This is “Types of Risks—Risk Exposures”, section 1.4 from the book Enterprise and Individual Risk Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.4 Types of Risks—Risk Exposures

Learning Objectives

- In this section, you will learn what a risk professional means by exposure.

- You will also learn several different ways to split risk exposures according to the risk types involved (pure versus speculative, systemic versus idiosyncratic, diversifiable versus nondiversifiable).

- You will learn how enterprise-wide risk approaches combine risk categories.

Most risk professionals define risk in terms of an expected deviation of an occurrence from what they expect—also known as anticipated variabilityAn expected deviation of an occurrence from what one expects.. In common English language, many people continue to use the word “risk” as a noun to describe the enterprise, property, person, or activity that will be exposed to losses. In contrast, most insurance industry contracts and education and training materials use the term exposureTerm used to describe the enterprise, property, person, or activity facing a potential loss. to describe the enterprise, property, person, or activity facing a potential loss. So a house built on the coast near Galveston, Texas, is called an “exposure unit” for the potentiality of loss due to a hurricane. Throughout this text, we will use the terms “exposure” and “risk” to note those units that are exposed to losses.

Pure versus Speculative Risk Exposures

Some people say that Eskimos have a dozen or so words to name or describe snow. Likewise, professional people who study risk use several words to designate what others intuitively and popularly know as “risk.” Professionals note several different ideas for risk, depending on the particular aspect of the “consequences of uncertainty” that they wish to consider. Using different terminology to describe different aspects of risk allows risk professionals to reduce any confusion that might arise as they discuss risks.

As we noted in Table 1.2 "Examples of Pure versus Speculative Risk Exposures", risk professionals often differentiate between pure riskRisk that features some chance of loss and no chance of gain. that features some chance of loss and no chance of gain (e.g., fire risk, flood risk, etc.) and those they refer to as speculative risk. Speculative risksRisk that features a chance to either gain or lose. feature a chance to either gain or lose (including investment risk, reputational risk, strategic risk, etc.). This distinction fits well into Figure 1.3 "Roles (Objectives) Underlying the Definition of Risk". The right-hand side focuses on speculative risk. The left-hand side represents pure risk. Risk professionals find this distinction useful to differentiate between types of risk.

Some risks can be transferred to a third party—like an insurance company. These third parties can provide a useful “risk management solution.” Some situations, on the other hand, require risk transfers that use capital markets, known as hedging or securitizations. HedgingActivities that are taken to reduce or eliminate risks. refers to activities that are taken to reduce or eliminate risks. SecuritizationPackaging and transferring the insurance risks to the capital markets through the issuance of a financial security. is the packaging and transferring of insurance risks to the capital markets through the issuance of a financial security. We explain such risk retention in Chapter 4 "Evolving Risk Management: Fundamental Tools" and Chapter 5 "The Evolution of Risk Management: Enterprise Risk Management". Risk retentionWhen a firm retains its risk, self-insuring against adverse contingencies out of its own cash flows. is when a firm retains its risk. In essence it is self-insuring against adverse contingencies out of its own cash flows. For example, firms might prefer to capture up-side return potential at the same time that they mitigate while mitigating the downside loss potential.

In the business environment, when evaluating the expected financial returns from the introduction of a new product (which represents speculative risk), other issues concerning product liability must be considered. Product liabilitySituation in which a manufacturer may be liable for harm caused by use of its product, even if the manufacturer was responsible in producing it. refers to the possibility that a manufacturer may be liable for harm caused by use of its product, even if the manufacturer was reasonable in producing it.

Table 1.2 "Examples of Pure versus Speculative Risk Exposures" provides examples of the pure versus speculative risks dichotomy as a way to cross classify risks. The examples provided in Table 1.2 "Examples of Pure versus Speculative Risk Exposures" are not always a perfect fit into the pure versus speculative risk dichotomy since each exposure might be regarded in alternative ways. Operational risks, for example, can be regarded as operations that can cause only loss or operations that can provide also gain. However, if it is more specifically defined, the risks can be more clearly categorized.

The simultaneous consideration of pure and speculative risks within the objectives continuum of Figure 1.3 "Roles (Objectives) Underlying the Definition of Risk" is an approach to managing risk, which is known as enterprise risk management (ERM)The simultaneous consideration of all risks and the management of risks in an enterprise-wide (and risk-wide) context.. ERM is one of today’s key risk management approaches. It considers all risks simultaneously and manages risk in a holistic or enterprise-wide (and risk-wide) context. ERM was listed by the Harvard Business Review as one of the key breakthrough areas in their 2004 evaluation of strategic management approaches by top management.L. Buchanan, “Breakthrough Ideas for 2004,” Harvard Business Review 2 (2004): 13–16. In today’s environment, identifying, evaluating, and mitigating all risks confronted by the entity is a key focus. Firms that are evaluated by credit rating organizations such as Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s are required to show their activities in the areas of enterprise risk management. As you will see in later chapters, the risk manager in businesses is no longer buried in the tranches of the enterprise. Risk managers are part of the executive team and are essential to achieving the main objectives of the enterprise. A picture of the enterprise risk map of life insurers is shown later in Figure 1.5 "A Photo of Galveston Island after Hurricane Ike".

Table 1.2 Examples of Pure versus Speculative Risk Exposures

| Pure Risk—Loss or No Loss Only | Speculative Risk—Possible Gains or Losses |

|---|---|

| Physical damage risk to property (at the enterprise level) such as caused by fire, flood, weather damage | Market risks: interest risk, foreign exchange risk, stock market risk |

| Liability risk exposure (such as products liability, premise liability, employment practice liability) | Reputational risk |

| Innovational or technical obsolescence risk | Brand risk |

| Operational risk: mistakes in process or procedure that cause losses | Credit risk (at the individual enterprise level) |

| Mortality and morbidity risk at the individual level | Product success risk |

| Intellectual property violation risks | Public relation risk |

| Environmental risks: water, air, hazardous-chemical, and other pollution; depletion of resources; irreversible destruction of food chains | Population changes |

| Natural disaster damage: floods, earthquakes, windstorms | Market for the product risk |

| Man-made destructive risks: nuclear risks, wars, unemployment, population changes, political risks | Regulatory change risk |

| Mortality and morbidity risk at the societal and global level (as in pandemics, social security program exposure, nationalize health care systems, etc.) | Political risk |

| Accounting risk | |

| Longevity risk at the societal level | |

| Genetic testing and genetic engineering risk | |

| Investment risk | |

| Research and development risk |

Within the class of pure risk exposures, it is common to further explore risks by use of the dichotomy of personal property versus liability exposure risk.

Personal Loss Exposures—Personal Pure Risk

Because the financial consequences of all risk exposures are ultimately borne by people (as individuals, stakeholders in corporations, or as taxpayers), it could be said that all exposures are personal. Some risks, however, have a more direct impact on people’s individual lives. Exposure to premature death, sickness, disability, unemployment, and dependent old age are examples of personal loss exposures when considered at the individual/personal level. An organization may also experience loss from these events when such events affect employees. For example, social support programs and employer-sponsored health or pension plan costs can be affected by natural or man-made changes. The categorization is often a matter of perspective. These events may be catastrophic or accidental.

Property Loss Exposures—Property Pure Risk

Property owners face the possibility of both direct and indirect (consequential) losses. If a car is damaged in a collision, the direct loss is the cost of repairs. If a firm experiences a fire in the warehouse, the direct cost is the cost of rebuilding and replacing inventory. Consequential or indirect lossesA nonphysical loss such as loss of business. are nonphysical losses such as loss of business. For example, a firm losing its clients because of street closure would be a consequential loss. Such losses include the time and effort required to arrange for repairs, the loss of use of the car or warehouse while repairs are being made, and the additional cost of replacement facilities or lost productivity. Property loss exposuresLosses associated with both real property such as buildings and personal property such as automobiles and the contents of a building. are associated with both real property such as buildings and personal property such as automobiles and the contents of a building. A property is exposed to losses because of accidents or catastrophes such as floods or hurricanes.

Liability Loss Exposures—Liability Pure Risk

The legal system is designed to mitigate risks and is not intended to create new risks. However, it has the power of transferring the risk from your shoulders to mine. Under most legal systems, a party can be held responsible for the financial consequences of causing damage to others. One is exposed to the possibility of liability lossLoss caused by a third party who is considered at fault. (loss caused by a third party who is considered at fault) by having to defend against a lawsuit when he or she has in some way hurt other people. The responsible party may become legally obligated to pay for injury to persons or damage to property. Liability risk may occur because of catastrophic loss exposure or because of accidental loss exposure. Product liability is an illustrative example: a firm is responsible for compensating persons injured by supplying a defective product, which causes damage to an individual or another firm.

Catastrophic Loss Exposure and Fundamental or Systemic Pure Risk

Catastrophic risk is a concentration of strong, positively correlated risk exposures, such as many homes in the same location. A loss that is catastrophic and includes a large number of exposures in a single location is considered a nonaccidental risk. All homes in the path will be damaged or destroyed when a flood occurs. As such the flood impacts a large number of exposures, and as such, all these exposures are subject to what is called a fundamental riskRisks that are pervasive to and affect the whole economy, as opposed to accidental risk for an individual.. Generally these types of risks are too pervasive to be undertaken by insurers and affect the whole economy as opposed to accidental risk for an individual. Too many people or properties may be hurt or damaged in one location at once (and the insurer needs to worry about its own solvency). Hurricanes in Florida and the southern and eastern shores of the United States, floods in the Midwestern states, earthquakes in the western states, and terrorism attacks are the types of loss exposures that are associated with fundamental risk. Fundamental risks are generally systemic and nondiversifiable.

Figure 1.5 A Photo of Galveston Island after Hurricane Ike

Accidental Loss Exposure and Particular Pure Risk

Many pure risks arise due to accidental causes of loss, not due to man-made or intentional ones (such as making a bad investment). As opposed to fundamental losses, noncatastrophic accidental losses, such as those caused by fires, are considered particular risks. Often, when the potential losses are reasonably bounded, a risk-transfer mechanism, such as insurance, can be used to handle the financial consequences.

In summary, exposures are units that are exposed to possible losses. They can be people, businesses, properties, and nations that are at risk of experiencing losses. The term “exposures” is used to include all units subject to some potential loss.

Another possible categorization of exposures is as follows:

- Risks of nature

- Risks related to human nature (theft, burglary, embezzlement, fraud)

- Man-made risks

- Risks associated with data and knowledge

- Risks associated with the legal system (liability)—it does not create the risks but it may shift them to your arena

- Risks related to large systems: governments, armies, large business organizations, political groups

- Intellectual property

Pure and speculative risks are not the only way one might dichotomize risks. Another breakdown is between catastrophic risks, such as flood and hurricanes, as opposed to accidental losses such as those caused by accidents such as fires. Another differentiation is by systemic or nondiversifiable risks, as opposed to idiosyncratic or diversifiable risks; this is explained below.

Diversifiable and Nondiversifiable Risks

As noted above, another important dichotomy risk professionals use is between diversifiable and nondiversifiable risk. Diversifiable risksRisks whose adverse consequences can be mitigated simply by having a well-diversified portfolio of risk exposures. are those that can have their adverse consequences mitigated simply by having a well-diversified portfolio of risk exposures. For example, having some factories located in nonearthquake areas or hotels placed in numerous locations in the United States diversifies the risk. If one property is damaged, the others are not subject to the same geographical phenomenon causing the risks. A large number of relatively homogeneous independent exposure units pooled together in a portfolio can make the average, or per exposure, unit loss much more predictable, and since these exposure units are independent of each other, the per-unit consequences of the risk can then be significantly reduced, sometimes to the point of being ignorable. These will be further explored in a later chapter about the tools to mitigate risks. Diversification is the core of the modern portfolio theory in finance and in insurance. Risks, which are idiosyncraticRisks viewed as being amenable to having their financial consequences reduced or eliminated by holding a well-diversified portfolio. (with particular characteristics that are not shared by all) in nature, are often viewed as being amenable to having their financial consequences reduced or eliminated by holding a well-diversified portfolio.

Systemic risks that are shared by all, on the other hand, such as global warming, or movements of the entire economy such as that precipitated by the credit crisis of fall 2008, are considered nondiversifiable. Every asset or exposure in the portfolio is affected. The negative effect does not go away by having more elements in the portfolio. This will be discussed in detail below and in later chapters. The field of risk management deals with both diversifiable and nondiversifiable risks. As the events of September 2008 have shown, contrary to some interpretations of financial theory, the idiosyncratic risks of some banks could not always be diversified away. These risks have shown they have the ability to come back to bite (and poison) the entire enterprise and others associated with them.

Table 1.3 "Examples of Risk Exposures by the Diversifiable and Nondiversifiable Categories" provides examples of risk exposures by the categories of diversifiable and nondiversifiable risk exposures. Many of them are self explanatory, but the most important distinction is whether the risk is unique or idiosyncratic to a firm or not. For example, the reputation of a firm is unique to the firm. Destroying one’s reputation is not a systemic risk in the economy or the market-place. On the other hand, market risk, such as devaluation of the dollar is systemic risk for all firms in the export or import businesses. In Table 1.3 "Examples of Risk Exposures by the Diversifiable and Nondiversifiable Categories" we provide examples of risks by these categories. The examples are not complete and the student is invited to add as many examples as desired.

Table 1.3 Examples of Risk Exposures by the Diversifiable and Nondiversifiable Categories

| Diversifiable Risk—Idiosyncratic Risk | Nondiversifiable Risks—Systemic Risk |

|---|---|

| • Reputational risk | • Market risk |

| • Brand risk | • Regulatory risk |

| • Credit risk (at the individual enterprise level) | • Environmental risk |

| • Product risk | • Political risk |

| • Legal risk | • Inflation and recession risk |

| • Physical damage risk (at the enterprise level) such as fire, flood, weather damage | • Accounting risk |

| • Liability risk (products liability, premise liability, employment practice liability) | • Longevity risk at the societal level |

| • Innovational or technical obsolesce risk | • Mortality and morbidity risk at the societal and global level (pandemics, social security program exposure, nationalize health care systems, etc.) |

| • Operational risk | |

| • Strategic risk | |

| • Longevity risk at the individual level | |

| • Mortality and morbidity risk at the individual level |

Enterprise Risks

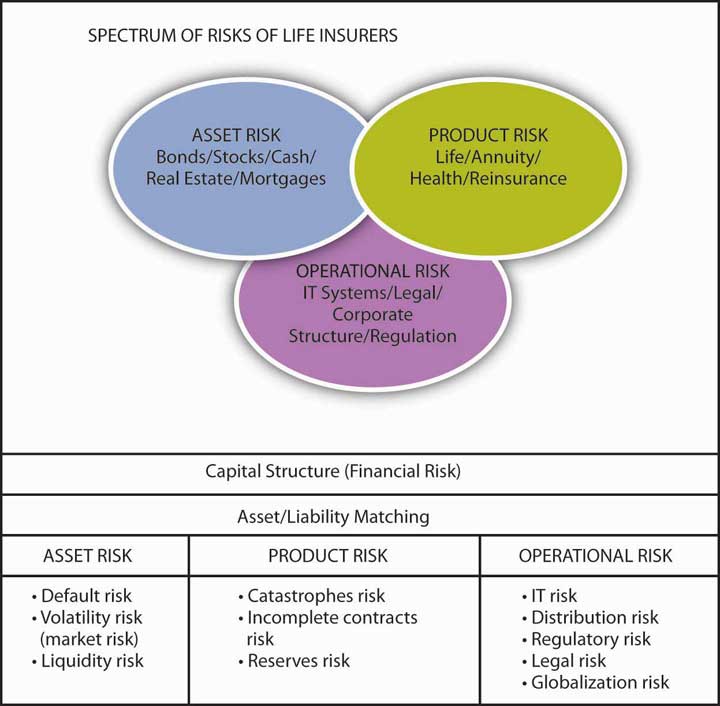

As discussed above, the opportunities in the risks and the fear of losses encompass the holistic risk or the enterprise risk of an entity. The following is an example of the enterprise risks of life insurers in a map in Figure 1.6 "Life Insurers’ Enterprise Risks".Etti G. Baranoff and Thomas W. Sager, “Integrated Risk Management in Life Insurance Companies,” an award winning paper, International Insurance Society Seminar, Chicago, July 2006 and in Special Edition of the Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance.

Since enterprise risk management is a key current concept today, the enterprise risk map of life insurers is offered here as an example. Operational risks include public relations risks, environmental risks, and several others not detailed in the map in Figure 1.4 "Risk Balls". Because operational risks are so important, they usually include a long list of risks from employment risks to the operations of hardware and software for information systems.

Figure 1.6 Life Insurers’ Enterprise Risks

Risks in the Limelight

Our great successes in innovation are also at the heart of the greatest risks of our lives. An ongoing concern is the electronic risk (e-risk) generated by the extensive use of computers, e-commerce, and the Internet. These risks are extensive and the exposures are becoming more defined. The box Note 1.32 "The Risks of E-exposures" below illustrates the newness and not-so-newness in our risks.

The Risks of E-exposures

Electronic risk, or e-risk, comes in many forms. Like any property, computers are vulnerable to theft and employee damage (accidental or malicious). Certain components are susceptible to harm from magnetic or electrical disturbance or extremes of temperature and humidity. More important than replaceable hardware or software is the data they store; theft of proprietary information costs companies billions of dollars. Most data theft is perpetrated by employees, but “netspionage”—electronic espionage by rival companies—is on the rise.

Companies that use the Internet commercially—who create and post content or sell services or merchandise—must follow the laws and regulations that traditional businesses do and are exposed to the same risks. An online newsletter or e-zine can be sued for libel, defamation, invasion of privacy, or misappropriation (e.g., reproducing a photograph without permission) under the same laws that apply to a print newspaper. Web site owners and companies conducting business over the Internet have three major exposures to protect: intellectual property (copyrights, patents, trade secrets); security (against viruses and hackers); and business continuity (in case of system crashes).

All of these losses are covered by insurance, right? Wrong. Some coverage is provided through commercial property and liability policies, but traditional insurance policies were not designed to include e-risks. In fact, standard policies specifically exclude digital risks (or provide minimal coverage). Commercial property policies cover physical damage to tangible assets—and computer data, software, programs, and networks are generally not counted as tangible property. (U.S. courts are still debating the issue.)

This coverage gap can be bridged either by buying a rider or supplemental coverage to the traditional policies or by purchasing special e-risk or e-commerce coverage. E-risk property policies cover damages to the insured’s computer system or Web site, including lost income because of a computer crash. An increasing number of insurers are offering e-commerce liability policies that offer protection in case the insured is sued for spreading a computer virus, infringing on property or intellectual rights, invading privacy, and so forth.

Cybercrime is just one of the e-risk-related challenges facing today’s risk managers. They are preparing for it as the world evolves faster around cyberspace, evidenced by record-breaking online sales during the 2005 Christmas season.

Sources: Harry Croydon, “Making Sense of Cyber-Exposures,” National Underwriter, Property & Casualty/Risk & Benefits Management Edition, 17 June 2002; Joanne Wojcik, “Insurers Cut E-Risks from Policies,” Business Insurance, 10 September 2001; Various media resources at the end of 2005 such as Wall Street Journal and local newspapers.

Today, there is no media that is not discussing the risks that brought us to the calamity we are enduring during our current financial crisis. Thus, as opposed to the megacatastrophes of 2001 and 2005, our concentration is on the failure of risk management in the area of speculative risks or the opportunity in risks and not as much on the pure risk. A case at point is the little media coverage of the devastation of Galveston Island from Hurricane Ike during the financial crisis of September 2008. The following box describes the risks of the first decade of the new millennium.

Risks in the New Millennium

While man-made and natural disasters are the stamps of this decade, another type of man-made disaster marks this period.Reprinted with permission from the author; Etti G. Baranoff, “Risk Management and Insurance During the Decade of September 11,” in The Day that Changed Everything? An Interdisciplinary Series of Edited Volumes on the Impact of 9/11, vol. 2. Innovative financial products without appropriate underwriting and risk management coupled with greed and lack of corporate controls brought us to the credit crisis of 2007 and 2008 and the deepest recession in a generation. The capital market has become an important player in the area of risk management with creative new financial instruments, such as Catastrophe Bonds and securitized instruments. However, the creativity and innovation also introduced new risky instruments, such as credit default swaps and mortgage-backed securities. Lack of careful underwriting of mortgages coupled with lack of understanding of the new creative “insurance” default swaps instruments and the resulting instability of the two largest remaining bond insurers are at the heart of the current credit crisis.

As such, within only one decade we see the escalation in new risk exposures at an accelerated rate. This decade can be named “the decade of extreme risks with inadequate risk management.” The late 1990s saw extreme risks with the stock market bubble without concrete financial theory. This was followed by the worst terrorist attack in a magnitude not experienced before on U.S. soil. The corporate corruption at extreme levels in corporations such as Enron just deepened the sense of extreme risks. The natural disasters of Katrina, Rita, and Wilma added to the extreme risks and were exacerbated by extraordinary mismanagement. Today, the extreme risks of mismanaged innovations in the financial markets combined with greed are stretching the field of risk management to new levels of governmental and private controls.

However, did the myopic concentration on terrorism risk derail the holistic view of risk management and preparedness? The aftermath of Katrina is a testimonial to the lack of risk management. The increase of awareness and usage of enterprise risk management (ERM) post–September 11 failed to encompass the already well-known risks of high-category hurricanes on the sustainability of New Orleans levies. The newly created holistic Homeland Security agency, which houses FEMA, not only did not initiate steps to avoid the disaster, it also did not take the appropriate steps to reduce the suffering of those afflicted once the risk materialized. This outcome also points to the importance of having a committed stakeholder who is vested in the outcome and cares to lower and mitigate the risk. Since the insurance industry did not own the risk of flood, there was a gap in the risk management. The focus on terrorism risk could be regarded as a contributing factor to the neglect of the natural disasters risk in New Orleans. The ground was fertile for mishandling the extreme hurricane catastrophes. Therefore, from such a viewpoint, it can be argued that September 11 derailed our comprehensive national risk management and contributed indirectly to the worsening of the effects of Hurricane Katrina.

Furthermore, in an era of financial technology and creation of innovative modeling for predicting the most infrequent catastrophes, the innovation and growth in human capacity is at the root of the current credit crisis. While the innovation allows firms such as Risk Management Solutions (RMS) and AIR Worldwide to provide modelshttp://www.rms.com, http://www.iso.com/index.php?option= com_content&task=view&id=932&Itemid=587, and http://www.iso.com/index.php?option= com_content&task=view&id=930&Itemid=585. that predict potential man-made and natural catastrophes, financial technology also advanced the creation of financial instruments, such as credit default derivatives and mortgage-backed securities. The creation of the products provided “black boxes” understood by few and without appropriate risk management. Engineers, mathematicians, and quantitatively talented people moved from the low-paying jobs in their respective fields into Wall Street. They used their skills to create models and new products but lacked the business acumen and the required safety net understanding to ensure product sustenance. Management of large financial institutions globally enjoyed the new creativity and endorsed the adoption of the new products without clear understanding of their potential impact or just because of greed. This lack of risk management is at the heart of the credit crisis of 2008. No wonder the credit rating organizations are now adding ERM scores to their ratings of companies.

The following quote is a key to today’s risk management discipline: “Risk management has been a significant part of the insurance industry…, but in recent times it has developed a wider currency as an emerging management philosophy across the globe…. The challenge facing the risk management practitioner of the twenty-first century is not just breaking free of the mantra that risk management is all about insurance, and if we have insurance, then we have managed our risks, but rather being accepted as a provider of advice and service to the risk makers and the risk takers at all levels within the enterprise. It is the risk makers and the risk takers who must be the owners of risk and accountable for its effective management.”Laurent Condamin, Jean-Paul Louisot, and Patrick Maim, “Risk Quantification: Management, Diagnosis and Hedging” (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2006).

Key Takeaways

- You should be able to delineate the main categories of risks: pure versus speculative, diversifiable versus nondiversifiable, idiosyncratic versus systemic.

- You should also understand the general concept of enterprise-wide risk.

- Try to illustrate each cross classification of risk with examples.

- Can you discuss the risks of our decade?

Discussion Questions

- Name the main categories of risks.

- Provide examples of risk categories.

- How would you classify the risks embedded in the financial crisis of fall 2008 within each of cross-classification?

- How does e-risk fit into the categories of risk?