This is “Risks Related to the Job: Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Compensation”, chapter 16 from the book Enterprise and Individual Risk Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 16 Risks Related to the Job: Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Compensation

Workers’ compensation is a state-mandated coverage that is exclusively related to the workplace. Unemployment compensation is also a mandated program required of employers. Both are considered social insurance programs, as is Social Security. Social Security is featured in Chapter 18 "Social Security" as a foundation program for employee benefits (covered in Chapter 19 "Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance" through Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management"). Social insurance programs are required coverages as a matter of law. The programs are based only on the connection to the labor force, not on need. Both workers’ compensation and unemployment compensation are part of the risk management of businesses in the United States. The use of workers’ compensation as part of an integrated risk program is featured in Case 3 of Chapter 23 "Cases in Holistic Risk Management".

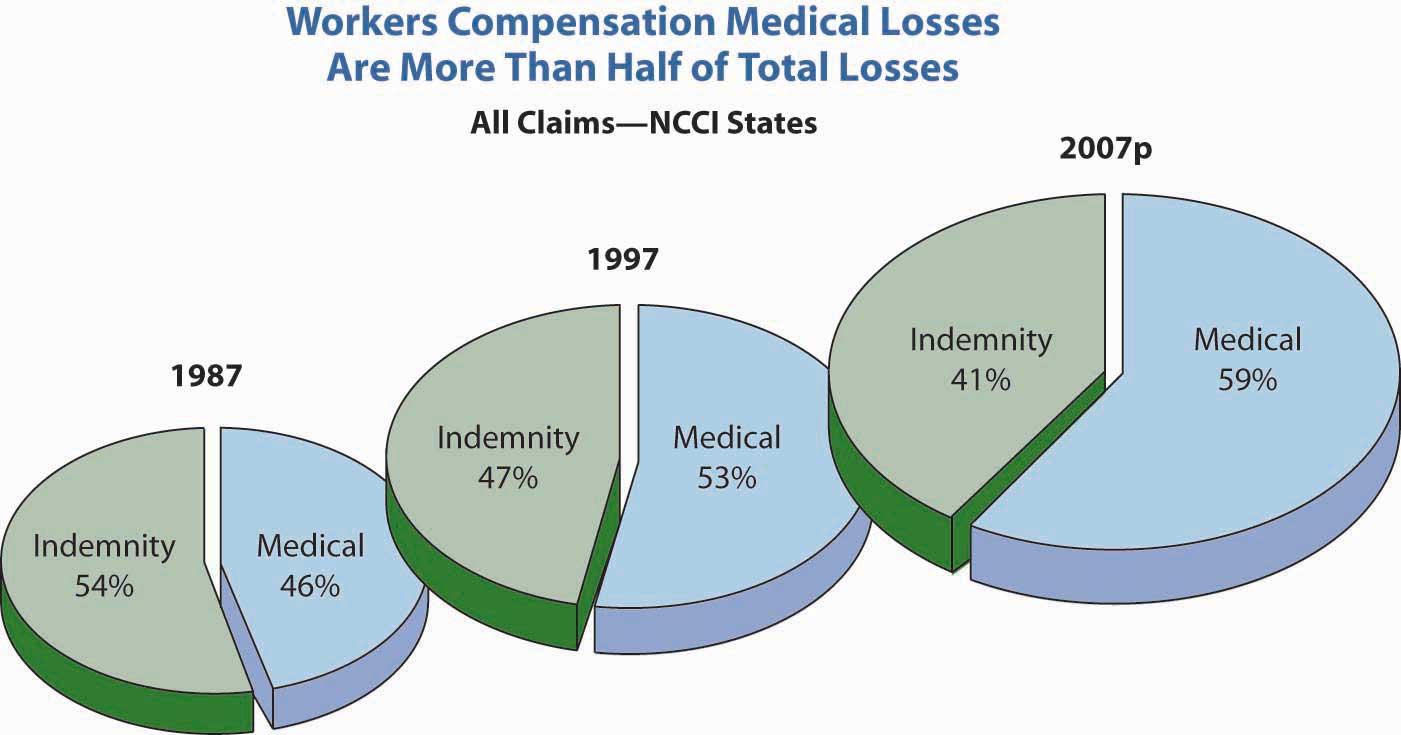

Workers’ compensation was one of the coverages that helped the families who lost their breadwinners in the attacks of September 11, 2001. New York City and the state of New York suffered their largest-ever loss of human lives. Because most of the loss of life occurred while the employees were at work, those injured received medical care, rehabilitation, and disability income under the New York workers’ compensation system, and families of the deceased received survivors’ benefits. The huge payouts raised the question of what would happen to workers’ compensation rates. The National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI) predicted a grim outlook then, but by 2005, conditions improved as frequency of losses declined and the industry’s reserves increased.Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, Chief Actuary, NCCI, Inc., “State of the Line,” May 8, 2008; Orlando, Florida, 2008; NCCI Holdings, Inc. The workers’ compensation line has maintained this strong reserve position and has been helped by a continual downward trend in loss frequency. Consequently, the industry reported a combined ratio of 93 percent in 2006 and projects a 99 percent combined ratio for 2007. This indicates positive underwriting results. However, medical claims severity (in contrast to frequency) has continued to grow, as shown in Figure 16.1 "Changes in the Distribution of Medical versus Indemnity Claims in Workers’ Compensation*".

Workers’ compensation is considered a social insurance program. Another social insurance program is the unemployment compensation offered in all the states. This chapter includes a brief explanation of this program as well. To better understand how workers’ compensation and unemployment compensation work, this chapter includes the following:

- Links

- Workers’ compensation laws and benefits

- How benefits are provided

- Workers’ compensation issues

- Unemployment compensation

Figure 16.1 Changes in the Distribution of Medical versus Indemnity Claims in Workers’ Compensation*

* 2007p: Preliminary based on data valued as of December 31, 2007;

1987, 1997: Based on data through December 31, 2006, developed to ultimate;

based on the states where NCCI provides rate-making services, excludes the effects of deductible policies

Source: Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), Inc. Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, Accessed March 28, 2009, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf. © 2008 NCCI Holdings, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

Links

At this point in our study, we look at the coverage employers provide for you and your family in case you are hurt on the job (workers’ compensation) or lose your job involuntarily (unemployment compensation). As noted above, these coverages are mandatory in most states. Workers’ compensation is not mandatory in New Jersey and Texas (although most employers in these states provide it anyway). In later chapters, you will see the employer-provided group life, health, disability, and pensions as part of noncash compensation programs. These coverages complete important parts of your holistic risk management. You know that, at least for work-related injury, you have protection, and that if you are laid off, limited unemployment compensation is available to you for six months. These coverages are paid completely by the employer; the rates for workers’ compensation are based on your occupational classification.

In some cases, the employer does not purchase workers’ compensation coverage from a private insurer but buys it from a state’s monopolistic fund or self-insures the coverage. For unemployment compensation, the coverage, in most cases, is provided by the states.Exceptions are taxing governmental entities, such as the school districts in Texas, that may be allowed to self-insure unemployment compensation. They have a pool administered by the Texas Association of School Boards. Regardless of the method of obtaining the coverage, you are assured by statutes to receive the benefits.

As with the coverages discussed in Chapter 13 "Multirisk Management Contracts: Homeowners" to Chapter 15 "Multirisk Management Contracts: Business", external market conditions are a very important indication of the cost of coverage to your employer. When rates increase dramatically, many employers will opt to self-insure and use a third-party administrator (TPA) to manage the claims. In workers’ compensation, loss control and safety engineering are important parts of the risk management process. One of the causes of loss is ergonomics, particularly as related to computers. See the box “Should Ergonomic Standards Be Mandatory?” for a discussion. You would like to minimize your injury at work, and your employer is obligated under federal and state laws to secure a safe workplace for you.

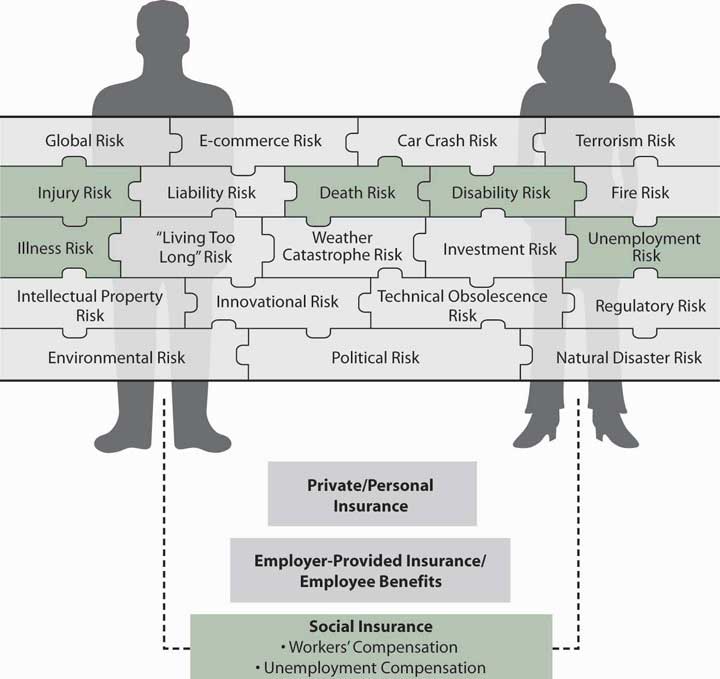

Thus, in your pursuit of a holistic risk management program, workers’ compensation coverage is an important piece of the puzzle that completes your risk mitigation. The coverages you receive are only for work-related injuries. What happens if you are injured away from work? This will be discussed in later chapters. One trend is integrated benefits, in which the employer integrates the disability and medical coverages of workers’ compensation with voluntary health and disability insurance. Integrated benefits are part of the effort to provide twenty-four-hour coverage regardless of whether an injury occurred at work or away from work. Currently, nonwork-related injuries are covered for medical procedures by the employer-provided health insurance and for loss of income by group disability insurance. Integrating the benefits is assumed to prevent double dipping (receiving benefits under workers’ compensation and also under health insurance or disability insurance) and to ensure security of coverage regardless of being at work or not. (See the box “Integrated Benefits: The Twenty-Four-Hour Coverage Concept.”) Health and disability coverages are provided voluntarily by your employer, and it is your responsibility to seek individual coverages when the pieces that are offered are insufficient to complete your holistic risk management. Figure 16.2 "Links between Holistic Risk Pieces and Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Compensation" shows how your holistic risk pieces relate to the risk management parts available under workers’ compensation and unemployment compensation.

Figure 16.2 Links between Holistic Risk Pieces and Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Compensation

16.1 Workers’ Compensation Laws and Benefits

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on the following:

- History of workers’ compensation

- Legal enactment of workers’ compensation

- Benefits provided under workers’ compensation

Each state and certain other jurisdictions, such as the District of Columbia and other U.S. territories, has a workers’ compensationA system to enforce a series of state laws that requires employers to pay workers for their work-related injuries and illnesses with no relationship to who caused the injury or illness. system to enforce a series of state laws that requires employers to pay workers for their work-related injuries and illnesses with no relationship to who caused the injury or illness.

History and Purpose

In the nineteenth century, before implementation of workers’ compensation laws in the United States, employees were seldom paid for work-related injuries. A major barrier to payment was that a worker had to prove an injury was the fault of his or her employer to recover damages. The typical employee was reluctant to sue his or her employer out of fear of losing the job. For the same reason, fellow workers typically refused to testify on behalf of an injured colleague about the circumstances surrounding an accident. If the injured employee could not prove fault, the employer had no responsibility. The injured employee’s ability to recover damages was hindered further by the fact that even a negligent employer could use three common law defensesThe three arguments that employers utilized to avoid assuming responsibility for employees’ work-related injuries prior to the establishment of of workers’ compensation laws: the fellow-servant rule, the assumption of risk doctrine, and the contributory negligence doctrine. to disavow liability for workers’ injuries: the fellow-servant rule, the doctrine of assumption of risk, and the doctrine of contributory negligence.

Under the fellow-servant ruleDefense under which an employee injured as a result of the conduct of a fellow worker cannot recover damages from the employer., an employee who was injured as a result of the conduct of a fellow worker could not recover damages from the employer. The assumption of risk doctrineDefense providing that an employee who knew, or should have known, of unsafe conditions of employment assumed the risk by remaining on the job. provided that an employee who knew, or should have known, of unsafe conditions of employment assumed the risk by remaining on the job. Further, it was argued that the employee’s compensation recognized the risk of the job. Therefore, he or she could not recover damages from the employer when injured because of such conditions. If an employee was injured through negligence of the employer but was partly at fault, the employee was guilty of contributory negligenceDefense arguing that an employee was injured through negligence of the employer but was also partly at fault.. Any contributory negligence, regardless of how slight, relieved the employer of responsibility for the injury.

These defenses made recovery of damages by injured employees nearly impossible and placed the cost of work-related injuries on the employee. As a result, during the latter part of the nineteenth century, various employer liability lawsPortion of a worker’s compensation policy that protects against potential liabilities not within the scope of the workers’ compensation law, yet arising out of employee injuries. were adopted to modify existing laws and improve the legal position of injured workers. The system of negligence liability was retained, however, and injured employees still had to prove that their employer was at fault to recover damages.

Even with modifications, the negligence system proved costly to administer and inefficient in protecting employees from the financial burdens of workplace injuries.A counterargument is postulated in D. Edward and Monroe Berkowitz, “Challenges to Workers’ Compensation: A Historical Analysis,” in Workers’ Compensation Adequacy, Equity & Efficiency, ed. John D. Worral and David Appel (Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 1985). The authors contend that workers were becoming successful in suing employers. Thus, workers’ compensation developed as an aid to employers in limiting their responsibilities to employees. The need for more extensive reform was recognized, with many European countries instituting social insurance programs during the latter half of the 1800s. Beginning with Wisconsin in 1911,For a detailed history of workers’ compensation laws, see the Encyclopedia of Economic and Business History, http://eh.net/encyclopedia/fishback.workers.compensation.php//eh.net/encyclopedia/. U.S. jurisdictions developed the concept of workers’ compensation that compensated workers without the requirement that employers’ negligence must be proved (that is, with strict employer liability). Costs were borne directly by employers (generally in the form of workers’ compensation insurance premiums) and indirectly by employees who accepted lower wages in exchange for benefits. To the extent, if any, that total labor costs were increased, consumers (who benefit from industrialization) shared in the burden of industrial accidents through higher prices for goods and services. Employees demanded higher total compensation (wages plus benefits) to engage in high-risk occupations, resulting in incentives for employers to adopt safety programs. By 1948, each jurisdiction had similar laws.

In compromising between the interests of employees and those of employers, the originators of workers’ compensation systems limited the benefits available to employees to some amount less than the full loss. They also made those benefits the sole recourse of the employee against the employer for work-related injuries. This give-and-take of rights and duties between employers and employees is termed quid pro quo(Latin phrase meaning “this for that”)—give-and-take of rights and duties between employers and employees. (Latin for “this for that”). The intent was for the give and take to have an equal value, on average. You will see in our discussion of current workers’ compensation issues that some doubt exists as to whether equity has been maintained. An exception to the sole recourse concept exists in some states for the few employees who elect, prior to injury, not to be covered by workers’ compensation. Such employees, upon injury, can sue their employer; however, the employer in these instances retains the three defenses described earlier.

In addition to every state and territory having a workers’ compensation law, there are federal laws applicable to longshore workers and harbor workers, to nongovernment workers in the District of Columbia, and to civilian employees of the federal government. Workers’ compensation laws differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but they all have the purpose of ensuring that injured workers and their dependents will receive benefits without question of fault.

Integrated Benefits: The Twenty-Four-Hour Coverage Concept

Are your wrists painful? Or numb? (If you think about it long enough, you’ll convince yourself they’re one or the other.) Perhaps you have a repetitive stress injury or carpal tunnel syndrome. Maybe it’s now painful enough that you need to take a few days off. But wait—you use a computer at work, so this could be a work-related injury. Better go talk to the risk manager about filing a workers’ compensation claim. But wait—you spend hours at home every night playing computer games. If this is an off-hours injury, you should call your health maintenance organization (HMO) for an appointment with your primary care physician so you can arrange for short-term disability. But wait—when your boss is not looking, you surf the Internet at work. What do you do?

If you worked for Steelcase, Inc., an office-furniture manufacturer based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, your wrists might still hurt, but you would not have to worry about who to call. Steelcase used to handle its medical benefits like most companies do: the risk management department handled workers’ compensation; the human resources department handled health insurance, short-term disability, and long-term disability; and four separate insurers provided the separate coverages. Several events caused top management to rethink this disintegrated strategy: rising medical costs, a slowdown in the economy that forced a look at cost-saving measures, and the results of a survey showing that employees simply did not understand their benefits. “The employees hammered us in terms of not understanding who to call or what they get,” Steelcase manager Libby Child told Employee Benefit News in June 2001.

In 1997, Steelcase became one of the first U.S. companies to implement an integrated benefits program. It combined long- and short-term disability, workers’ compensation, medical case management, and Family and Medical Leave Act administration, and outsourced the record-keeping duties. Now a disabled employee—whether the injury is work-related or not—can make one phone call and talk to a representative who collects information, files any necessary claims, and assigns the worker to a medical case manager. The case manager ensures that the employee is receiving proper medical treatment and appropriate benefits and helps him or her return to work as soon as possible.

The integrated plan has been a hit with employees, who like the one-call system, and with managers because lost-time days decreased by one-third after the program was implemented. Steelcase’s financial executives are happy, too: the combined cost of short-term disability, long-term disability, and workers’ compensation dropped 13 percent in the program’s first three years.

In California, however, results with integrated benefits have been mixed. The California state legislature authorized three-year pilot programs in four counties to study the effectiveness of twenty-four-hour health care in the early 1990s, a time when workers’ compensation premiums were inordinately expensive for employers. By the time the programs were under way, these costs had become more competitive. Thus, most employers viewed a change to integrated benefits as simply too risky in relation to the traditional workers’ compensation system. Nonetheless, then California Insurance Commissioner (and current California Lieutenant Governor) John Garamendi championed the concept of integrated benefits. Garamendi maintains that placing workers’ compensation and health coverage under managed care has the potential to save California $1 billion through reductions in administrative and legal expenses, fraud, and medical costs.

With Steelcase and other pioneers proving the success of integrated benefits, it is a wonder that all companies have not jumped on the bandwagon. Many are, but there are still some obstacles to overcome:

- The shift from paper record keeping to computer databases raises concerns over privacy.

- Risk managers and human resources personnel may have turf wars over the combination of their duties.

- To fully integrate and to be able to generate, meaningful data, all computer systems must be compatible and their operators trained; however, human resource departments and the treasurer (where risk management resides) may not have the same systems.

- Workers’ compensation is provided by property/casualty insurers, while health and disability are provided by life/health insurers, so integration may be complicated.

- Regulations vary widely for workers’ compensation and employee benefits.

In the past few years, many companies, large and small, have taken the leap toward integrating benefits. Recent converts include Pacific Bell; San Bernardino County in California; Pitney Bowes; and even an insurance company, Nationwide. Several organizations specializing in the twenty-four-hour coverage concept have also emerged. Notably, the Integrated Benefits Institute (IBI) merges health, absenteeism, and disability management under one banner and provides consulting services. Integrated Benefits LLC is another brokerage firm in this area operating in the Carolinas, and United 24 has produced success bringing together managed care, workers’ compensation, and disability insurance for Wisconsin employers. For any business that wants to reduce sick time off and disability benefits—which cost the average company 14.3 percent of payroll—the issue of integrating benefits is not “whether” but “when.”

Sources: Diana Reitz, “It’s Time to Resume the 24-Hour Coverage Debate,” National Underwriter Property & Casualty/Risk & Benefits Management Edition, February 8, 1999; Annmarie Geddes Lipold, “Benefit Integration Boosts Productivity and Profits,” Workforce.com, accessed March 31, 2009, http://www.workforce.com/section/02/feature/23/36/89/; Karen Lee, “Pioneers Return Data on Integrated Benefits,” Employee Benefit News, June 2001; Lee Ann Gjertsen, “Brokers Positive on Integrated Benefits,” National Underwriter, Property & Casualty/Risk & Benefits Management Edition, July 7, 1997; Leo D. Tinkham, Jr., “Making the Case for Integrated Disability Management,” National Underwriter, Life & Health/Financial Services Edition, May 13, 2002; Phyllis S. Myers and Etti G. Baranoff, “Workers’ Compensation: On the Cutting Edge,” Academy of Insurance Education, Washington, D.C., instructional video with supplemental study guide, video produced by the Center for Video Education, 1997.

Coverage

Coverage under workers’ compensation is either inclusive or exclusive. Further, it is compulsory or elective, depending on state law. A major feature is that only injuries and illnesses that “arise out of and in the course of employment” are covered.

Inclusive or Exclusive

Inclusive lawsLaws that list all the types of employment covered under workers’ compensation. list all the types of employment that are covered under workers’ compensation; exclusive lawsLaws that cover all the types of employment under workers’ compensation except those that are excluded. cover all the types of employment under workers’ compensation except those that are excluded. Typically, domestic service and casual labor (for some small jobs) are excluded. Agricultural workers are excluded in nineteen jurisdictions, whereas their coverage is compulsory in twenty-seven jurisdictions and entirely voluntary in four jurisdictions. Some states limit coverage to occupations classified as hazardous. The laws of thirty-nine states apply to all employers in the types of employment covered; others apply only to employers with more than a specified number of employees. Any employer can comply voluntarily.

Compulsory or Elective

In all but two states, the laws regarding workers’ compensation are compulsory. In these two states (New Jersey and Texas) with elective lawsState laws providing that either the employer or the employee may elect not to be covered under workers’ compensation law., either the employer or the employee can elect not to be covered under workers’ compensation law. An employer who opts out loses the common law defenses discussed earlier. If the employer does not opt out but an employee does, the employer retains those defenses as far as that employee is concerned. If both opt out, the employer loses the defenses. It is unusual for employees to opt out because those who do must prove negligence in order to collect and must overcome the employer’s defenses.

An employer who does not opt out must pay benefits to injured employees in accordance with the requirements of the law, but that is the employer’s sole responsibility. Thus, an employee who is covered by workers’ compensation cannot sue his or her employer for damages because workers’ compensation is the employee’s sole remedyProvides that employees cannot (in most circumstances) sue their employers for work-related injuries, regardless of fault, when covered by workers’ compensation. (also called exclusive remedy). (In fact, workers’ compensation is losing its status as the employee’s sole remedy against the employer. Later in this chapter, we will discuss some of the current methods used by employees to negate the exclusive remedy rule.) By coming under the law, the employer avoids the cost of litigation and the risk of having to pay a large judgment in the event an injured employee’s suit for damages is successful.

In Texas, 65 percent of employers opted to stay in the system despite the fact that workers’ compensation is not mandatory.Daniel Hays, “Despite Option, More Texas Firms Offer Comp,” National Underwriter Online News Service, February 1, 2002. The results were obtained through a survey of 2,808 employers between August and October 2001 following the passage of a measure that outlawed the use of preinjury liability waivers by employees. It is likely that as insurance rates rise, more companies will opt to stay out of the system. Nearly all employers that opt out reduce their likelihood of being sued by providing an alternative employee benefit plan that includes medical and disability income benefits as well as accidental death and dismemberment benefits for work-related injuries and illnesses.Employee benefits are discussed in Chapter 19 "Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance" to Chapter 20 "Employment-Based Risk Management (General)". Alternative coverage never exactly duplicates a state’s workers’ compensation benefits. In addition, the employer purchases employer’s liability insurance to cover the possibility of being sued by injured employees who are not satisfied with the alternative benefits.

Proponents of an opt-out provision argue that competition from alternative coverage provides market discipline to lower workers’ compensation insurance prices. Furthermore, greater exposure to common law liability suits may encourage workplace safety. Opponents see several drawbacks of opt-out provisions:

- Some employers may fail to provide medical benefits or may provide only modest benefits, resulting in cost shifting to other segments of society.

- The right of the employee to sue may be illusory because some employers may have few assets and no liability insurance.

- Employees may be reluctant to sue the employer, especially when the opportunity to return to work exists or if family members may be affected.

- Safety incentives may not be enhanced for employers with few assets at risk.

Covered Injuries

To limit benefits to situations in which a definite relationship exists between an employee’s work and the injury, most laws provide coverage only for injuries “arising out of and in the course of employment.” This phrase describes two limitations. First, the injury must arise out of employment, meaning that the job environment was the cause. For example, the family of someone who has a relatively stress-free job but dies of cardiac arrest at work would have trouble proving the work connection and therefore would not be eligible for workers’ compensation benefits. On the other hand, a police officer or firefighter who suffers a heart attack (even while not on duty) is presumed in many states to have suffered from work-related stress.

The second limitation on coverage is that the injury must occur while in the course of employment. That is, the loss-causing event must take place while the employee is on the job in order to be covered by workers’ compensation. An employee injured while engaged in horseplay, therefore, might not be eligible for workers’ compensation because the injury did not occur while the employee was “in the course of employment.” Likewise, coverage does not apply while traveling the normal commute between home and work. Along these same lines of reasoning, certain injuries generally are explicitly excluded, such as those caused by willful misconduct or deliberate failure to follow safety rules, those resulting from intoxication, and those that are self-inflicted.

Subject to these limitations, all work-related injuries are covered, even if they are due to employee negligence. In addition, every state provides benefits for occupational diseaseAn injury arising out of employment and due to causes and conditions characteristic of, and peculiar to, the particular trade, occupation, process, or employment, and excluding all ordinary diseases to which the general public is exposed., which is defined in terms such as “an injury arising out of employment and due to causes and conditions characteristic of, and peculiar to, the particular trade, occupation, process or employment, and excluding all ordinary diseases to which the general public is exposed.”Various concepts and statistics in this chapter are based on research described in S. Travis Pritchett, Scott E. Harrington, Helen I. Doerpinghaus, and Greg Niehaus, An Economic Analysis of Workers’ Compensation in South Carolina (Columbia, SC: Division of Research, College of Business Administration, University of South Carolina, 1994). Some states list particular diseases covered, whereas others simply follow general guidelines.

Benefits

Workers’ compensation laws provide for four types of benefits: medical, income replacement, survivors’ benefits, and rehabilitation.

Medical

All laws provide unlimited medical care benefits for accidental injuries. Many cases do not involve large expenses, but it is not unusual for medical bills to run into many thousands of dollars. Medical expenses resulting from occupational illnesses may be covered in full for a specified period of time and then terminated. Unlike nonoccupational health insurance, workers’ compensation does not impose deductibles and coinsurance to create incentives for individuals to control their demand for medical services.

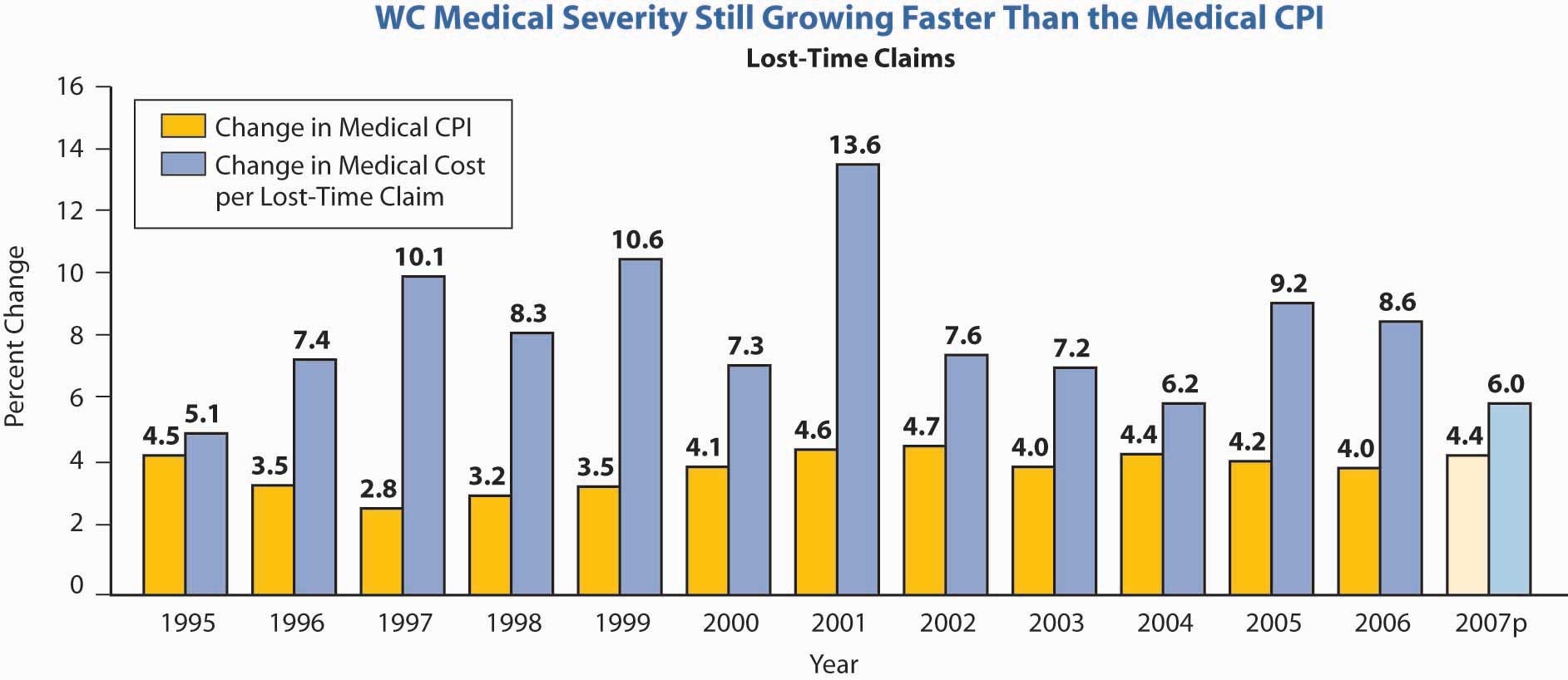

When you study health care in Chapter 21 "Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management" and Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management", you will become very familiar with managed care. To save on the escalating costs of medical care in workers’ compensation, the medical coverage also uses managed care. Briefly, managed care limits the choice of doctors. The doctors’ decisions are reviewed by the insurer, and many procedures require preapproval. Along with many other states, Texas passed legislation in 2005 that incorporates managed care in the workers’ compensation system.Steve Tuckey, “Texas Legislature OKs Comp Reform,” National Underwriter Online News Service, May 31, 2005. Under these systems, doctors who take care of injured employees under workers’ compensation coverage are asked to try to get the employees back to work as soon as possible. The return-to-work objective is to ensure employees’ presence at work under any capacity, thus incurring less workers’ compensation losses. The industry is attempting to monitor itself for managing the care in a more cost-saving manner.Dale Chadwick and Peter Rousmaniere, “Managing Workers’ Comp: The Workers’ Compensation Managed-Care Industry Is Doing a Better Job of Monitoring Itself, but It Needs to Figure out What to Do with the Information,” Best’s Review, November 2001, http://www3.ambest.com/Frames/FrameServer.asp?AltSrc=23&Tab=1&Site=bestreview&refnum=13969 (accessed March 31, 2009). One area that causes major increases in the workers’ compensation rate is the cost of drugs. In 2006, medical costs per lost time claim increased 8.6 percent over the prior year, compared to a 4 percent increase in the medical consumer price index (CPI).Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance, Inc. (NCCI) Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf (accessed March 28, 2009). Figure 16.3 "Workers’ Compensation Medical Severity*" shows the costs of medical claims under workers’ compensation from 1995 to 2007. As you can see, the severity of medical claims (losses per claim) has outpaced the medical CPI every year since.

Figure 16.3 Workers’ Compensation Medical Severity*

* 2007p: Preliminary based on data valued as of December 31, 2007;

Medical severity 1995–2006: Based on data through December 31, 2006, developed to ultimate;

based on the states where NCCI provides ratemaking services, excludes the effects of deductible policies

Source: Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), Inc. Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, Accessed March 28, 2009, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf.

© 2008 NCCI Holdings, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

Income Replacement

All workers’ compensation laws provide an injured employee with a weekly income while disabled as the result of a covered injury or disease. Income replacement benefits under workers’ compensation are commonly referred to by industry personnel as indemnity benefitsReimburse insureds for actual costs incurred for health care up to covered limits in traditional fee-for-service plans.. The amount and duration of indemnity payments depend on the following factors:

- Whether the disability is total or partial, and temporary or permanent

- The employee’s compensation

- Each state’s maximum duration of benefits

- The waiting period

- Cost-of-living adjustments

Degree and Length of Disability

Total disability refers to the condition of an employee who misses work because he or she is unable to perform any of the important duties of the occupation. Partial disability, on the other hand, means the injured employee can perform some but not all, of the duties of his or her occupation. In either case, disability may be permanent or temporary. Permanent total disability means the injured person is not expected to be able to work again. Temporary total disability means the injured employee is expected to be able to return to work at some future time.The amount of weekly income benefits is the same for both permanent and temporary total disability.

Partial disability may be either temporary or permanent. Temporary partial payments are most likely to be made following a period of temporary total disability. A person who can perform some but not all work duties qualifies for temporary partial benefitsPayments made to an injured employee can perform some, but not all, work duties.. Such benefits are based on the difference between wages earned before and after an injury. They account for a minor portion of total claim payments.

Most laws specify that the loss of certain body parts constitutes permanent partial disabilityThe loss of certain body parts.. Benefits expressed in terms of the number of weeks of total disability payments are usually provided in such cases and are known as scheduled injuriesInjuries covered under permanent partial disability.. For example, the loss of an arm might entitle the injured worker to two hundred weeks of total disability benefits; the loss of a finger might entitle him or her to thirty-five weeks of benefits. No actual loss of time from work or income is required because the assumption is that loss of a body part causes a loss of future income.

Of the fifteen largest classes of occupation, clerical jobs see the highest number of lost time claims. However, this by far the largest occupational class by payroll. The actual frequency of claims as a percentage of payroll dollars is among the lowest for clerical workers. Historically, trucking has seen the highest frequency of claims by payroll. Overall, the frequency of lost-time-only claims has declined, which is the good news in the workers’ compensation field. The largest drop is in the convalescent/nursing home claims. The least decline is in the drivers/chauffeurs and college professional classifications.

Amount of Benefits

Weekly benefits for death, disability, and (often) disfigurement are primarily based on the employee’s average weekly wage (average earned income per week during some specified period prior to disability) multiplied by a replacement ratio, expressed as a percentage of the average weekly wage. Jurisdictions also set minimum and maximum weekly benefits.

The replacement percentage for disability benefits ranges from sixty in one jurisdiction to seventy in two others, but in most jurisdictions it is 66⅔. The percentage reflects the intent to replace income after taxes and other work-related expenses because workers’ compensation benefits are not subject to income taxation. In Virginia, for example, the compensation rate is adjusted each year on July 1. Effective July 1, 2008, the maximum rate was $841, and the minimum rate was $210.25. The cost of living increase will be 4.2 percent, effective October 1, 2008.See Virginia Workers’ Compensation Commission Web site at http://www.vwc.state.va.us/ (accessed March 28, 2009). In Texas, the maximum temporary income benefit for 2009 is $750 and the minimum is $112.See Texas Workers’ Compensation Commission Web site at http://www.twcc.state.tx.us (accessed March 28, 2009) for the details regarding the Texas benefits. Each state workers’ compensation commission has a Web site that shows its benefit amounts. Twenty jurisdictions lower their permanent partial maximum payment per week below their maximum for total disability. For these jurisdictions, the average permanent partial maximum is 66⅔ percent of their total disability maximum. With respect to death benefits, thirty-one jurisdictions use 66⅔ percent in determining survivors’ benefits for a spouse only; five of these use a higher percentage for a spouse plus children. The range of survivors’ benefits for a spouse plus children ranges from 60 percent in Idaho to 75 percent in Texas. Examples of Texas benefits calculations are demonstrated in hypothetical incomes in Table 16.1 "Hypothetical Examples of Texas Workers’ Compensation Income Calculations" A to D. In Texas, temporary income benefits equal 70 percent of the difference between a worker’s average weekly wage and the weekly wage after the injury. If a worker’s average weekly wage was $500, and an injury caused the worker to lose all of his or her income, temporary income benefits would be $350 a week.

Table 16.1 Hypothetical Examples of Texas Workers’ Compensation Income Calculations

| A. Calculation of Temporary Income Benefits | |

| Average weekly wage (hypothetical) | $400 |

| Less: wage after injury | 0 |

| Equals | $400 |

| Temporary income benefit (70 percent the “equals” amount) | $280 |

| B. Calculation of Supplemental Income Benefits | |

| Average weekly wage | $400 |

| 80 percent of weekly wage | $320 |

| Less: the current wage | 0 |

| Equals | $320 |

| Supplemental benefit (80 percent of the “equals” amount) | $256 |

| C. Calculation of Lifetime Income Benefits for Disability with a Loss of Limb | |

| Average weekly wage | $400 |

| Lifetime income benefit (75 percent of weekly wage) | $300 |

| D. Calculation of Death Benefits | |

| Average weekly wage | $400 |

| Death benefit (75 percent of weekly wage) | $300 |

The next example is demonstrated in Table 16.1 "Hypothetical Examples of Texas Workers’ Compensation Income Calculations" B for temporary income after returning to work part-time. In Texas, an injured worker may get lifetime income benefits if the worker has an injury or illness that results in the loss of the hands, feet, or eyesight, or if the worker meets the conditions of the Texas Workers’ Compensation Act. Table 16.1 "Hypothetical Examples of Texas Workers’ Compensation Income Calculations" C provides an example of benefits for lifetime in such a case.

Duration of Benefits

In thirty-nine jurisdictions, no limit is put on the duration of temporary total disability. Nine jurisdictions, however, allow benefits for less than 500 weeks; two specify a 500-week maximum. The limits are seldom reached in practice because the typical injured worker’s condition reaches “maximum medical improvement,” which terminates temporary total benefits earlier. Maximum medical improvement is reached when additional medical treatment is not expected to result in improvement of the person’s condition.

In forty-three jurisdictions, permanent total benefits are paid for the duration of the disability and/or lifetime. These jurisdictions generally do not impose a maximum dollar limit on the aggregate amount that can be paid.

Waiting Periods

Every jurisdiction has a waiting period before indemnity payments (but not medical benefits) for temporary disability can begin; the range is from three to seven days. The waiting period has the advantages of giving a financial incentive to work, reducing administrative costs, and reducing the cost of benefits. If disability continues for a specified period (typically, two to four weeks), benefits are retroactive to the date disability began. Moral hazard is created among employees who reach maximum medical improvement just before the time of the retroactive trigger. Some employees will malinger long enough to waive the waiting period. Hawaii does not allow retroactive benefits.

Cost-of-Living Adjustment

Fifteen jurisdictions have an automatic cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for weekly benefits. In some cases, the COLA takes effect only after disability has continued for one or two years. Because benefit rates are usually set by law, those rates in jurisdictions that lack automatic increases for permanent benefits become out of date rapidly during periods of inflation.

Survivors’ Benefits

In the event of a work-related death, all jurisdictions provide survivor income benefits for the surviving spouse and dependent children, as well as a burial allowance. The survivor income benefit for a spouse plus children is typically (in thirty jurisdictions) 66⅔ percent of the worker’s average weekly wage. Several jurisdictions provide additional income for one child only. Table 16.1 "Hypothetical Examples of Texas Workers’ Compensation Income Calculations" D provides an example of the death benefits in Texas. Burial benefits pay up to $2,500 of the worker’s funeral expenses. Burial benefits are paid to the person who paid the worker’s funeral expenses. The death benefits in New York were discussed earlier in this chapter. In the example case for Texas, the replacement of lost income is 75 percent, as shown in Table 16.1 "Hypothetical Examples of Texas Workers’ Compensation Income Calculations" D.

Rehabilitation

Most people who are disabled by injury or disease make a complete recovery with ordinary medical care and return to work able to resume their former duties. Many workers, however, suffer disability of such a nature that something more than income payments and ordinary medical services is required to restore them, to the greatest extent possible, to their former economic and social situation. Rehabilitation is the process of accomplishing this objective and involves the following:

- Physical-medical attention in an effort to restore workers as nearly as possible to their state of health prior to the injury

- Vocational training to enable them to perform a new occupational function

- Psychological aid to help them adjust to their new situation and be able to perform a useful function for society

About one-fourth of the workers’ compensation laws place this responsibility on the employer (or the insurer, if applicable). Most of the laws require special maintenance benefits to encourage disabled workers to cooperate in a rehabilitation program. Nearly all states reduce or stop income payments entirely to workers who refuse to participate.

Key Takeaways

In this section you studied the history of workers’ compensation, related laws, and benefits provided:

- Traditionally, employers used three common law defenses against liability for injury to workers: the fellow-servant rule, assumption of risk doctrine, and contributory negligence doctrine.

- Workers’ compensation was developed as a compromise that would force employers to cover employees’ injuries regardless of cause, in exchange for this being the employees’ sole remedy.

- Workers’ compensation laws are inclusive or exclusive, compulsory or elective.

- Covered injuries must arise out of and in the course of employment or be occupational diseases.

-

Benefits provided under workers’ compensation are medical, income replacement, survivors’ benefits, and rehabilitation.

- Medical—unlimited as of the date of occurrence

- Income replacement—usually at 66⅔ percent of the average weekly wage, subject to state maximum, lifetime maximum, and degree and length of disability

- Survivor’s benefits—income benefits and burial allowances

- Rehabilitation—physical, vocational, and psychological care necessary to restore (to the greatest extent possible) injured workers to their former economic and social situation

Discussion Questions

- Explain the former common law defenses employers utilized to avoid liability for employees’ on-the-job injuries.

- What are the arguments for and against allowing employers to opt out of the workers’ compensation systems in Texas and New Jersey?

- Given the rapid increases in workers’ compensation costs, would you argue that other states should return to offering an opt-out provision? (Note: In the early days of workers’ compensation laws in the United States, opt-out provisions were common because of concern about whether making workers’ compensation mandatory was constitutional—now, not an issue.)

- A worker is entitled to workers’ compensation benefits when disability “arises out of and in the course of employment.” A pregnant employee applies for medical and income benefits, alleging that her condition arose out of and in the course of the company’s annual Christmas party. Is she entitled to benefits? Why or why not?

16.2 How Benefits Are Provided

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on the following ways that workers’ compensation benefits are distributed:

- Private insurance

- Residual markets

- State funds

- Self-insurance

- Second-injury funds

Workers’ compensation laws hold the employer responsible for providing benefits to injured employees. Employees do not contribute directly to this cost. In most states, employers may insure with a private insurance company or qualify as self-insurers. In some states, state funds act as insurers. Following is a discussion of coverage through insurance programs and through the residual markets (part of insurance programs for difficult-to-insure employers), self-insurance, and state funds.

Workers’ Compensation Insurance

Employers’ risks can be transferred to an insurer by purchasing a workers’ compensation and employers’ liability policy.

Coverage

The workers’ compensation and employers’ liability policy has three parts. Under part I, Workers’ Compensation, the insurer agrees

to pay promptly when due all compensation and other benefits required of the insured by the workers’ compensation law.

The policy defines “workers’ compensation law” as the law of any state designated in the declarations and specifically includes any occupational disease law of that state. The workers’ compensation portion of the policy is directly for the benefit of employees covered by the law. The insurer assumes the obligations of the insured (that is, the employer) under the law and is bound by the terms of the law as well as the actions of the workers’ compensation commission or other governmental body having jurisdiction. Any changes in the workers’ compensation law are automatically covered by the policy.

Four limitations, or “exclusions,” apply to part 1. These limitations include any payments in excess of the benefits regularly required by workers’ compensation statutes due to (1) serious and willful misconduct by the insured; (2) the knowing employment of a person in violation of the law; (3) failure to comply with health or safety laws or regulations; or (4) the discharge, coercion, or other discrimination against employees in violation of the workers’ compensation law. In addition, the policy refers only to state laws and that of the District of Columbia; thus, coverage under any of the federal programs requires special provisions.

Part 2 of the workers’ compensation policy, Employers’ LiabilityPortion of a worker’s compensation policy that protects against potential liabilities not within the scope of the workers’ compensation law, yet arising out of employee injuries., protects against potential liabilities not within the scope of the workers’ compensation law, yet arising out of employee injuries. The insurer agrees to pay damages for which the employer becomes legally obligated because of

bodily injury by accident or disease, including death at any time resulting there from … by any employee of the insured arising out of and in the course of his employment by the insured either in operations in a state designated in … the declarations or in operations necessary or incidental thereto.

Examples of liabilities covered under part 2 are those to employees excluded from the law, such as domestic and farm laborers. Part 2 might also be applicable if the injury is not considered work-related, even if it occurs on the job.

Part 3 of the workers’ compensation policy provides Other States Insurance. Previously, this protection was available by endorsement. Part 1 applies only if the state imposing responsibility is listed in the declarations. To account for the case of an employee injured while working out of state who may be covered by that state’s compensation law, the Other States InsurancePortion of a worker’s compensation policy that allows the insured to list states (perhaps all) where the employees may have potential exposure. part of the workers’ compensation policy allows the insured to list states (perhaps all) where the employees may have potential exposure. Coverage is extended to these named locales.

Cost

Based on Payroll

The premium for workers’ compensation insurance typically is based on the payroll paid by the employer. A charge is made for each $100 of payroll for each classification of employee. This rate varies with the degree of hazard of the occupation.Rates are made for each state and depend on the experience under the law in that state. Thus, the rate for the same occupational classification may differ from state to state. Large employers can elect to have experience rating, which takes a company’s prior losses into account in determining its current rates.

Factors Affecting Rate

The rate for workers’ compensation insurance is influenced not only by the degree of hazard of the occupational classification but also by the nature of the law and its administration and, of course, by prior losses. If the benefits of the law are high, rates will tend to be high. If they are low, rates will tend to be low. Moreover, given any law, no matter its benefits level, its administration will affect premium rates. If those who administer the law are conservative in their evaluation of borderline cases, premium rates will be lower than in instances where administrators are less circumspect in parceling out employers’ and insurers’ money. Most laws provide that either the claimant or the insurer may appeal a decision of the administrative board in court on questions of law, but if both the board and the courts are inclined toward generosity, the effect is to increase workers’ compensation costs.

Workers’ compensation may be a significant expense for the employer. Given any particular law and its administration, costs for the firm are influenced by the frequency and severity of injuries suffered by workers covered. The more injuries, the more workers will be receiving benefits. The more severe such injuries are, the longer such benefits must be paid. It is not unusual to find firms in hazardous industries having workers’ compensation costs running from 10 to 30 percent of payroll. This can be a significant component of labor costs. Whatever their size, however, these costs are only part of the total cost of occupational injury and disease. The premium paid is the firm’s direct cost, but indirect costs of industrial accidents, such as lost time, spoiled materials, and impairment of worker morale, can be just as significant. These costs can be reduced by loss prevention and reduction, and by self-insuring the risk.

Loss Prevention and Reduction

Most industrial accidents are caused by a combination of physical hazard and faulty behavior. Once an accident begins to occur, the ultimate severity is largely a matter of chance. Total loss costs are a function of accident frequency and severity as explained in prior chapters. Frequency is a better indicator of safety performance than severity because chance plays a greater part in determining the seriousness of an injury than it does in determining frequency.

Accident Prevention

The first consideration is to reduce frequency by preventing accidents. Safety must be part of your thinking, along with planning and supervising. Any safety program should be designed to accomplish two goals: (1) reduce hazards to a minimum, and (2) develop safe behavior in every employee. A safety engineer from the workers’ compensation insurer (or a consultant for the self-insured employer) can give expert advice and help the program. He or she can identify hazards so they can be corrected. This involves plant inspection, job safety analysis, and accident investigation.

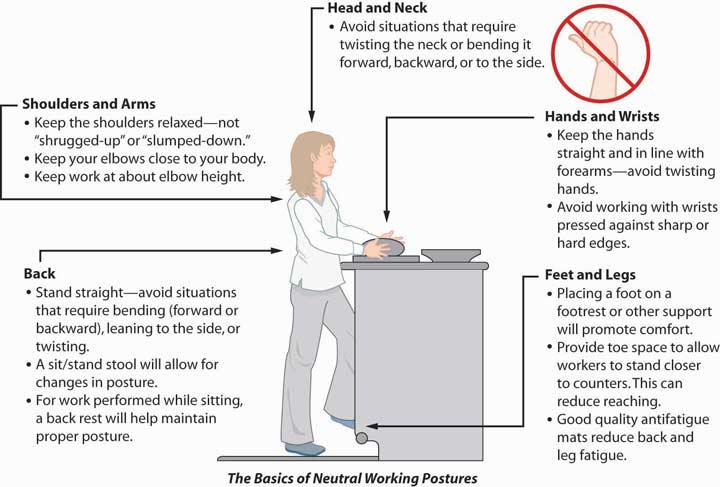

The safety engineer can inspect the plant to observe housekeeping, machinery guarding, maintenance, and safety equipment. He or she can help the employer organize and implement a safety training program to develop employee awareness and safe practices. He or she can analyze job safety to determine safe work methods and can set job standards that promote safety. The insurer usually provides employers with accident report forms and instructions on accident investigation. This is essential because every accident demonstrates a hazardous condition or an unsafe practice, or both. The causes of accidents must be discovered so that the information can assist in future prevention efforts. Inspections, job safety analysis, and accident investigations that lead consistently to corrective action are the foundations of accident prevention. The box “Should Ergonomic Standards Be Mandatory?” discusses the issues of job safety in the area of posture and position in the workplace.

Loss Reduction

Accident frequency cannot be reduced to zero because not all losses can be prevented. After an employee has suffered an injury, however, action may reduce the loss. First, immediate medical attention may save a life. Moreover, recovery will be expedited. This is why many large plants have their own medical staff. It is also why an employer should provide first-aid instruction for its employees. Second, the insurer along with the employer should manage the care of the injured worker, including referrals to low-cost, high-quality medical providers. Third, injured workers should take advantage of rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is not always successful, but experience has shown that remarkable progress is possible, especially if it is started soon enough after an injury. The effort is worthwhile from both the economic and humanitarian points of view. All of society benefits from such effort.

Residual Market

Various residual market mechanisms, such as assigned risk pools and reinsurance facilities, allow employers that are considered uninsurable access to workers’ compensation insurance. This is similar to the structure discussed earlier for automobile insurance. Usually employers with large losses, as depicted by high experience ratings, are considered high risk. These employers encounter difficulty in finding workers’ compensation coverage. The way to obtain coverage is through the residual or involuntary market (a market where insurers are required to provide coverage on an involuntary basis). Insurers are required to participate, and insureds are assigned to an insurer in various ways.

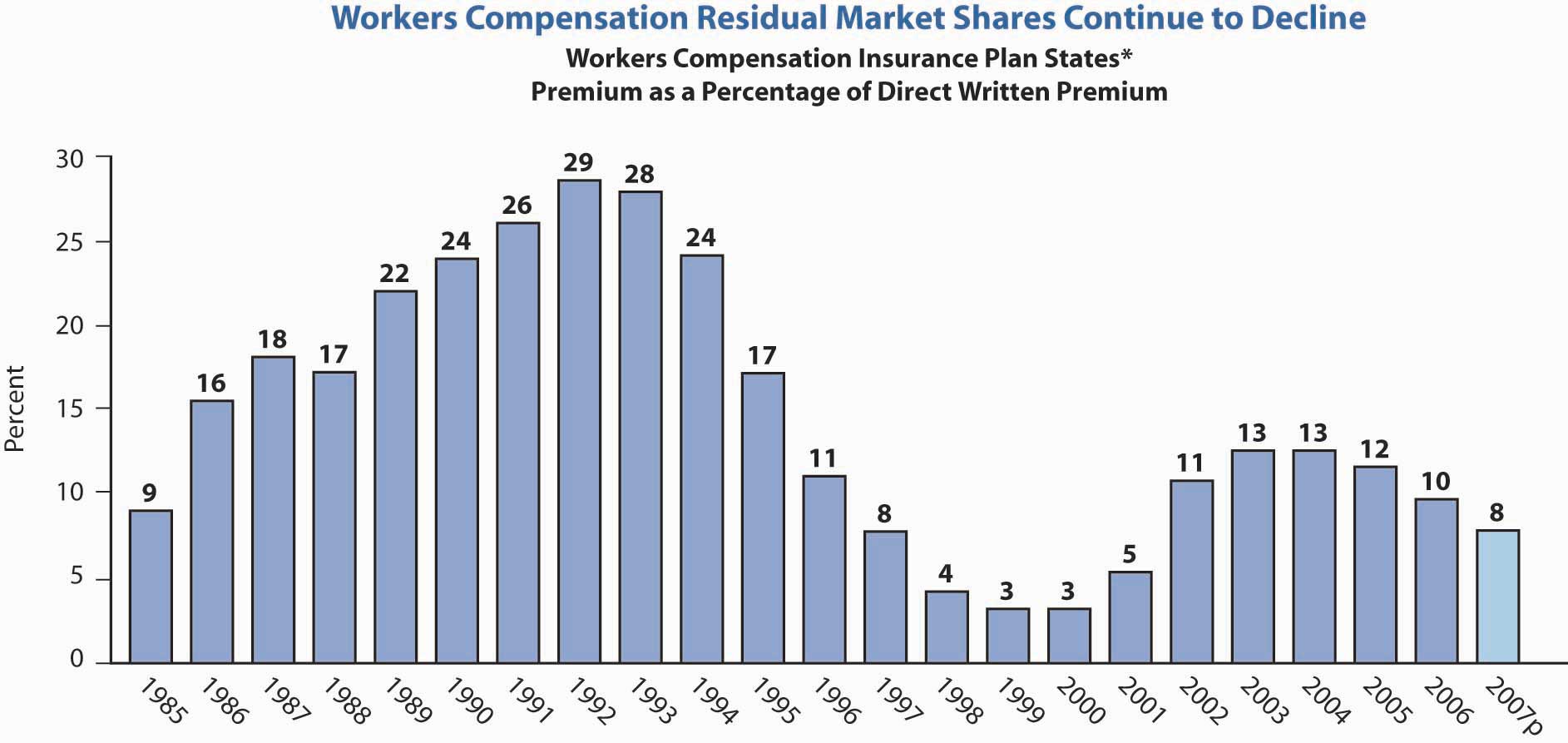

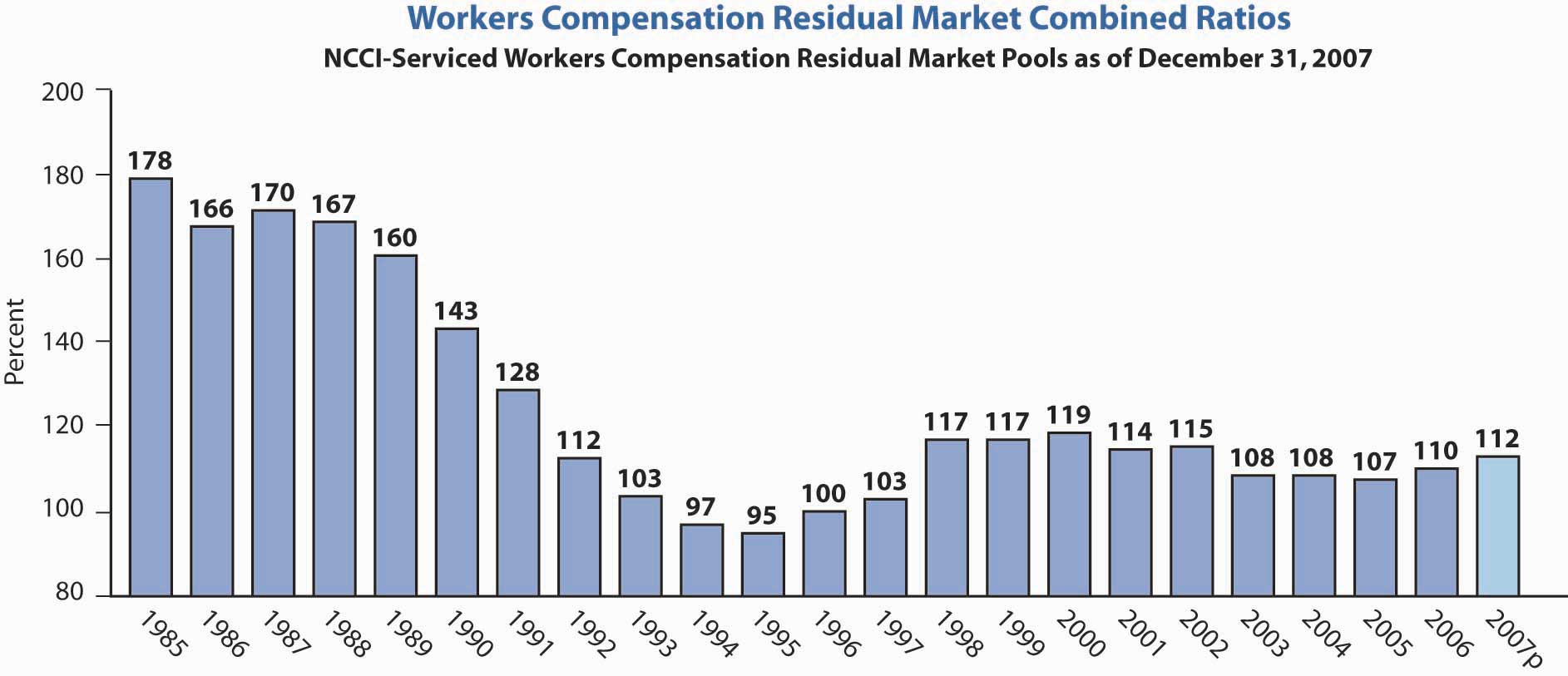

As reported in the NCCI “State of the Line” report, Figure 16.4 "Residual Market Premiums as of December 31, 2007" provides the workers’ compensation residual market premiums from 1985 to 2006; Figure 16.5 "Residual Market Combined Ratio as of December 31, 2007" provides the residual market combined ratio for the same period.

Eighteen jurisdictions have state-operated workers’ compensation fundsState government agencies responsible for collecting workers’ compensation founds and distributing benefits. in which the state government is responsible for collecting workers’ compensation founds and distributing benefits. In six of these, the state fund is exclusive; that is, employers are not permitted to buy compensation insurance from a private insurance company but must insure with the state fund or self-insure.Three of the six permit self-insurance exclusive funds are called monopolistic state funds. Where the state fund is competitive (that is, optional), employers may choose to self-insure or to insure through either the state fund or a private insurer.

Employer’s Risk

Industrial accidents create two possible losses for employers. First, employers are responsible to employees covered by the workers’ compensation law for the benefits required by law. Second, they may become liable for injuries to employees not covered by the law.For example, many workers’ compensation laws exclude workers hired for temporary jobs, known as casual workers. Injured employees who are classified as casual workers are not entitled to benefits under the law but may recover damages from the employer if they can prove that their injuries were caused by the employer’s negligence. The employer’s liability risk with regard to excluded employees is the same as it would be if there was no workers’ compensation law. The risks associated with these exposures cannot be avoided without suspending operations—hardly a practical alternative.

Where permitted, self-insurance of this exposure is common. Self-insurance is desirable, in part because of the predictability afforded by legislated benefits. In addition, employers can buy coverage (called excess loss insurance) for very large losses similar to the commercial umbrella liability policy discussed in Chapter 15 "Multirisk Management Contracts: Business" .

Figure 16.4 Residual Market Premiums as of December 31, 2007

* NCCI Plan states plus DE, IN, MA, MI, NJ, NC

Source: Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), Inc. Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, Accessed March 28, 2009, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf. © 2008 NCCI Holdings, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 16.5 Residual Market Combined Ratio as of December 31, 2007

Source: Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), Inc. Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, Accessed March 28, 2009, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf. © 2008 NCCI Holdings, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

Self-Insurance

Most state workers’ compensation laws permit an employer to retain the workers’ compensation risk if it can be proven that the employer is financially able to pay claims. Some states permit the risk to be retained only by employers who furnish a bond guaranteeing payment of benefits.

The major question for the self-insurance of the workers’ compensation risk is whether the firm has a large enough number of exposure units (employees) that its losses are reasonably stable and can be predicted with some accuracy. Clearly, an employer with ten employees cannot make an accurate prediction of workers’ compensation benefit costs for next year. Such costs may be zero one year and several thousand dollars another year. On the other hand, as the number of employees of the firm increases, workers’ compensation losses become more stable and predictable. Just how stable losses must be in order for self-insurance to be feasible depends on the employer’s ability and willingness to pay for losses that exceed expectations. The employer’s ability to pay for loss is a second important factor considered by regulators in determining whether or not to permit self-insurance. Captives are also used by many employers for this coverage. Of course, all types of self-insurance require the use of stop-loss coverage through reinsurance. The reinsurance is best for use with captives, as explained in Chapter 6 "The Insurance Solution and Institutions". Smaller employers can join together with others, usually from the same industry, and create a group self-insurance program. Under these programs, each employer is responsible for paying the losses of the group when necessary—such as in the case of a member’s insolvency. The employer’s risk is not transferred; only the payment of losses is shared through the pooling mechanism discussed in Chapter 6 "The Insurance Solution and Institutions". Group self-insurance members buy stop-loss coverage and are required to obtain regulatory approval for their existence.

Insurance or Self-Insurance?

Is your firm large enough to self-insure, and if it is, can you save money by doing so? Unless you have at least several hundred employees and your workers’ compensation losses have a low correlation with other types of retained exposures, self-insurance is not feasible. The low correlation implies diversification of the retained risk exposures. Unless self-insurance will save money, it is not worthwhile. Most employers who decide to self-insure use third-party administrators to administer the claims or contract with an insurer to provide administrative services only.

What are the possible sources for saving money? Ask yourself the following questions about your present arrangement:

- Does your insurer pay benefits too liberally?

- Does it bear the risk of excessive losses?

- Does it bear the risk of employers’ liability?

- Does it administer the program?

- How large is the premium tax paid by the insurer?

- How large is the insurer’s profit on your business?

- What is your share of losses in the assigned risk plan that the insurer pays into?

- Can the third-party administrator be a good buffer in disputes with angry employees?

As a self-insured firm, you will still provide the benefits specified by the workers’ compensation law(s) in the state(s) where you operate. Therefore, self-insuring reduces benefits only if you or your outside self-insurance administrator will settle claims more efficiently than your insurer.

Unless your firm is very large, you probably would decide to buy stop-loss insurance for excessive losses, and you would buy insurance for your employer’s liability (part B of a workers’ compensation insurance policy). Would you administer the self-insured program? Most likely, you would hire an outside administrator. In either case, the administrative expenses might be similar to those of your insurer. As a self-insurer, you would save the typical premium tax of between 2 and 3 percent that your insurer is required to pay to the state(s) where you do business. Profits are difficult to calculate because the insurer’s investment income must be factored in along with premiums, benefit payments, expenses, and your own opportunity cost of funds. If you do not pay premiums ahead, you can use the cash flow for other activities until they are used to pay for losses. While the workers’ compensation line of business produces losses in some years and profits in others, over a period of several years, you would expect the insurer to make a profit on your business. You could retain this profit by self-insuring.

Firms that do not qualify for insurance based on normal underwriting guidelines and premiums can buy insurance through an assigned risk plan, that is, the residual market. Because of inadequate rates and other problems, large operating losses are often realized in the residual market. These losses become an additional cost to be borne by insurers and passed on to insureds in the form of higher premiums. Assigned risk pool losses are allocated to insurers on the basis of their share of the voluntary (nonassigned risk) market by state and year. These losses can be 15 to 30 percent or more of premiums for employers insured in the voluntary market. This burden can be avoided by self-insuring. Many firms have self-insured for this reason, resulting in a smaller base over which to spread the residual market burden.

If your firm is large enough to self-insure, your workers’ compensation premium is experience ratedWhen a group’s own claims experience affects the cost of coverage for group insurance.. What you pay this year is influenced by your loss experience during the past three years. The extent to which your rate goes up or down to reflect bad or good experience depends on the credibility assigned by the insurer. This statistical credibility is primarily determined by the size of your firm. The larger your firm, the more your experience influences the rate you pay during succeeding years.

If an employer wants the current year’s experience rating to influence what it pays for workers’ compensation coverage this year, you can insure on a retrospective planWorker’s compensation policy that involves payment of a premium between a minimum and a maximum, depending on the insured’s loss experience.. It involves payment of a premium between a minimum and a maximum, depending on your loss experience. Regardless of how favorable your experience is, you must pay at least the minimum premium. On the other hand, regardless of how bad your experience is, you pay no more than the maximum. Between the minimum and the maximum, your actual cost for the year depends on your experience that year.

Several plans with various minimum and maximum premium stipulations are available. If you are conservative with respect to risk, you will prefer a low minimum and a low maximum, but that is the most expensive. Low minimum and high maximum is cheaper, but this puts most of the burden of your experience on you. If you have an effective loss prevention and reduction program, you may choose the high maximum and save money on your workers’ compensation insurance.

In choosing between insurance and self-insurance, you should consider the experience rating plans provided by insurers, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of self-insurance. The process of making this comparison will undoubtedly be worthwhile.

State Funds

A third method of ensuring benefit payments to injured workers is the state fund. State funds are similar to private insurers except that they are operated by an agency of the state government, and most are concerned only with benefit payments under the workers’ compensation law and do not assume the employers’ liability risk. This usually must be insured privately. The employer pays a premium (or tax) to the state fund and the fund, in turn, provides the benefits to which injured employees are entitled. Some state funds decrease rates for certain employers or classes of employers if their experience warrants it.

Cost comparisons between commercial insurers and state funds are difficult because the state fund may be subsidized. In some states, the fund may exist primarily to provide insurance to employers in high-risk industries—for example, coal mining—that are not acceptable to commercial insurers. In any case, employers who have access to a state fund should consider it part of the market and compare its rates with those of private insurers.

Second-Injury Funds

Nature and Purpose

If two employees with the same income each lost one eye in an industrial accident, the cost in workers’ compensation benefits for each would be equal. If one of these employees had previously lost an eye, however, the cost of benefits for him or her would be much greater than for the other worker (probably more than double the cost). Obviously, the loss of both eyes is a much greater handicap than the loss of one. To encourage employment in these situations, second-injury funds are part of most workers’ compensation laws. When an employee suffers a second injury, the employee is compensated for the disability resulting from the combined injuries; the insurer (or employer) who pays the benefit is then reimbursed by a second-injury fundFund that reimburses an insurer (or employer) that pays a workman’s compensation benefit to an employee who suffers more than one job-related injury. for the amount by which the combined disability benefits exceed the benefit that would have been paid only for the last injury.

Financing

Second-injury funds are financed in a variety of ways. Some receive appropriations from the state. Others receive money from a charge made against an employer or an insurer when a worker who has been killed on the job does not leave any dependents. Some states finance the fund by annual assessments on insurers and self-insurers. These assessments can be burdensome.

Key Takeaways

In this section you studied the ways workers’ compensation benefits are provided through insurance programs, residual markets, self-insurance, and state funds:

- Employers’ risks can be transferred to a workers’ compensation and employers’ liability policy, which pays for the benefits injured workers are entitled to under workers’ compensation law and for expenses incurred as a result of liability on the part of the employer.

- Workers’ compensation insurance premiums are based on payroll and experience (which is in turn influenced by loss prevention and reduction efforts).

- Employers considered uninsurable can obtain workers’ compensation insurance through the residual market, made of assigned risk pools and reinsurance facilities.

- Some jurisdictions have state-operated workers’ compensation funds as either the only source of workers’ compensation coverage or as an alternative to the private market.

- Large employers with sufficient financial resources may be able to self-insure and thus pay for workers’ compensation.

- Second-injury funds are set up to reimburse employers for payment to injured workers who suffer subsequent injuries that more than double the cost of providing them with compensation.

Discussion Questions

- How are workers’ compensation rates influenced?

- Under what circumstances should an employer retain workers’ compensation risk?

- How does a retrospective premium plan work?

- What is the purpose of second-injury funds?

16.3 Workers’ Compensation Issues

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on several issues that workers’ compensation insurers must contend with, including the following:

- Cost drivers and reform

- Erosion of exclusive remedy

- Scope of coverage

As noted by the National Council of Compensation Insurance (NCCI), despite the improved results of the workers’ compensation line, the following are challenging issues faced by the industry:

- Catastrophes such as terrorism

- Cost drivers and reform

- Capacity

- Adequate reserves

- Privacy

- Erosion of exclusive remedy and scope of coverage

- Mental health claims

- Black lung

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

- Ergonomics

Coverage for terrorism is a major issue for workers’ compensation. The problem has been somewhat alleviated by the relaunch of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) of 2002 as the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (TRIPRA), which provides protection until December 31, 2014. It is not a permanent solution, so the stakeholders are working on permanent solutions, including overall catastrophe pools.

As noted earlier, medical inflation, in addition to increased benefits through reforms in the states and attorney fees, have cost the system a substantial amount of extra expenses and caused escalation in the combined ratio for the workers’ compensation line. All medical care costs have, for decades, grown much faster than the overall consumer price index (CPI). Workers’ compensation medical care costs are of special concern. The high reimbursement rate (100 percent of allowable charges) by workers’ compensation relative to lower rates (generally 80 to 90 percent) in nonoccupational medical plans creates a preference for workers’ compensation among employees and medical care providers who influence some decisions about whether or not a claim is deemed work-related. The managed care option mentioned above is used, but because medical inflation is so high, the system cannot resolve the issue on its own.

Attorney involvement varies substantially among the states. It is encouraged by factors such as the following:

- The complexity of the law

- Weak early communication to injured workers

- Advertisements by attorneys

- Failure to begin claim payments soon after the start of disability

- Employee distrust of some employers and insurers

- Employee concern that some employers will not rehire injured workers

- The subjective nature of benefit determination (e.g., encouraging both parties to produce conflicting medical evidence concerning the degree of impairment)

The solution may be a system that settles claims equitably and efficiently through promoting agreement and the employee’s timely return to work. Reforms in states such as California, Florida, Tennessee, and Wisconsin are examples of positive effects and cost controls. Wisconsin’s system is an example characterized by prompt delivery of benefits, low transaction costs, and clear communication between employers and employees.

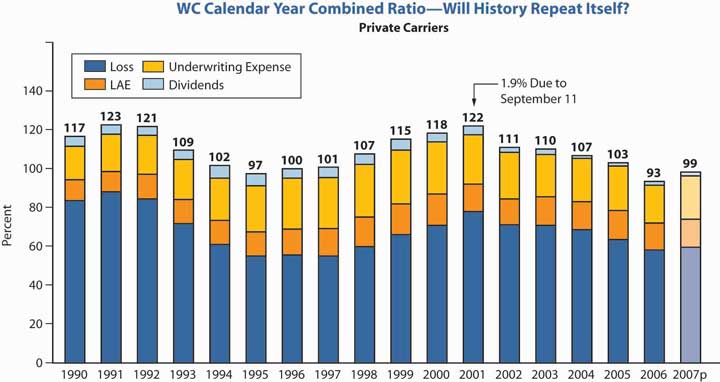

The workers’ compensation combined ratio per calendar year since 1990 is shown in Figure 16.6 "Workers’ Compensation Combined Ratios". The combined ratio has declined since its peak of 122 in 2001.

Figure 16.6 Workers’ Compensation Combined Ratios

Source: Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), Inc. Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, accessed March 28, 2009, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf. © 2008 NCCI Holdings, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

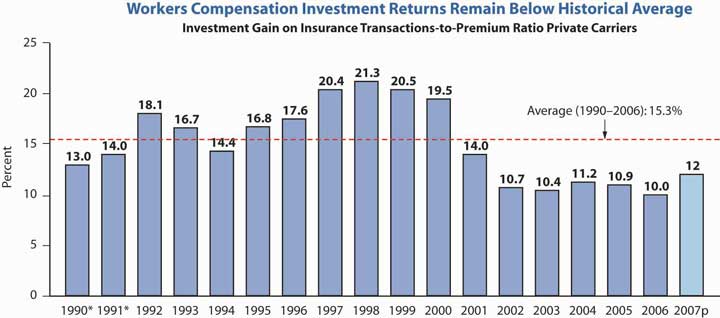

As for the whole property/casualty industry, investment income results kept declining. The low interest rates took a toll on this long-tail line, requiring underwriting profits in order to provide returns to investors. The poor investment results are shown in Figure 16.7 "Workers’ Compensation Ratios of Investment Gain and Other Income to Premium".

Figure 16.7 Workers’ Compensation Ratios of Investment Gain and Other Income to Premium

* Adjusted to include realized capital gains to be consistent with 1992 and after.

Investment gain on insurance transactions includes other income.

Source: Dennis C. Mealy, FCAS, MAAA, National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), Inc. Chief Actuary, “State of the Line” Annul Issues Symposium (AIS), May 8, 2008, accessed March 28, 2009, https://www.ncci.com/documents/AIS-2008-SOL-Complete.pdf. © 2008 NCCI Holdings, Inc. Reproduced with permission.

The next issue, privacy, has been discussed in prior chapters. This is an issue engulfing the whole industry and is relevant to the workers’ compensation line because of the medical and health components of this coverage. How to protect individuals’ health information from being identified and transmitted is the industry’s concern.

Employers, of course, benefit from having their liabilities limited to what is stipulated in workers’ compensation laws. When the benefits received by workers are a close approximation of what would be received under common law, employees receive a clear advantage as well from the law. Today, however, there is a perception that workers’ compensation provides inadequate compensation for many injuries. With high awards for punitive and general damages (neither available in workers’ compensation) in tort claims, workers often perceive the exclusivity of compensation laws as inequitable.

As a result, workers attempt to circumvent the exclusivity rule. One method is to claim that the employer acts in a dual capacity, permitting the employee an action against the employer in the second relationship as well as a workers’ compensation claim. For example, an employee injured while using a product manufactured by another division of the company might seek a products liability claim against the employer. Dual capacity has received limited acceptance. Consider the case of an employee of Firestone tires who uses the employer’s commercial auto with Firestone tires to make deliveries. If a tire exploded, the employee has a workers’ compensation claim as well as a case against the manufacturer of the tire—his own employer.

A second means of circumventing the exclusivity of workers’ compensation is to claim that the employer intentionally caused the injury. Frequently, this claim is made with respect to exposure to toxic substances. Employees claim that employers knew of the danger but encouraged employees to work in the hazardous environment anyway. This argument, too, has received limited acceptance, and litigation of these cases is costly. Further, their mere existence likely indicates at least a perception of faults in the workers’ compensation system.

A third circumvention of the exclusivity of workers’ compensation is the third-party over action. It begins with an employee’s claim against a third party (not the employer). For example, the employee may sue a machine manufacturer for products liability if the employee is injured while using the manufacturer’s machine. In turn, the third party (the manufacturer in our example) brings an action against the employer for contribution or indemnification. The action against the employer might be based on the theory that the employer contributed to the loss by failing to supervise its employees properly. The end result is an erosion of the exclusive remedy rule—as if the employee had sued the employer directly.

Another current issue in workers’ compensation is the broadening of the scope of covered claims. The original intent of workers’ compensation laws was to cover only work-related physical injuries. Later, coverage was extended to occupational illnesses that often are not clearly work-related. Claims for stress and cases involving mental health claims, especially after September 11, are on the increase.