This is “Satellite Imagery and Aerial Photography”, section 4.3 from the book Geographic Information System Basics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.3 Satellite Imagery and Aerial Photography

Learning Objective

- The objective of this section is to understand how satellite imagery and aerial photography are implemented in GIS applications.

A wide variety of satellite imagery and aerial photography is available for use in geographic information systems (GISs). Although these products are basically raster graphics, they are substantively different in their usage within a GIS. Satellite imagery and aerial photography provide important contextual information for a GIS and are often used to conduct heads-up digitizing (Chapter 5 "Geospatial Data Management", Section 5.1.4 "Secondary Data Capture") whereby features from the image are converted into vector datasets.

Satellite Imagery

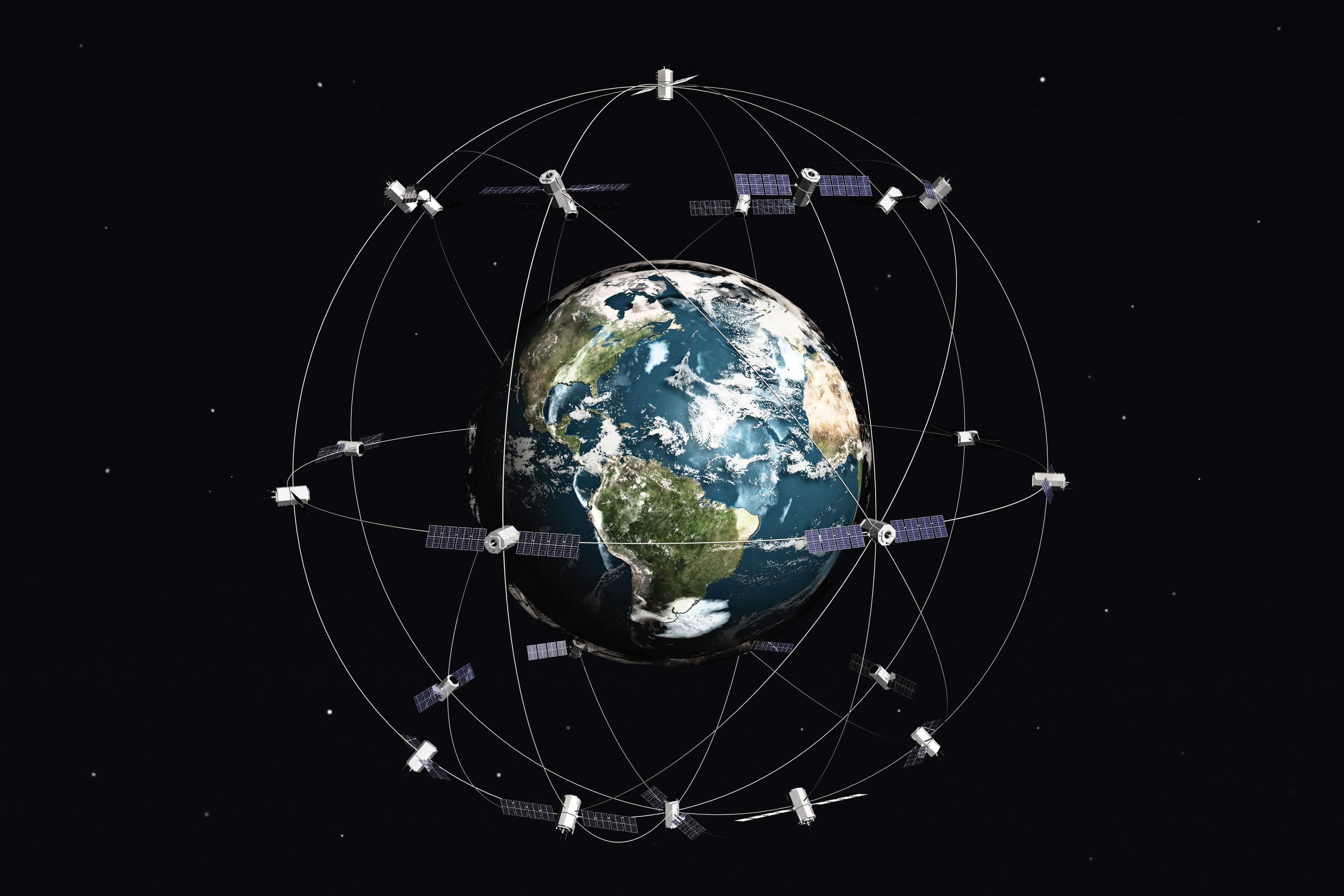

Remotely sensed satellite imagery is becoming increasingly common as satellites equipped with technologically advanced sensors are continually being sent into space by public agencies and private companies around the globe. Satellites are used for applications such as military and civilian earth observation, communication, navigation, weather, research, and more. Currently, more than 3,000 satellites have been sent to space, with over 2,500 of them originating from Russia and the United States. These satellites maintain different altitudes, inclinations, eccentricities, synchronies, and orbital centers, allowing them to image a wide variety of surface features and processes (Figure 4.14 "Satellites Orbiting the Earth").

Figure 4.14 Satellites Orbiting the Earth

Satellites can be active or passive. Active satellitesRemote sensors that detect reflected responses from objects that are irradiated from artificially generated energy sources. make use of remote sensors that detect reflected responses from objects that are irradiated from artificially generated energy sources. For example, active sensors such as radars emit radio waves, laser sensors emit light waves, and sonar sensors emit sound waves. In all cases, the sensor emits the signal and then calculates the time it takes for the returned signal to “bounce” back from some remote feature. Knowing the speed of the emitted signal, the time delay from the original emission to the return can be used to calculate the distance to the feature.

Passive satellitesRemote sensors that detect the reflected or emitted electromagnetic radiation from natural sources., alternatively, make use of sensors that detect the reflected or emitted electromagnetic radiation from natural sources. This natural source is typically the energy from the sun, but other sources can be imaged as well, such as magnetism and geothermal activity. Using an example we’ve all experienced, taking a picture with a flash-enabled camera would be active remote sensing, while using a camera without a flash (i.e., relying on ambient light to illuminate the scene) would be passive remote sensing.

The quality and quantity of satellite imagery is largely determined by their resolution. There are four types of resolution that characterize any particular remote sensor (Campbell 2002).Campbell, J. B. 2002. Introduction to Remote Sensing. New York: Guilford Press. The spatial resolutionThe smallest distance between two adjacent features that can be detected in an image. of a satellite image, as described previously in the raster data model section (Section 4.1 "Raster Data Models"), is a direct representation of the ground coverage for each pixel shown in the image. If a satellite produces imagery with a 10 m resolution, the corresponding ground coverage for each of those pixels is 10 m by 10 m, or 100 square meters on the ground. Spatial resolution is determined by the sensors’ instantaneous field of view (IFOV). The IFOV is essentially the ground area through which the sensor is receiving the electromagnetic radiation signal and is determined by height and angle of the imaging platform.

Spectral resolutionThe ability of a sensor to resolve wavelength intervals, also called bands, within the electromagnetic spectrum. denotes the ability of the sensor to resolve wavelength intervals, also called bands, within the electromagnetic spectrum. The spectral resolution is determined by the interval size of the wavelengths and the number of intervals being scanned. Multispectral and hyperspectral sensors are those sensors that can resolve a multitude of wavelengths intervals within the spectrum. For example, the IKONOS satellite resolves images for bands at the blue (445–516 nm), green (506–95 nm), red (632–98 nm), and near-infrared (757–853 nm) wavelength intervals on its 4-meter multispectral sensor.

Temporal resolutionThe amount of time between each image collection period determined by the repeat cycle of a satellite’s orbit. is the amount of time between each image collection period and is determined by the repeat cycle of the satellite’s orbit. Temporal resolution can be thought of as true-nadir or off-nadir. Areas considered true-nadir are those located directly beneath the sensor while off-nadir areas are those that are imaged obliquely. In the case of the IKONOS satellite, the temporal resolution is 3 to 5 days for off-nadir imaging and 144 days for true-nadir imaging.

The fourth and final type of resolution, radiometric resolutionThe sensitivity of a remote sensor to variations in brightness., refers to the sensitivity of the sensor to variations in brightness and specifically denotes the number of grayscale levels that can be imaged by the sensor. Typically, the available radiometric values for a sensor are 8-bit (yielding values that range from 0–255 as 256 unique values or as 28 values); 11-bit (0–2,047); 12-bit (0–4,095); or 16-bit (0–63,535) (see Chapter 5 "Geospatial Data Management", Section 5.1.1 "Data Types" for more on bits). Landsat-7, for example, maintains 8-bit resolution for its bands and can therefore record values for each pixel that range from 0 to 255.

Because of the technical constraints associated with satellite remote sensing systems, there is a trade-off between these different types of resolution. Improving one type of resolution often necessitates a reduction in one of the other types of resolution. For example, an increase in spatial resolution is typically associated with a decrease in spectral resolution, and vice versa. Similarly, geostationary satellitesSatellites that circle the earth proximal to the equator once each day. (those that circle the earth proximal to the equator once each day) yield high temporal resolution but low spatial resolution, while sun-synchronous satellitesSatellites that synchronize a near-polar orbit with the sun’s illumination. (those that synchronize a near-polar orbit of the sensor with the sun’s illumination) yield low temporal resolution while providing high spatial resolution. Although technological advances can generally improve the various resolutions of an image, care must always be taken to ensure that the imagery you have chosen is adequate to the represent or model the geospatial features that are most important to your study.

Aerial Photography

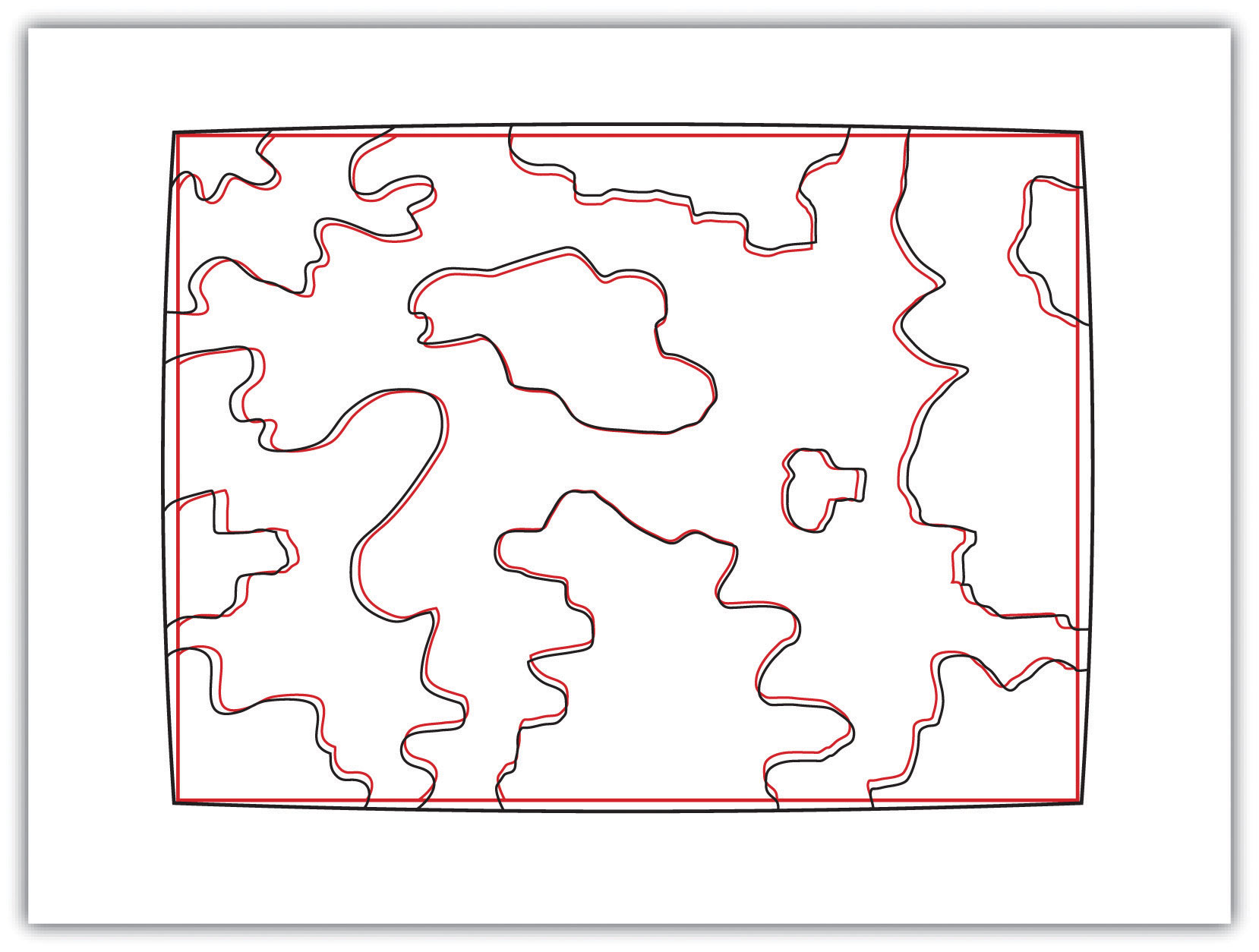

Aerial photography, like satellite imagery, represents a vast source of information for use in any GIS. Platforms for the hardware used to take aerial photographs include airplanes, helicopters, balloons, rockets, and so forth. While aerial photography connotes images taken of the visible spectrum, sensors to measure bands within the nonvisible spectrum (e.g., ultraviolet, infrared, near-infrared) can also be fixed to aerial sources. Similarly, aerial photography can be active or passive and can be taken from vertical or oblique angles. Care must be taken with aerial photographs as the sensors used to take the images are similar to cameras in their use of lenses. These lenses add a curvature to the images, which becomes more pronounced as one moves away from the center of the photo (Figure 4.15 "Curvature Error Due to Lenticular Properties of Camera").

Figure 4.15 Curvature Error Due to Lenticular Properties of Camera

Another source of potential error in an aerial photograph is relief displacement. This error arises from the three-dimensional aspect of terrain features and is seen as apparent leaning away of vertical objects from the center point of an aerial photograph. To imagine this type of error, consider that a smokestack would look like a doughnut if the viewing camera was directly above the feature. However, if this same smokestack was observed near the edge of the camera’s view, one could observe the sides of the smokestack. This error is frequently seen with trees and multistory buildings and worsens with increasingly taller features.

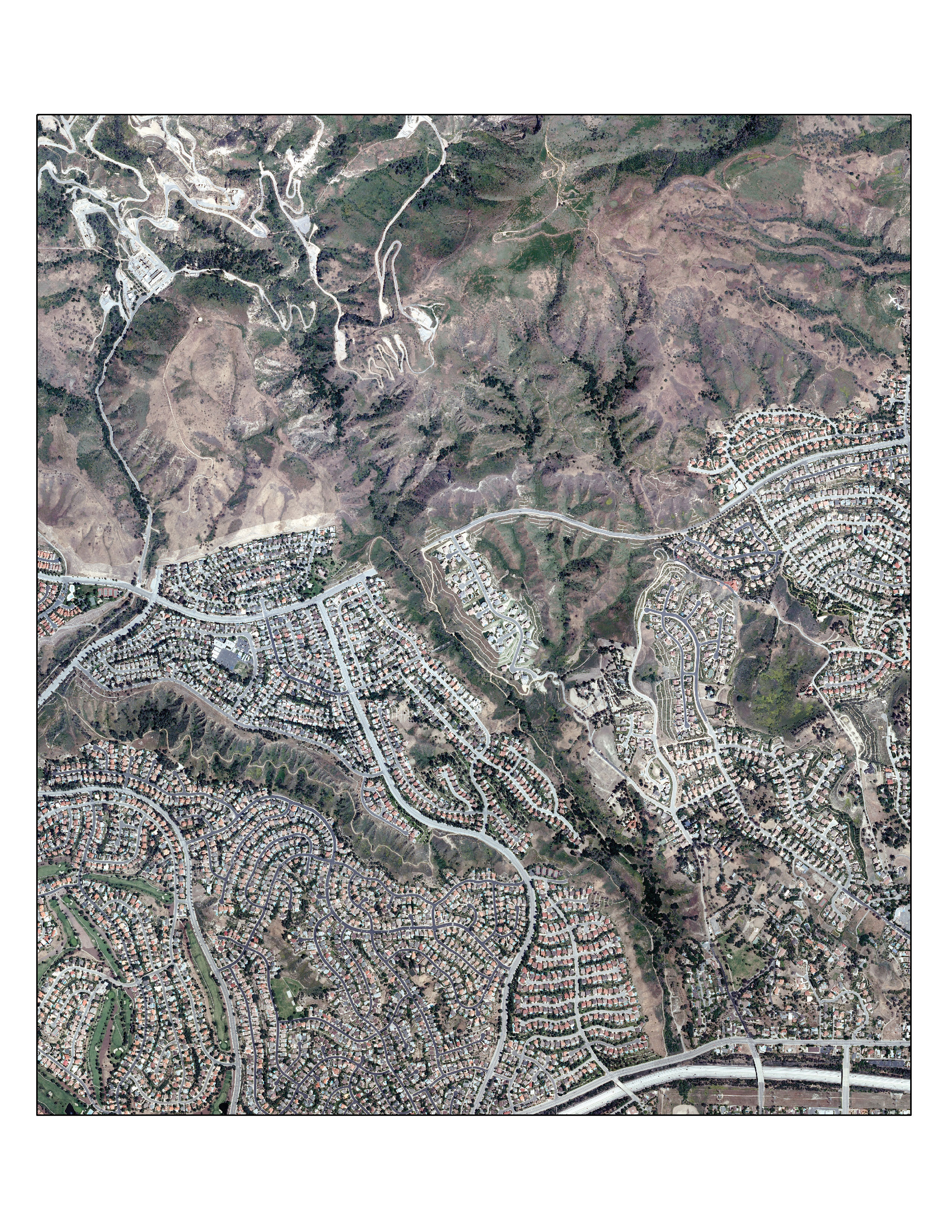

OrthophotosVertical photographs that have been geometrically “corrected” to remove the curvature and terrain-induced error from images. are vertical photographs that have been geometrically “corrected” to remove the curvature and terrain-induced error from images (Figure 4.16 "Orthophoto"). The most common orthophoto product is the digital ortho quarter quadrangle (DOQQ). DOQQs are available through the US Geological Survey (USGS), who began producing these images from their library of 1:40,000-scale National Aerial Photography Program photos. These images can be obtained in either grayscale or color with 1-meter spatial resolution and 8-bit radiometric resolution. As the name suggests, these images cover a quarter of a USGS 7.5 minute quadrangle, which equals an approximately 25 square mile area. Included with these photos is an additional 50 to 300-meter edge around the photo that allows users to mosaic many DOQQs into a single, continuous image. These DOQQs are ideal for use in a GIS as background display information, for data editing, and for heads-up digitizing.

Figure 4.16 Orthophoto

Source: Data available from U.S. Geological Survey, Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, SD.

Key Takeaways

- Satellite imagery is a common tool for GIS mapping applications as this data becomes increasingly available due to ongoing technological advances.

- Satellite imagery can be passive or active.

- The four types of resolution associated with satellite imagery are spatial, spectral, temporal, and radiometric.

- Vertical and oblique aerial photographs provide valuable baseline information for GIS applications.

Exercise

- Go to the EarthExplorer website (http://edcsns17.cr.usgs.gov/EarthExplorer) and download two satellite images of the area in which you reside. What are the different spatial, spectral, temporal, and radiometric resolutions for these two images? Do these satellites provide active or passive imagery (or both)? Are they geostationary or sun-synchronous?