This is “The Supply of Labor”, section 12.2 from the book Economics Principles (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

12.2 The Supply of Labor

Learning Objectives

- Explain the income and substitution effects of a wage change and how they affect the shape of the labor supply curve.

- Discuss the factors that can cause the supply curve for labor to shift.

The demand for labor is one determinant of the equilibrium wage and equilibrium quantity of labor in a perfectly competitive market. The supply of labor, of course, is the other.

Economists think of the supply of labor as a problem in which individuals weigh the opportunity cost of various activities that can fill an available amount of time and choose how to allocate it. Everyone has 24 hours in a day. There are lots of uses to which we can put our time: we can raise children, work, sleep, play, or participate in volunteer efforts. To simplify our analysis, let us assume that there are two ways in which an individual can spend his or her time: in work or in leisure. Leisure is a type of consumption good; individuals gain utility directly from it. Work provides income that, in turn, can be used to purchase goods and services that generate utility.

The more work a person does, the greater his or her income, but the smaller the amount of leisure time available. An individual who chooses more leisure time will earn less income than would otherwise be possible. There is thus a tradeoff between leisure and the income that can be earned from work. We can think of the supply of labor as the flip side of the demand for leisure. The more leisure people demand, the less labor they supply.

Two aspects of the demand for leisure play a key role in understanding the supply of labor. First, leisure is a normal good. All other things unchanged, an increase in income will increase the demand for leisure. Second, the opportunity cost or “price” of leisure is the wage an individual can earn. A worker who can earn $10 per hour gives up $10 in income by consuming an extra hour of leisure. The $10 wage is thus the price of an hour of leisure. A worker who can earn $20 an hour faces a higher price of leisure.

Income and Substitution Effects

Suppose wages rise. The higher wage increases the price of leisure. We saw in the chapter on consumer choice that consumers substitute more of other goods for a good whose price has risen. The substitution effect of a higher wage causes the consumer to substitute labor for leisure. To put it another way, the higher wage induces the individual to supply a greater quantity of labor.

We can see the logic of this substitution effect in terms of the marginal decision rule. Suppose an individual is considering a choice between extra leisure and the additional income from more work. Let MULe denote the marginal utility of an extra hour of leisure. What is the price of an extra hour of leisure? It is the wage W that the individual forgoes by not working for an hour. The extra utility of $1 worth of leisure is thus given by MULe/W.

Suppose, for example, that the marginal utility of an extra hour of leisure is 20 and the wage is $10 per hour. Then MULe/W equals 20/10, or 2. That means that the individual gains 2 units of utility by spending an additional $1 worth of time on leisure. For a person facing a wage of $10 per hour, $1 worth of leisure would be the equivalent of 6 minutes of leisure time.

Let MUY be the marginal utility of an additional $1 of income (Y is the abbreviation economists generally assign to income). The price of $1 of income is just $1, so the price of income PY is always $1. Utility is maximized by allocating time between work and leisure so that:

Equation 12.5

Now suppose the wage rises from W to W’. That reduces the marginal utility of $1 worth of leisure, MULe/W, so that the extra utility of earning $1 will now be greater than the extra utility of $1 worth of leisure:

Equation 12.6

Faced with the inequality in Equation 12.6, an individual will give up some leisure time and spend more time working. As the individual does so, however, the marginal utility of the remaining leisure time rises and the marginal utility of the income earned will fall. The individual will continue to make the substitution until the two sides of the equation are again equal. For a worker, the substitution effect of a wage increase always reduces the amount of leisure time consumed and increases the amount of time spent working. A higher wage thus produces a positive substitution effect on labor supply.

But the higher wage also has an income effect. An increased wage means a higher income, and since leisure is a normal good, the quantity of leisure demanded will go up. And that means a reduction in the quantity of labor supplied.

For labor supply problems, then, the substitution effect is always positive; a higher wage induces a greater quantity of labor supplied. But the income effect is always negative; a higher wage implies a higher income, and a higher income implies a greater demand for leisure, and more leisure means a lower quantity of labor supplied. With the substitution and income effects working in opposite directions, it is not clear whether a wage increase will increase or decrease the quantity of labor supplied—or leave it unchanged.

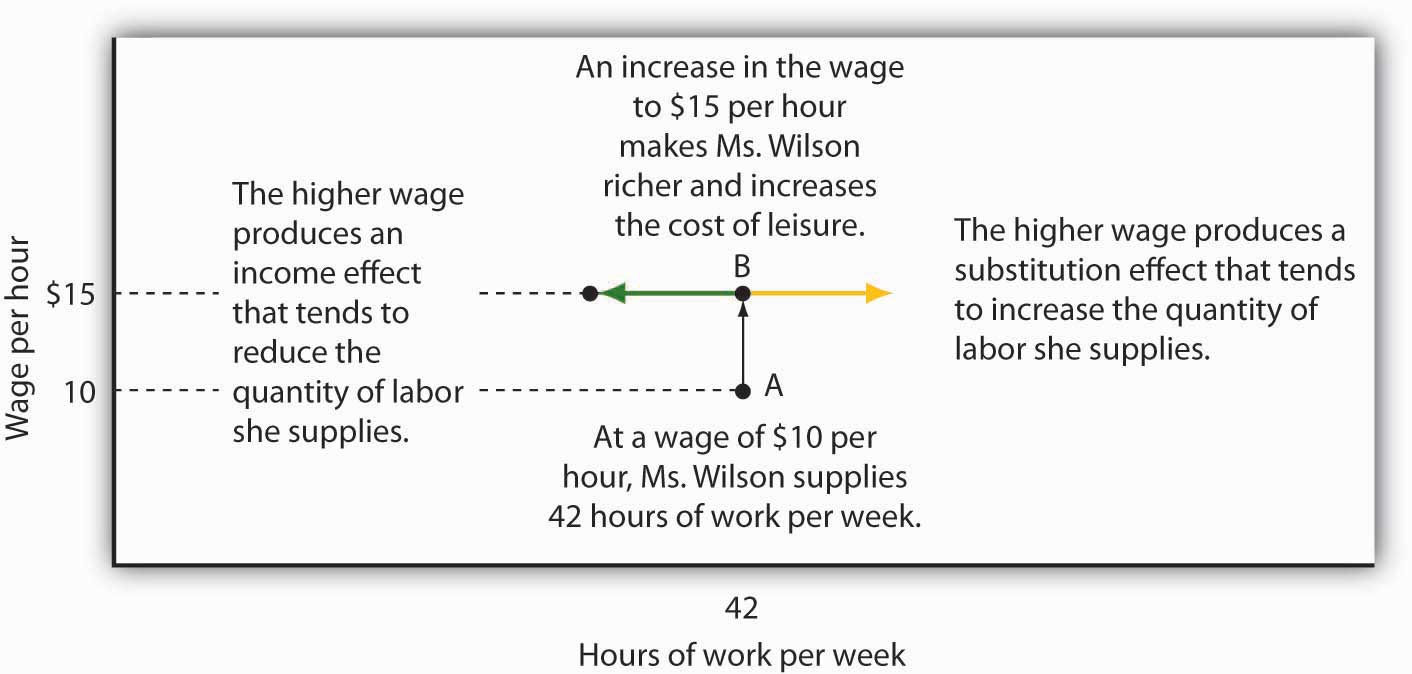

Figure 12.7 "The Substitution and Income Effects of a Wage Change" illustrates the opposite pull of the substitution and income effects of a wage change facing an individual worker. A janitor, Meredith Wilson, earns $10 per hour. She now works 42 hours per week, on average, earning $420.

Figure 12.7 The Substitution and Income Effects of a Wage Change

The substitution and income effects influence Meredith Wilson’s supply of labor when she gets a pay raise. At a wage of $10 per hour, she supplies 42 hours of work per week (point A). At $15 per hour, the substitution effect pulls in the direction of an increased quantity of labor supplied, and the income effect pulls in the opposite direction.

Now suppose Ms. Wilson receives a $5 raise to $15 per hour. As shown in Figure 12.7 "The Substitution and Income Effects of a Wage Change", the substitution effect of the wage change induces her to increase the quantity of labor she supplies; she substitutes some of her leisure time for additional hours of work. But she is richer now; she can afford more leisure. At a wage of $10 per hour, she was earning $420 per week. She could earn that same amount at the higher wage in just 28 hours. With her higher income, she can certainly afford more leisure time. The income effect of the wage change is thus negative; the quantity of labor supplied falls. The effect of the wage increase on the quantity of labor Ms. Wilson actually supplies depends on the relative strength of the substitution and income effects of the wage change. We will see what Ms. Wilson decides to do in the next section.

Wage Changes and the Slope of the Supply Curve

What would any one individual’s supply curve for labor look like? One possibility is that over some range of labor hours supplied, the substitution effect will dominate. Because the marginal utility of leisure is relatively low when little labor is supplied (that is, when most time is devoted to leisure), it takes only a small increase in wages to induce the individual to substitute more labor for less leisure. Further, because few hours are worked, the income effect of those wage changes will be small.

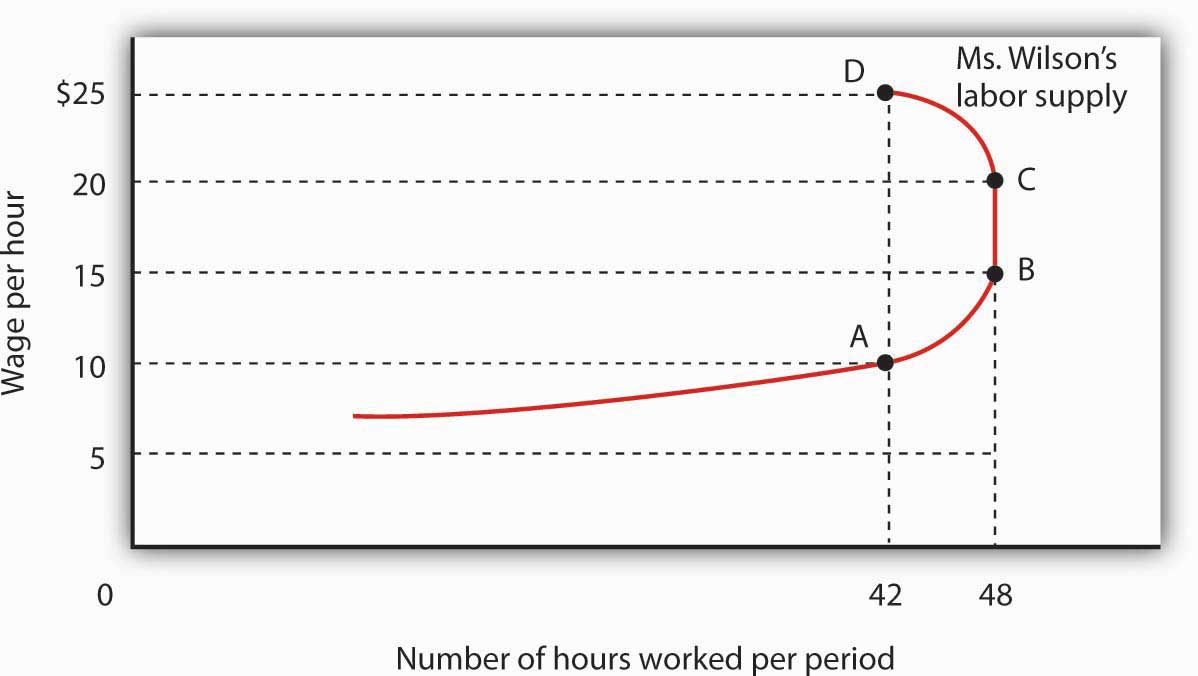

Figure 12.8 "A Backward-Bending Supply Curve for Labor" shows Meredith Wilson’s supply curve for labor. At a wage of $10 per hour, she supplies 42 hours of work per week (point A). An increase in her wage to $15 per hour boosts her quantity supplied to 48 hours per week (point B). The substitution effect thus dominates the income effect of a higher wage.

Figure 12.8 A Backward-Bending Supply Curve for Labor

As the wage rate increases from $10 to $15 per hour, the quantity of labor Meredith Wilson supplies increases from 42 to 48 hours per week. Between points A and B, the positive substitution effect of the wage increase outweighs the negative income effect. As the wage rises above $15, the negative income effect just offsets the substitution effect, and Ms. Wilson’s supply curve becomes a vertical line between points B and C. As the wage rises above $20, the income effect becomes stronger than the substitution effect, and the supply curve bends backward between points C and D.

It is possible that beyond some wage rate, the negative income effect of a wage increase could just offset the positive substitution effect; over that range, a higher wage would have no effect on the quantity of labor supplied. That possibility is illustrated between points B and C on the supply curve in Figure 12.8 "A Backward-Bending Supply Curve for Labor"; Ms. Wilson’s supply curve is vertical. As wages continue to rise, the income effect becomes even stronger, and additional increases in the wage reduce the quantity of labor she supplies. The supply curve illustrated here bends backward beyond point C and thus assumes a negative slope. The supply curve for labor can thus slope upward over part of its range, become vertical, and then bend backward as the income effect of higher wages begins to dominate the substitution effect.

It is quite likely that some individuals have backward-bending supply curves for labor—beyond some point, a higher wage induces those individuals to work less, not more. However, supply curves for labor in specific labor markets are generally upward sloping. As wages in one industry rise relative to wages in other industries, workers shift their labor to the relatively high-wage one. An increased quantity of labor is supplied in that industry. While some exceptions have been found, the mobility of labor between competitive labor markets is likely to prevent the total number of hours worked from falling as the wage rate increases. Thus we shall assume that supply curves for labor in particular markets are upward sloping.

Shifts in Labor Supply

What events shift the supply curve for labor? People supply labor in order to increase their utility—just as they demand goods and services in order to increase their utility. The supply curve for labor will shift in response to changes in the same set of factors that shift demand curves for goods and services.

Changes in Preferences

A change in attitudes toward work and leisure can shift the supply curve for labor. If people decide they value leisure more highly, they will work fewer hours at each wage, and the supply curve for labor will shift to the left. If they decide they want more goods and services, the supply curve is likely to shift to the right.

Changes in Income

An increase in income will increase the demand for leisure, reducing the supply of labor. We must be careful here to distinguish movements along the supply curve from shifts of the supply curve itself. An income change resulting from a change in wages is shown by a movement along the curve; it produces the income and substitution effects we already discussed. But suppose income is from some other source: a person marries and has access to a spouse’s income, or receives an inheritance, or wins a lottery. Those nonlabor increases in income are likely to reduce the supply of labor, thereby shifting the supply curve for labor of the recipients to the left.

Changes in the Prices of Related Goods and Services

Several goods and services are complements of labor. If the cost of child care (a complement to work effort) falls, for example, it becomes cheaper for workers to go to work, and the supply of labor tends to increase. If recreational activities (which are a substitute for work effort) become much cheaper, individuals might choose to consume more leisure time and supply less labor.

Changes in Population

An increase in population increases the supply of labor; a reduction lowers it. Labor organizations have generally opposed increases in immigration because their leaders fear that the increased number of workers will shift the supply curve for labor to the right and put downward pressure on wages.

Changes in Expectations

One change in expectations that could have an effect on labor supply is life expectancy. Another is confidence in the availability of Social Security. Suppose, for example, that people expect to live longer yet become less optimistic about their likely benefits from Social Security. That could induce an increase in labor supply.

Labor Supply in Specific Markets

The supply of labor in particular markets could be affected by changes in any of the variables we have already examined—changes in preferences, incomes, prices of related goods and services, population, and expectations. In addition to these variables that affect the supply of labor in general, there are changes that could affect supply in specific labor markets.

A change in wages in related occupations could affect supply in another. A sharp reduction in the wages of surgeons, for example, could induce more physicians to specialize in, say, family practice, increasing the supply of doctors in that field. Improved job opportunities for women in other fields appear to have decreased the supply of nurses, shifting the supply curve for nurses to the left.

The supply of labor in a particular market could also shift because of a change in entry requirements. Most states, for example, require barbers and beauticians to obtain training before entering the profession. Elimination of such requirements would increase the supply of these workers. Financial planners have, in recent years, sought the introduction of tougher licensing requirements, which would reduce the supply of financial planners.

Worker preferences regarding specific occupations can also affect labor supply. A reduction in willingness to take risks could lower the supply of labor available for risky occupations such as farm work (the most dangerous work in the United States), law enforcement, and fire fighting. An increased desire to work with children could raise the supply of child-care workers, elementary school teachers, and pediatricians.

Key Takeaways

- A higher wage increases the opportunity cost or price of leisure and increases worker incomes. The effects of these two changes pull the quantity of labor supplied in opposite directions.

- A wage increase raises the quantity of labor supplied through the substitution effect, but it reduces the quantity supplied through the income effect. Thus an individual’s supply curve of labor may be positively or negatively sloped, or have sections that are positively sloped, sections that are negatively sloped, and vertical sections. While some exceptions have been found, the labor supply curves for specific labor markets are generally upward sloping.

- The supply curve for labor will shift as a result of a change in worker preferences, a change in nonlabor income, a change in the prices of related goods and services, a change in population, or a change in expectations.

- In addition to the effects on labor supply of the variables just cited, other factors that can change the supply of labor in particular markets are changes in wages in related markets or changes in entry requirements.

Try It!

Economists Laura Duberstein and Karen Oppenheim Mason analyzed the labor-supply decisions of 1,383 mothers with preschool-aged children in the Detroit Metropolitan area.Laura Duberstein and Karen Oppenheim Mason, “Do Child Care Costs Influence Women’s Work Plans? Analysis for a Metropolitan Area,” Research Report, Population Studies Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, July 1991.

They found that respondents were more likely to work the higher the wage, less likely to work if they preferred a traditional family structure with a husband as the primary breadwinner, less likely to work if they felt that care provided by others was strongly inferior to a mother’s care, and less likely to work if child-care costs were higher. Given these findings, explain how each of the following would affect the labor supply of mothers with preschool-aged children.

- An increase in the wage

- An increase in the preference for a traditional family structure

- An increased sense that child care is inferior to a mother’s care

- An increase in the cost of child care

(Remember to distinguish between movements along the curve and shifts of the curve.) Is the labor supply curve positively or negatively sloped? Does the substitution effect or income effect dominate?

Case in Point: An Airline Pilot’s Lament

Figure 12.9

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Arguably, no single sector of the U.S. economy was hit harder by the events of 9/11 than the airline industry. By the time passengers did start returning, though, more than just the routine of getting through airport security had changed. Rather, the structure of the industry had begun to shift from domination by large national carriers—such as Delta, American, and United—operating according to the hub-and-spoke model, to increased competition from lower-cost regional carriers offering point-to-point service. Efforts by the large carriers in the early 2000s to reign in their costs and restore their financial health led to agreements with their labor unions that resulted in lower wages for most categories of airline workers.

How have airline employees responded to lower wages? Some categories of workers, such as mechanics, have little flexibility in deciding how many hours to work, but others, such as pilots, do. Below is an explanation by a female pilot who works for a major airline of the impact of wages cuts on her labor supply:

“We were normally scheduled for anywhere from 15 to 18 days a month, which translated into 80 to 95 hours of flying and around 280 hours of duty time. Duty time includes flight planning, preflighting, crew briefing, boarding, preflight checks of the airplane, etc. We bid for a monthly schedule that would fall somewhere in that range. After we were assigned our schedule for a month, we usually had the flexibility to drop or trade trips within certain constraints. Without going into the vast complexities of our contract, I can tell you that, in general, we were allowed to drop down to 10 days a month, provided the company could cover the trips we wanted to drop, and still be considered a full-time employee. Generally, at that time, my goal was to work a minimum of 10 to 12 days a month and a maximum of 15 days a month.

“After the first round of pay cuts, the typical month became 16 to 20 days of flying. With that round of pay cuts, my general goal became to work a minimum of 15 days a month and a maximum of 17 days a month. I imagine that with another round of cuts my goal would be to keep my pay as high as I possibly can.

“Basically, I have a target income in mind. Anything above that was great, but I chose to have more days at home rather than more pay. As my target income became more difficult to achieve, I chose to work more days and hours to keep close to my target income…When total compensation drops by more than 50% it is difficult to keep your financial head above water no matter how well you have budgeted.”

Source: personal interview.

Answer to Try It! Problem

The first question is about willingness to work as the wage rate changes. It thus refers to movement along the labor supply curve. That mothers of preschool-age children are more willing to work the higher the wage implies an upward-sloping labor supply curve. When the labor supply curve is upward sloping, the substitution effect dominates the income effect. The other three questions refer to factors that cause the labor supply curve to shift. In all three cases, the circumstances imply that the labor supply curve would shift to the left.