This is “Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management”, chapter 21 from the book Enterprise and Individual Risk Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 21 Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management

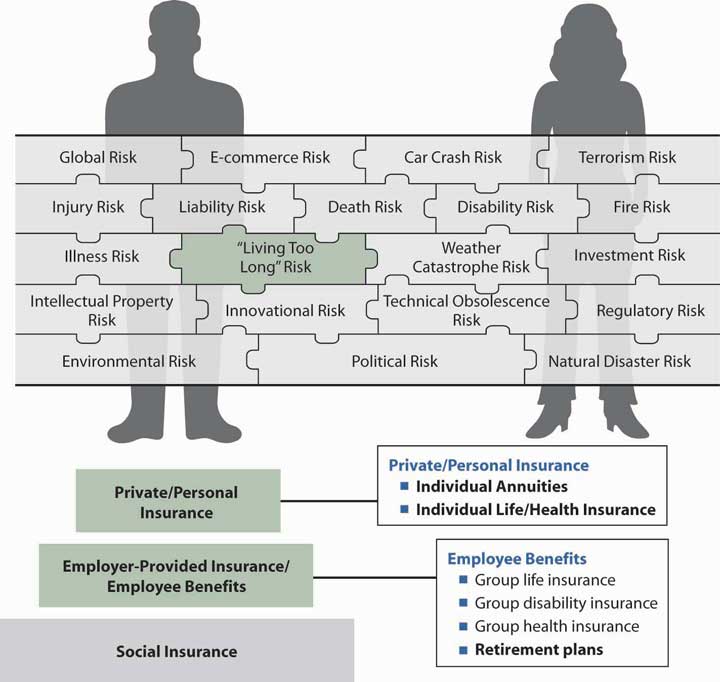

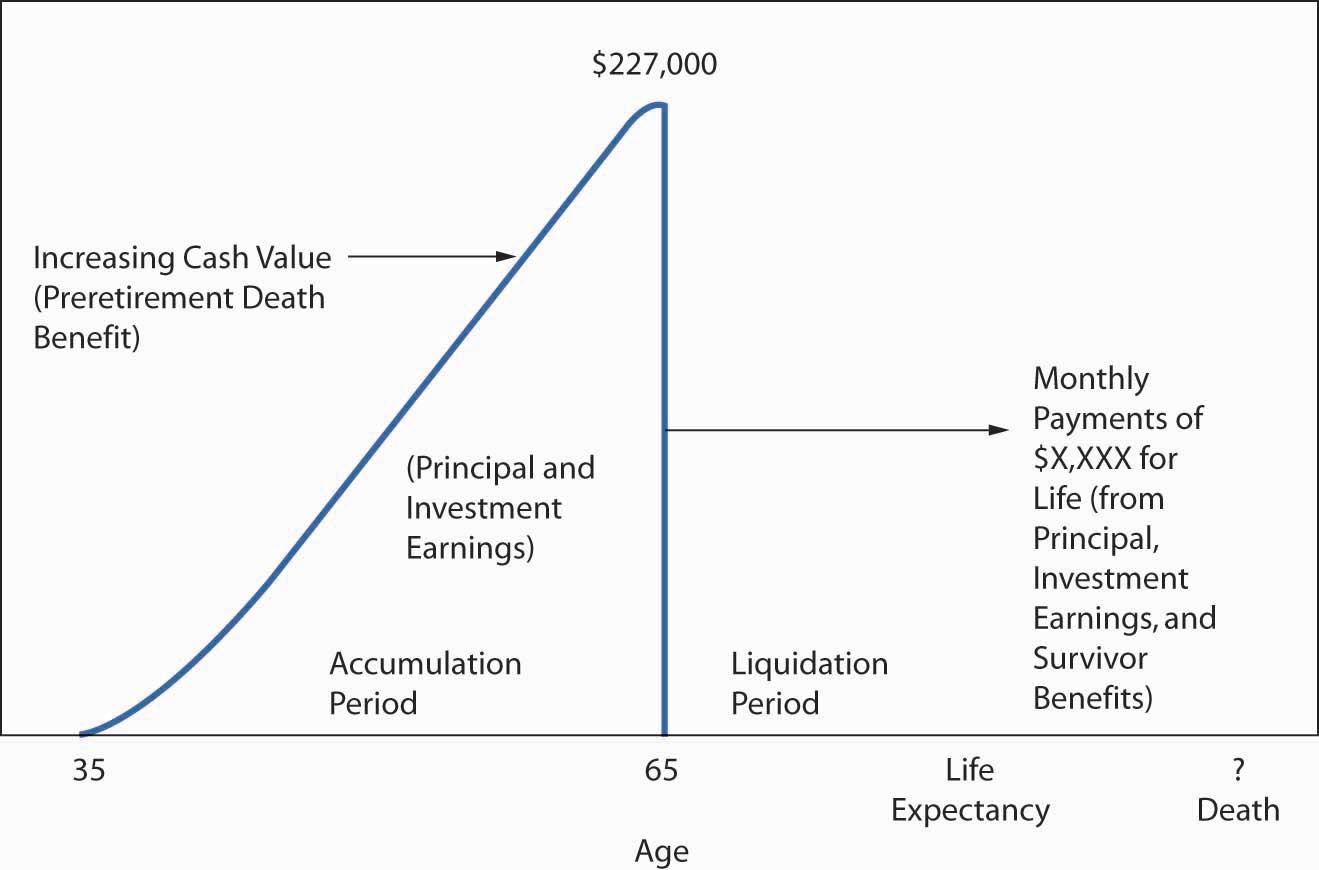

As noted earlier in this text, individuals rely on several sources for income during retirement: Social Security, employer-sponsored retirement plans, and individual savings (depicted in our familiar three-step diagram). In Chapter 18 "Social Security", we discussed how Social Security, a public retirement program, provides a foundation of economic security for retired workers and their families. Social Security provides only a basic floor of income; it was never intended to be the sole source of retirement income.

Employees may receive additional retirement income from employer-sponsored retirement plans. According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI), of the $1.5 trillion in total employee benefit program outlays in 2007, employers spent $693.9 billion on retirement plans. Retirement obligations, mostly in the form of mandatory social insurance programs, made up the largest portion of employer spending on benefits in 2007.Employee Benefits Research Institute, EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits, ch. 2: “Finances of the Employee Benefit System,” updated September 2008, http://www.ebri.org (accessed April 17, 2009). Private retirement benefits are an important component of employee compensation, especially because many large employers are transitioning from providing a promise at retirement through a defined benefits plan (as explained later) into helping employees invest in 401(k) plans. Big corporations such as IBM froze their promise for defined benefits plans for new employees entering employment with the company. Watson Wyatt Worldwide found that seventy-one Fortune 1,000 companies that sponsored defined benefits plans froze or terminated their defined benefits plans in 2004, compared with forty-five in 2003 and thirty-nine in 2002. An example is Hewlett Packard where, effective 2006, newly hired employees and those not meeting certain age and service criteria are covered by 401(k) with matching only.Judy Greenwald, “Desire for Certainty, Savings Drives Shift from DB Plans,” Business Insurance, September 19, 2005, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/article.pl?articleId=17551&a=a&bt=desire+for+certainty,+savings (accessed April 17, 2009); Jerry Geisel, “HP to Phase out Defined Benefit Plan,” Business Insurance, July 25, 2005, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/article.pl?articleId=17263&a=a&bt=hp+to+phase+out (accessed April 17, 2009); Jerry Geisel, “Congress Responds to Pension Failure Stories,” Business Insurance, July 11, 2005, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/article.pl?articleId=17156&a=a&bt=pension+failure+stories (accessed April 17, 2009).

These issues and more will be clarified in this chapter as we discuss the objectives of group retirement plans, how plans are structured and funded, and the current retirement crisis for the baby boomers (U.S. workers born between 1946 and 1964) who are entering their golden retirement years.Matt Brady, “ACLI: Bush Is Right About the Boomers,” National Underwriter Online News Service, February 1, 2006, http://www.lifeandhealthinsurancenews.com/News/2006/2/Pages/ACLI--Bush-Is-Right-About-The-Boomers.aspx?k=bush+is+right+about+the+boomers (accessed April 17, 2009). The chapter covers the following topics:

- Links

- The nature of qualified pension plans

- Types of qualified plans, defined benefits plans, defined contribution plans, other qualified plans, and individual retirement accounts (IRAs)

- Annuities

- Pension plan funding techniques

Links

In our search to complete the risk management puzzle of Figure 21.1 "Links between Holistic Risk Puzzle Pieces and Employee Benefits—Retirement Plans", we now add an important layer that is represented by the second step of the three-step diagram: employer-sponsored pension plans. The pension plans provided by the employer (in the second step of the three-step diagram) can be either defined benefit or defined contribution. Defined benefit pension plans ensure employees of a certain amount at retirement, leaving all risk to the employer who has to meet the specified commitment. Defined contribution, on the other hand, is a promise only to contribute an amount to the employee’s separate, or individual, account. The employee has the investment risk and no assurances of the level of retirement amount. Defined benefit plans are insured by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), a federal agency that ensures the benefits up to a limit in case the pension plan cannot meet its obligations. The maximum monthly amount of benefits guaranteed under the PBGC in 2009 for a straight life annuity at 65 percent is $4,500 and for joint and 50 percent survivor annuity (explained later) is $4,050.Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) News Division, “PBGC Announces Maximum Insurance Benefit for 2009,” November 3, 2008, http://www.pbgc.gov/media/news-archive/news-releases/2008/pr09-03.html (accessed April 17, 2009). The employee never contributes to this plan. The prevalence of this plan is on the decline in the new millennium. The PBGC protects 44 million workers and retirees in about 30,000 private-sector defined benefit pension plans.

Another trend that became prevalent and has received congressional attention is the move from the traditional defined benefit plans to cash balance plans, a transition that has slowed down in the first decade of the 2000s due to legal implications. Cash balance plans are defined benefit plans, though they are in a way a hybrid between defined benefit and defined contribution plans. More on cash balance plans, and all other plans, will be explained in this chapter and in the box “Cash Balance Conversions: Who Gets Hurt?”

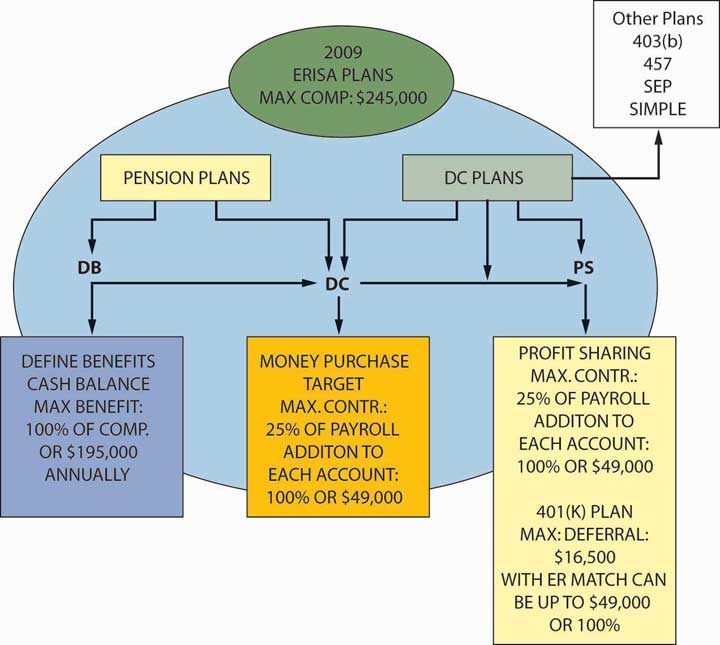

The most common plans are the defined contribution pension plans. As noted above, under this type of plan, the employer provides employees with the money and the employees invest the funds. If the employees do well with their investments, they may be able to enjoy a prosperous retirement. Under defined contribution plans, in most cases, employees have some choices for investments. Plans such as money purchase, profit sharing, and target plans are funded by employers. In another type of defined contribution plan, employees contribute toward their retirement by forgoing their income or deferring it on a pretax basis, such as into 401(k), 403(b), or 457 plans. There are also Roth 401(k) and 403(b) plans, where employees contribute to the plans on an after-tax basis and never pay taxes on the earnings. These plans are sponsored by employers, and an employer may match some portion of an employee’s contribution in some of these deferred compensation plans. Because it is the employees’ savings, they can say that it belongs in the third step of Figure 21.1 "Links between Holistic Risk Puzzle Pieces and Employee Benefits—Retirement Plans". However, because it is done through the employer, it is also part of the second step. The pension plans discussed in this chapter are featured in Figure 21.2 "Retirement Plans by Type, Limits as of 2009".

Figure 21.1 Links between Holistic Risk Puzzle Pieces and Employee Benefits—Retirement Plans

Figure 21.2 Retirement Plans by Type, Limits as of 2009

As you can see, we need to know what we are doing when we invest our defined contribution retirement funds. During the stock market boom of the late 1990s, many small investors put most of their retirement funds in stocks. By the summer of 2002, the stock market saw some of the worst declines in its history, with a rebound by 2006. Among the reasons for the decline were the downturn in the economy; the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001; and investors’ loss of trust in the integrity of the accounting numbers of many corporations. The fraudulent behavior of executives in companies such as Enron, WorldCom, and others led investors to consider their funds not just lost but stolen.Kara Scannell, “Public Pensions Come Up Short as Stocks’ Swoon Drains Funds,” Wall Street Journal, August 16, 2002. On July 29, 2002, President George W. Bush signed a bill for corporate governance or corporate responsibility to rebuild the trust in corporate America and punish fraudulent executives.Elisabeth Bumiller, “Bush Signs Bill Aimed at Fraud in Corporations,” New York Times, July 30, 2002. “The legislation, among other things, brought the accounting industry under federal supervision and stiffened penalties for corporate executives who misrepresent company finances.”Greg Hitt, “Bush Signs Sweeping Legislation Aimed at Curbing Business Fraud,” Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2002. Congress also worked on legislation to safeguard employee 401(k)s in an effort to prevent future disasters like the one suffered by Enron employees, who were not allowed (under the blackout period) to diversify their 401(k) investments and lost the funds when Enron declared bankruptcy. In May 2005, lawyers filed suits on behalf of AIG 401(k) participants, alleging that AIG violated the Employee Retirement Income Security Act by failing to disclose improper business practices and by disseminating false and misleading financial statements to investors that led to reductions in AIG stock prices.Jerry Geisel, “Senate Finance Committee Passes 401(k) Safeguards,” Business Insurance, July 11, 2002; “401(k) Participants File Class-Action Suit Against AIG,” BestWire, May 13, 2005; “Lawyers File Suit on Behalf of AIG Plan Members,” National Underwriter Online News Service, May 13, 2005. The reform objective is intended to give more oversight and safety measures to defined contribution plans because these plans do not enjoy the oversight and protection of the PBGC. The 2007–2008 economic recession has brought about a plethora of new problems and questions regarding the merits of defined contribution plans, which will be the subject of the box, “Retirement Savings and the Recession.”

In this chapter, we drill down into the specific pieces of the puzzle that bring us into many challenging areas. But we do need to complete the holistic risk management process we have started. This chapter delivers only a brief insight into the very broad and challenging area of pensions. Pensions are also featured as part of Case 2 in Chapter 23 "Cases in Holistic Risk Management".

21.1 The Nature of Qualified Pension Plans

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on distinguishing aspects of qualified retirement plans:

- Legislation affecting qualified retirement plans and their key provisions

- Eligibility criteria for qualified plans

- Determination of retirement age

- What is meant by vesting

- Nondiscrimination tests for qualified plans

- Treatment of plan distributions

- Loan provisions

A retirement plan may be qualified or nonqualified. The distinction is important to both employer and employee because qualification produces a plan with a favorable tax status. In a qualified planType of retirement plan where employer contributions to an employee’s pension during the employee’s working years are deductible as a business expense, are not taxable income to the employee until they are received as benefits, and investment earnings on funds held by the trustee for the plan are not subject to income taxes as they are earned., employer contributions to an employee’s pension during the employee’s working years are deductible as a business expense but are not taxable income to the employee until they are received as benefits. Investment earnings on funds held by the trustee for the plan are not subject to income taxes as they are earned.

Most nonqualifiedType of retirement plan that does not allow employer funding contributions to be deducted as business expenses unless classified as compensation to the employee (in which case they become taxable income for the employee), investment fund earnings are also subject to taxation, and retirement benefits are deductible business expenses when paid to the employee (if not previously classified as compensation). plans do not allow employer funding contributions to be deducted as a business expense unless they are classified as compensation to the employee, in which case they become taxable income for the employee. Investment earnings on these nonqualified accumulated pension funds are also subject to taxation. Retirement benefits from a nonqualified plan are a deductible business expense when they are paid to the employee, if not previously classified as compensation. Most nonqualified plans are for executives and designed to benefit only a small number of highly paid executives.

ERISA Requirements for Qualified Pension Plans

To be qualified, a plan must fulfill various requirements. These requirements prevent those in control of the organization from using the plan primarily for their own benefit. The following requirements are enforced by the United States Internal Revenue Service, the United States Department of Labor, and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC).

- The plan must be legally binding, in writing, and communicated clearly to all employees.

- The plan must be for the exclusive benefit of the employees or their beneficiaries.

- The principal or income of the pension plan cannot be diverted to any other purpose, unless the assets exceed those required to cover accrued pension benefits.

- The plan must benefit a broad class of employees and not discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees.

- The plan must be designed to be permanent and have continuing contributions.

- The plan must comply with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act and subsequent federal laws.

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974Federal law that regulates the design, funding, and communication aspects of qualified retirement plans; specifically, protects the benefits of plan participants and prevents discrimination in favor of highly compensated employees (those who control the organization). and subsequent amendments and laws—in particular, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86)—are federal laws that regulate the design, funding, and communication aspects of private, qualified retirement plans. The most recent amendments include the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA) of 2001Federal law that regulates the design, funding, and communication aspects of qualified retirement plans; allows increases in retirement savings limits and mandates faster participant vesting in employers’ matching contributions to defined contribution plans. and the Pension Protection Act of 2006Federal law that regulates the design, funding, and communication aspects of qualified retirement plans; specifically, added permanency to EGTRRA 2001 laws and provides greater portability, increases in flexibility in plan funding and design, and administrative simplification.. In practice, the term ERISA is used to refer to the 1974 act and all subsequent amendments and related laws. The purpose of ERISA is twofold: to protect the benefits of plan participants and to prevent discrimination in favor of highly compensated employees (that is, those who control the organization).ERISA defines highly compensated and nonhighly compensated employees based on factors such as employee salary, ownership share of the firm, and whether the employee is an officer in the organization.

Within the guidelines and standards established by ERISA and subsequent federal laws, the employer must make some choices regarding the design of a qualified retirement plan. The main items covered by ERISA and subsequent laws and amendments are the following:

- Employee rights

- Reporting and disclosure rules

- Participation coverage

- Vesting

- Funding

- Fiduciary responsibilities

- Amounts contributed or withdrawn

- Nondiscrimination

- Tax penalties

ERISA and all subsequent laws provide significant protection to plan participants. Over time, however, the nature of the work force changed from stable and permanent positions to mobile and transient positions, and it appeared that ERISA failed to address portability issues when employees changed jobs. ERISA and subsequent laws are also considered to have administrative difficulties and to be a burden on employers. While the percentage of the working population covered is still unchanged since 1974, the number of defined benefit plans has dropped significantly, from a high of 175,000 plans in 1983, and more employees are now covered under defined contribution plans. ERISA has a safety valve for defined benefit plans with the insurance provided by the PBGC. Plans such as 401(k)s do not have such a safety valve. Information on how to protect your pensions is available from the Department of Labor and is featured in the box “Ten Warning Signs That Pension Contributions Are Being Misused” in Chapter 20 "Employment-Based Risk Management (General)".

In 2001, EGTRRA addressed some of ERISA’s shortfalls and the 2006 Pension Protection Act provided some permanency to some of the EGTRRA laws. The new laws offer employers that sponsor plans more flexibility in plan funding and incentives by allowing greater tax deductions. The major benefits of EGTRRA are the increases in retirement savings limits and mandates of faster participant vesting in employers’ matching contributions to 401(k) plans. These changes became permanent with the adoption of the Pension Protection Act of 2006. Also, all employers’ contributions are now subject to faster vesting requirements. The new laws provide greater portability, increased flexibility in plan funding and design, and administrative simplification. The EGTRRA ten-year sunset provision was eliminated with the 2006 act.See information about the Pension Protection Act of 2006 at http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/pensionreform.html. For information about the pension laws, see many sources from the media, among them Vineeta Anand, “Lawyer Steven J. Sacher Says That for the Most Part ERISA Has Performed ‘Smashingly Well,’” Pensions & Investments, September 6, 1999, 19; Barry B. Burr, “Reviewing Options: Enron Fallout Sparks Much Soul-Searching; Experts Debate Need for Change Following Huge Losses in 401(k),” Pensions & Investments, 30 (2002): 1; William G. Gale et. al, “ERISA After 25 Years: A Framework for Evaluating Pension Reform,” Benefits Quarterly, October 1, 1998; Lynn Miller, “The Ongoing Growth of Defined Contribution and Individual Account Plans: Issues and Implications,” EBRI Issue Brief, no. 243 (2002), http://www.ebri.org/publications/ib/index.cfm?fa=ibDisp&content_id=160, accessed April 17, 2009; Martha Priddy Patterson, “A New Millennium for Retirement Plans: The 2001 Tax Act and Employer Flexibility,” Benefits Quarterly, January 1, 2002.

Eligibility and Coverage Requirements

A pension plan must establish eligibility criteriaDetermines who participates in employer pension plans, subject to ERISA, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, and other federal requirements. for determining who is covered. Most plans exclude certain classes of employees. For example, part-time or seasonal employees may not be covered. Separate plans may be set up for those paid on an hourly basis. Excluding certain classes of employees is allowed, provided the plan does not discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees, meets minimum eligibility requirements, and passes the tests noted below.

Under ERISA, the minimum eligibility requirements are the attainment of age twenty-one and one year of service. A year of service is defined as working at least 1,000 hours within a calendar year.The service requirement may be extended to two years in the small minority of plans that have immediate vesting. Vesting is defined later in the chapter. This is partly to reduce costs of enrolling employees who cease employment shortly after being hired, and partly because most younger employees attach a low value to benefits they will receive many years in the future. The Age Discrimination in Employment Act eliminates all maximum age limits for eligibility. Even when an employee is hired at an advanced age, such as seventy-one, the employee must be eligible for the pension plan within the first year of service if the plan is offered to other, younger hires in the same job.

In addition to eligibility rules, ERISA has coverage requirementsERISA provisions designed to improve participation in qualified pension plans by nonhighly compensated employees. that are designed to improve participation by nonhighly compensated employees. All employees of businesses with related ownership (called a controlled groupEmployees of businesses with related ownership; treated for coverage requirements as if employees of one plan.) are treated for coverage requirements as if they were employees of one plan.

Retirement Age Limits

To make a reasonable estimate of the cost of some retirement plans, mainly defined benefit plans, it is necessary to establish a retirement age for plan participants. For other types of plans, mainly defined contribution plans, setting a retirement age clarifies the age at which no additional employer contributions will be made to the employee’s plan. The normal retirement ageThe age at which full retirement benefits become available to retirees; age sixty-five in most private retirement plans. is the age at which full retirement benefits become available to retirees. Most private retirement plans specify age sixty-five as the normal retirement age.

Early retirement may be allowed, but that option must be specified in the pension plan description. Usually, early retirement permanently reduces the benefit amount. For example, an early retirement provision may allow the participant to retire as early as age fifty-five if he or she also has at least thirty years of service with the employer. The pension benefit amount, however, would be reduced to take into account the shorter time available for fund accumulation and the likely longer period that benefits will be paid out.

Early retirement plans used to be very appealing both to long-timers and to employers who saw replenishment of the work force. In 2001, companies such as Procter & Gamble, Tribune Company, and Lucent Technologies used early retirement as an alternative to layoffs. Since the decline of old-fashioned defined benefit pensions, employees have less incentive to take early retirement. With defined contribution plans, employees continue to receive the employer’s contribution or defer their compensation to a 401(k) plan as long as they work. The benefits are not frozen at a certain point, as in the traditional defined benefit plans. Mandatory retirement is considered age discrimination, except for executives in high policy-making positions. Thus, a plan must allow for late retirement. Deferral of retirement beyond the normal retirement age does not interfere with the accumulation of benefits. That is, working beyond normal retirement age may produce a pension benefit greater than would have been received at normal retirement age. However, a plan can set some limits on total benefits (e.g., $50,000 per year) or on total years of plan participation (e.g., thirty-five years). These limits help control employer costs.

Vesting Provisions

A pension plan may be contributory or noncontributory. A contributory planPension plan that requires the employee to pay all or part of pension fund contributions. requires the employee to pay all or part of the pension fund contribution. A noncontributory planPension plan funded only by employer contributions. is funded only by employer contributions; that is, the employee does not contribute at all to the plan. ERISA requires that if an employee contributes to a pension plan, the employee must be able to recover all these contributions, with or without interest, if she or he leaves the firm.

Employer contributions and earnings are available to employees who leave their employment only if the employees are vested. VestingIn pension plans, specifies the extent of employee’s right to benefits for which the employer has made contributions, subject to ERISA, EGTRRA 2001, TRA86, and other federal requirements., or the employee’s right to benefits for which the employer has made contributions, depends on the plan provisions. The TRA86 amendment to the original ERISA vesting schedule and EGTRRA 2001 established minimum standards to ensure full vesting within a reasonable period of time. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 provides that the minimum vesting requirements for employers’ contributions matches those that were required for 401(k)s by EGTRRA. For defined contribution plans, the employer can choose one of the two minimum vesting schedules (or better) as follows:

- Cliff vesting: full vesting of employer contributions after three years, as was the case for top-heavy plans and the employer-matching portion of 401(k) plans.

- Graded vesting: 20 percent vesting of employer contributions after two years, 40 percent after three years, 60 percent after four years, 80 percent after five years, and 100 percent after six years, as was the case in top-heavy plans and the employer-matching portion of 401(k) plans.

For defined benefit plans, the employer can choose one of the two minimum vesting schedules (or better) as follows:

- Cliff vesting: full vesting of employer contributions after five years, as was the case for top-heavy plans and the employer-matching portion of 401(k) plans.

- Graded vesting: 20 percent vesting of employer contributions after three years, 40 percent after four years, 60 percent after five years, 80 percent after six years, and 100 percent after seven years.

Top-heavy plansPension plans in which the owners or highest-paid employees hold over 60 percent of the value of the plans. are those in which the owners or highest-paid employees hold over 60 percent of the value of the pension plan. The dollar limitation under Section 416(i)(1)(A)(i) concerning the definition of key employee in a top-heavy plan has increased from $150,000 in 2008, to $160,000 in 2009.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html, accessed April 17, 2009. If an employer has a top-heavy defined benefit plan, the minimum vesting schedule is as of the defined contribution plans.

Nondiscrimination Tests

The employer’s plan must meet one of the following coverage requirements:

- Percentage ratio test: The percentage of covered nonhighly compensated employees must be at least 70 percent of highly compensated employees who are covered under the pension plan. For example, if only 90 percent of the highly compensated employees are in the pension plan, only 63 percent (70 percent times 90 percent) of nonhighly compensated employees must be included.

- Average benefit test: The average benefit (expressed as a percentage of pay) for nonhighly compensated employees must be at least 70 percent of the average benefit for the highly compensated group.

The limitation used in the definition of highly compensated employee under Section 414(q)(1)(B) has increased from $105,000 in 2008 to $110,000 in 2009.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html, accessed April 17, 2009. Although the objective of coverage rules is to improve participation by nonhighly compensated employees, the expense and administrative burden of compliance discourages small employers from having a qualified retirement plan.

Distributions

Distributions are benefits paid out to participants or their beneficiaries, usually at retirement. Tax penalties are imposed on plan participants who receive distributions (except for disability benefits) prior to age fifty-nine and a half. However, the law requires that benefits begin by age seventy and a half, whether retirement occurs or not. Depending on the provisions of the particular plan, distributions may be made (1) as a lump sum, (2) as one of several life annuity options (as explained in the settlement options in Chapter 19 "Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance"), or (3) over the participant’s life expectancy. At age seventy and a half, the distribution requirements under ERISA direct the retiree to collect a minimum amount each year based on longevity tables.April K. Caudill, “More Clarity and Simplicity in New Required Minimum Distribution Rules,” National Underwriter, Life & Health/Financial Services Edition, May 13, 2002. Because of recent census data, Congress directed changes in the required minimum distribution calculations under EGTRRA 2001.The regulations state that the new method can be used to calculate substantially equal periodic payments under Section 72(t)—distributions of retirement funds after age seventy and a half.

The longest time period over which benefits may extend is the participant’s life expectancy. ERISA requires that pension plan design make spousal benefits available. Once the participant becomes vested, the spouse automatically becomes eligible for a qualified preretirement survivor annuityProvision made possible once a participant becomes vested in a pension plan that gives lifetime benefits to the spouse if the participant dies before the earliest retirement age allowed by the plan.. This provision gives lifetime benefits to the spouse if the participant dies before the earliest retirement age allowed by the plan. Once the participant reaches the earliest retirement age allowed by the plan, the spouse becomes eligible for benefits under a joint and survivor annuityProvision made possible once a participant reaches the earliest allowed retirement age that qualifies the spouse for a lifetime benefit in the event of the participant’s death (in most cases, 50 percent of the annuity). option. This qualifies the spouse for a lifetime benefit in the event of the participant’s death. In most cases, the spouse receives 50 percent of the annuity. Upon the employee’s retirement, the spouse remains eligible for this benefit. These benefits may be waived only if the spouse signs a notarized waiver.

Loans

Employees who need to use their account balances are advised to take a loan rather than terminate their employment and receive distribution. The distribution results not only in tax liability but also in a 10 percent penalty if the employee is younger than 59½ years old. The loan provisions require that an employee can take only up to 50 percent of the vested account balance for not more than $50,000. A loan of $10,000 may be made even if it is greater than 50 percent of the vested account balance. The number of loans is not limited as long as the total amount is within the required limits. Some employers do not provide loan provisions in their retirement plan.

Key Takeaways

In this section you studied qualified employee retirement plans, which allow tax-deductible contributions for employees and tax deferral for employees:

- Requirements are set forth by ERISA, EGTRRA 2001, TRA86, the Pension Protection Act, the IRS, and the PBGC for plans to meet qualified status.

- Eligibility criteria establish which employees are covered under a plan, and the eligibility criteria must comply with ERISA coverage requirements and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act regarding the rights of older workers.

- Normal retirement age is stipulated by employers; if allowed, early retirement reduces benefits; late retirement increases benefits.

- TRA86, ERISA, EGTRAA 2001, and the Pension Protection Act of 2006 establish minimum vesting standards regarding employees’ rights to employers’ contributions to retirement plans.

- Qualified plans must meet either the percentage ratio or average benefit nondiscrimination tests.

- The IRS imposes tax penalties on participants who receive distributions from retirement plans prior to age fifty-nine and a half and requires that benefits begin by age seventy and a half (regardless of retirement occurring).

- Spouses are entitled to preretirement survivor and joint and survivor annuity options once participants are vested or reach the earliest allowed retirement age.

- Some plans allow a participant to take loans in amounts of up to 50 percent of a vested account balance, for no more than $50,000, at a 10 percent tax penalty if the participant is under 59½ years old.

Discussion Questions

- What is the PBGC? Why is it an important agency?

- List ERISA requirements for qualified pension plans.

-

If an employer has 1,000 employees with 30 percent made up of highly compensated employees and 70 percent made up of nonhighly compensated employee, would the employers pass the ratio test

- if 200 nonhighly compensated employees are in the pension plan and all highly compensated employees are in the pension plan? Explain.

- if 200 nonhighly compensated employees are in the pension plan and only 50 percent of the highly compensated employees are in the pension plan? Explain.

- Why was the ratio test created for qualified pension plans?

- Explain briefly the changes brought about by the Pension Protection Act of 2006.

- What happens to an employee’s retirement benefits if he or she leaves a job after five years?

-

An employer is considering the following vesting schedules. Determine if these schedules comply with the laws governing qualified retirement plans:

- In a defined benefit plan, full vesting after six years.

- In a defined benefit plan, 60 percent vesting after six years and 100 percent vesting after seven years.

- In a defined contribution plan, 40 percent vesting after three years and 100 percent vesting at six years

- In a defined contribution plan, 100 percent vesting after two years.

- There has been a proposal that all private pension plans be required to provide full vesting at the end of one year of participation. If you were the owner of a firm employing fifty people and had a qualified pension plan, how would you react to this proposal? Explain your answer.

- Under what circumstances would an employee elect to take a loan out of his or her defined contribution plan, rather than ask for the money?

21.2 Types of Qualified Plans, Defined Benefit Plans, Defined Contribution Plans, Other Qualified Plans, and Individual Retirement Accounts

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on the various qualified plans available through employers or on an individual basis:

- Defined benefit pension plans: traditional defined benefit plan, cash balance plan

- Defined contribution retirement plans: cash balance plan, 401(k), profit sharing

- Special types of qualified plans: 403(b), Section 457, Keogh, SEP, SIMPLE

- Individual retirement accounts (IRAs): traditional IRA, Roth IRA, Roth 401(k), Roth 403(b)

Types of Qualified Plans

As noted above and as shown in Figure 21.2 "Retirement Plans by Type, Limits as of 2009", employers choose a pension plan from two types: defined benefit or defined contribution. Both are qualified plans that provide tax-favored arrangements for retirement savings.

Figure 21.2 "Retirement Plans by Type, Limits as of 2009" displays the different qualified retirement plans. Defined benefit (DB) and defined contribution (DC) pension plans are shown in the first two left-hand squares. The defined contribution profit-sharing (PS) plan is shown in the third left-hand rectangle. The leftmost square represents the highest level of financial commitment by an employer; the profit-sharing rectangle represents the least commitment. The profit-sharing plan is funded at the discretion of the employer during periods of profits, whereas pension plans require annual minimum funding. This is why the employer is giving greater commitment to pension plans—contributions are required even in bad years. Among the pension plans, the traditional defined benefit plan represents the highest level of employer’s commitment. It is a promise that the employee will receive a certain amount of income replacement at retirement. The benefits are defined by a mathematical formula, as will be shown later. Actuaries calculate the amount of the annual contribution necessary to fund the retirement promise given by the employer. As noted above, the PBGC provides insurance to guarantee these benefits (up to the maximum shown above) at a cost to the employer of $34 per employee per year (since 2009). Because the traditional defined benefit pension plan is the plan with the greatest commitment, usually a high level of contribution is allowed for older employees. The annual compensation limit under IRS sections 401(a)(17), 404(l), 408(k)(3)(C), and 408(k)(6)(D)(ii) has increased from $230,000 in 2008 to $245,000 in 2009, and the limitation on the annual benefit under a defined benefit plan under Section 415(b)(1)(A) has increased from $185,000 to $195,000 in 2009 or 100 percent of compensation.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009). These are shown in Figure 21.2 "Retirement Plans by Type, Limits as of 2009".

Another defined benefit plan is the cash balance plan. As discussed above, it is a hybrid of the traditional defined benefit plan and defined contribution plans. In a cash balance plan, the employer commits to contribute a certain percentage of compensation each year and guarantees a rate of return. Under this arrangement, employees are able to calculate the exact lump sum that will be available to them at retirement because the employer guarantees both contributions and earnings. This plan favors younger employees. It is currently the topic of court cases and debate because many large corporations such as IBM converted their traditional defined benefits plans to cash balance, grandfathering the older employees’ benefits under the plan.For more information, see coverage of this topic in the following sample of articles: “Sun Moves to Cash Balance Pensions,” Employee Benefit Plan Review 45, no. 9 (1991): 50–51; Arleen Jacobius, “Motorola Workers Embrace New Hybrid Pension Plan,” Business Insurance 34, no. 45 (2000): 36–37; Karl Frieden, “The Cash Balance Pension Plan: Wave of the Future or Shooting Star?” CFO: The Magazine for Chief Financial Officers 3, no. 9 (1987): 53–54; September 1987; Avra Wing, “Employers Wary of Cash Balance Pensions,” Business Insurance 20, no. 39 (1986): 15–20; September 29, 1986; Arleen Jacobius, “60 percent of Workers at Motorola, Inc. Embrace Firm’s New PEP Plan,” Pensions & Investment Age 28, no. 19 (2000): 3, 58; Jerry Geisel, “Survey Aims to Find Facts About Cash Balance Plans,” Business Insurance 34, no. 21 (2000): 10–12; “American Benefits Council President Discusses Cash Balance Plans, Pension Reform,” Employee Benefit Plan Review 55, no. 4 (2000): 11–13; Donna Ritter Mark, “Planning to Implement a Cash Balance Pension Plan? Examine the Issues First,” Compensation & Benefits Review 32, no. 5 (2000): 15–16; Vineeta Anand, “Young and Old Hurt in Switch to Cash Balance,” Pensions & Investment Age 28, no. 20 (2000): 1, 77; Vineeta Anand, “Employees Win Another One in Cash Balance Court Cases,” Pensions & Investment Age 28, no. 19 (2000): 2, 59; Regina Shanney-Saborsky, “The Cash Balance Controversy: Navigating the Issues,” Journal of Financial Planning 13, no. 9 (2000): 44–48. See the box, “Cash Balance Conversions: Who Gets Hurt?”

A cash balance plan is considered a hybrid plan because the contributions are guaranteed. The benefits are not explicitly defined but are the outcome of the length of time the employee is in the pension plan. Because both the contributions and rates of return are guaranteed, the amount available at retirement is therefore also guaranteed. It is an insured plan under the PBGC, and all funds are kept in one large account administered by the employer. The employees have only hypothetical accounts that are made of the contributions and the guaranteed returns. As noted above, it is a defined benefit plan that looks like a defined contribution plan.

The simplest of the defined contribution pension plans is the money purchase plan. Under this plan, the employer guarantees only the annual contribution but not any returns. As opposed to a defined benefit plan, where the employer keeps all the monies in one account, the defined contribution plan has separate accounts under the control of the employees. The investment vehicles in these accounts are limited to those selected by the employer who contracts with various financial institutions to administer the investments. If employees are successful in their investment strategy, their retirement benefits will be larger. The employees are not assured an amount at retirement, and they have the investment risk, not the employer. This aspect is illuminated by the 2008–2009 recession and discussed in the box “Retirement Savings and the Recession.” Because the employer is at less of an investment risk here and the employer’s commitment is lower, the tax benefit is not as great (especially for older employees). The limitation for defined contribution plans under Section 415(c)(1)(A) has increased from $46,000 in 2008 to $49,000 in 2009 or 100 percent of the employee’s compensation.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009).

Another defined contribution plan is the target pension plan, which favors older employees. This is another hybrid plan, but this is actually a defined contribution plan (subject to the $49,000 and 100 percent limitation in 2009) that looks like a traditional defined benefits plan in its first year only. Details about this plan are beyond the scope of this text.

For employers seeking the least amount of commitment, the profit-sharing plan is the solution. These are defined contribution plans that are not pension plans. There is no minimum funding requirements each year. As of 2003 and onward, the maximum allowed tax deductible contribution by employer per year is 25 percent of payroll. This is also a major change in effect after the enactment of EGTRRA 2001. The level used to be only 15 percent of payroll, with limits of an annual addition to each account of $35,000 or 25 percent in 2001. The additions to each account are up to the lesser of $49,000 or 100 percent of compensation in 2009.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009). The 401(k) is part of the tax code for a profit-sharing plan, but it is not designed as an employer contribution. Rather, it is a pretax-deferred compensation contribution by the employee with possible matching by an employer. See Tables 21.6 and 21.7 later in this chapter for the limits if the employer meets the discrimination testing or falls under certain safe-harbor provisions. As shown, EGTRRA 2001 increased the permitted deferred compensation under 401(k) plans gradually up to $16,500Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009). (in 2009) from the level of $10,500 in 2001. On January 1, 2006, Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §402A providing for Roth 401(k)s and Roth 403(b)s (discussed later) became effective. This also is an outcome of EGTRRA 2001 with a delayed effective date. Roth 401(k) and Roth 403(b) means that the contributions are after-tax, but earnings are never taxed. EGTRRA 2001 has catch-up provisions. The explanation of the 401(k) plan includes an example of the average deferral percentage (ADP) discrimination test used for 401(k) plans. When an employer adds matching, profit sharing, or any other defined contribution plans, the amount of annual additions to the individual accounts cannot exceed the lesser of $49,000 or 100 percent of compensation, including the 401(k) deferral in 2009.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009). The combination of 401(k) and any other profit-sharing contributions cannot exceed 25 percent of payroll. Nearly two-thirds of all U.S. large employers consider the 401(k) as the main retirement plan for their employees.“New Research from EBRI: Defined Contribution Retirement Plans Increasingly Seen as Primary Type,” Reuters, February 9, 2009, http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS166119+09-Feb-2009+PRN20090209, accessed March 10, 2009.

An employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) is another type of profit-sharing plan. An ESOP is covered only briefly in this text. This section also provides a brief description of other qualified plans such as 403(b), 457, Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE), Simplified Employee Pension (SEP), traditional IRA, and Roth IRA. EGTRRA 2001 made major changes to these plans, as well as to the plans discussed so far. Traditional IRA and Roth IRA are not sponsored by the employer, but require employee compensation through employment.

Cash Balance Conversions: Who Gets Hurt?

Over the past two decades, a number of employers have switched their traditional defined benefit pension plans to cash balance plans. Employers like cash balance plans because they are less expensive than traditional plans, in part, because they do not require the high administrative cost and large contributions for employees who are near retirement. Also, cash balance benefit plans may pay out less because they base their benefits on an employee’s career earnings, while defined benefit plans are based on the final years of salary, when earnings usually peak.

In November 2002, Delta Airlines joined the cash balance trend, citing the soaring costs of its underfunded traditional pension plan as the reason. Like Delta, many companies have implemented cash balance plans by converting their old defined benefit plans. In doing so, they determine an employee’s accrued benefit under the old plan and use it to set an opening balance for a cash balance account. While the opening account of a cash balance account can end up being less than the actual present value of the benefits an employee has already accrued (called wear away), cash balance plans have the advantage of portability. The traditional defined benefits plan is not portable because an employee who leaves a job may need to leave the accrued and vested benefits with the employer until retirement. Cash balance plans are considered very portable. The plan is similar to defined contribution plans because the employee knows at any moment the value of his or her hypothetical account that is built up as an accumulation of employer’s contributions and guaranteed rate of return. For this reason, cash balance plans are advertised as advantageous for today’s mobile work force. Also, cash balance plans are considered best for younger workers because these employees have many years to accumulate their hypothetical account balances.

However, these conversions have not been free of major controversies. Older employees, who do not have a long enough time to accumulate the account balance, in most cases are granted continuation under the old plan, under a grandfather clause. Midcareer employees in their forties have most to risk because it is uncertain whether the new cash balance plans can actually catch up to the old promise of defined benefits at age sixty-five. Plan critics have repeatedly charged that pay credits discriminate against older employees because the credits they receive would purchase a smaller annuity at normal retirement age than would those received by younger employees. Numerous lawsuits alleging discrimination have been filed against employers offering the plans.

IBM’s conversion in 1999 provides a notorious example of the pitfalls of conversion for midcareer employees. When IBM announced the conversion, it was inundated with hundreds of thousands of e-mails complaining about the change, so the company repeatedly tweaked its plan. Still, many employees are not satisfied when they compare the new plan with the defined benefit plan they might otherwise have received. A federal court gave a final approval to partial settlement between IBM and tens of thousands of current and former employees about the conversion. Under one part of the settlement, IBM has to pay more than $300 million to plan participants in the form of enhanced benefits. Since the partial settlement was proposed, IBM had frozen its cash balance plan, with employees hired as of January 1, 2005, receiving pension coverage under an enriched 401(k) plan.

The 2005 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report regarding cash balance pension plans concluded that cash balance plans do cut benefits. In July 2005, congressional committees passed legislation to make clear that cash balance plans do not violate age discrimination law, but the measures do not apply to existing plans. This relates to a court case that provided victory for employers. The judge dismissed a case against PNC Financial Services Group that was brought on behalf of its employees and retirees in connection with the company’s switch to a cash balance plan. The Pittsburgh-based PNC replaced its traditional defined benefit plan in 1999. The plaintiffs filed suit against the company and its pension plan in December 2004, arguing that the plan was age discriminatory, among other allegations. Judge D. Davis Legrome of the U.S. District Court in Philadelphia dismissed all the charges against the company in his decision (Sandra Register v. PNC Financial Services Group, Inc.).

To soften the effects of cash balance conversion, many companies offer transitional benefits to older employers. Some companies allow their workers to choose between the traditional plan and the cash balance plan. Others offer stock options or increased contributions to employee 401(k) plans to offset the reduction in pension benefits.

Questions for Discussion

- Who actually is the beneficiary of the conversions? The employer? All employees? Or only some? Is it ethical to change promises to employees?

- Are conversions to cash balance plans a reflection of the lowering of the noncash compensation (pension offering) of employers in the last two decades? Or are they just a smart move to accommodate the mobile work force? Is it ethical to make a noncash compensation reduction without reaching an agreement with employees?

- Is the fact that many employers are trying to get away from the traditional defined benefits plans that are similar to the current Social Security system a signal that Social Security will be privatized? Would it be ethical to make changes that may not be clear to employees (see Chapter 18 "Social Security")?

Sources: Jerry Geisel, “Delta’s New Pension Plan to Generate Big Savings,” Business Insurance, November 25, 2002, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/article.pl?articleId=12013&a=a&bt=delta’s+new+pension+plan (accessed April 17, 2009); Jonathan Barry Forman, “Legal Issues in Cash Balance Pension Plan Conversions,” Benefits Quarterly, January 1, 2001, 27–32; Lawrence J. Sher, “Survey of Cash Balance Conversions,” Benefits Quarterly, January 1, 2001, 19–26; Robert L. Clark, John J. Haley, and Sylvester J. Schieber, “Adopting Hybrid Pension Plans: Financial and Communication Issues,” Benefits Quarterly, January 1, 2001, p. 7–17; “Cash Balance Plans Questions & Answers,” U.S. Department of Labor, November 1999, https://www.dol.gov/ebsa/publications/cb_pension_plans.html (accessed April 17, 2009); Jerry Geisel, “Proposed Rules Clarify Cash Balance Plan Status,” Business Insurance, December 10, 2002.; Jerry Geisel “Court Gives Final Approval in IBM Pension Case,” Business Insurance, August 15, 2005, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/article.pl?articleId=17389&a=a&bt=court+gives+final+approval+ibm (accessed April 17, 2009); Jerry Geisel, “Effort to Dispel Cash Balance Doubts Criticized for Ignoring Existing Plans,” Business Insurance , August 1, 2005, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/article.pl?articleId=17312&a=a&bt=effort+to+dispel+cash+balance (accessed April 17, 2009); Judy Greenwald, “Court Ruling Favors Cash Balance Conversions,” Business Insurance, November 23, 2005, http://www.businessinsurance.com/cgi-bin/news.pl?newsId=6781, accessed April 17, 2009; Jerry Geisel “Cash Balance Plan Conversions Cut Benefits: GAO,” Business Insurance, November 4, 2005.

Defined Benefit Plans

A defined benefit (DB) planType of pension plan that assures employees of a certain amount at retirement, leaving all risk to the employer to meet the specified commitment; accumulated funds for all participants are managed in one account. has the distinguishing characteristic of clearly defining, by its benefit formula, the amount of benefit that will be available at retirement. That is, the benefit amount is specified in the written plan document, although the amount that must be contributed to fund the plan is not specified.

Traditional Defined Benefit Plan

In a defined benefit plan, any of several benefit formulas may be used in the following:

- A flat dollar amount

- A flat percentage of pay

- A flat amount unit benefit

- A percentage unit benefit

Each type has advantages and disadvantages, and the employer selects the formula that best meets both the needs of employees for economic security and the budget constraints of the employer.

The defined benefit formula may specify a flat dollar amount, such as $500 per month. It may provide a formula by which the amount can be calculated, yielding a flat percentage of current annual salary (or the average salary of the past five years or so). For example, a plan may specify that each employee with at least twenty years of participation in the plan receives 50 percent of his or her average annual earnings during the three consecutive years of employment with the highest earnings. A flat amount unit benefit formula assigns a flat amount (e.g., $25) with each unit of service, usually with each year. Thus, an employee with thirty units of service at retirement would receive a benefit equal to thirty times the unit amount.

The most popular defined benefit formula is the percentage unit benefit plan. It recognizes both the employee’s years of service and level of compensation. See Table 21.1 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Defined Benefit Pension Plan (Service Unit Formula, 2009)" for an example. Tables 21.1 through 21.5 feature different qualified retirement plans for the Slone-Jones Dental Office. The dental office is used as an example to demonstrate how each plan would work for the same mix of employees.

Table 21.1 The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Defined Benefit Pension Plan (Service Unit Formula, 2009)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | Current Age | Current Salary | Allowable Compensation | Years of Service | Years of Service to Age 65 | Maximum Allowed Benefit | Expected Benefit at Age 65 2% × (3) × (5) |

| Dr. Slone | 55 | $250,000 | $245,000 | 20 | 30 | $195,000 | $90,000 |

| Diane | 45 | $55,000 | $55,000 | 10 | 30 | 55,000 | $11,000 |

| Jack | 25 | $30,000 | $30,000 | 5 | 45 | 30,000 | $3,000 |

When the compensation base is described as compensation for a recent number of years (e.g., the last three or highest consecutive five years), the formula is referred to as a final average formulaSets the compensation base as compensation for a recent number of years (e.g., the last three or highest consecutive five years) in computing the retirement benefit in a defined benefit plan; tends to keep the initial benefit in line with inflation.. Relative to a career average formulaBases benefits on average compensation for all years of service under the plan in computing the retirement benefit in a defined benefit plan., which bases benefits on average compensation for all years of service in the plan, a final average plan tends to keep the initial retirement benefit in line with inflation.

Two types of service are involved in the benefit formula: past service and future service. Past service refers to service prior to the installation of the plan. Future service refers to service subsequent to the installation of the plan. If credit is given for past service, the plan starts with an initial past service liability at the date of installation. To reduce the size of this liability, the percentage of credit for past service may be less than that for future service, or a limit may be put on the number of years of past service credit. Initial past service liability may be a serious financial problem for the employer starting or installing a pension plan. Past service liability or supplemental liabilityIn a retirement benefit formula, past service liability giving credit to employees’ service prior to the adoption of a defined benefits plan; can be amortized over a certain number of years. can be amortized over a certain number of years, not to exceed thirty years for a single employer.

Cash Balance Plan

The cash balance planDefined benefit plan that is a hybrid of the traditional defined benefit plan and a defined contribution plan where the employer commits to contribute a certain percentage of compensation each year and guarantees a rate of return such that employees can calculate the exact lump sum that will be available at retirement (since the employer guarantees both contributions and earnings). does not provide an amount of benefit that will be available for the employee at retirement. Instead, the cash balance plan sets up a hypothetical individual account for each employee, and credits each participant annually with a plan contribution (usually a percentage of compensation). The employer also guarantees a minimum interest credit on the account balance. For example, an employer might contribute 10 percent of an employee’s salary to the employee’s plan each year and guarantee a minimum rate of return of 4 percent on the fund, as shown in Table 21.2 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Cash Balance Plan (2009)". If investment returns turn out to be higher than 4 percent, the employer may credit the employee account with the higher rate. The amount available to the employee at retirement varies, based on wage rates and investment rates of return. Although the cash balance plan is technically a defined benefit plan, it has many of the same characteristics as defined contribution plans. These characteristics include hypothetical individual employee accounts, a fixed employer contribution rate, and an indeterminate final benefit amount because employee compensation changes over time and interest rates may turn out to be well above the minimum guaranteed rate.

Table 21.2 The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Cash Balance Plan (2009)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | Current Age | Current Salary | Allowed Compensation | Maximum Benefit | Contribution Year (10%) | Years to Retirement | Future Value of $1 Annuity at 4% | Lump Sum at Age 65 (7) × (5) |

| Dr. Slone | 55 | $250,000 | $245,000 | $195,000 | $24,500 | 10 | 12.006 | $294,147 |

| Diane | 45 | $55,000 | $55,000 | 55,000 | $5,500 | 20 | 29.778 | $163,779 |

| Jack | 25 | $30,000 | $30,000 | 30,000 | $3,000 | 40 | 95.024 | $285,072 |

Features of Defined Benefit Plans

All defined benefit plans may provide for adjustments to account for inflation during the retirement years. A plan that includes a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA)Increases retirement benefits automatically with changes in a cost-of-living or wage index to account for inflation during retirement years. clause has the ideal design feature. Benefits increase automatically with changes in a cost-of-living or wage index.

Many plans integrate the retirement benefit with Social Security benefits. An integrated planDefined benefit plan that coordinates Social Security benefits (or contributions) with the benefit (or contribution) formula, thus reducing private retirement benefits based on the amount received through Social Security and lowering employer costs. coordinates Social Security benefits (or contributions) with the private plan’s benefit (or contribution) formula. Integration reduces private retirement benefits based on the amount received through Social Security, thus reducing the cost to employers of the private plan. On the other hand, integration allows employees with higher income to receive greater benefits or contributions, depending on the formula. The scope of this text is too limited to explore the exact mechanism of integrated plans. There are two kinds of plans. The offset method reduces the private plan benefit by a set fraction. This approach is applicable only to defined benefit plans. The second method is the integration-level method. Here, a threshold of compensation, such as the wage base level shown in Chapter 18 "Social Security", is specified, and the rate of benefits or contributions provided below this compensation threshold is lower than the rate for compensation above the threshold. The integration-level method may be used for defined benefit or defined contribution pension plans.

As noted above, defined benefits up to specified levels are guaranteed by the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation (PBGC)Federal agency that ensures the benefits of defined benefit plans up to annual limits in case the pension plan cannot meet its obligations., a federal insurance program somewhat like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) for commercial bank accounts, and like the Guarantee Funds for Insurance. All defined benefit plans contribute an annual fee (or premium) per pension plan participant to finance benefits for members of insolvent terminated plans. The premium amount takes into account, to a degree, the financial soundness of the particular plan, measured by the plan’s unfunded vested benefit. Thus, plans with a greater unfunded vested benefit pay a greater PBGC premium (up to a maximum amount), providing an incentive to employers to adequately fund their pension plans. Despite this incentive, there is national concern about the number of seriously underfunded pension plans insured by the PBGC. If these plans were unable to pay promised retirement benefits, the PBGC would be liable, and PBGC funds may be insufficient to cover the claims. Taxpayers could end up bailing out the PBGC. Careful monitoring of PBGC fund adequacy continues, and funding rules may be tightened to keep the PBGC financially sound.

Defined Benefit Cost Factors

Annual pension contributions and plan liabilities for a defined benefit plan must be estimated by an actuary. (Actuaries with pension specialties are called enrolled actuaries.) The time value of money explained in Chapter 4 "Evolving Risk Management: Fundamental Tools" is used extensively in the computations of pensions. The defined amount of benefits becomes the employer’s obligation, and contributions must equal whatever amount is necessary to fund the obligation. The estimate of cost depends on factors such as salary levels; normal retirement age; current employee ages; and assumptions about mortality, turnover, investment earnings, administrative expenses, and salary adjustment factors (for inflation and productivity). These factors determine estimates of how many employees will receive retirement benefits, how much they will receive, when benefits will begin, and how long benefits will be paid.

Normal costsIn defined benefit plans, the annual amount needed to fund pension benefits during an employee’s working years. reflect the annual amount needed to fund the pension benefit during the employee’s working years. Supplemental costsIn defined benefit plans, the amounts necessary to amortize any past service liability over a period that may vary from ten to thirty years. are the amounts necessary to amortize any past service liability, which is explained above, over a period that may vary from ten to thirty years. Total cost for a year is the sum of normal and supplemental costs. Under some methods of calculation, normal and supplemental costs are estimated as one item. Costs may be estimated for each employee and then added to yield total cost, or a calculation may be made for all participants on an aggregate basis.

Defined benefit plan administration is expensive compared with defined contribution plans because of actuarial expense and complicated ERISA regulations. This explains in part why about 75 percent of the plans established since the passage of ERISA have been defined contribution plans.

Defined Contribution Plans

A defined contribution (DC) planType of pension plan that promises only to contribute an amount to the employee’s separate or individual account; the employee has the investment risk and no assurances of the level of retirement amount; has separate accounts under the control of each participant. is a qualified pension plan in which the contribution amount is defined but the benefit amount available at retirement varies. This is in direct contrast to a defined benefit plan, in which the benefit is defined and the contribution amount varies. As with the defined benefit plan, when the defined contribution plan is initially designed, the employer makes decisions about eligibility, retirement age, integration, vesting schedules, and funding methods.

The most common type of defined contribution plan is the money purchase planIn this simplest of the defined contribution plans, the employer guarantees only the annual contribution to an employee’s retirement account, but not any returns.. This plan establishes an annual rate of employer contribution, usually expressed as a percentage of current compensation; for example, a plan may specify that the employer will contribute 10 percent of an employee’s salary, as shown in the example in Table 21.3 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Money Purchase Plan (2009)". Separate accounts are maintained to track the current balance attributable to each employee, but contributions may be commingled for investment purposes.

Table 21.3 The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Money Purchase Plan (2009)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | Age | Current Salary | Allowed Compensation | Service | Maximum Contribution Allowed | Contribution at 10.00% (3) × 0.10 | Years to Retirement | Future Value of $1 Annuity at 10% | Lump Sum at Retirement (6) × (8) |

| Dr. Slone | 55 | $250,000 | $245,000 | 20 | $49,000 | $24,500 | 10 | 15.937 | $390,457 |

| Diane | 45 | $55,000 | $55,000 | 10 | $49,000 | $5,500 | 20 | 57.274 | $315,007 |

| Jack | 25 | $30,000 | $30,000 | 5 | $30,000 | $3,000 | 40 | 442.58 | $1,327,740 |

The benefit available at retirement varies with the contribution amount, the length of covered service, investment earnings, and retirement age, as you can see in Column 9 of Table 21.3 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Money Purchase Plan (2009)". Some plans allow employees to direct the investment of their own pension funds, offering several investment options. Generally, retirement age has no effect on a distribution received as a lump sum, fixed amount, or fixed period annuity. Retirement age affects the amount of income received only under a life annuity option.

From the perspective of an employer or employee concerned with the adequacy of retirement income, the contributions that typically have the longest time to accumulate with compound investment returns are the smaller ones. They are smaller because the compensation base (to which the contribution percentage is applied) is lowest in an employee’s younger years. This is perhaps the major disadvantage of defined contribution plans. It is also difficult to project the amount of retirement benefit until retirement is near, which complicates planning. In addition, the speculative risk of investment performance (positive or negative returns) is borne directly by employees.

From an employer’s perspective, however, such plans have the distinct advantage of a reasonably predictable level of pension cost because they are expressed as a percentage of current payroll. Because the employer promises only to specify a rate of contribution and prudently manage the plan, actuarial estimates of annual contributions and liabilities are unnecessary. The employer also does not contribute to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, which applies only to defined benefit plans. Most new plans today are defined contribution plans, which is not surprising given their simplicity, lower administrative cost, and limited employer liability for funding.

Other Qualified Defined Contribution Plans

Employers may offer a variety of defined contribution plans other than money purchase plans to assist employees in saving for retirement. These may be the only retirement plans offered by the organization, or they may be offered in addition to a defined benefit plan or a defined contribution money purchase plan, as you can see in Case 2 of Chapter 23 "Cases in Holistic Risk Management". One such defined contribution plan is the target planHybrid age-weighted defined contribution plan in which each employee is targeted to receive the same formula of benefit at retirement, but the benefits are not guaranteed; older employees receive a larger contribution as a percentage of compensation than younger employees since they have less time to accumulate funds to retirement., which is an age-weighted pension plan. Under this plan, each employee is targeted to receive the same formula of benefit at retirement (age sixty-five), but the benefits are not guaranteed. Because older employees have less time to accumulate the funds for retirement, they receive a larger contribution as a percentage of compensation than the younger employees do. The target plan is a hybrid of defined benefits and defined contribution plans, but it is a defined contribution pension plan with the same limits and requirements as defined contribution plans.

Profit-Sharing Plans

All profit-sharing plansIncentive defined contribution plans whereby employers may voluntarily elect to annually distribute a specified portion of company profits among employees in relation to salary. are defined contribution plans. They are considered incentive plans rather than pension plans because they do not have annual funding requirements. Profit-sharing plans provide economic incentives for employees because firm profits are distributed directly to employees. In a deferred profit-sharing planProfit sharing plan in which the employer puts part of its profits in trust for the benefit of employees., a firm puts part of its profits in trust for the benefit of employees. Typically, the share of profit allocated is related to salary; that is, the share each year is the percentage determined by the employee’s salary divided by total salaries for all participants in the plan. Per EGTRRA 2001, the maximum amount of contribution is 25 percent of the total payroll of all employees.

Table 21.4 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Profit Sharing Plan (2009)", featuring again the Slone-Jones Dental Office, shows an allocation of profit sharing should the employer decide to contribute $30,000 to the profit-sharing plan. The allocation is based on the percentage of each employee’s pay from total payroll allowed (see Column 4 in Table 21.4 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Profit Sharing Plan (2009)"). The maximum profits to be shared in 2009 cannot be greater than an allocation of $49,000 for top employees.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009). If the maximum compensation allowed is $245,000 and the maximum contribution is $49,000, in essence the contribution to the account of an employee making $245,000 or more would not be more than 20 percent.

Table 21.4 The Slone-Jones Dental Office: Standard Profit Sharing Plan (2009)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | Current Age | Salary | Maximum Allowed Compensation | Percentage of Pay from Total Adjusted Payroll (3)/330,000 | Allocation of $30,000 Profits (4) × 30,000 |

| Dr. Slone | 55 | $250,000 | $245,000 | 74.24% | $22,272 |

| Diane | 45 | $55,000 | $55,000 | 16.67% | $5,001 |

| Jack | 25 | $30,000 | $30,000 | 9.09% | $2,727 |

| Total | $330,000 | 100.00% | $30,000 |

Employee Stock Ownership Plans

An employee stock ownership plan (ESOP)Special type of profit sharing plan where all investments are in employer’s common stock. is a special form of profit-sharing plan. The unique feature of an ESOP is that all investments are in the employer’s common stock. Proponents of ESOPs claim that this ownership participation increases employee morale and productivity. Critics regard it as a tie-in of human and economic capital in a single firm, which may lead to complete losses when the firm is in trouble. An illustration of the hardship that can occur when employees invest in their company is Enron, a case we noted earlier.

An ESOP represents the ultimate in investment concentration because all contributions are invested in one security. This is distinctly different from the investment diversification found in the typical pension or profit-sharing plan. To alleviate the ESOP investment risk for older employees, employers are required to allow at least three diversified investment portfolios for persons over age fifty-five who also have at least ten years of participation in the plan. Each diversified portfolio contains several issues of nonemployer securities, such as common stocks or bonds. One option might even be a low-risk investment, such as bank certificates of deposit. This allows use of an incentive-type qualified retirement plan without unnecessarily jeopardizing the future retiree’s benefits.

401(k) Plans

Another qualified defined contribution plan is the 401(k) planDefined contribution plan that allows an employee to defer before-tax compensation toward a retirement account, which may be matched or supplemented by employer contributions., which allows employees to defer compensation for retirement before taxes. Refer to the example of deferral in Table 21.5 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: ADP Tests for 401(k) Plan (2009)". As you can see, contributions to a 401(k) plan are limited per the description in Figure 21.2 "Retirement Plans by Type, Limits as of 2009" and Tables 21.6 and 21.7. The total contribution amount to a 401(k) plan, by both employee and employer, cannot exceed $49,000 or 100 percent of the employee’s income. In 2009, the deferral by the employee cannot exceed $16,500, unless the employee is over age fifty.Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “IRS Announces Pension Plan Limitations for 2009,” IR-2008-118, October 16, 2008, http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=187833,00.html (accessed April 17, 2009).

Table 21.5 The Slone-Jones Dental Office: ADP Tests for 401(k) Plan (2009)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | Current Age | Salary | Allowable Compensation | Voluntary 401(k) Contribution | Contribution as a Percentage of Compensation (4)/(3) |

| Dr. Slone | 55 | $250,000 | $245,000 | $16,500 | 5.92% |

| Diane | 45 | $55,000 | $55,000 | 3,000 | 5.45% |

| Jack | 25 | $30,000 | $30,000 | 1,200 | 4.00% |

| ADP Test 1: Average Jack’s and Diane’s contributions ([5.45% + 4.00%]/2) = 4.73%; multiply 4.73% × 1.25 = 5.91%. This figure is less than Dr. Slone’s contribution. Failed. | |||||

| ADP Test 2: 4.73% × 2 = 9.46%. 4.73% + 2 = 6.73%. The lesser of these is more than Dr. Slone’s contribution. Passed. | |||||

Table 21.6 Limits for 401(k), 403(b) [also Roth 401(k) and 403(b)], and 457 Plans

| Taxable Year | Salary Reduction Limit |

|---|---|

| 2005 | $14,000 |

| 2006 | $15,000 |

| 2007 | $15,500 |

| 2008 | $15,500 |

| 2009 | $16,500 |

Table 21.7 Additional Limits for Employees over 50 Years of Age for 401(k), 403(b) [also Roth 401(k) and 403(b)], and 457 Plans

| Taxable Year | Additional Deferral Limit (Age 50 and Older) |

|---|---|

| 2005 | $4,000 |

| 2006 | $5,000 |

| 2007 | $5,000 |

| 2008 | $5,000 |

| 2009 | $5,500 |

| 2010 | Indexed to inflation |

To receive the tax credits for 401(k), employers have to pass the average deferral percentage (ADP) test, unless they either (1) match 100 percent of the employee contribution up to 3 percent of compensation and 50 percent of the employee contribution between 3 percent and 5 percent of compensation or (2) make a nonelective (nonmatching) contribution for all eligible nonhighly-compensated employees equal to at least 3 percent of compensation. These employers’ contributions are considered a safe harbor. The ADP test is shown in Table 21.5 "The Slone-Jones Dental Office: ADP Tests for 401(k) Plan (2009)" for a hypothetical elective deferral of the employees of the Slone-Jones Dental Office.

As you can see, the ADP has two parts:

- Average the deferral percentages of the nonhighly-compensated employees. Multiply this figure by 1.25. Is the result greater than the average for the highly compensated employees? If it is, the employer passed the test. If it is not, proceed to the next test.

- Take the average of the deferral percentages of nonhighly-compensated employees. Double this percentage or add two percentage points, whichever is less. Is the result greater than the average for the highly compensated employees?