.

- Users often misperceive technology and have difficulty in recognizing an effort’s value (as well as its risks). They have every right to be concerned and protective of their privacy. It is the responsibility of firms to engage users on new initiatives and to protect user privacy. Failure to do so risks backlash.

Questions and Exercises

- What is the “linchpin” of Facebook’s ability to strengthen and deliver user-value from the social graph?

- How did users first react to feeds? What could Facebook have done to better manage the launch?

- How do you feel about Facebook feeds? Have you ever been disturbed by information about you or someone else that has appeared in the feed? Did this prompt action? Why or why not?

- Visit Facebook and experiment with privacy settings. What kinds of control do you have over feeds and data sharing? Is this enough to set your mind at ease? Did you know these settings existed before being prompted to investigate features?

- What other Web sites are leveraging features that mimic Facebook feeds? Do you think these efforts are successful or not? Why?

8.5 Facebook as a Platform

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand how Facebook created a platform and the potential value this offers the firm.

- Recognize that running a platform also presents a host of challenges to the platform operator.

In May 2007, Facebook followed News Feeds with another initiative that set it head and shoulders above its competition. At the firm’s first f8 (pronounced “fate”) Developers Conference, Mark Zuckerberg stood on stage and announced that he was opening up the screen real estate on Facebook to other application developers. Facebook published a set of application programming interfaces (APIs)Programming hooks, or guidelines, published by firms that tell other programs how to get a service to perform a task such as send or receive data. For example, Amazon.com provides APIs to let developers write their own applications and Websites that can send the firm orders. that specified how programs could be written to run within and interact with Facebook. Now any programmer could write an application that would run inside a user’s profile. Geeks of the world, Facebook’s user base could be yours! Just write something good.

Developers could charge for their wares, offer them for free, and even run ads. And Facebook let developers keep what they made (Facebook does revenue share with app vendors for some services, such as the Facebook Credits payment service, mentioned later). This was a key distinction; MySpace initially restricted developer revenue on the few products designed to run on their site, at times even blocking some applications. The choice was clear, and developers flocked to Facebook.

To promote the new apps, Facebook would run an Applications area on the site where users could browse offerings. Even better, News Feed was a viral injection that spread the word each time an application was installed. Your best friend just put up a slide show app? Maybe you’ll check it out, too. The predictions of $1 billion in social network ad spending were geek catnip, and legions of programmers came calling. Apps could be cobbled together on the quick, feeds made them spread like wildfire, and the early movers offered adoption rates never before seen by small groups of software developers. People began speaking of the Facebook Economy. Facebook was considered a platform. Some compared it to the next Windows, Zuckerberg the next Gates (hey, they both dropped out of Harvard, right?).

And each application potentially added more value and features to the site without Facebook lifting a finger. The initial event launched with sixty-five developer partners and eighty-five applications. There were some missteps along the way. Some applications were accused of spamming friends with invites to install them. There were also security concerns and apps that violated the intellectual property of other firms (see the “Scrabulous” sidebar below), but Facebook worked to quickly remove errant apps, improve the system, and encourage developers. Just one year in, Facebook had marshaled the efforts of some four hundred thousand developers and entrepreneurs, twenty-four thousand applications had been built for the platform, 140 new apps were being added each day, and 95 percent of Facebook members had installed at least one Facebook application. As Sarah Lacy, author of Once You’re Lucky, Twice You’re Good, put it, “with one masterstroke, Zuck had mobilized all of Silicon Valley to innovate for him.”

With feeds to spread the word, Facebook was starting to look like the first place to go to launch an online innovation. Skip the Web, bring it to Zuckerberg’s site first. Consider iLike: within the first three months, the firm saw installs of its Facebook app explode to seven million, more than doubling the number of users the firm was able to attract through the Web site it introduced the previous year. ILike became so cool that by September, platinum rocker KT Tunstall was debuting tracks through the Facebook service. A programmer named Mark Pincus wrote a Texas hold ’em game at his kitchen table.J. Guynn, “A Software Industry @ Facebook,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 2007. Today his social gaming firm, Zynga, is a powerhouse—a profitable firm with over three dozen apps, over 230 million users,D. MacMillan, “Zynga Enlarges Its War Chest,” BusinessWeek, December 17, 2009. and more than $600 million in annual revenue.M. Learmonth and A. Klaasen, “Facebook Apps Will Make More Money Than Facebook in 2009,” Silicon Alley Insider, May 18, 2009. Some of Zynga’s revenues come from apps that run on MySpace or other networks, too. Also see N. Carolson, “The Profitable, $100 Million-a-Year Startup You’ve Never Heard Of,” Business Insider, July 27, 2009; and N. Carlson and K. Angelova, “Chart of the Day: FarmVille-Maker Zynga’s Revenues Reach $600 Million, Fueled by Social Obligations,” April 26, 2010. Zynga games include MafiaWars, Vampires, and the wildly successful FarmVille, which boasts some twenty times the number of actual farms in the United States. App firm Slide (started by PayPal cofounder Max Levchin) scored investments from Legg Mason, and Fidelity pegged the firm’s value at $500 million.J. Hempel and M. Copeland, “Are These Widgets Worth Half a Billion?” Fortune, March 25, 2008. Playfish, the U.K. social gaming firm behind the Facebook hits Pet Society and Restaurant City, was snapped up by Electronic Arts for $300 million with another $100 million due if the unit hits performance targets. Lee Lorenzen, founder of Altura Ventures, an investment firm exclusively targeting firms creating Facebook apps, said, “Facebook is God’s gift to developers. Never has the path from a good idea to millions of users been shorter.”J. Guynn, “A Software Industry @ Facebook,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 2007.

I Majored in Facebook

Once Facebook became a platform, Stanford professor BJ Fogg thought it would be a great environment for a programming class. In ten weeks his seventy-three students built a series of applications that collectively received over sixteen million installs. By the final week of class, several applications developed by students, including KissMe, Send Hotness, and Perfect Match, had received millions of users, and class apps collectively generated more than half a million dollars in ad revenue. At least three companies were formed from the course.

But legitimate questions remain. Are Facebook apps really a big deal? Just how important will apps be to adding sustained value within Facebook? And how will firms leverage the Facebook framework to extract their own value? A chart from FlowingData showed the top category, Just for Fun, was larger than the next four categories combined. That suggests that a lot of applications are faddish time wasters. Yes, there is experimentation beyond virtual Zombie Bites. Visa has created a small business network on Facebook (Facebook had some eighty thousand small businesses online at the time of Visa’s launch). Educational software firm Blackboard offered an application that will post data to Facebook pages as soon as there are updates to someone’s Blackboard account (new courses, whether assignments or grades have been posted, etc.). We’re still a long way from Facebook as a Windows rival, but the platform helped push Facebook to number one, and it continues to deliver quirky fun (and then some) supplied by thousands of developers off its payroll.

Scrabulous

Rajat and Jayant Agarwalla, two brothers in Kolkata, India, who run a modest software development company, decided to write a Scrabble clone as a Facebook application. The app, named Scrabulous, was social—users could invite friends to play, or they could search for new players looking for an opponent. Their application was a smash, snagging three million registered users and seven hundred thousand players a day after just a few months. Scrabulous was featured in PC World’s 100 best products of 2008, received coverage in the New York Times, Newsweek, and Wired, and was pulling in about twenty-five thousand dollars a month from online advertising. Way to go, little guys!H. Timmons, “Online Scrabble Craze Leaves Game Sellers at Loss for Words,” New York Times, March 2, 2008.

There is only one problem: the Agarwalla brothers didn’t have the legal rights to Scrabble, and it was apparent to anyone that from the name to the tiles to the scoring—this was a direct rip-off of the well-known board game. Hasbro owns the copyright to Scrabble in the United States and Canada; Mattel owns it everywhere else. Thousands of fans joined Facebook groups with names like “Save Scrabulous” and “Please God, I Have So Little: Don’t Take Scrabulous, Too.” Users in some protest groups pledged never to buy Hasbro games if Scrabulous was stopped. Even if the firms wanted to succumb to pressure and let the Agarwalla brothers continue, they couldn’t. Both Electronic Arts and RealNetworks have contracted with the firms to create online versions of the game.

While the Facebook Scrabulous app is long gone, the tale shows just one of the challenges of creating a platform. In addition to copyright violations, app makers have crafted apps that annoy, raise privacy and security concerns, purvey pornography, or otherwise step over the boundaries of good taste. Firms from Facebook to Apple (through its iTunes Store) have struggled to find the right mix of monitoring, protection, and approval while avoiding cries of censorship.

Key Takeaways

- Facebook’s platform allows the firm to further leverage the network effect. Developers creating applications create complementary benefits that have the potential to add value to Facebook beyond what the firm itself provides to its users.

- There is no revenue-sharing mandate among platform partners—whatever an application makes can be kept by its developers (although Facebook does provide some services via revenue sharing, such as Facebook Credits).

- Most Facebook applications are focused on entertainment. The true, durable, long-term value of Facebook’s platform remains to be seen.

- Despite this, some estimates claim Facebook platform developers earned more than Facebook itself in 2009.

- Running a platform can be challenging. Copyright, security, appropriateness, free speech tensions, efforts that tarnish platform operator brands, privacy, and the potential for competition with partners, all can make platform management more complex than simply creating a set of standards and releasing this to the public.

Questions and Exercises

- Why did more developers prefer to write apps for Facebook than for MySpace?

- What competitive asset does the application platform initiative help Facebook strengthen? For example, how do apps make Facebook stronger when compared to rivals?

- What’s Scrabulous? Did the developers make money? What happened to the firm and why?

- Have you used Facebook apps? Which are your favorites? What makes them successful?

- Leverage your experience or conduct additional research—are there developers who you feel have abused the Facebook app network? Why? What is Facebook’s responsibility (if any) to control such abuse?

- How do most app developers make money? Have you ever helped a Facebook app developer earn money? How or why not?

- How do Facebook app revenue opportunities differ from those leveraged by a large portion of iTunes Store apps?

8.6 Advertising and Social Networks: A Work in Progress

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the differences in the Facebook and Google ad models.

- Explain the Hunt versus Hike metaphor, contrast the relative success of ad performance on search compared to social networks, and understand the factors behind the latter’s struggles.

- Recognize how firms are leveraging social networks for brand and product engagement, be able to provide examples of successful efforts, and give reasons why such engagement is difficult to achieve.

If Facebook is going to continue to give away its services for free, it needs to make money somehow. Right now the bulk of revenue comes from advertising. Fortunately for the firm, online advertising is hot. For years, online advertising has been the only major media category that has seen an increase in spending (see Chapter 14 "Google: Search, Online Advertising, and Beyond"). Firms spend more advertising online than they do on radio and magazine ads, and the Internet will soon beat out spending on cable TV.M. Sweeney, “Internet Ad Spending Will Overtake Television in 2009,” Guardian, May 19, 2008; and T. Wayne, “A Milestone for Internet Ad Revenue,” New York Times, April 25, 2010. But not all Internet advertising is created equal. And there are signs that social networking sites are struggling to find the right ad model.

Google founder Sergey Brin sums up this frustration, saying, “I don’t think we have the killer best way to advertise and monetize social networks yet,” that social networking ad inventory as a whole was proving problematic and that the “monetization work we were doing [in social media] didn’t pan out as well as we had hoped.”“Everywhere and Nowhere,” Economist, March 19, 2008. When Google ad partner Fox Interactive Media (the News Corporation division that contains MySpace) announced that revenue would fall $100 million short of projections, News Corporation’s stock tumbled 5 percent, analysts downgraded the company, and the firm’s chief revenue officer was dismissed.B. Stelter, “MySpace Might Have Friends, but It Wants Ad Money,” New York Times, June 16, 2008.

Why aren’t social networks having the success of Google and other sites? Problems advertising on these sites include content adjacencyConcern that an advertisement will run near offensive material, embarrassing an advertiser and/or degrading their products or brands., and user attention. The content adjacency problem refers to concern over where a firm’s advertisements will run. Consider all of the questionable titles in social networking news groups. Do advertisers really want their ads running alongside conversations that are racy, offensive, illegal, or that may even mock their products? This potential juxtaposition is a major problem with any site offering ads adjacent to free-form social media. Summing up industry wariness, one P&G manager said, “What in heaven’s name made you think you could monetize the real estate in which somebody is breaking up with their girlfriend?”B. Stone, “Facebook Aims to Extends Its Reach across Web,” New York Times, December 1, 2008. An IDC report suggests that it’s because of content adjacency that “brand advertisers largely consider user-generated content as low-quality, brand-unsafe inventory” for running ads.R. Stross, “Advertisers Face Hurdles on Social Networking Sites,” New York Times, December 14, 2008.

Now let’s look at the user attention problem.

Attention Challenges: The Hunt Versus The Hike

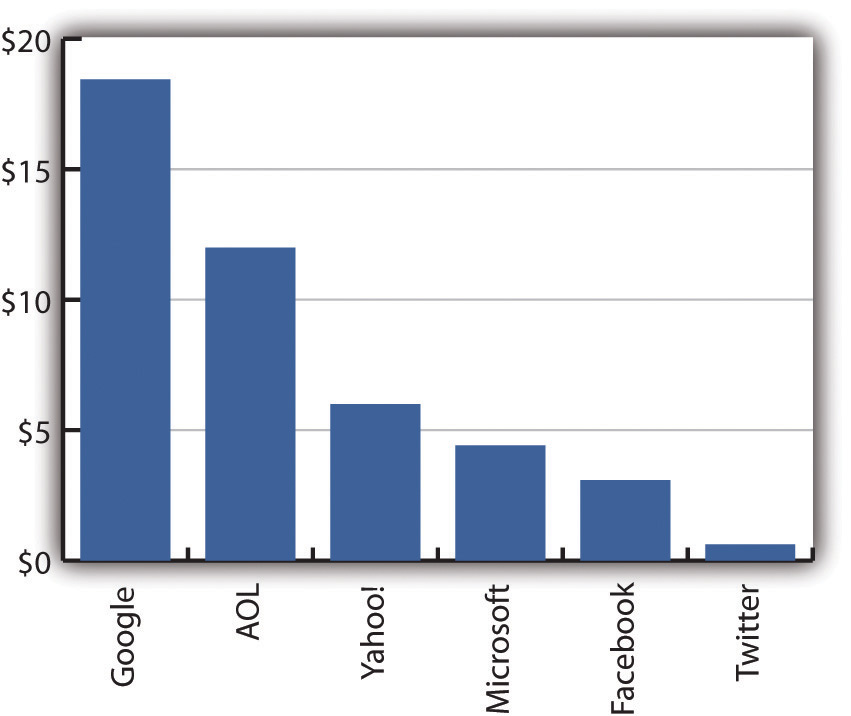

In terms of revenue model, Facebook is radically different from Google and the hot-growth category of search advertising. Users of Google and other search sites are on a hunt—a task-oriented expedition to collect information that will drive a specific action. Search users want to learn something, buy something, research a problem, or get a question answered. To the extent that the hunt overlaps with ads, it works. Just searched on a medical term? Google will show you an ad from a drug company. Looking for a toy? You’ll see Google ads from eBay sellers and other online shops. Type in a vacation destination and you get a long list of ads from travel providers aggressively courting your spending. Even better, Google only charges text advertisers when a user clicks through. No clicks? The ad runs at no cost to the firm. From a return on investment perspective, this is extraordinarily efficient. How often do users click on Google ads? Enough for this to be the single most profitable activity among any Internet firm. In 2009, Google revenue totaled nearly $24 billion. Profits exceeded $6.5 billion, almost all of this from pay-per-click ads (see Chapter 14 "Google: Search, Online Advertising, and Beyond" for more details).

While users go to Google to hunt, they go to Facebook as if they were going on a hike—they have a rough idea of what they’ll encounter, but they’re there to explore and look around, enjoy the sights (or site). They’ve usually allocated time for fun and they don’t want to leave the terrain when they’re having conversations, looking at photos or videos, and checking out updates from friends.

These usage patterns are reflected in click-through rates. Google users click on ads around 2 percent of the time (and at a much higher rate when searching for product information). At Facebook, click-throughs are about 0.04 percent.B. Urstadt, “The Business of Social Networks,” Technology Review, July/August 2008. Rates quoted in this piece seem high, but a large discrepancy between site rates holds across reported data.

Most banner ads don’t charge per click but rather CPMCost per thousand impressions (the M representing the roman numeral for one thousand). (cost per thousand) impressionsEach time an ad is served to a user for viewing. (each time an ad appears on someone’s screen). But Facebook banner ads performed so poorly that the firm pulled them in early 2010.C. McCarthy, “More Social, Please: Facebook Nixes Banner Ads,” CNET, February 5, 2010. Lookery, a one-time ad network that bought ad space on Facebook in bulk, had been reselling inventory at a CPM of 7.5 cents (note that Facebook does offer advertisers pay-per-click as well as impression-based, or CPM, options). Even Facebook ads with a bit of targeting weren’t garnering much (Facebook’s Social Ads, which allow advertisers to target users according to location and age, have a floor price of fifteen cents CPM).B. Urstadt, “The Business of Social Networks,” Technology Review, July/August 2008; J. Hempel, “Finding Cracks in Facebook,” Fortune, May 13, 2008; and E. Schonfeld, “Are Facebook Ads Going to Zero? Lookery Lowers Its Guarantee to 7.5-cent CMPs,” TechCrunch, July 22, 2008. Other social networks also suffered. In 2008, MySpace lowered its banner ad rate from $3.25 CPM to less than two dollars. By contrast, information and news-oriented sites do much better, particularly if these sites draw in a valuable and highly targeted audience. The social networking blog Mashable has CPM rates ranging between seven and thirty-three dollars. Technology Review magazine boasts a CPM of seventy dollars. TechTarget, a Web publisher focusing on technology professionals, has been able to command CPM rates of one hundred dollars and above (an ad inventory that valuable helped the firm go public in 2007).

Getting Creative with Promotions: Does It Work?

Facebook and other social networks are still learning what works. Ad inventory displayed on high-traffic home pages have garnered big bucks for firms like Yahoo! With Facebook offering advertisers greater audience reach than most network television programs, there’s little reason to suggest that chunks of this business won’t eventually flow to the social networks. But even more interesting is how Facebook and widget sites have begun to experiment with relatively new forms of advertising. Many feel that Facebook has a unique opportunity to get consumers to engage with their brand, and some initial experiments point where this may be heading.

Many firms have been leveraging so-called engagement adsPromotion technique popular with social media that attempts to get consumers to interact with an ad, then shares that action with friends. by making their products part of the Facebook fun. Using an engagement ad, a firm can set up a promotion where a user can do things such as “Like” or become a fan of a brand, RSVP to an event and invite others, watch and comment on a video and see what your friends have to say, send a “virtual gift” with a personal message, or answer a question in a poll. The viral nature of Facebook allows actions to flow back into the news feed and spread among friends.

COO Sheryl Sandberg discussed Ben & Jerry’s promotion for the ice cream chain’s free cone day event. To promote the upcoming event, Ben & Jerry’s initially contracted to make two hundred and fifty thousand “gift cones” available to Facebook users; they could click on little icons that would gift a cone icon to a friend, and that would show up in their profile. Within a couple of hours, customers had sent all two hundred and fifty thousand virtual cones. Delighted, Ben & Jerry’s bought another two hundred and fifty thousand cones. Within eleven hours, half a million people had sent cones, many making plans with Facebook friends to attend the real free cone day. The day of the Facebook promotion, Ben & Jerry’s Web site registered fifty-three million impressions, as users searched for store locations and wrote about their favorite flavors.Q. Hardy, “Facebook Thinks Outside Boxes,” Forbes, May 28, 2008. The campaign dovetailed with everything Facebook was good at: it was viral, generating enthusiasm for a promotional event and even prompting scheduling.

In other promotions, Honda gave away three quarters of a million hearts during a Valentine’s Day promo,S. Sandberg, “Sheryl Sandberg on Facebook’s Future,” BusinessWeek, April 8, 2009. and the Dr. Pepper Snapple Group offered two hundred and fifty thousand virtual Sunkist sodas, which earned the firm one hundred thirty million brand impressions in twenty-two hours. Says Sunkist’s brand manager, “A Super Bowl ad, if you compare it, would have generated somewhere between six to seven million.”E. Wong, “Ben & Jerry’s, Sunkist, Indy Jones Unwrap Facebook’s ‘Gift of Gab,’” Brandweek, June 1, 2008.

Facebook, Help Get Me a Job!

The papers are filled with stories about employers scouring Facebook for dirt on potential hires. But one creative job seeker turned the tables and used Facebook to make it easier for firms to find him. Recent MBA graduate Eric Barker, a talented former screenwriter with experience in the film and gaming industry, bought ads promoting himself on Facebook, setting them up to run only on the screens of users identified as coming from firms he’d like to work for. In this way, someone Facebook identified as being from Microsoft would see an ad from Eric declaring “I Want to Be at Microsoft” along with an offer to click and learn more. The cost to run the ads was usually less than $5 a day. Said Barker, “I could control my bid price and set a cap on my daily spend. Starbucks put a bigger dent in my wallet than promoting myself online.” The ads got tens of thousands of impressions, hundreds of clicks, and dozens of people called offering assistance. Today, Eric Barker is gainfully employed at a “dream job” in the video game industry.Eric is a former student of mine. His story has been covered by many publications, including J. Zappe, “MBA Grad Seeks Job with Microsoft; Posts Ad on Facebook,” ERE.net, May 27, 2009; G. Sentementes, “‘Hire Me’ Nation: Using the Web & Social Media to Get a Job,” Baltimore Sun, July 15, 2009; and E. Liebert, Facebook Fairytales (New York: Skyhorse, 2010).

Figure 8.1

Eric Barker used Facebook to advertise himself to prospective employers.

Of course, even with this business, Facebook may find that it competes with widget makers. Unlike Apple’s App Store (where much of developer-earned revenue comes from selling apps), the vast majority of Facebook apps are free and supported by ads. That means Facebook and its app providers are both running at a finite pot of advertising dollars. Slide’s Facebook apps have attracted top-tier advertisers, such as Coke and Paramount Pictures—a group Facebook regularly courts as well. By some estimates, in 2009, Facebook app developers took in well over half a billion dollars—exceeding Facebook’s own haul.M. Learmonth and A. Klaasen, “Facebook Apps Will Make More Money Than Facebook in 2009,” Silicon Alley Insider, May 18, 2009. And there’s controversy. Zynga was skewered in the press when some of its partners were accused of scamming users into signing up for subscriptions or installing unwanted software in exchange for game credits (Zynga has since taken steps to screen partners and improve transparency).M. Arrington, “Zynga Takes Steps to Remove Scams from Games,” TechCrunch, November 2, 2009.

While these efforts might be innovative, are they even effective? Some of these programs are considered successes; others, not so much. Jupiter Research surveyed marketers trying to create a viral impact online and found that only about 15 percent of these efforts actually caught on with consumers.M. Cowan, “Marketers Struggle to Get Social,” Reuters, June 19, 2008, http://www.reuters.com/news/video?videoId=84894. While the Ben & Jerry’s gift cones were used up quickly, a visit to Facebook in the weeks after this campaign saw CareerBuilder, Wide Eye Caffeinated Spirits, and Coors Light icons lingering days after their first appearance. Brands seeking to deploy their own applications in Facebook have also struggled. New Media Age reported that applications rolled out by top brands such as MTV, Warner Bros., and Woolworths were found to have as little as five daily users. Congestion may be setting in for all but the most innovative applications, as standing out in a crowd of over 550,000 applications becomes increasingly difficult.Facebook Press Room, Statistics, April 29, 2010, http://www.facebook.com/press/info.php?statistics.

Consumer products giant P&G has been relentlessly experimenting with leveraging social networks for brand engagement, but the results show what a tough slog this can be. The firm did garner fourteen thousand Facebook “fans” for its Crest Whitestrips product, but those fans were earned while giving away free movie tickets and other promos. The New York Times quipped that with those kinds of incentives, “a hemorrhoid cream” could have attracted a similar group of “fans.” When the giveaways stopped, thousands promptly “unfanned” Whitestrips. Results for Procter & Gamble’s “2X Ultra Tide” fan page were also pretty grim. P&G tried offbeat appeals for customer-brand bonding, including asking Facebookers to post “their favorite places to enjoy stain-making moments.” But a check eleven months after launch had garnered just eighteen submissions, two from P&G, two from staffers at spoof news site The Onion, and a bunch of short posts such as “Tidealicious!”R. Stross, “Advertisers Face Hurdles on Social Networking Sites,” New York Times, December 14, 2008.

Efforts around engagement opportunities like events (Ben & Jerry’s) or products consumers are anxious to identify themselves with (a band or a movie) may have more success than trying to promote consumer goods that otherwise offer little allegiance, but efforts are so new that metrics are scarce, impact is tough to gauge, and best practices are still unclear.

Key Takeaways

- Content adjacency and user attention make social networking ads less attractive than search and professionally produced content sites.

- Google enjoys significantly higher click-through rates than Facebook.

- Display ads are often charged based on impression. Social networks also offer lower CPM rates than many other, more targeted Web sites.

- Social networking has been difficult to monetize, as users are online to engage friends, not to hunt for products or be drawn away by clicks.

- Many firms have begun to experiment with engagement ads. While there have been some successes, engagement campaigns often haven’t yielded significant results.

Questions and Exercises

- How are most display ads billed? What acronym is used to describe pricing of most display ads?

- How are most text ads billed?

- Contrast Facebook and Google click-through rates. Contrast Facebook CPMs with CPMs at professional content sites. Why the discrepancy?

- What is the content adjacency problem? Search for examples of firms that have experienced embracement due to content adjacency—describe them, why they occurred, and if site operators could have done something to reduce the likelihood these issues could have occurred.

- What kinds of Web sites are most susceptible to content adjacency? Are news sites? Why or why not? What sorts of technical features might act as breeding grounds for content adjacency problems?

- If a firm removed user content because it was offensive to an advertiser, what kinds of problems might this create? When (if ever) should a firm remove or take down user content?

- How are firms attempting to leverage social networks for brand and product engagement?

- What are the challenges that social networking sites face when trying to woo advertisers?

- Describe an innovative marketing campaign that has leveraged Facebook or other social networking sites. What factors made this campaign work? Are all firms likely to have this sort of success? Why or why not?

- Have advertisers ever targeted you when displaying ads on Facebook? How were you targeted? What did you think of the effort?

8.7 Privacy Peril: Beacon and the TOS Debacle

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the difference between opt-in and opt-out efforts.

- Recognize how user issues and procedural implementation can derail even well-intentioned information systems efforts.

- Recognize the risks in being a pioneer associated with new media efforts, and understand how missteps led to Facebook and its partners being embarrassed (and in some cases sued) by Beacon’s design and rollout issues.

Conventional advertising may grow into a great business for Facebook, but the firm was clearly sitting on something that was unconventional compared to prior generations of Web services. Could the energy and virulent nature of social networks be harnessed to offer truly useful, consumer information to its users? Word of mouth is considered the most persuasive (and valuable) form of marketing,V. Kumar, J. Andrew Petersen, and Robert Leone, “How Valuable Is Word of Mouth?” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 10 (October 2007): 139–46. and Facebook was a giant word of mouth machine. What if the firm worked with vendors and grabbed consumer activity at the point of purchase to put into the News Feed and post to a user’s profile? If you rented a video, bought a cool product, or dropped something in your wish list, your buddies could get a heads-up and they might ask you about it. The person being asked feels like an expert, the person with the question gets a frank opinion, and the vendor providing the data just might get another sale. It looked like a home run.

This effort, named Beacon, was announced in November 2007. Some forty e-commerce sites signed up, including Blockbuster, Fandango, eBay, Travelocity, Zappos, and the New York Times. Zuckerberg was so confident of the effort that he stood before a group of Madison Avenue ad executives and declared that Beacon would represent a “once-in-a-hundred-years” fundamental change in the way media works.

Like News Feeds, user reaction was swift and brutal. The commercial activity of Facebook users began showing up without their consent. The biggest problem with Beacon was that it was “opt-out” instead of “opt-in.” Facebook (and its partners) assumed users would agree to sharing data in their feeds. A pop-up box did appear briefly on most sites supporting Beacon, but it disappeared after a few seconds.E. Nakashima, “Feeling Betrayed, Facebook Users Force Site to Honor Their Privacy,” Washington Post, November 30, 2007. Many users, blind to these sorts of alerts, either clicked through or ignored the warnings. And well...there are some purchases you might not want to broadcast to the world.

“Facebook Ruins Christmas for Everyone!” screamed one headline from MSNBC.com. Another from U.S. News and World Report read “How Facebook Stole Christmas.” The Washington Post ran the story of Sean Lane, a twenty-eight-year-old tech support worker from Waltham, Massachusetts, who got a message from his wife just two hours after he bought a ring on Overstock.com. “Who is this ring for?” she wanted to know. Facebook had not only posted a feed that her husband had bought the ring, but also that he got it for a 51 percent discount! Overstock quickly announced that it was halting participation in Beacon until Facebook changed its practice to opt in.E. Nakashima, “Feeling Betrayed, Facebook Users Force Site to Honor Their Privacy,” Washington Post, November 30, 2007.

MoveOn.org started a Facebook group and online petition protesting Beacon. The Center for Digital Democracy and the U.S. Public Interest Research Group asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate Facebook’s advertising programs. And a Dallas woman sued Blockbuster for violating the Video Privacy Protection Act (a 1998 U.S. law prohibiting unauthorized access to video store rental records).

To Facebook’s credit, the firm acted swiftly. Beacon was switched to an opt-in system, where user consent must be given before partner data is sent to the feed. Zuckerberg would later say regarding Beacon: “We’ve made a lot of mistakes building this feature, but we’ve made even more with how we’ve handled them. We simply did a bad job with this release, and I apologize for it.”C. McCarthy, “Facebook’s Zuckerberg: ‘We Simply Did a Bad Job’ Handling Beacon,” CNET, December 5, 2007. Beacon was eventually shut down and $9.5 million was donated to various privacy groups as part of its legal settlement.J. Brodkin, “Facebook Shuts Down Beacon Program, Donates $9.5 Million to Settle Lawsuit,” NetworkWorld, December 8, 2009. Despite the Beacon fiasco, new users continued to flock to the site, and loyal users stuck with Zuck. Perhaps a bigger problem was that many of those forty A-list e-commerce sites that took a gamble with Facebook now had their names associated with a privacy screw-up that made headlines worldwide. A manager so burned isn’t likely to sign up first for the next round of experimentation.

From the Prada example in Chapter 3 "Zara: Fast Fashion from Savvy Systems" we learned that savvy managers look beyond technology and consider complete information systems—not just the hardware and software of technology but also the interactions among the data, people, and procedures that make up (and are impacted by) information systems. Beacon’s failure is a cautionary tale of what can go wrong if users fail to broadly consider the impact and implications of an information system on all those it can touch. Technology’s reach is often farther, wider, and more significantly impactful than we originally expect.

Reputation Damage and Increased Scrutiny—The Facebook TOS Debacle

Facebook also suffered damage to its reputation, brand, and credibility, further reinforcing perceptions that the company acts brazenly, without considering user needs, and is fast and loose on privacy and user notification. Facebook worked through the feeds outrage, eventually convincing users of the benefits of feeds. But Beacon was a fiasco. And now users, the media, and watchdogs were on the alert.

When the firm modified its terms of service (TOS) policy in Spring 2009, the uproar was immediate. As a cover story in New York magazine summed it up, Facebook’s new TOS appeared to state, “We can do anything we want with your content, forever,” even if a user deletes their account and leaves the service.V. Grigoriadis, “Do You Own Facebook? Or Does Facebook Own You?” New York, April 5, 2009. Yet another privacy backlash!

Activists organized, the press crafted juicy, attention-grabbing headlines, and the firm was forced once again to backtrack. But here’s where others can learn from Facebook’s missteps and response. The firm was contrite and reached out to explain and engage users. The old TOS were reinstated, and the firm posted a proposed new version that gave the firm broad latitude in leveraging user content without claiming ownership. And the firm renounced the right to use this content if a user closed their Facebook account. This new TOS was offered in a way that solicited user comments, and it was submitted to a community vote, considered binding if 30 percent of Facebook users participated. Zuckerberg’s move appeared to have turned Facebook into a democracy and helped empower users to determine the firm’s next step.

Despite the uproar, only about 1 percent of Facebook users eventually voted on the measure, but the 74 percent to 26 percent ruling in favor of the change gave Facebook some cover to move forward.J. Smith, “Facebook TOS Voting Concludes, Users Vote for New Revised Documents,” Inside Facebook, April 23, 2009. This event also demonstrates that a tempest can be generated by a relatively small number of passionate users. Firms ignore the vocal and influential at their own peril!

In Facebook’s defense, the broad TOS was probably more a form of legal protection than any nefarious attempt to exploit all user posts ad infinitum. The U.S. legal environment does require that explicit terms be defined and communicated to users, even if these are tough for laypeople to understand. But a “trust us” attitude toward user data doesn’t work, particularly for a firm considered to have committed ham-handed gaffes in the past. Managers must learn from the freewheeling Facebook community. In the era of social media, your actions are now subject to immediate and sustained review. Violate the public trust and expect the equivalent of a high-powered investigative microscope examining your every move, and a very public airing of the findings.

Key Takeaways

- Word of mouth is the most powerful method for promoting products and services, and Beacon was conceived as a giant word-of-mouth machine with win-win benefits for firms, recommenders, recommendation recipients, and Facebook.

- Beacon failed because it was an opt-out system that was not thoroughly tested beforehand, and because user behavior, expectations, and system procedures were not completely taken into account.

- Partners associated with the rapidly rolled out, poorly conceived, and untested effort were embarrassed. Several faced legal action.

- Facebook also reinforced negative perceptions regarding the firm’s attitudes toward users, notifications, and their privacy. This attitude only served to focus a continued spotlight on the firm’s efforts, and users became even less forgiving.

- Activists and the media were merciless in criticizing the firm’s Terms of Service changes. Facebook’s democratizing efforts demonstrate lessons other organizations can learn from, regarding user scrutiny, public reaction, and stakeholder engagement.

Questions and Exercises

- What is Beacon? Why was it initially thought to be a good idea? What were the benefits to firm partners, recommenders, recommendation recipients, and Facebook? Who were Beacon’s partners and what did they seek to gain through the effort?

- Describe “the biggest problem with Beacon?” Would you use Beacon? Why or why not?

- How might Facebook and its partners have avoided the problems with Beacon? Could the effort be restructured while still delivering on its initial promise? Why or why not?

- Beacon shows the risk in being a pioneer—are there risks in being too cautious and not pioneering with innovative, ground-floor marketing efforts? What kinds of benefits might a firm miss out on? Is there a disadvantage in being late to the party with these efforts, as well? Why or why not?

- Why do you think Facebook changed its Terms of Service? Did these changes concern you? Were users right to rebel? What could Facebook have done to avoid the problem? Did Facebook do a good job in follow-up? How would you advise Facebook to apply lessons learned form the TOS controversy?

8.8 Predators and Privacy

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the extent and scope of the predator problem on online social networks.

- Recognize the steps firms are taking to proactively engage and limit these problems.

While spoiling Christmas is bad, sexual predators are far worse, and in October 2007, Facebook became an investigation target. Officials from the New York State Attorney General’s office had posed as teenagers on Facebook and received sexual advances. Complaints to the service from investigators posing as parents were also not immediately addressed. These were troubling developments for a firm that prided itself on trust and authenticity.

In a 2008 agreement with forty-nine states, Facebook offered aggressive programs, many of which put it in line with MySpace. MySpace had become known as a lair for predators, and after months of highly publicized tragic incidents, the firm had become very aggressive about protecting minors. To get a sense of the scope of the problem, consider that MySpace claimed that it had found and deleted some twenty-nine thousand accounts from its site after comparing profiles against a database of convicted sex offenders.“Facebook Targets China, World’s Biggest Web Market,” Reuters, June 20, 2008. Following MySpace’s lead, Facebook agreed to respond to complaints about inappropriate content within twenty-four hours and to allow an independent examiner to monitor how it handles complaints. The firm imposed age-locking restrictions on profiles, reviewing any attempt by someone under the age of eighteen to change their date of birth. Profiles of minors were no longer searchable. The site agreed to automatically send a warning message when a child is at risk of revealing personal information to an unknown adult. And links to explicit material, the most offensive Facebook groups, and any material related to cyberbullying were banned.

Busted on Facebook

Chapter 7 "Peer Production, Social Media, and Web 2.0" warned that your digital life will linger forever, and that employers are increasingly plumbing the depths of virtual communities in order to get a sense of job candidates. And it’s not just employers. Sleuths at universities and police departments have begun looking to Facebook for evidence of malfeasance. Oxford University fined graduating students more than £10,000 for their post-exam celebrations, evidence of which was picked up from Facebook. Police throughout the United States have made underage drinking busts and issued graffiti warnings based on Facebook photos, too. Beware—the Web knows!

Key Takeaways

- Thousands of sex offenders and other miscreants have been discovered on MySpace, Facebook, and other social networks. They are a legitimate risk to the community and they harm otherwise valuable services.

- A combination of firm policies, computerized and human monitoring, aggressive reporting and follow-up, and engagement with authorities can reduce online predator risks.