This is “The Theory and Practice of Socialism”, section 34.1 from the book Economics Principles (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

34.1 The Theory and Practice of Socialism

Learning Objective

- Discuss and assess Karl Marx’s theory of capitalism, including mention of the labor theory of value, the concept of surplus value, periodic capitalist crises, and worker solidarity.

Socialism has a very long history. The earliest recorded socialist society is described in the Book of Acts in the Bible. Following the crucifixion of Jesus, Christians in Jerusalem established a system in which all property was owned in common.

There have been other socialist experiments in which all property was held in common, effectively creating socialist societies. Early in the nineteenth century, such reformers as Robert Owen, Count Claude-Henri de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon, and Charles Fourier established almost 200 communities in which workers shared in the proceeds of their labor. These men, while operating independently, shared a common ideal—that in the appropriate economic environment, people will strive for the good of the community rather than for their own self-interest. Although some of these communities enjoyed a degree of early success, none survived.

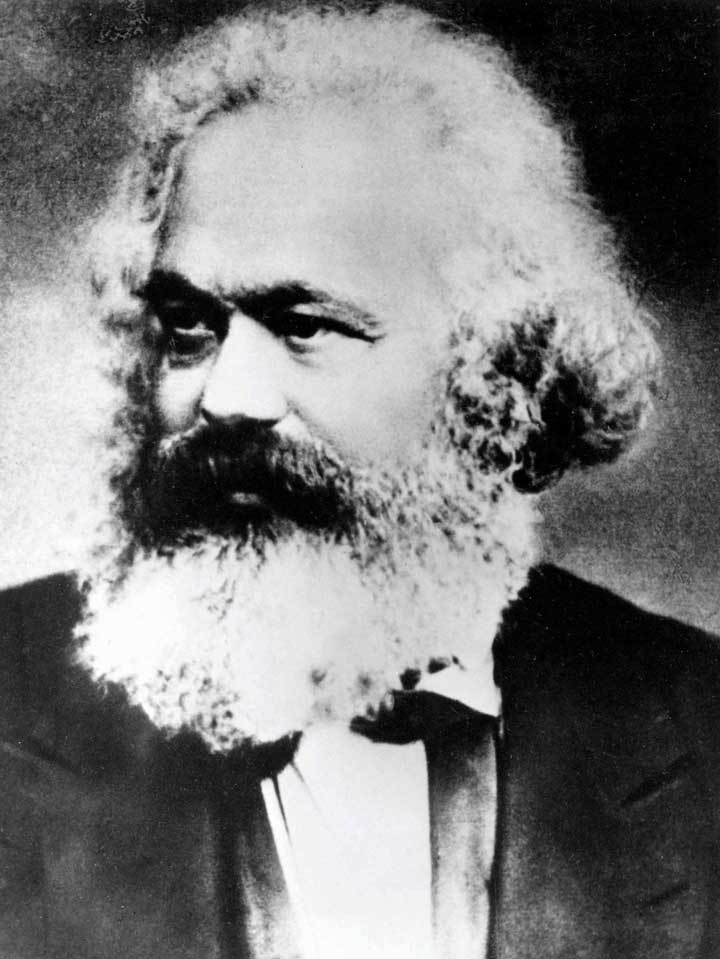

Socialism as the organizing principle for a national economy is in large part the product of the revolutionary ideas of one man, Karl Marx. His analysis of what he saw as the inevitable collapse of market capitalist economies provided a rallying spark for the national socialist movements of the twentieth century. Another important contributor to socialist thought was Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who modified many of Marx’s theories for application to the Soviet Union. Lenin put his ideas into practice as dictator of that country from 1917 until his death in 1924. It fell to Joseph Stalin to actually implement the Soviet system. We shall examine the ideas of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin and investigate the operation of the economic systems based upon them.

The Economics of Karl Marx

Marx is perhaps best known for the revolutionary ideas expressed in the ringing phrases of the Communist Manifesto, such as those shown in the Case in Point. Written with Friedrich Engels in 1848, the Manifesto was a call to arms. But it was Marx’s exhaustive, detailed theoretical analysis of market capitalism, Das Kapital (Capital), that was his most important effort. This four-volume work, most of which was published after Marx’s death, examines a theoretical economy that we would now describe as perfect competition. In this context, Marx outlined a dynamic process that would, he argued, inevitably result in the collapse of capitalism.

Marx stressed a historical approach to the analysis of economics. Indeed, he was sharply critical of his contemporaries, complaining that their work was wholly lacking in historical perspective. To Marx, capitalism was merely a stage in the development of economic systems. He explained how feudalism would tend to give way to capitalism and how capitalism would give way to socialism. Marx’s conclusions stemmed from his labor theory of value and from his perception of the role of profit in a capitalist economy.

The Labor Theory of Value and Surplus Value

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith proposed the idea of the labor theory of valueTheory that states that the relative values of different goods are ultimately determined by the relative amounts of labor used in their production., which states that the relative values of different goods are ultimately determined by the relative amounts of labor used in their production. This idea was widely accepted at the time Marx was writing. Economists recognized the roles of demand and supply but argued that these would affect prices only in the short run. In the long run, it was labor that determined value.

Marx attached normative implications to the ideas of the labor theory of value. Not only was labor the ultimate determinant of value, it was the only legitimate determinant of value. The price of a good in Marx’s system equaled the sum of the labor and capital costs of its production, plus profit to the capitalist. Marx argued that capital costs were determined by the amount of labor used to produce the capital, so the price of a good equaled a return to labor plus profit. Marx defined profit as surplus valueThe difference between the price of a good or service and the labor cost of producing it., the difference between the price of a good or service and the labor cost of producing it. Marx insisted that surplus value was unjustified and represented exploitation of workers.

Marx accepted another piece of conventional economic wisdom of the nineteenth century, the concept of subsistence wages. This idea held that wages would, in the long run, tend toward their subsistence level, a level just sufficient to keep workers alive. Any increase in wages above their subsistence level would simply attract more workers—or induce an increase in population, forcing wages back down. Marx suggested that unemployed workers were important in this process; they represented a surplus of labor that acted to push wages down.

Capital Accumulation and Capitalist Crises

The concepts of surplus value and subsistence wages provide the essential dynamics of Marx’s system. He said that capitalists, in an effort to increase surplus value, would seek to acquire more capital. But as they expanded capital, their profit rates, expressed as a percentage of the capital they held, would fall. In a desperate effort to push profit rates up, capitalists would acquire still more capital, which would only push their rate of return down further.

A further implication of Marx’s scheme was that as capitalists increased their use of capital, the wages received by workers would become a smaller share of the total value of goods. Marx assumed that capitalists used all their funds to acquire more capital. Only workers, then, could be counted on for consumption. But their wages equaled only a fraction of the value of the output they produced—they could not possibly buy all of it. The result, Marx said, would be a series of crises in which capitalists throughout the economy, unable to sell their output, would cut back production. This would cause still more reductions in demand, exacerbating the downturn in economic activity. Crises would drive the weakest capitalists out of business; they would become unemployed and thus push wages down further. The economy could recover from such crises, but each one would weaken the capitalist system.

Faced with declining surplus values and reeling from occasional crises, capitalists would seek out markets in other countries. As they extended their reach throughout the world, Marx said, the scope of their exploitation of workers would expand. Although capitalists could make temporary gains by opening up international markets, their continuing acquisition of capital meant that profit rates would resume their downward trend. Capitalist crises would now become global affairs.

According to Marx, another result of capitalists’ doomed efforts to boost surplus value would be increased solidarity among the working class. At home, capitalist acquisition of capital meant workers would be crowded into factories, building their sense of class identity. As capitalists extended their exploitation worldwide, workers would gain a sense of solidarity with fellow workers all over the planet. Marx argued that workers would recognize that they were the victims of exploitation by capitalists.

Marx was not clear about precisely what forces would combine to bring about the downfall of capitalism. He suggested other theories of crisis in addition to the one based on insufficient demand for the goods and services produced by capitalists. Indeed, modern theories of the business cycle owe much to Marx’s discussion of the possible sources of economic downturns. Although Marx spoke sometimes of bloody revolution, it is not clear that this was the mechanism he thought would bring on the demise of capitalism. Whatever the precise mechanism, Marx was confident that capitalism would fall, that its collapse would be worldwide, and that socialism would replace it.

Marx’s Theory: An Assessment

To a large degree, Marx’s analysis of a capitalist economy was a logical outgrowth of widely accepted economic doctrines of his time. As we have seen, the labor theory of value was conventional wisdom, as was the notion that workers would receive only a subsistence wage. The notion that profit rates would fall over time was widely accepted. Doctrines similar to Marx’s notion of recurring crises had been developed by several economists of the period.

What was different about Marx was his tracing of the dynamics of a system in which values would be determined by the quantity of labor, wages would tend toward the subsistence level, profit rates would fall, and crises would occur from time to time. Marx saw these forces as leading inevitably to the fall of capitalism and its replacement with a socialist economic system. Other economists of the period generally argued that economies would stagnate; they did not anticipate the collapse predicted by Marx.

Marx’s predictions have turned out to be wildly off the mark. Profit rates have not declined; they have remained relatively stable over the long run. Wages have not tended downward toward their subsistence level; they have risen. Labor’s share of total income in market economies has not fallen; it has increased. Most important, the predicted collapse of capitalist economies has not occurred.

Revolutions aimed at establishing socialism have been rare. Perhaps most important, none has occurred in a market capitalist economy. The Cuban economy, for example, had some elements of market capitalism before Castro but also had features of command systems as well.While resources in Cuba were generally privately owned, the government had broad powers to dictate their use. In other cases where socialism has been established through revolution it has replaced systems that could best be described as feudal. The Russian Revolution of 1917 that established the Soviet Union and the revolution that established the People’s Republic of China in 1949 are the most important examples of this form of revolution. In the countries of Eastern Europe, socialism was imposed by the former Soviet Union in the wake of World War II. In the early 2000s, a number of Latin American countries, such as Venezuela and Bolivia, seemed to be moving towards nationalizing, rather than privatizing assets, but it is too early to know the long-term direction of these economies.

Whatever the shortcomings of Marx’s economic prognostications, his ideas have had enormous influence. Politically, his concept of the inevitable emergence of socialism promoted the proliferation of socialist-leaning governments during the middle third of the twentieth century. Before socialist systems began collapsing in 1989, fully one-third of the earth’s population lived in countries that had adopted Marx’s ideas. Ideologically, his vision of a market capitalist system in which one class exploits another has had enormous influence.

Key Takeaways

- Marx’s theory, based on the labor theory of value and the presumption that wages would approach the subsistence level, predicted the inevitable collapse of capitalism and its replacement by socialist regimes.

- Lenin modified many of Marx’s theories for application to the Soviet Union and put his ideas into practice as dictator of that country from 1917 until his death in 1924.

- Before socialist systems began collapsing in 1989, fully one-third of the earth’s population lived in countries that had adopted Marx’s ideas.

Try It!

Briefly explain how each of the following would contribute to the downfall of capitalism: 1) capital accumulation, 2) subsistence wages, and 3) the factory system.

Case in Point: The Powerful Images in the Communist Manifesto

Figure 34.1

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels was originally published in London in 1848, a year in which there were a number of uprisings across Europe that at the time could have been interpreted as the beginning of the end of capitalism. This relatively short (12,000 words) document was thus more than an analysis of the process of historical change, in which class struggles propel societies from one type of economic system to the next, and a prediction about how capitalism would evolve and why it would end. It was also a call to action. It contains powerful images that cannot be easily forgotten. It begins,

“A specter is haunting Europe—the specter of communism. All the Powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this specter: Pope and Czar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.”

Its description of history begins,

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another …”

In capitalism, the divisions are yet more stark:

“Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other: Bourgeoisie and Proletariat.”

Foreshadowing the globalization of capitalism, Marx and Engels wrote,

“The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production: it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst. … In one word, it creates a world after its own image.”

But the system, like all other class-based systems before it, brings about its own demise:

“The weapons with which the bourgeoisie felled feudalism to the ground are now turned against the bourgeoisie itself. … Masses of laborers, crowded into the factory, are organized like soldiers. … It was just this contact that was needed to centralize the numerous local struggles, all of the same character, into one national struggle between classes.”

The national struggles eventually become an international struggle in which:

“What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces, above all, is its own gravediggers.”

The Manifesto ends,

“Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. WORKING MEN OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE!”

Answer to Try It!

Marx predicted that capital accumulation would lead to falling profit rates over the long term. Subsistence wages meant that workers would not be able to consume enough of what was produced and this would lead to ever larger economic downturns. Because of the factory system, worker solidarity would grow and workers would come to understand that they were being exploited by capitalists.