This is “Recessionary and Inflationary Gaps and Long-Run Macroeconomic Equilibrium”, section 22.3 from the book Economics Principles (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

22.3 Recessionary and Inflationary Gaps and Long-Run Macroeconomic Equilibrium

Learning Objectives

- Explain and illustrate graphically recessionary and inflationary gaps and relate these gaps to what is happening in the labor market.

- Identify the various policy choices available when an economy experiences an inflationary or recessionary gap and discuss some of the pros and cons that make these choices controversial.

The intersection of the economy’s aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves determines equilibrium real GDP and price level in the short run. The intersection of aggregate demand and long-run aggregate supply determines its long-run equilibrium. In this section we will examine the process through which an economy moves from equilibrium in the short run to equilibrium in the long run.

The long run puts a nation’s macroeconomic house in order: only frictional and structural unemployment remain, and the price level is stabilized. In the short run, stickiness of nominal wages and other prices can prevent the economy from achieving its potential output. Actual output may exceed or fall short of potential output. In such a situation the economy operates with a gap. When output is above potential, employment is above the natural level of employment. When output is below potential, employment is below the natural level.

Recessionary and Inflationary Gaps

At any time, real GDP and the price level are determined by the intersection of the aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves. If employment is below the natural level of employment, real GDP will be below potential. The aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves will intersect to the left of the long-run aggregate supply curve.

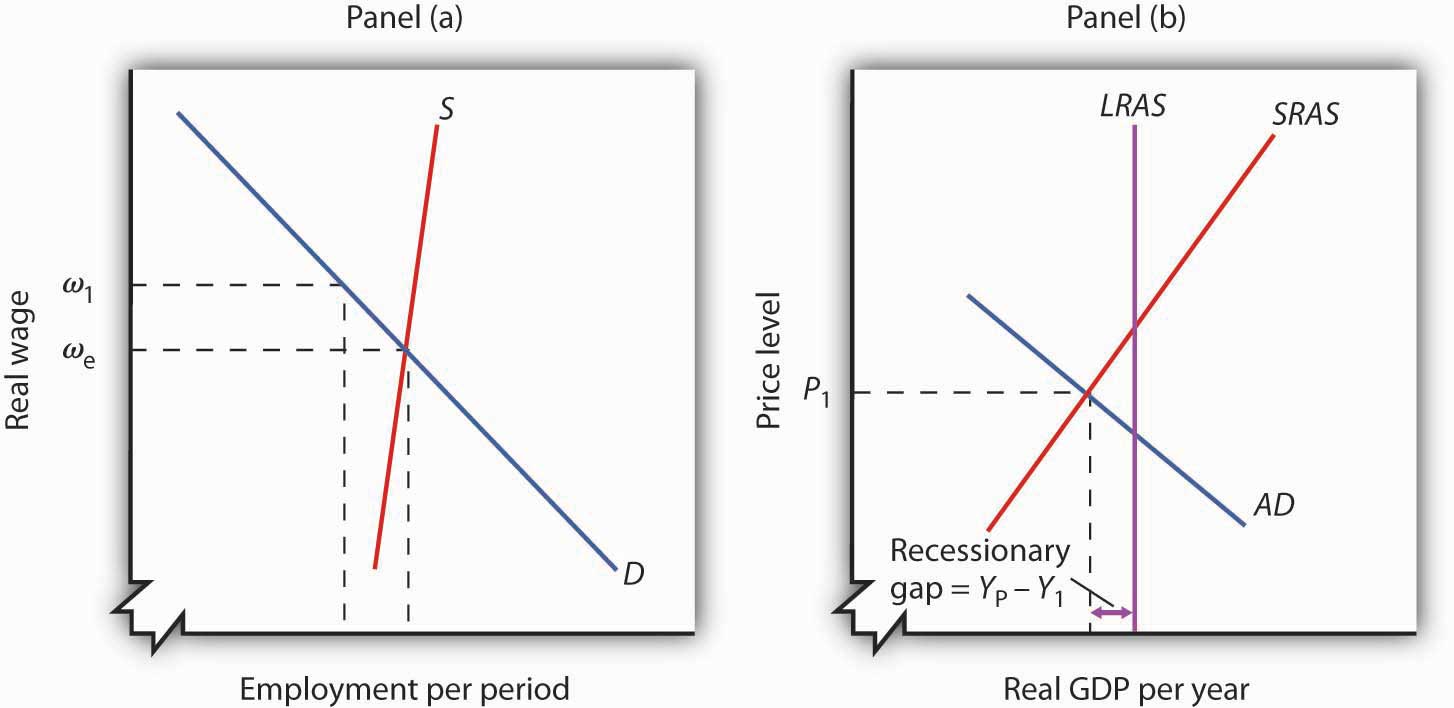

Suppose an economy’s natural level of employment is Le, shown in Panel (a) of Figure 22.13 "A Recessionary Gap". This level of employment is achieved at a real wage of ωe. Suppose, however, that the initial real wage ω1 exceeds this equilibrium value. Employment at L1 falls short of the natural level. A lower level of employment produces a lower level of output; the aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves, AD and SRAS, intersect to the left of the long-run aggregate supply curve LRAS in Panel (b). The gap between the level of real GDP and potential output, when real GDP is less than potential, is called a recessionary gapThe gap between the level of real GDP and potential output, when real GDP is less than potential..

Figure 22.13 A Recessionary Gap

If employment is below the natural level, as shown in Panel (a), then output must be below potential. Panel (b) shows the recessionary gap YP − Y1, which occurs when the aggregate demand curve AD and the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS intersect to the left of the long-run aggregate supply curve LRAS.

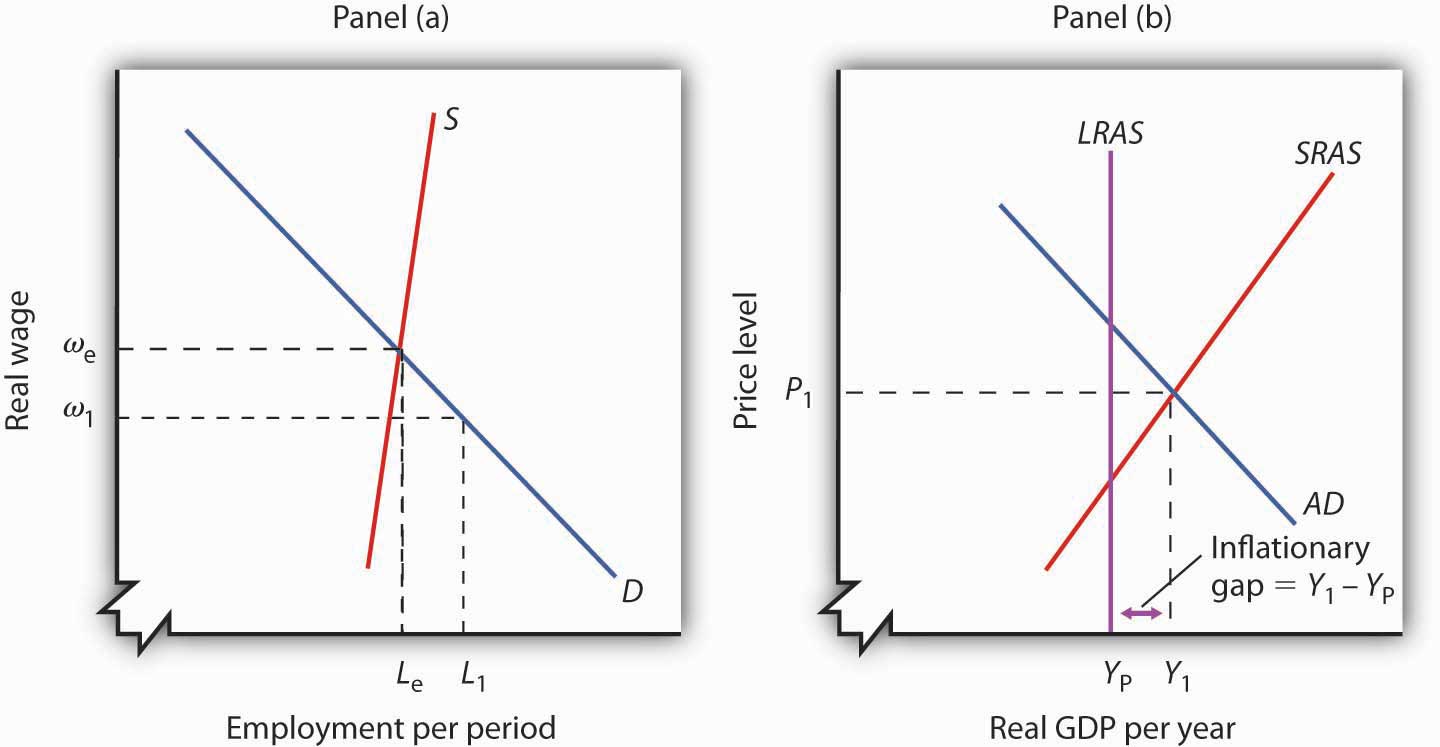

Just as employment can fall short of its natural level, it can also exceed it. If employment is greater than its natural level, real GDP will also be greater than its potential level. Figure 22.14 "An Inflationary Gap" shows an economy with a natural level of employment of Le in Panel (a) and potential output of YP in Panel (b). If the real wage ω1 is less than the equilibrium real wage ωe, then employment L1 will exceed the natural level. As a result, real GDP, Y1, exceeds potential. The gap between the level of real GDP and potential output, when real GDP is greater than potential, is called an inflationary gapThe gap between the level of real GDP and potential output, when real GDP is greater than potential.. In Panel (b), the inflationary gap equals Y1 − YP.

Figure 22.14 An Inflationary Gap

Panel (a) shows that if employment is above the natural level, then output must be above potential. The inflationary gap, shown in Panel (b), equals Y1 − YP. The aggregate demand curve AD and the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS intersect to the right of the long-run aggregate supply curve LRAS.

Restoring Long-Run Macroeconomic Equilibrium

We have already seen that the aggregate demand curve shifts in response to a change in consumption, investment, government purchases, or net exports. The short-run aggregate supply curve shifts in response to changes in the prices of factors of production, the quantities of factors of production available, or technology. Now we will see how the economy responds to a shift in aggregate demand or short-run aggregate supply using two examples presented earlier: a change in government purchases and a change in health-care costs. By returning to these examples, we will be able to distinguish the long-run response from the short-run response.

A Shift in Aggregate Demand: An Increase in Government Purchases

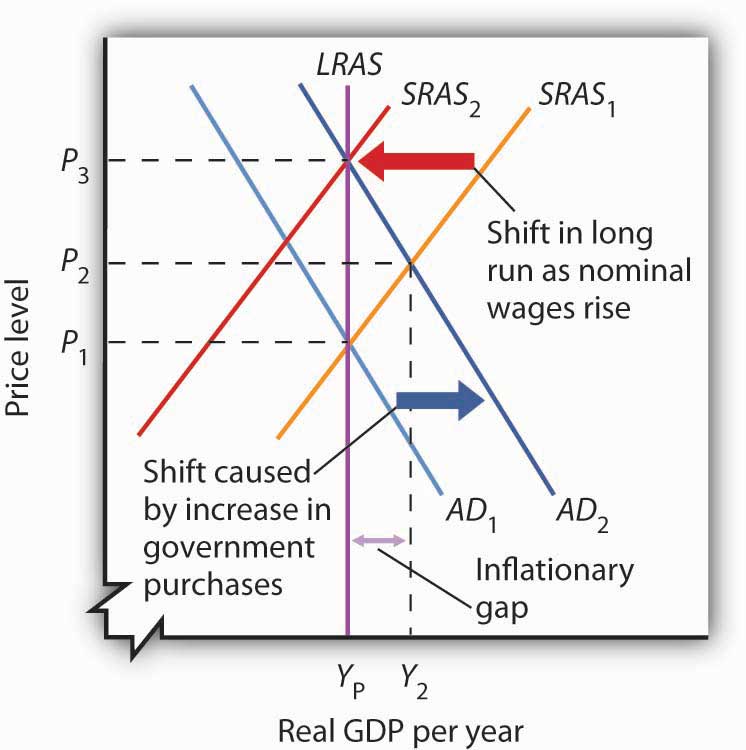

Suppose an economy is initially in equilibrium at potential output YP as in Figure 22.15 "Long-Run Adjustment to an Inflationary Gap". Because the economy is operating at its potential, the labor market must be in equilibrium; the quantities of labor demanded and supplied are equal.

Figure 22.15 Long-Run Adjustment to an Inflationary Gap

An increase in aggregate demand to AD2 boosts real GDP to Y2 and the price level to P2, creating an inflationary gap of Y2 − YP. In the long run, as price and nominal wages increase, the short-run aggregate supply curve moves to SRAS2. Real GDP returns to potential.

Now suppose aggregate demand increases because one or more of its components (consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports) has increased at each price level. For example, suppose government purchases increase. The aggregate demand curve shifts from AD1 to AD2 in Figure 22.15 "Long-Run Adjustment to an Inflationary Gap". That will increase real GDP to Y2 and force the price level up to P2 in the short run. The higher price level, combined with a fixed nominal wage, results in a lower real wage. Firms employ more workers to supply the increased output.

The economy’s new production level Y2 exceeds potential output. Employment exceeds its natural level. The economy with output of Y2 and price level of P2 is only in short-run equilibrium; there is an inflationary gap equal to the difference between Y2 and YP. Because real GDP is above potential, there will be pressure on prices to rise further.

Ultimately, the nominal wage will rise as workers seek to restore their lost purchasing power. As the nominal wage rises, the short-run aggregate supply curve will begin shifting to the left. It will continue to shift as long as the nominal wage rises, and the nominal wage will rise as long as there is an inflationary gap. These shifts in short-run aggregate supply, however, will reduce real GDP and thus begin to close this gap. When the short-run aggregate supply curve reaches SRAS2, the economy will have returned to its potential output, and employment will have returned to its natural level. These adjustments will close the inflationary gap.

A Shift in Short-Run Aggregate Supply: An Increase in the Cost of Health Care

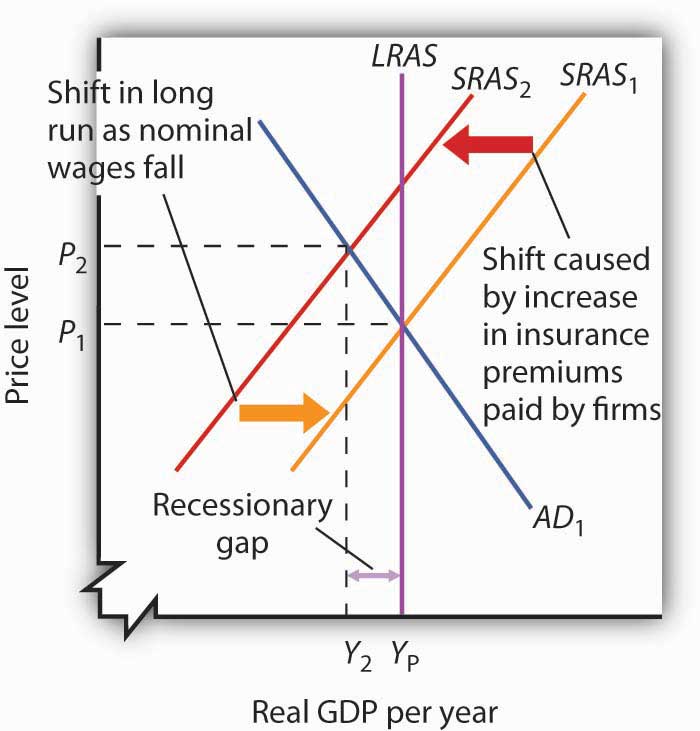

Again suppose, with an aggregate demand curve at AD1 and a short-run aggregate supply at SRAS1, an economy is initially in equilibrium at its potential output YP, at a price level of P1, as shown in Figure 22.16 "Long-Run Adjustment to a Recessionary Gap". Now suppose that the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts owing to a rise in the cost of health care. As we explained earlier, because health insurance premiums are paid primarily by firms for their workers, an increase in premiums raises the cost of production and causes a reduction in the short-run aggregate supply curve from SRAS1 to SRAS2.

Figure 22.16 Long-Run Adjustment to a Recessionary Gap

A decrease in aggregate supply from SRAS1 to SRAS2 reduces real GDP to Y2 and raises the price level to P2, creating a recessionary gap of YP − Y2. In the long run, as prices and nominal wages decrease, the short-run aggregate supply curve moves back to SRAS1 and real GDP returns to potential.

As a result, the price level rises to P2 and real GDP falls to Y2. The economy now has a recessionary gap equal to the difference between YP and Y2. Notice that this situation is particularly disagreeable, because both unemployment and the price level rose.

With real GDP below potential, though, there will eventually be pressure on the price level to fall. Increased unemployment also puts pressure on nominal wages to fall. In the long run, the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts back to SRAS1. In this case, real GDP returns to potential at YP, the price level falls back to P1, and employment returns to its natural level. These adjustments will close the recessionary gap.

How sticky prices and nominal wages are will determine the time it takes for the economy to return to potential. People often expect the government or the central bank to respond in some way to try to close gaps. This issue is addressed next.

Gaps and Public Policy

If the economy faces a gap, how do we get from that situation to potential output?

Gaps present us with two alternatives. First, we can do nothing. In the long run, real wages will adjust to the equilibrium level, employment will move to its natural level, and real GDP will move to its potential. Second, we can do something. Faced with a recessionary or an inflationary gap, policy makers can undertake policies aimed at shifting the aggregate demand or short-run aggregate supply curves in a way that moves the economy to its potential. A policy choice to take no action to try to close a recessionary or an inflationary gap, but to allow the economy to adjust on its own to its potential output, is a nonintervention policyA policy choice to take no action to try to close a recessionary or an inflationary gap, but to allow the economy to adjust on its own to its potential output.. A policy in which the government or central bank acts to move the economy to its potential output is called a stabilization policyA policy in which the government or central bank acts to move the economy to its potential output..

Nonintervention or Expansionary Policy?

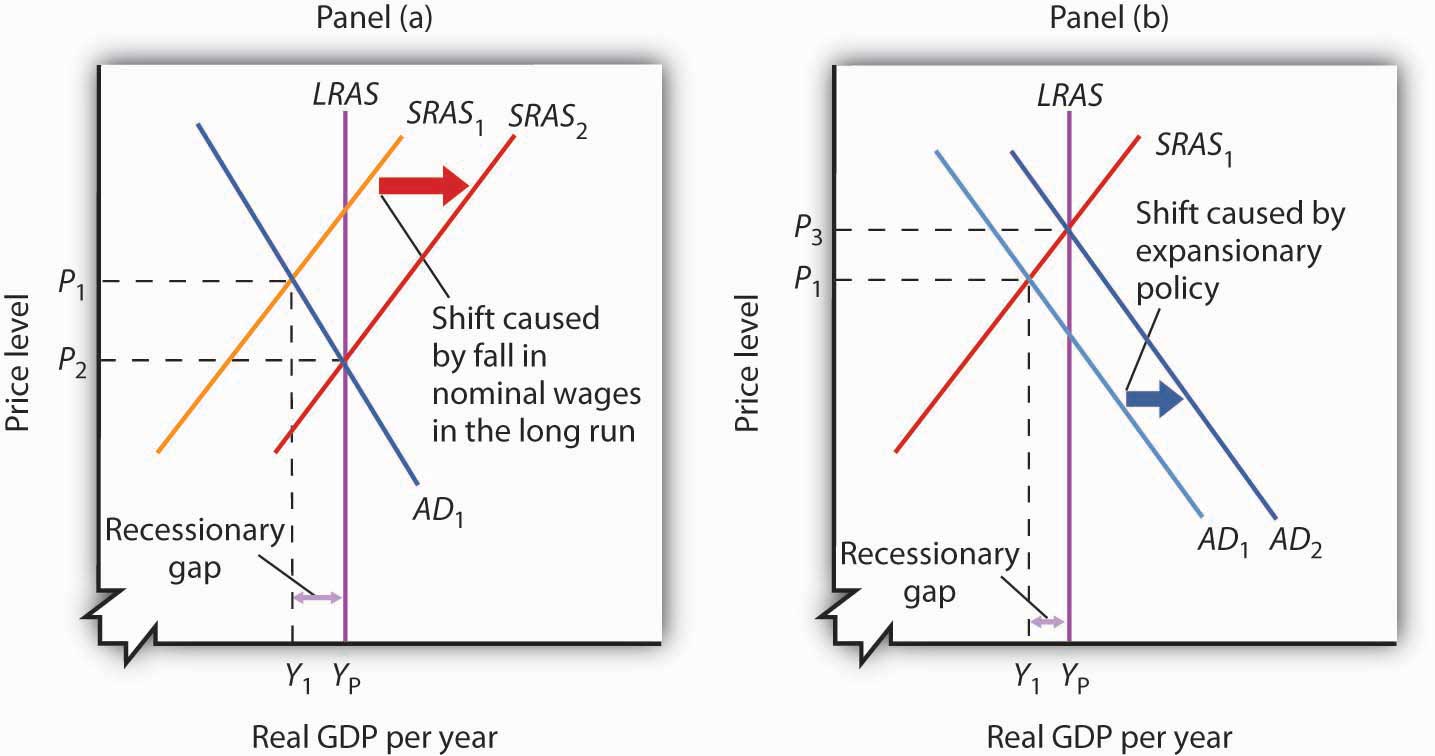

Figure 22.17 "Alternatives in Closing a Recessionary Gap" illustrates the alternatives for closing a recessionary gap. In both panels, the economy starts with a real GDP of Y1 and a price level of P1. There is a recessionary gap equal to YP − Y1. In Panel (a), the economy closes the gap through a process of self-correction. Real and nominal wages will fall as long as employment remains below the natural level. Lower nominal wages shift the short-run aggregate supply curve. The process is a gradual one, however, given the stickiness of nominal wages, but after a series of shifts in the short-run aggregate supply curve, the economy moves toward equilibrium at a price level of P2 and its potential output of YP.

Figure 22.17 Alternatives in Closing a Recessionary Gap

Panel (a) illustrates a gradual closing of a recessionary gap. Under a nonintervention policy, short-run aggregate supply shifts from SRAS1 to SRAS2. Panel (b) shows the effects of expansionary policy acting on aggregate demand to close the gap.

Panel (b) illustrates the stabilization alternative. Faced with an economy operating below its potential, public officials act to stimulate aggregate demand. For example, the government can increase government purchases of goods and services or cut taxes. Tax cuts leave people with more after-tax income to spend, boost their consumption, and increase aggregate demand. As AD1 shifts to AD2 in Panel (b) of Figure 22.17 "Alternatives in Closing a Recessionary Gap", the economy achieves output of YP, but at a higher price level, P3. A stabilization policy designed to increase real GDP is known as an expansionary policyA stabilization policy designed to increase real GDP..

Nonintervention or Contractionary Policy?

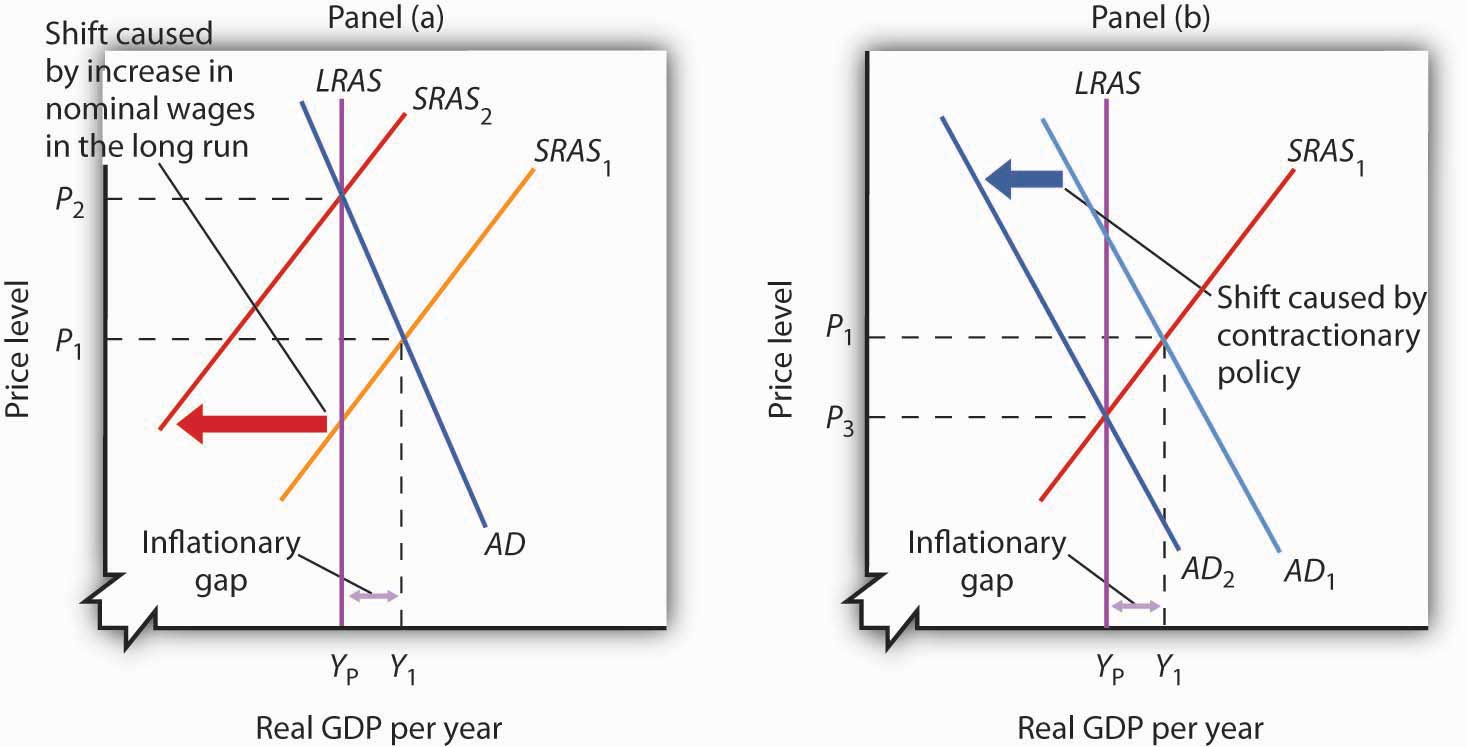

Figure 22.18 "Alternatives in Closing an Inflationary Gap" illustrates the alternatives for closing an inflationary gap. Employment in an economy with an inflationary gap exceeds its natural level—the quantity of labor demanded exceeds the long-run supply of labor. A nonintervention policy would rely on nominal wages to rise in response to the shortage of labor. As nominal wages rise, the short-run aggregate supply curve begins to shift, as shown in Panel (a), bringing the economy to its potential output when it reaches SRAS2 and P2.

Figure 22.18 Alternatives in Closing an Inflationary Gap

Panel (a) illustrates a gradual closing of an inflationary gap. Under a nonintervention policy, short-run aggregate supply shifts from SRAS1 to SRAS2. Panel (b) shows the effects of contractionary policy to reduce aggregate demand from AD1 to AD2 in order to close the gap.

A stabilization policy that reduces the level of GDP is a contractionary policyA stabilization policy designed to reduce real GDP.. Such a policy would aim at shifting the aggregate demand curve from AD1 to AD2 to close the gap, as shown in Panel (b). A policy to shift the aggregate demand curve to the left would return real GDP to its potential at a price level of P3.

For both kinds of gaps, a combination of letting market forces in the economy close part of the gap and of using stabilization policy to close the rest of the gap is also an option. Later chapters will explain stabilization policies in more detail, but there are essentially two types of stabilization policy: fiscal policy and monetary policy. Fiscal policyThe use of government purchases, transfer payments, and taxes to influence the level of economic activity. is the use of government purchases, transfer payments, and taxes to influence the level of economic activity. Monetary policyThe use of central bank policies to influence the level of economic activity. is the use of central bank policies to influence the level of economic activity.

To Intervene or Not to Intervene: An Introduction to the Controversy

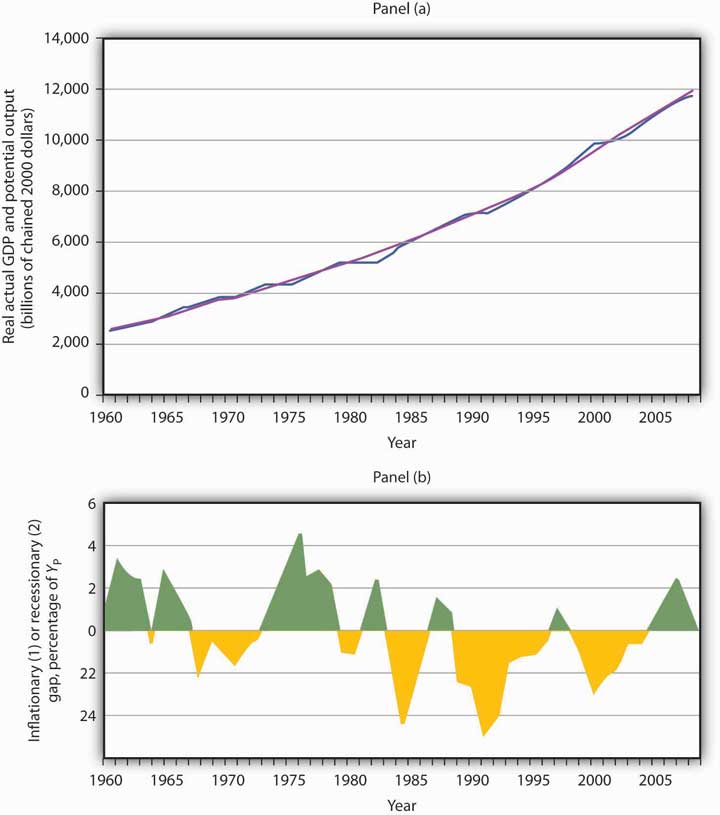

How large are inflationary and recessionary gaps? Panel (a) of Figure 22.19 "Real GDP and Potential Output" shows potential output versus the actual level of real GDP in the United States since 1960. Real GDP appears to follow potential output quite closely, although you see some periods where there have been inflationary or recessionary gaps. Panel (b) shows the sizes of these gaps expressed as percentages of potential output. The percentage gap is positive during periods of inflationary gaps and negative during periods of recessionary gaps. The economy seldom departs by more than 5% from its potential output.

Figure 22.19 Real GDP and Potential Output

Panel (a) shows potential output (the blue line) and actual real GDP (the purple line) since 1960. Panel (b) shows the gap between potential and actual real GDP expressed as a percentage of potential output. Inflationary gaps are shown in green and recessionary gaps are shown in yellow.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 1.1.6. Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars [Billions of chained (2000) dollars]. Seasonally adjusted at annual rates 2008 is through 3rd quarter; Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook, September 9, 2008.

Panel (a) gives a long-run perspective on the economy. It suggests that the economy generally operates at about potential output. In Panel (a), the gaps seem minor. Panel (b) gives a short-run perspective; the view it gives emphasizes the gaps. Both of these perspectives are important. While it is reassuring to see that the economy is often close to potential, the years in which there are substantial gaps have real effects: Inflation or unemployment can harm people.

Some economists argue that stabilization policy can and should be used when recessionary or inflationary gaps exist. Others urge reliance on the economy’s own ability to correct itself. They sometimes argue that the tools available to the public sector to influence aggregate demand are not likely to shift the curve, or they argue that the tools would shift the curve in a way that could do more harm than good.

Economists who advocate stabilization policies argue that prices are sufficiently sticky that the economy’s own adjustment to its potential will be a slow process—and a painful one. For an economy with a recessionary gap, unacceptably high levels of unemployment will persist for too long a time. For an economy with an inflationary gap, the increased prices that occur as the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts upward impose too high an inflation rate in the short run. These economists believe it is far preferable to use stabilization policy to shift the aggregate demand curve in an effort to shorten the time the economy is subject to a gap.

Economists who favor a nonintervention approach accept the notion that stabilization policy can shift the aggregate demand curve. They argue, however, that such efforts are not nearly as simple in the real world as they may appear on paper. For example, policies to change real GDP may not affect the economy for months or even years. By the time the impact of the stabilization policy occurs, the state of the economy might have changed. Policy makers might choose an expansionary policy when a contractionary one is needed or vice versa. Other economists who favor nonintervention also question how sticky prices really are and if gaps even exist.

The debate over how policy makers should respond to recessionary and inflationary gaps is an ongoing one. These issues of nonintervention versus stabilization policies lie at the heart of the macroeconomic policy debate. We will return to them as we continue our analysis of the determination of output and the price level.

Key Takeaways

- When the aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves intersect below potential output, the economy has a recessionary gap. When they intersect above potential output, the economy has an inflationary gap.

- Inflationary and recessionary gaps are closed as the real wage returns to equilibrium, where the quantity of labor demanded equals the quantity supplied. Because of nominal wage and price stickiness, however, such an adjustment takes time.

- When the economy has a gap, policy makers can choose to do nothing and let the economy return to potential output and the natural level of employment on its own. A policy to take no action to try to close a gap is a nonintervention policy.

- Alternatively, policy makers can choose to try to close a gap by using stabilization policy. Stabilization policy designed to increase real GDP is called expansionary policy. Stabilization policy designed to decrease real GDP is called contractionary policy.

Try It!

Using the scenario of the Great Depression of the 1930s, as analyzed in the previous Try It!, tell what kind of gap the U.S. economy faced in 1933, assuming the economy had been at potential output in 1929. Do you think the unemployment rate was above or below the natural rate of unemployment? How could the economy have been brought back to its potential output?

Case in Point: Survey of Economists Reveals Little Consensus on Macroeconomic Policy Issues

Figure 22.20

“An economy in short-run equilibrium at a real GDP below potential GDP has a self-correcting mechanism that will eventually return it to potential real GDP.”

Of economists surveyed, 36% disagreed, 33% agreed with provisos, 25% agreed, and 5% did not respond. So, only about 60% of economists responding to the survey agreed that the economy would adjust on its own.

“Changes in aggregate demand affect real GDP in the short run but not in the long run.”

On this statement, 36% disagreed, 31% agreed with provisos, 29% agreed, and 4% did not respond. Once again, about 60% of economists accepted the conclusion of the aggregate demand–aggregate supply model.

This level of disagreement on macroeconomic policy issues among economists, based on a fall 2000 survey of members of the American Economic Association, stands in sharp contrast to their more harmonious responses to questions on international economics and microeconomics. For example,

“Tariffs and import quotas usually reduce the general welfare of society.”

Seventy-two percent of those surveyed agreed with this statement outright and another 21% agreed with provisos. So, 93% of economists generally agreed with the statement.

“Minimum wages increase unemployment among young and unskilled workers.”

On this, 45% agreed and 29% agreed with provisos.

“Pollution taxes or marketable pollution permits are a more economically efficient approach to pollution control than emission standards.”

On this environmental question, only 6% disagreed and 63% wholeheartedly agreed.

The relatively low degree of consensus on macroeconomic policy issues and the higher degrees of consensus on other economic issues found in this survey concur with results of other periodic surveys since 1976.

So, as textbook authors, we will not hide the dirty laundry from you. Fortunately, though, the model of aggregate demand–aggregate supply we present throughout the macroeconomic chapters can handle most of these disagreements. For example, economists who agree with the first proposition quoted above, that an economy operating below potential has self-correcting mechanisms to bring it back to potential, are probably assuming that wages and prices are not very sticky and hence that the short-run aggregate supply curve will shift rather easily to the right, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 22.17 "Alternatives in Closing a Recessionary Gap". In contrast, economists who disagree with the statement are saying that the movement of the short-run aggregate supply curve is likely to be slow. This latter group of economists probably advocates expansionary policy as shown in Panel (b) of Figure 22.17 "Alternatives in Closing a Recessionary Gap". Both groups of economists can use the same model and its constructs to analyze the macroeconomy, but they may disagree on such things as the slopes of the various curves, on how fast these various curves shift, and on the size of the underlying multiplier. The model allows economists to speak the same language of analysis even though they disagree on some specifics.

Source: Dan Fuller and Doris Geide-Stevenson, “Consensus on Economic Issues: A Survey of Republicans, Democrats and Economists,” Eastern Economic Journal 33, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 81–94.

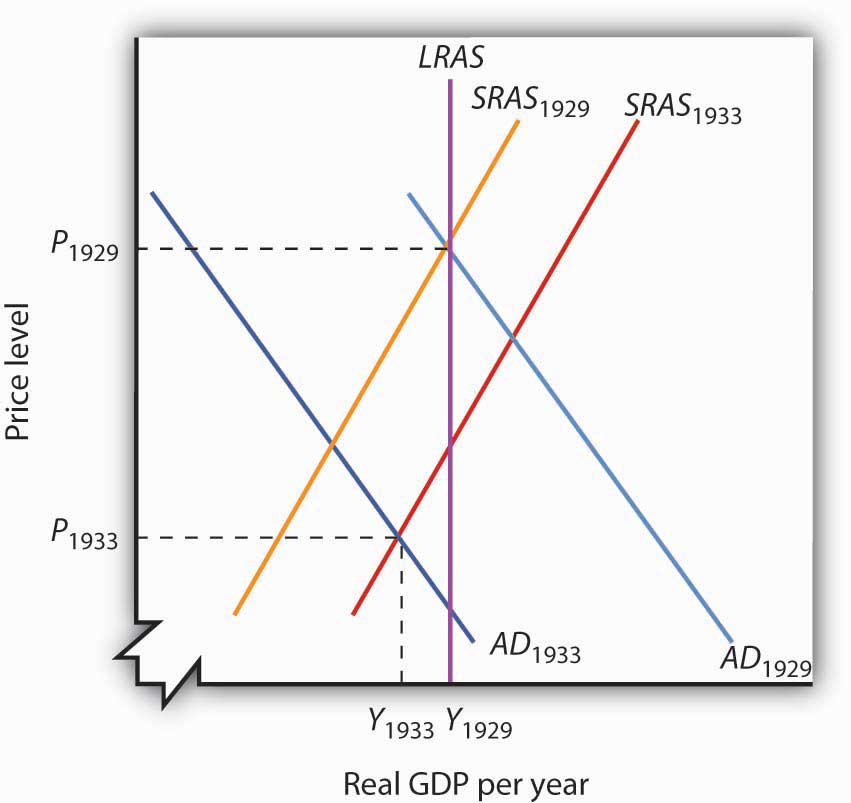

Answer to Try It! Problem

To the graph in the previous Try It! problem we add the long-run aggregate supply curve to show that, with output below potential, the U.S. economy in 1933 was in a recessionary gap. The unemployment rate was above the natural rate of unemployment. Indeed, real GDP in 1933 was about 30% below what it had been in 1929, and the unemployment rate had increased from 3% to 25%. Note that during the period of the Great Depression, wages did fall. The notion of nominal wage and other price stickiness discussed in this section should not be construed to mean complete wage and price inflexibility. Rather, during this period, nominal wages and other prices were not flexible enough to restore the economy to the potential level of output. There are two basic choices on how to close recessionary gaps. Nonintervention would mean waiting for wages to fall further. As wages fall, the short-run aggregate supply curve would continue to shift to the right. The alternative would be to use some type of expansionary policy. This would shift the aggregate demand curve to the right. These two options were illustrated in Figure 22.18 "Alternatives in Closing an Inflationary Gap".

Figure 22.21