This is “Media and Culture”, chapter 1 from the book Culture and Media (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Media and Culture

Pop Culture Mania

Figure 1.1

Source: Used with permission from Getty Images.

In 1850, an epidemic swept America—but instead of leaving victims sick with fever or flu, this epidemic involved a rabid craze for the music of Swedish soprano Jenny Lind. American showman P. T. Barnum (who would later go on to found the circus now known as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey), a shrewd marketer and self-made millionaire, is credited with spreading “Lindomania” through a series of astute show-business moves. Barnum promised Lind an unprecedented $1,000-a-night fee (the equivalent of $28,300 in 2009) for her entire 93-performance tour of the United States. Ever the savvy self-promoter, Barnum turned his huge investment to his advantage by using it to create publicity—and it paid off. When the Swedish soprano’s ship docked on U.S. shores, she was greeted by 40,000 ardent fans; another 20,000 swarmed her hotel.“P. T. Barnum,” Answers.com, http://www.answers.com/topic/p-t-barnum. Congress was adjourned specifically for Lind’s visit to Washington, DC, where the National Theatre had to be enlarged to accommodate her audiences. A town in California and an island in Canada were named in her honor. Enthusiasts could purchase Jenny Lind hats, chairs, boots, opera glasses, and even pianos. Barnum’s marketing expertise made Lind a household name and created an overwhelming demand for a singer previously unknown to American audiences.

The “Jenny rage” that the savvy Barnum was able to create was not a unique phenomenon, however; a little more than a century later, a new craze transformed some American teenagers into screaming, fainting Beatlemaniacs. Though other performers like Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley were no strangers to manic crowds, the Beatles attracted an unprecedented amount of attention when they first arrived in the United States. When the British foursome touched down at New York’s Kennedy Airport in 1964, they were met by more than 3,000 frenzied fans. Their performance on The Ed Sullivan Show was seen by 73 million people, or 40 percent of the U.S. population. The crime rate that night dropped to its lowest level in 50 years.Barbara Ehrenreich, Elizabeth Hess, and Gloria Jacobs, “Beatlemania: Girls Just Want to Have Fun,” in The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, ed. Lisa A. Lewis (New York: Routledge, 1992), 84–106. Beatlemania was at such a fever pitch that Life magazine cautioned that “a Beatle who ventures out unguarded into the streets runs the very real peril of being dismembered or crushed to death by his fans.”Ibid. The BBC publicized the trend and perhaps added to it by highlighting the paraphernalia for fans to spend their money on: “T-shirts, sweat shirts, turtle-neck sweaters, tight-legged trousers, night shirts, scarves, and jewelry inspired by the Beatles” were all available, as were Beatles-style mop-top wigs.Ibid.

In the 21st century, rabid fans could turn their attention to a whole swath of pop stars in the making when the reality TV program American Idol hit the airwaves in 2002. The show was the only television program ever to have snagged the top spot in the Nielsen ratings for six seasons in a row, often averaging more than 30 million nightly viewers. Rival television network executives were alarmed, deeming the pop giant “the ultimate schoolyard bully,” “the Death Star,” or even “the most impactful show in the history of television,” according to former NBC Universal CEO Jeff Zucker.Bill Carter, “For Fox’s Rivals, ‘American Idol’ Remains a ‘Schoolyard Bully,’” New York Times, February 20, 2007, Arts section. New cell phone technologies allowed viewers to have a direct role in the program’s star-making enterprise through casting votes, signing up for text alerts, or playing trivia games on their phones. In 2009, AT&T estimated that Idol-related text traffic amounted to 178 million messages.James Poniewozik, “American Idol’s Voting Scandal (Or Not),” Tuned In (blog), Time, May 28, 2009, http://tunedin.blogs.time.com/2009/05/28/american-idols-voting-scandal-or-not/.

These three crazes all relied on various forms of media to create excitement. Whether through newspaper advertisements, live television broadcasts, or integrated Internet marketing, media industry tastemakers help shape what we care about. For as long as mass media has existed in the United States, it’s helped to create and fuel mass crazes, skyrocketing celebrities, and pop culture manias of all kinds. Even in our era of seemingly limitless entertainment options, mass hits like American Idol still have the ability to dominate the public’s attention. In the chapters to come, we’ll look at different kinds of mass media and how they have been changed by—and are changing—the world we live in.

1.1 Intersection of American Media and Culture

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between mass communication and mass media.

- Identify key points in American media and culture.

Pop culture and American media are inextricably linked. Consider that Jenny Lind, the Beatles, and American Idol were each promoted using a then-new technology (photography for Lind, television for the Beatles, and the Internet and text messaging for American Idol).

Mass Communication, Mass Media, and Culture

The chapters to come will provide an in-depth look at many kinds of media, at how media trends are reshaping the United States’ cultural landscape, and at how that culture shapes media in turn. These topics will be explored through an examination of mass media and mass communication both past and present—and speculation about what the future might look like.

First, it is important to distinguish between mass communication and mass media and to attempt a working definition of culture. Mass communicationInformation transmitted to large segments of the population. refers to information transmitted to large segments of the population. The transmission of mass communication may happen using one or many different kinds of mediaA means of transmission; can be print, digital, or electronic. (singular medium), which is the means of transmission, whether print, digital, or electronic. Mass mediaA means of communication that is designed to reach a wide audience. Some forms are radio, newspapers, magazines, books, video games, and Internet media such as blogs, podcasts, and video sharing. specifically refers to a means of communication that is designed to reach a wide audience. Mass media platforms are commonly considered to include radio, newspapers, magazines, books, video games, and Internet media such as blogs, podcasts, and video sharing. Another way to consider the distinction is that a mass media message may be disseminated through several forms of mass media, such as an ad campaign with television, radio, and Internet components. CultureThe shared values, attitudes, beliefs, and practices that characterize a social group, organization, or institution. generally refers to the shared values, attitudes, beliefs, and practices that characterize a social group, organization, or institution. Just as it is difficult to pin down an exact definition of culture, cultures themselves can be hard to draw boundaries around, as they are fluid, diverse, and often overlapping.

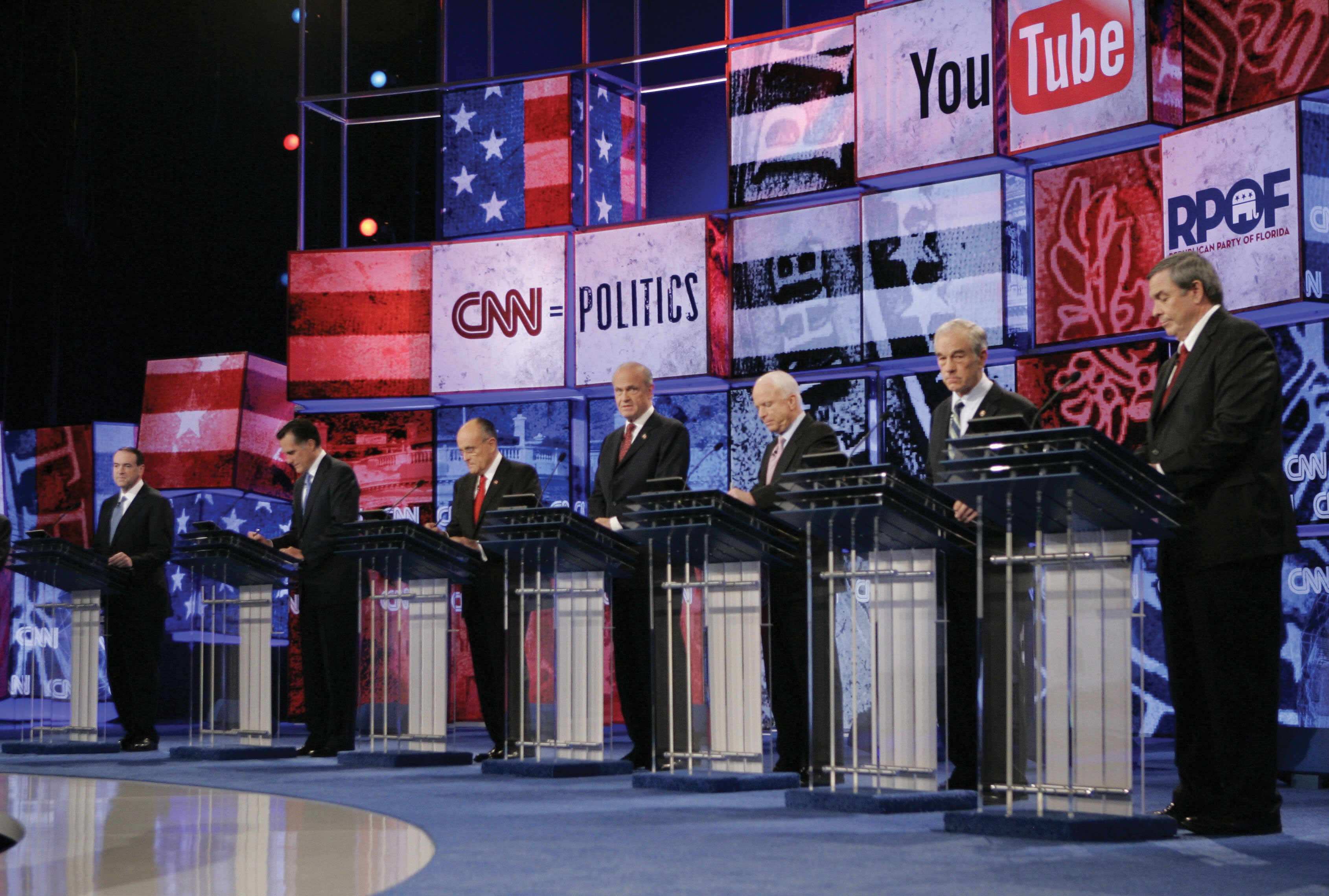

Figure 1.2

Advances in media technology allowed for unprecedented voter participation in the 2007 CNN/YouTube® presidential debates.

Source: Used with permission from Getty Images.

Throughout U.S. history, evolving media technologies have changed the way we relate socially, economically, and politically. In 2007, for example, a joint venture between the 24-hour news network CNN and the video-sharing site YouTube allowed voters to pose questions directly to presidential candidates in two televised debates. Voters could record their questions and upload them to YouTube, and a selection of these videos were then chosen by the debate moderators and played directly to the presidential candidates. This new format opened up the presidential debates to a much wider array of people, allowing for greater voter participation than has been possible in the past, where questions were posed solely by journalists or a few carefully chosen audience members.

In today’s wired world of smartphones and streaming satellite feeds, our expectations of our leaders, celebrities, teachers, and even ourselves are changing in even more drastic ways. This book provides you with the context, tools, and theories to engage with the world of mass media through an examination of the history, theory, and effects of media practices and roles in America. This book also provides you with the framework to consider some of the crucial issues affecting media and culture in today’s world.

Key Takeaways

- Mass communication refers to a message transmitted to a large audience; the means of transmission is known as mass media. Many different kinds of mass media exist and have existed for centuries. Both the messages and the media affect culture, which is a diffused collection of behaviors, practices, beliefs, and values that are particular to a group, organization, or institution. Culture and media exert influence on each other in subtle, complex ways.

- The 2008 election is an example of how changes in media technology have had a major impact on society. But the influence goes both ways, and sometimes cultural changes impact how media evolves.

Exercises

Read the following questions about media and culture:

- The second half of the 20th century included a huge increase in forms of media available, including radio, cinema, television, and the Internet. But some form of mass communication has always been a part of U.S. history. What were the dominant forms of media present in the United States during the Industrial Revolution? World Wars I and II? Other important historical eras? How did these forms of media differ from the ones we have today? How did they help shape the way people interacted with and understood the world they lived in? How does mass communication differ from mass media?

- Contemporary Americans have more means of getting information and entertainment than ever before. What are the major media present in the United States today? How do these forms of media interact with one another? How do they overlap? How are they distinct?

-

What is the role of media in American culture today?

- Some people argue that high-profile cases in the 1990s, such as the criminal trial of O. J. Simpson, Bill Clinton’s impeachment proceedings, and the first Persian Gulf War helped fuel the demand for 24-hour news access. What are some other ways that culture affects media?

- Conversely, how does mass media affect culture? Do violent television shows and video games influence viewers to become more violent? Is the Internet making our culture more open and democratic or more shallow and distracted?

- Though we may not have hover cars and teleportation, today’s electronic gadgets would probably leave Americans of a century ago breathless. How can today’s media landscape help us understand what might await us in years to come? What will the future of American media and culture look like?

- Write down some of your initial responses or reactions, based on your prior knowledge or intuition. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph. Keep the piece of paper somewhere secure and return to it on the last day of the course. Were your responses on target? How has your understanding of media and culture changed? How might you answer questions differently now?

1.2 The Evolution of Media

Learning Objectives

- Identify four roles the media performs in our society.

- Recognize events that affected the adoption of mass media.

- Explain how different technological transitions have shaped media industries.

In 2010, Americans could turn on their television and find 24-hour news channels as well as music videos, nature documentaries, and reality shows about everything from hoarders to fashion models. That’s not to mention movies available on demand from cable providers or television and video available online for streaming or downloading. Half of U.S. households receive a daily newspaper, and the average person holds 1.9 magazine subscriptions.Project for Excellence in Journalism, The State of the News Media 2004, http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2004/.Jim Bilton, “The Loyalty Challenge: How Magazine Subscriptions Work,” In Circulation, January/February 2007. A University of California, San Diego study claimed that U.S. households consumed a total of approximately 3.6 zettabytes of information in 2008—the digital equivalent of a 7-foot high stack of books covering the entire United States—a 350 percent increase since 1980.Doug Ramsey, “UC San Diego Experts Calculate How Much Information Americans Consume” UC San Diego News Center, December 9, 2009, http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/newsrel/general/12-09Information.asp. Americans are exposed to media in taxicabs and buses, in classrooms and doctors’ offices, on highways, and in airplanes. We can begin to orient ourselves in the information cloud through parsing what roles the media fills in society, examining its history in society, and looking at the way technological innovations have helped bring us to where we are today.

What Does Media Do for Us?

Media fulfills several basic roles in our society. One obvious role is entertainment. Media can act as a springboard for our imaginations, a source of fantasy, and an outlet for escapism. In the 19th century, Victorian readers disillusioned by the grimness of the Industrial Revolution found themselves drawn into fantastic worlds of fairies and other fictitious beings. In the first decade of the 21st century, American television viewers could peek in on a conflicted Texas high school football team in Friday Night Lights; the violence-plagued drug trade in Baltimore in The Wire; a 1960s-Manhattan ad agency in Mad Men; or the last surviving band of humans in a distant, miserable future in Battlestar Galactica. Through bringing us stories of all kinds, media has the power to take us away from ourselves.

Media can also provide information and education. Information can come in many forms, and it may sometimes be difficult to separate from entertainment. Today, newspapers and news-oriented television and radio programs make available stories from across the globe, allowing readers or viewers in London to access voices and videos from Baghdad, Tokyo, or Buenos Aires. Books and magazines provide a more in-depth look at a wide range of subjects. The free online encyclopedia Wikipedia has articles on topics from presidential nicknames to child prodigies to tongue twisters in various languages. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has posted free lecture notes, exams, and audio and video recordings of classes on its OpenCourseWare website, allowing anyone with an Internet connection access to world-class professors.

Another useful aspect of media is its ability to act as a public forumA social space that is open to all and that serves as a place for discussion of important issues. A public forum is not always a physical space; for example, a newspaper can be considered a public forum. for the discussion of important issues. In newspapers or other periodicals, letters to the editor allow readers to respond to journalists or to voice their opinions on the issues of the day. These letters were an important part of U.S. newspapers even when the nation was a British colony, and they have served as a means of public discourse ever since. The Internet is a fundamentally democratic medium that allows everyone who can get online the ability to express their opinions through, for example, blogging or podcasting—though whether anyone will hear is another question.

Similarly, media can be used to monitor government, business, and other institutions. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle exposed the miserable conditions in the turn-of-the-century meatpacking industry; and in the early 1970s, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered evidence of the Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up, which eventually led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. But purveyors of mass media may be beholden to particular agendas because of political slant, advertising funds, or ideological bias, thus constraining their ability to act as a watchdog. The following are some of these agendas:

- Entertaining and providing an outlet for the imagination

- Educating and informing

- Serving as a public forum for the discussion of important issues

- Acting as a watchdog for government, business, and other institutions

It’s important to remember, though, that not all media are created equal. While some forms of mass communication are better suited to entertainment, others make more sense as a venue for spreading information. In terms of print media, books are durable and able to contain lots of information, but are relatively slow and expensive to produce; in contrast, newspapers are comparatively cheaper and quicker to create, making them a better medium for the quick turnover of daily news. Television provides vastly more visual information than radio and is more dynamic than a static printed page; it can also be used to broadcast live events to a nationwide audience, as in the annual State of the Union address given by the U.S. president. However, it is also a one-way medium—that is, it allows for very little direct person-to-person communication. In contrast, the Internet encourages public discussion of issues and allows nearly everyone who wants a voice to have one. However, the Internet is also largely unmoderated. Users may have to wade through thousands of inane comments or misinformed amateur opinions to find quality information.

The 1960s media theorist Marshall McLuhan took these ideas one step further, famously coining the phrase “the medium is the messageA phrase coined by media theorist Marshall McLuhan asserting that every medium delivers information in a different way and that content is fundamentally shaped by the medium of transmission..”Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964). By this, McLuhan meant that every medium delivers information in a different way and that content is fundamentally shaped by the medium of transmission. For example, although television news has the advantage of offering video and live coverage, making a story come alive more vividly, it is also a faster-paced medium. That means more stories get covered in less depth. A story told on television will probably be flashier, less in-depth, and with less context than the same story covered in a monthly magazine; therefore, people who get the majority of their news from television may have a particular view of the world shaped not by the content of what they watch but its medium. Or, as computer scientist Alan Kay put it, “Each medium has a special way of representing ideas that emphasize particular ways of thinking and de-emphasize others.”Alan Kay, “The Infobahn Is Not the Answer,” Wired, May 1994. Kay was writing in 1994, when the Internet was just transitioning from an academic research network to an open public system. A decade and a half later, with the Internet firmly ensconced in our daily lives, McLuhan’s intellectual descendants are the media analysts who claim that the Internet is making us better at associative thinking, or more democratic, or shallower. But McLuhan’s claims don’t leave much space for individual autonomy or resistance. In an essay about television’s effects on contemporary fiction, writer David Foster Wallace scoffed at the “reactionaries who regard TV as some malignancy visited on an innocent populace, sapping IQs and compromising SAT scores while we all sit there on ever fatter bottoms with little mesmerized spirals revolving in our eyes…. Treating television as evil is just as reductive and silly as treating it like a toaster with pictures.”David Foster Wallace, “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again (New York: Little Brown, 1997). Nonetheless, media messages and technologies affect us in countless ways, some of which probably won’t be sorted out until long in the future.

A Brief History of Mass Media and Culture

Until Johannes Gutenberg’s 15th-century invention of the movable type printing press, books were painstakingly handwritten and no two copies were exactly the same. The printing press made the mass production of print media possible. Not only was it much cheaper to produce written material, but new transportation technologies also made it easier for texts to reach a wide audience. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Gutenberg’s invention, which helped usher in massive cultural movements like the European Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. In 1810, another German printer, Friedrich Koenig, pushed media production even further when he essentially hooked the steam engine up to a printing press, enabling the industrialization of printed media. In 1800, a hand-operated printing press could produce about 480 pages per hour; Koenig’s machine more than doubled this rate. (By the 1930s, many printing presses could publish 3,000 pages an hour.)

This increased efficiency went hand in hand with the rise of the daily newspaper. The newspaper was the perfect medium for the increasingly urbanized Americans of the 19th century, who could no longer get their local news merely through gossip and word of mouth. These Americans were living in unfamiliar territory, and newspapers and other media helped them negotiate the rapidly changing world. The Industrial Revolution meant that some people had more leisure time and more money, and media helped them figure out how to spend both. Media theorist Benedict Anderson has argued that newspapers also helped forge a sense of national identity by treating readers across the country as part of one unified community.Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, (London: Verso, 1991).

In the 1830s, the major daily newspapers faced a new threat from the rise of penny papers, which were low-priced broadsheets that served as a cheaper, more sensational daily news source. They favored news of murder and adventure over the dry political news of the day. While newspapers catered to a wealthier, more educated audience, the penny press attempted to reach a wide swath of readers through cheap prices and entertaining (often scandalous) stories. The penny press can be seen as the forerunner to today’s gossip-hungry tabloids.

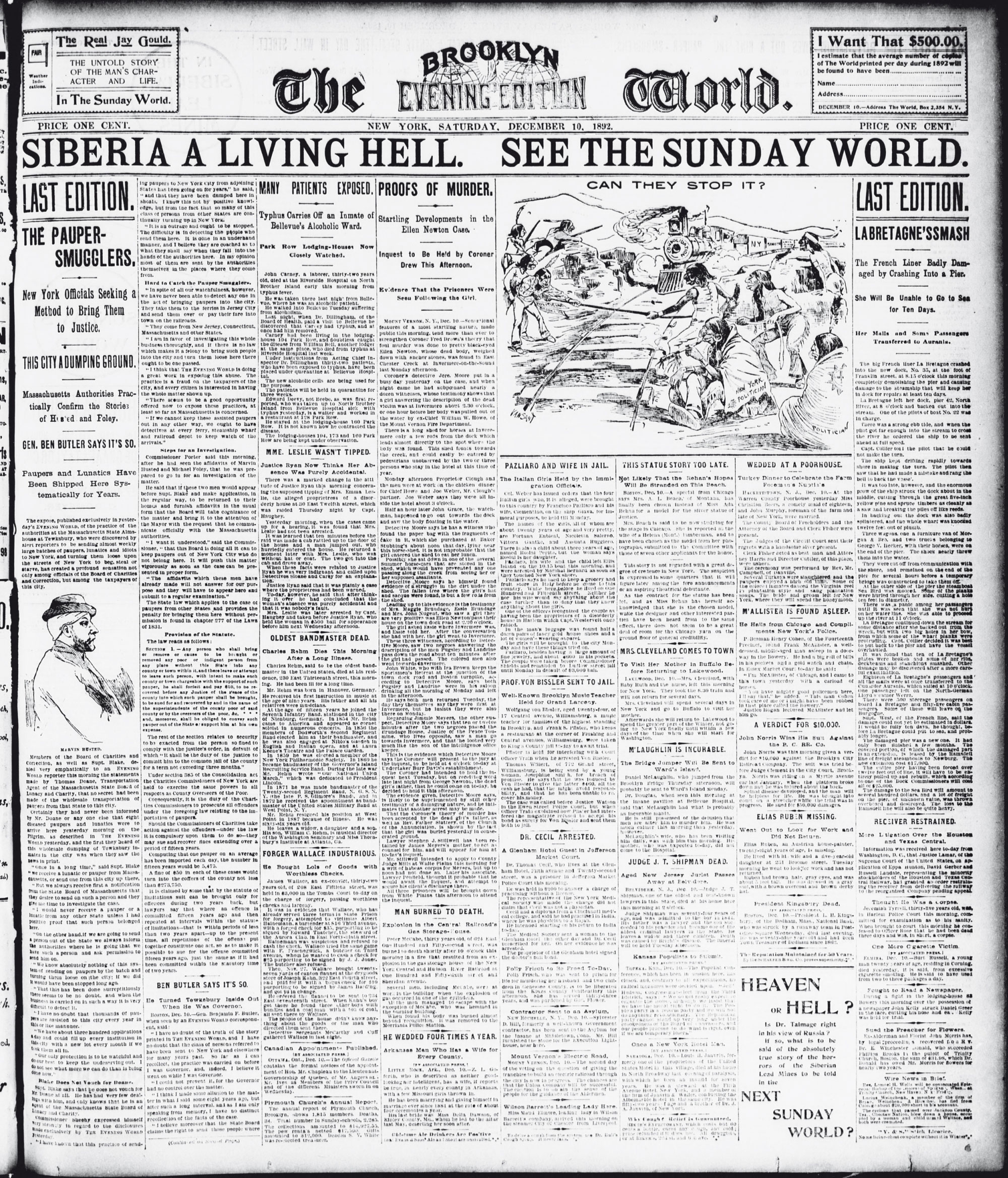

Figure 1.3

The penny press appealed to readers’ desires for lurid tales of murder and scandal.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the first major nonprint form of mass media—radio—exploded in popularity. Radios, which were less expensive than telephones and widely available by the 1920s, had the unprecedented ability of allowing huge numbers of people to listen to the same event at the same time. In 1924, Calvin Coolidge’s preelection speech reached more than 20 million people. Radio was a boon for advertisers, who now had access to a large and captive audience. An early advertising consultant claimed that the early days of radio were “a glorious opportunity for the advertising man to spread his sales propaganda” because of “a countless audience, sympathetic, pleasure seeking, enthusiastic, curious, interested, approachable in the privacy of their homes.”Asa Briggs and Peter Burke, A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2005). The reach of radio also meant that the medium was able to downplay regional differences and encourage a unified sense of the American lifestyle—a lifestyle that was increasingly driven and defined by consumer purchases. “Americans in the 1920s were the first to wear ready-made, exact-size clothing…to play electric phonographs, to use electric vacuum cleaners, to listen to commercial radio broadcasts, and to drink fresh orange juice year round.”Steven Mintz, “The Jazz Age: The American 1920s: The Formation of Modern American Mass Culture,” Digital History, 2007, http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?hhid=454. This boom in consumerism put its stamp on the 1920s and also helped contribute to the Great Depression of the 1930s.Library of Congress, “Radio: A Consumer Product and a Producer of Consumption,” Coolidge-Consumerism Collection, http://lcweb2.loc.gov:8081/ammem/amrlhtml/inradio.html. The consumerist impulse drove production to unprecedented levels, but when the Depression began and consumer demand dropped dramatically, the surplus of production helped further deepen the economic crisis, as more goods were being produced than could be sold.

The post–World War II era in the United States was marked by prosperity, and by the introduction of a seductive new form of mass communication: television. In 1946, about 17,000 televisions existed in the United States; within 7 years, two-thirds of American households owned at least one set. As the United States’ gross national product (GNP) doubled in the 1950s, and again in the 1960s, the American home became firmly ensconced as a consumer unit; along with a television, the typical U.S. household owned a car and a house in the suburbs, all of which contributed to the nation’s thriving consumer-based economy.Briggs and Burke, Social History of the Media. Broadcast television was the dominant form of mass media, and the three major networks controlled more than 90 percent of the news programs, live events, and sitcoms viewed by Americans. Some social critics argued that television was fostering a homogenous, conformist culture by reinforcing ideas about what “normal” American life looked like. But television also contributed to the counterculture of the 1960s. The Vietnam War was the nation’s first televised military conflict, and nightly images of war footage and war protesters helped intensify the nation’s internal conflicts.

Broadcast technology, including radio and television, had such a hold on the American imagination that newspapers and other print media found themselves having to adapt to the new media landscape. Print media was more durable and easily archived, and it allowed users more flexibility in terms of time—once a person had purchased a magazine, he or she could read it whenever and wherever. Broadcast media, in contrast, usually aired programs on a fixed schedule, which allowed it to both provide a sense of immediacy and fleetingness. Until the advent of digital video recorders in the late 1990s, it was impossible to pause and rewind a live television broadcast.

The media world faced drastic changes once again in the 1980s and 1990s with the spread of cable television. During the early decades of television, viewers had a limited number of channels to choose from—one reason for the charges of homogeneity. In 1975, the three major networks accounted for 93 percent of all television viewing. By 2004, however, this share had dropped to 28.4 percent of total viewing, thanks to the spread of cable television. Cable providers allowed viewers a wide menu of choices, including channels specifically tailored to people who wanted to watch only golf, classic films, sermons, or videos of sharks. Still, until the mid-1990s, television was dominated by the three large networks. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, an attempt to foster competition by deregulating the industry, actually resulted in many mergers and buyouts that left most of the control of the broadcast spectrum in the hands of a few large corporations. In 2003, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) loosened regulation even further, allowing a single company to own 45 percent of a single market (up from 25 percent in 1982).Ibid.

Technological Transitions Shape Media Industries

New media technologies both spring from and cause social changes. For this reason, it can be difficult to neatly sort the evolution of media into clear causes and effects. Did radio fuel the consumerist boom of the 1920s, or did the radio become wildly popular because it appealed to a society that was already exploring consumerist tendencies? Probably a little bit of both. Technological innovations such as the steam engine, electricity, wireless communication, and the Internet have all had lasting and significant effects on American culture. As media historians Asa Briggs and Peter Burke note, every crucial invention came with “a change in historical perspectives.”Ibid. Electricity altered the way people thought about time because work and play were no longer dependent on the daily rhythms of sunrise and sunset; wireless communication collapsed distance; the Internet revolutionized the way we store and retrieve information.

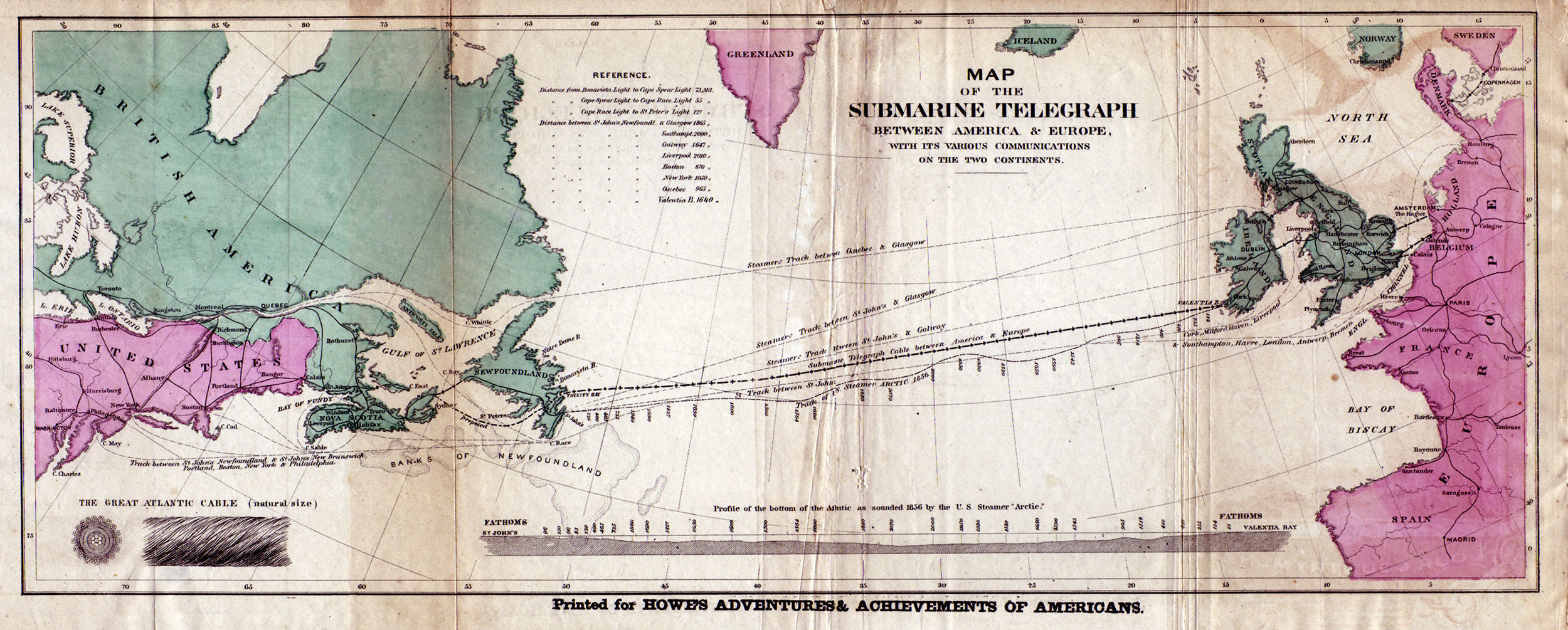

Figure 1.4

The transatlantic telegraph cable made nearly instantaneous communication between the United States and Europe possible for the first time in 1858.

The contemporary media age can trace its origins back to the electrical telegraph, patented in the United States by Samuel Morse in 1837. Thanks to the telegraph, communication was no longer linked to the physical transportation of messages; it didn’t matter whether a message needed to travel 5 or 500 miles. Suddenly, information from distant places was nearly as accessible as local news, as telegraph lines began to stretch across the globe, making their own kind of World Wide Web. In this way, the telegraph acted as the precursor to much of the technology that followed, including the telephone, radio, television, and Internet. When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, allowing nearly instantaneous communication from the United States to Europe, the London Times described it as “the greatest discovery since that of Columbus, a vast enlargement…given to the sphere of human activity.”Ibid.

Not long afterward, wireless communication (which eventually led to the development of radio, television, and other broadcast media) emerged as an extension of telegraph technology. Although many 19th-century inventors, including Nikola Tesla, were involved in early wireless experiments, it was Italian-born Guglielmo Marconi who is recognized as the developer of the first practical wireless radio system. Many people were fascinated by this new invention. Early radio was used for military communication, but soon the technology entered the home. The burgeoning interest in radio inspired hundreds of applications for broadcasting licenses from newspapers and other news outlets, retail stores, schools, and even cities. In the 1920s, large media networks—including the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS)—were launched, and they soon began to dominate the airwaves. In 1926, they owned 6.4 percent of U.S. broadcasting stations; by 1931, that number had risen to 30 percent.Ibid.

Figure 1.5

Gone With the Wind defeated The Wizard of Oz to become the first color film ever to win the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1939.

Source: Used with permission from Getty Images.

Source: Used with permission from Getty Images.

In addition to the breakthroughs in audio broadcasting, inventors in the 1800s made significant advances in visual media. The 19th-century development of photographic technologies would lead to the later innovations of cinema and television. As with wireless technology, several inventors independently created a form of photography at the same time, among them the French inventors Joseph Niépce and Louis Daguerre and the British scientist William Henry Fox Talbot. In the United States, George Eastman developed the Kodak camera in 1888, anticipating that Americans would welcome an inexpensive, easy-to-use camera into their homes as they had with the radio and telephone. Moving pictures were first seen around the turn of the century, with the first U.S. projection-hall opening in Pittsburgh in 1905. By the 1920s, Hollywood had already created its first stars, most notably Charlie Chaplin; by the end of the 1930s, Americans were watching color films with full sound, including Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz.

Television—which consists of an image being converted to electrical impulses, transmitted through wires or radio waves, and then reconverted into images—existed before World War II, but gained mainstream popularity in the 1950s. In 1947, there were 178,000 television sets made in the United States; 5 years later, 15 million were made. Radio, cinema, and live theater declined because the new medium allowed viewers to be entertained with sound and moving pictures in their homes. In the United States, competing commercial stations (including the radio powerhouses of CBS and NBC) meant that commercial-driven programming dominated. In Great Britain, the government managed broadcasting through the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Funding was driven by licensing fees instead of advertisements. In contrast to the U.S. system, the BBC strictly regulated the length and character of commercials that could be aired. However, U.S. television (and its increasingly powerful networks) still dominated. By the beginning of 1955, there were around 36 million television sets in the United States, but only 4.8 million in all of Europe. Important national events, broadcast live for the first time, were an impetus for consumers to buy sets so they could witness the spectacle; both England and Japan saw a boom in sales before important royal weddings in the 1950s.Ibid.

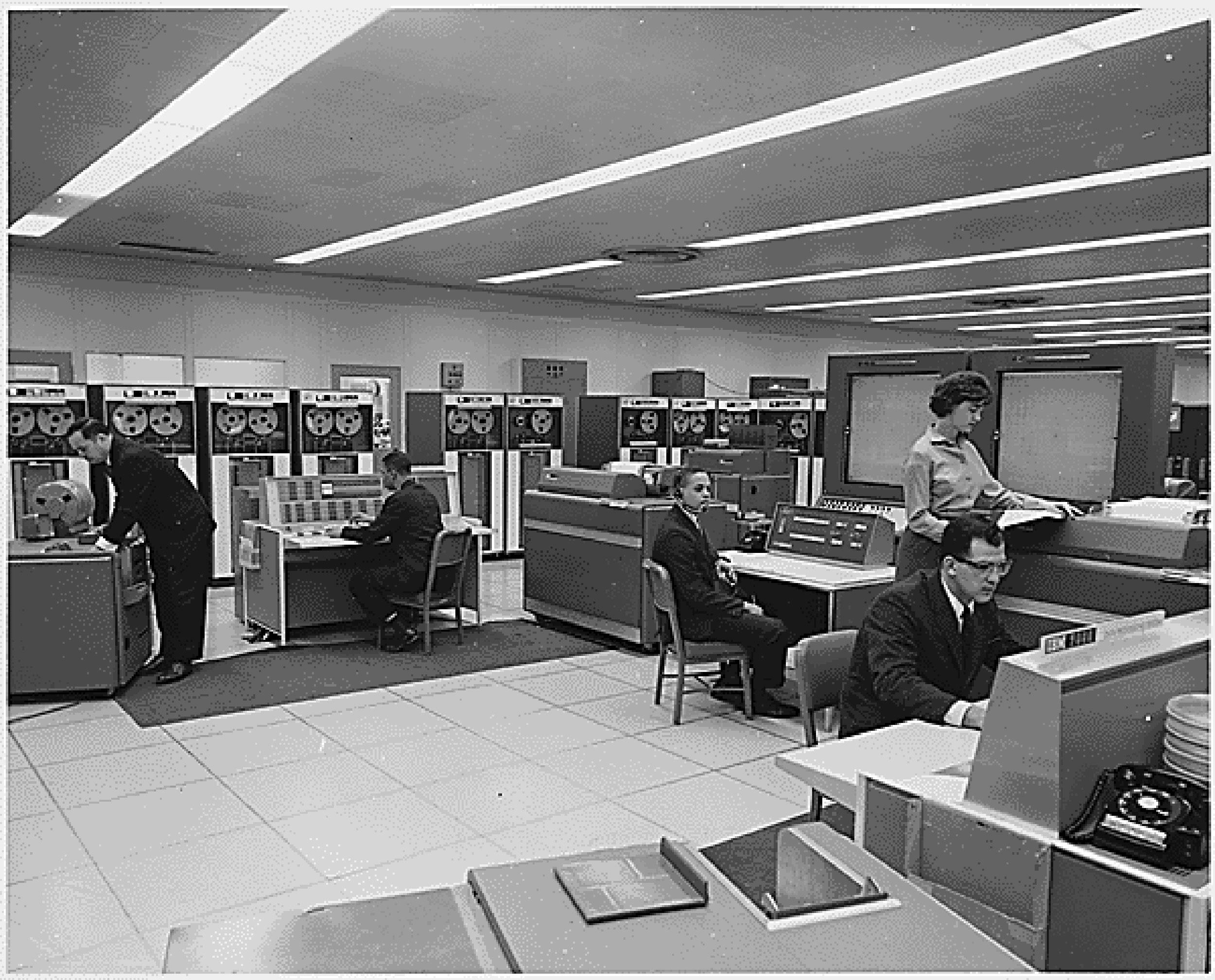

Figure 1.6

In the 1960s, the concept of a useful portable computer was still a dream; huge mainframes were required to run a basic operating system.

In 1969, management consultant Peter Drucker predicted that the next major technological innovation would be an electronic appliance that would revolutionize the way people lived just as thoroughly as Thomas Edison’s light bulb had. This appliance would sell for less than a television set and be “capable of being plugged in wherever there is electricity and giving immediate access to all the information needed for school work from first grade through college.”Ibid. Although Drucker may have underestimated the cost of this hypothetical machine, he was prescient about the effect these machines—personal computers—and the Internet would have on education, social relationships, and the culture at large. The inventions of random access memory (RAM) chips and microprocessors in the 1970s were important steps to the Internet age. As Briggs and Burke note, these advances meant that “hundreds of thousands of components could be carried on a microprocessor.”Ibid. The reduction of many different kinds of content to digitally stored information meant that “print, film, recording, radio and television and all forms of telecommunications [were] now being thought of increasingly as part of one complex.”Ibid. This process, also known as convergence, is a force that’s affecting media today.

Key Takeaways

-

Media fulfills several roles in society, including the following:

- entertaining and providing an outlet for the imagination,

- educating and informing,

- serving as a public forum for the discussion of important issues, and

- acting as a watchdog for government, business, and other institutions.

- Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press enabled the mass production of media, which was then industrialized by Friedrich Koenig in the early 1800s. These innovations led to the daily newspaper, which united the urbanized, industrialized populations of the 19th century.

- In the 20th century, radio allowed advertisers to reach a mass audience and helped spur the consumerism of the 1920s—and the Great Depression of the 1930s. After World War II, television boomed in the United States and abroad, though its concentration in the hands of three major networks led to accusations of homogenization. The spread of cable and subsequent deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s led to more channels, but not necessarily to more diverse ownership.

- Transitions from one technology to another have greatly affected the media industry, although it is difficult to say whether technology caused a cultural shift or resulted from it. The ability to make technology small and affordable enough to fit into the home is an important aspect of the popularization of new technologies.

Exercises

Choose two different types of mass communication—radio shows, television broadcasts, Internet sites, newspaper advertisements, and so on—from two different kinds of media. Make a list of what role(s) each one fills, keeping in mind that much of what we see, hear, or read in the mass media has more than one aspect. Then, answer the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- To which of the four roles media plays in society do your selections correspond? Why did the creators of these particular messages present them in these particular ways and in these particular mediums?

- What events have shaped the adoption of the two kinds of media you selected?

- How have technological transitions shaped the industries involved in the two kinds of media you have selected?

1.3 Convergence

Learning Objectives

- Identify examples of convergence in contemporary life.

- Name the five types of convergence identified by Henry Jenkins.

- Recognize how convergence is affecting culture and society.

It’s important to keep in mind that the implementation of new technologies doesn’t mean that the old ones simply vanish into dusty museums. Today’s media consumers still watch television, listen to radio, read newspapers, and become immersed in movies. The difference is that it’s now possible to do all those things through one device—be it a personal computer or a smartphone—and through the Internet. Such actions are enabled by media convergenceThe process by which previously distinct technologies come to share tasks and resources., the process by which previously distinct technologies come to share tasks and resources. A cell phone that also takes pictures and video is an example of the convergence of digital photography, digital video, and cellular telephone technologies. An extreme, and currently nonexistent, example of technological convergence would be the so-called black box, which would combine all the functions of previously distinct technology and would be the device through which we’d receive all our news, information, entertainment, and social interaction.

Kinds of Convergence

But convergence isn’t just limited to technology. Media theorist Henry Jenkins argues that convergence isn’t an end result (as is the hypothetical black box), but instead a process that changes how media is both consumed and produced. Jenkins breaks convergence down into five categories:

- Economic convergence occurs when a company controls several products or services within the same industry. For example, in the entertainment industry a single company may have interests across many kinds of media. For example, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation is involved in book publishing (HarperCollins), newspapers (New York Post, The Wall Street Journal), sports (Colorado Rockies), broadcast television (Fox), cable television (FX, National Geographic Channel), film (20th Century Fox), Internet (MySpace), and many other media.

- Organic convergence is what happens when someone is watching a television show online while exchanging text messages with a friend and also listening to music in the background—the “natural” outcome of a diverse media world.

- Cultural convergence has several aspects. Stories flowing across several kinds of media platforms is one component—for example, novels that become television series (True Blood); radio dramas that become comic strips (The Shadow); even amusement park rides that become film franchises (Pirates of the Caribbean). The character Harry Potter exists in books, films, toys, and amusement park rides. Another aspect of cultural convergence is participatory cultureA culture in which media consumers are able to annotate, comment on, remix, and otherwise respond to culture.—that is, the way media consumers are able to annotate, comment on, remix, and otherwise influence culture in unprecedented ways. The video-sharing website YouTube is a prime example of participatory culture. YouTube gives anyone with a video camera and an Internet connection the opportunity to communicate with people around the world and create and shape cultural trends.

- Global convergence is the process of geographically distant cultures influencing one another despite the distance that physically separates them. Nigeria’s cinema industry, nicknamed Nollywood, takes its cues from India’s Bollywood, which is in turn inspired by Hollywood in the United States. Tom and Jerry cartoons are popular on Arab satellite television channels. Successful American horror movies The Ring and The Grudge are remakes of Japanese hits. The advantage of global convergence is access to a wealth of cultural influence; its downside, some critics posit, is the threat of cultural imperialismThe theory that certain cultures are attracted or pressured into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of a different culture, one that generally wields more economic power., defined by Herbert Schiller as the way developing countries are “attracted, pressured, forced, and sometimes bribed into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of the dominating centre of the system.”Livingston A. White, “Reconsidering Cultural Imperialism Theory,” TBS Journal 6 (2001), http://www.tbsjournal.com/Archives/Spring01/white.html. Cultural imperialism can be a formal policy or can happen more subtly, as with the spread of outside influence through television, movies, and other cultural projects.

- Technological convergence is the merging of technologies such as the ability to watch TV shows online on sites like Hulu or to play video games on mobile phones like the Apple iPhone. When more and more different kinds of media are transformed into digital content, as Jenkins notes, “we expand the potential relationships between them and enable them to flow across platforms.”Henry Jenkins, “Convergence? I Diverge,” Technology Review, June 2001, 93.

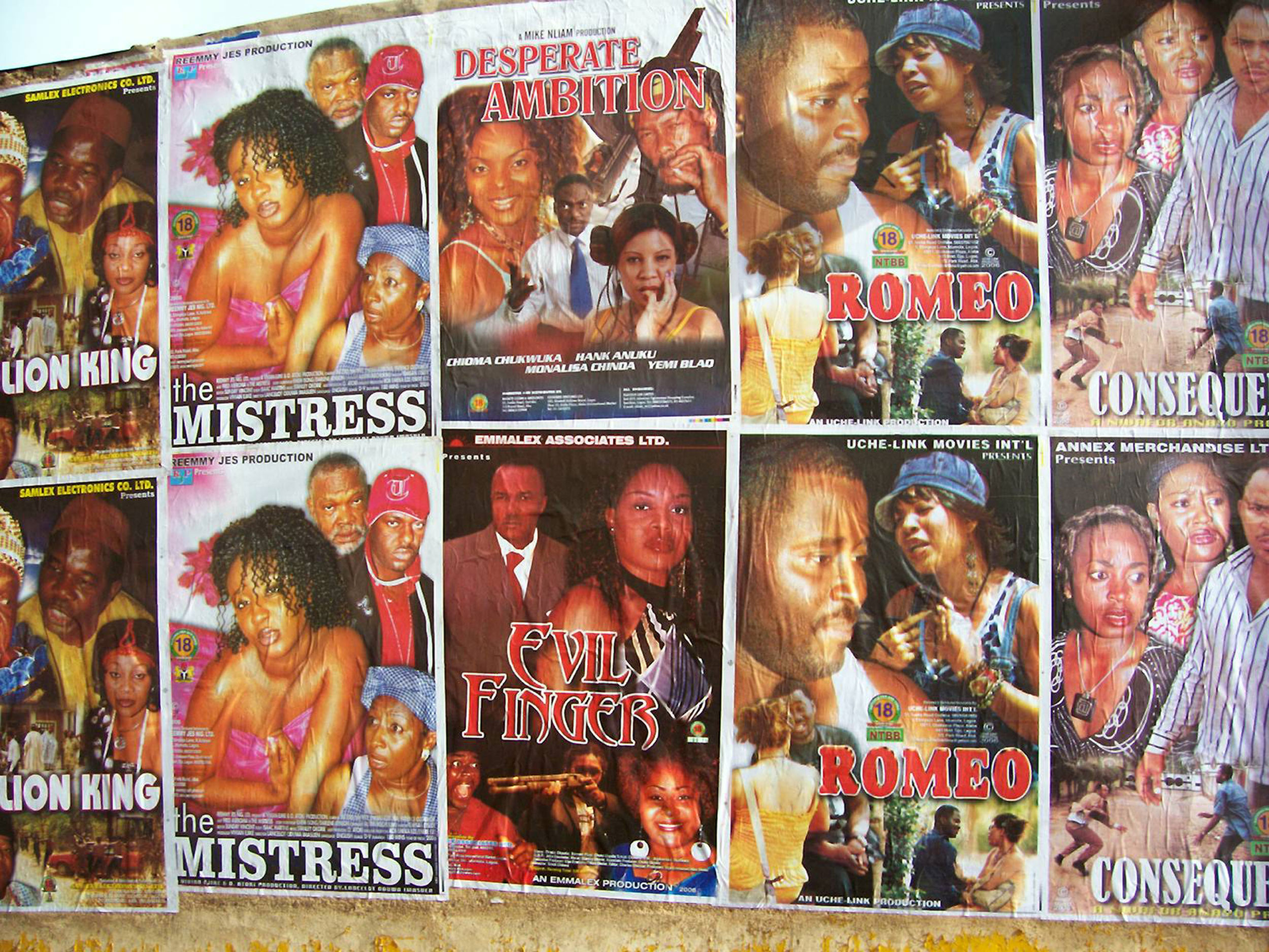

Figure 1.7

Nigeria’s Nollywood produces more films annually than any other country besides India.

Effects of Convergence

Jenkins’s concept of organic convergence is perhaps the most telling. To many people, especially those who grew up in a world dominated by so-called old media, there is nothing organic about today’s media-dominated world. As a New York Times editorial recently opined, “Few objects on the planet are farther removed from nature—less, say, like a rock or an insect—than a glass and stainless steel smartphone.”Editorial, “The Half-Life of Phones,” New York Times, June 18, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/opinion/20sun4.html1. But modern American culture is plugged in as never before, and today’s high school students have never known a world where the Internet didn’t exist. Such a cultural sea change causes a significant generation gap between those who grew up with new media and those who didn’t.

A 2010 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Americans aged 8 to 18 spend more than 7.5 hours with electronic devices each day—and, thanks to multitasking, they’re able to pack an average of 11 hours of media content into that 7.5 hours.Tamar Lewin, “If Your Kids Are Awake, They’re Probably Online,” New York Times, January 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/education/20wired.html. These statistics highlight some of the aspects of the new digital model of media consumption: participation and multitasking. Today’s teenagers aren’t passively sitting in front of screens, quietly absorbing information. Instead, they are sending text messages to friends, linking news articles on Facebook, commenting on YouTube videos, writing reviews of television episodes to post online, and generally engaging with the culture they consume. Convergence has also made multitasking much easier, as many devices allow users to surf the Internet, listen to music, watch videos, play games, and reply to e-mails on the same machine.

However, it’s still difficult to predict how media convergence and immersion are affecting culture, society, and individual brains. In his 2005 book Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that today’s television and video games are mentally stimulating, in that they pose a cognitive challenge and invite active engagement and problem solving. Poking fun at alarmists who see every new technology as making children stupider, Johnson jokingly cautions readers against the dangers of book reading: It “chronically understimulates the senses” and is “tragically isolating.” Even worse, books “follow a fixed linear path. You can’t control their narratives in any fashion—you simply sit back and have the story dictated to you…. This risks instilling a general passivity in our children, making them feel as though they’re powerless to change their circumstances. Reading is not an active, participatory process; it’s a submissive one.”Steven Johnson, Everything Bad Is Good for You (Riverhead, NY: Riverhead Books, 2005).

A 2010 book by Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains is more pessimistic. Carr worries that the vast array of interlinked information available through the Internet is eroding attention spans and making contemporary minds distracted and less capable of deep, thoughtful engagement with complex ideas and arguments. “Once I was a scuba diver in a sea of words,” Carr reflects ruefully. “Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: Norton, 2010). Carr cites neuroscience studies showing that when people try to do two things at once, they give less attention to each and perform the tasks less carefully. In other words, multitasking makes us do a greater number of things poorly. Whatever the ultimate cognitive, social, or technological results, convergence is changing the way we relate to media today.

Video Killed the Radio Star: Convergence Kills Off Obsolete Technology—or Does It?

When was the last time you used a rotary phone? How about a street-side pay phone? Or a library’s card catalog? When you need brief, factual information, when was the last time you reached for a volume of Encyclopedia Britannica? Odds are it’s been a while. All of these habits, formerly common parts of daily life, have been rendered essentially obsolete through the progression of convergence.

But convergence hasn’t erased old technologies; instead, it may have just altered the way we use them. Take cassette tapes and Polaroid film, for example. Influential musician Thurston Moore of the band Sonic Youth recently claimed that he only listens to music on cassette. Polaroid Corporation, creators of the once-popular instant-film cameras, was driven out of business by digital photography in 2008, only to be revived 2 years later—with pop star Lady Gaga as the brand’s creative director. Several Apple iPhone apps allow users to apply effects to photos to make them look more like a Polaroid photo.

Cassettes, Polaroid cameras, and other seemingly obsolete technologies have been able to thrive—albeit in niche markets—both despite and because of Internet culture. Instead of being slick and digitized, cassette tapes and Polaroid photos are physical objects that are made more accessible and more human, according to enthusiasts, because of their flaws. “I think there’s a group of people—fans and artists alike—out there to whom music is more than just a file on your computer, more than just a folder of MP3s,” says Brad Rose, founder of a Tulsa, Oklahoma-based cassette label.Marc Hogan, “This Is Not a Mixtape,” Pitchfork, February 22, 2010, http://pitchfork.com/features/articles/7764-this-is-not-a-mixtape/2/. The distinctive Polaroid look—caused by uneven color saturation, underdevelopment or overdevelopment, or just daily atmospheric effects on the developing photograph—is emphatically analog. In an age of high resolution, portable printers, and camera phones, the Polaroid’s appeal to some has something to do with ideas of nostalgia and authenticity. Convergence has transformed who uses these media and for what purposes, but it hasn’t eliminated these media.

Key Takeaways

- Twenty-first century media culture is increasingly marked by convergence, or the coming together of previously distinct technologies, as in a cell phone that also allows users to take video and check e-mail.

- Media theorist Henry Jenkins identifies the five kinds of convergence as the following:

- Economic convergence is when a single company has interests across many kinds of media.

- Organic convergence is multimedia multitasking, or the natural outcome of a diverse media world.

- Cultural convergence is when stories flow across several kinds of media platforms and when readers or viewers can comment on, alter, or otherwise talk back to culture.

- Global convergence is when geographically distant cultures are able to influence one another.

- Technological convergence is when different kinds of technology merge. The most extreme example of technological convergence would be one machine that controlled every media function.

- The jury is still out on how these different types of convergence will affect people on an individual and societal level. Some theorists believe that convergence and new-media technologies make people smarter by requiring them to make decisions and interact with the media they’re consuming; others fear the digital age is giving us access to more information but leaving us shallower.

Exercises

Review the viewpoints of Henry Jenkins, Steven Johnson, and Nicholas Carr. Then, answer the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Define convergence as it relates to mass media and provide some examples of convergence you’ve observed in your life.

- Describe the five types of convergence identified by Henry Jenkins and provide an example of each type that you’ve noted in your own experience.

- How do Steven Johnson and Nicholas Carr think convergence is affecting culture and society? Whose argument do you find more compelling and why?

1.4 The Role of Social Values in Communication

Learning Objectives

- Identify two limitations on free speech that are based on social values.

- Identify examples of propaganda in mass media.

- Explain the role of the gatekeeper in mass media.

In a 1995 Wired magazine article, “The Age of Paine,” Jon Katz suggested that the Revolutionary War patriot Thomas Paine should be considered “the moral father of the Internet.” The Internet, Katz wrote, “offers what Paine and his revolutionary colleagues hoped for—a vast, diverse, passionate, global means of transmitting ideas and opening minds.” In fact, according to Katz, the emerging Internet era is closer in spirit to the 18th-century media world than to the 20th-century’s “old media” (radio, television, print). “The ferociously spirited press of the late 1700s…was dominated by individuals expressing their opinions. The idea that ordinary citizens with no special resources, expertise, or political power—like Paine himself—could sound off, reach wide audiences, even spark revolutions, was brand-new to the world.”Ibid. Katz’s impassioned defense of Paine’s plucky independence speaks to the way social values and communication technologies are affecting our adoption of media technologies today. Keeping Katz’s words in mind, we can ask ourselves additional questions about the role of social values in communication. How do they shape our ideas of mass communication? How, in turn, does mass communication change our understanding of what our society values?

Figure 1.8

Thomas Paine is regarded by some as the “moral father of the Internet” because his independent spirit is reflected in the democratization of mass communication via the Internet.

Free Speech and Its Limitations

The value of free speech is central to American mass communication and has been since the nation’s revolutionary founding. The U.S. Constitution’s very first amendment guarantees the freedom of the press. Because of the First Amendment and subsequent statutes, the United States has some of the broadest protections on speech of any industrialized nation. However, there are limits to what kinds of speech are legally protected—limits that have changed over time, reflecting shifts in U.S. social values.

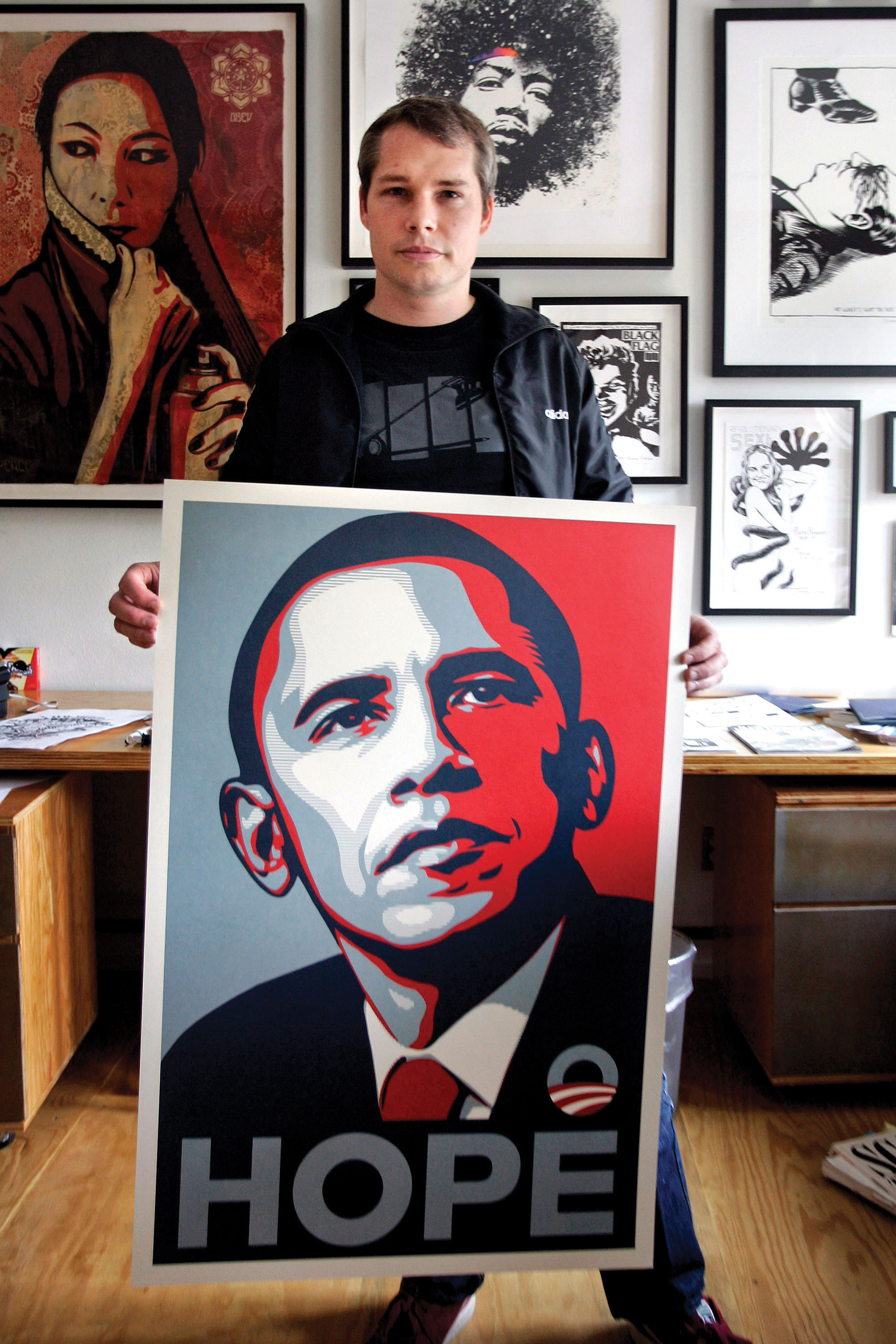

Figure 1.9

Artist Shepard Fairey, creator of the iconic Obama HOPE image, was sued by the Associated Press for copyright infringement; Fairey argued that his work was protected by the fair use exception.

Source: Used with permission from Getty Images.

Definitions of obscenityIndecency that goes against public morals and exerts a corrupting influence. Obscenity is not protected by the First Amendment., which is not protected by the First Amendment, have altered with the nation’s changing social attitudes. James Joyce’s Ulysses, ranked by the Modern Library as the best English-language novel of the 20th century, was illegal to publish in the United States between 1922 and 1934 because the U.S. Customs Court declared the book obscene because of its sexual content. The 1954 Supreme Court case Roth v. the United States defined obscenity more narrowly, allowing for differences depending on community standards. The sexual revolution and social changes of the 1960s made it even more difficult to pin down just what was meant by community standards—a question that is still under debate to this day. The mainstreaming of sexually explicit content like Playboy magazine, which is available in nearly every U.S. airport, is another indication that obscenity is still open to interpretation.

Regulations related to obscene content are not the only restrictions on First Amendment rights; copyright lawLaw that regulates the exclusive rights given to the creator of a work. also puts limits on free speech. Intellectual property law was originally intended to protect just that—the proprietary rights, both economic and intellectual, of the originator of a creative work. Works under copyright can’t be reproduced without the authorization of the creator, nor can anyone else use them to make a profit. Inventions, novels, musical tunes, and even phrases are all covered by copyright law. The first copyright statute in the United States set 14 years as the maximum term for copyright protection. This number has risen exponentially in the 20th century; some works are now copyright-protected for up to 120 years. In recent years, an Internet culture that enables file sharing, musical mash-ups, and YouTube video parodies has raised questions about the fair use exception to copyright law. The exact line between what types of expressions are protected or prohibited by law are still being set by courts, and as the changing values of the U.S. public evolve, copyright law—like obscenity law—will continue to change as well.

Propaganda and Other Ulterior Motives

Sometimes social values enter mass media messages in a more overt way. Producers of media content may have vested interests in particular social goals, which, in turn, may cause them to promote or refute particular viewpoints. In its most heavy-handed form, this type of media influence can become propagandaCommunication that intentionally attempts to persuade its audience for ideological, political, or commercial purposes., communication that intentionally attempts to persuade its audience for ideological, political, or commercial purposes. Propaganda often (but not always) distorts the truth, selectively presents facts, or uses emotional appeals. During wartime, propaganda often includes caricatures of the enemy. Even in peacetime, however, propaganda is frequent. Political campaign commercials in which one candidate openly criticizes the other are common around election time, and some negative ads deliberately twist the truth or present outright falsehoods to attack an opposing candidate.

Other types of influence are less blatant or sinister. Advertisers want viewers to buy their products; some news sources, such as Fox News or The Huffington Post, have an explicit political slant. Still, people who want to exert media influence often use the tricks and techniques of propaganda. During World War I, the U.S. government created the Creel Commission as a sort of public relations firm for the United States’ entry into the war. The Creel Commission used radio, movies, posters, and in-person speakers to present a positive slant on the U.S. war effort and to demonize the opposing Germans. Chairman George Creel acknowledged the commission’s attempt to influence the public but shied away from calling their work propaganda:

In no degree was the Committee an agency of censorship, a machinery of concealment or repression…. In all things, from first to last, without halt or change, it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventures in advertising…. We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts.George Creel, How We Advertised America (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920).

Of course, the line between the selective (but “straightforward”) presentation of the truth and the manipulation of propaganda is not an obvious or distinct one. (Another of the Creel Commission’s members was later deemed the father of public relations and authored a book titled Propaganda.) In general, however, public relations is open about presenting one side of the truth, while propaganda seeks to invent a new truth.

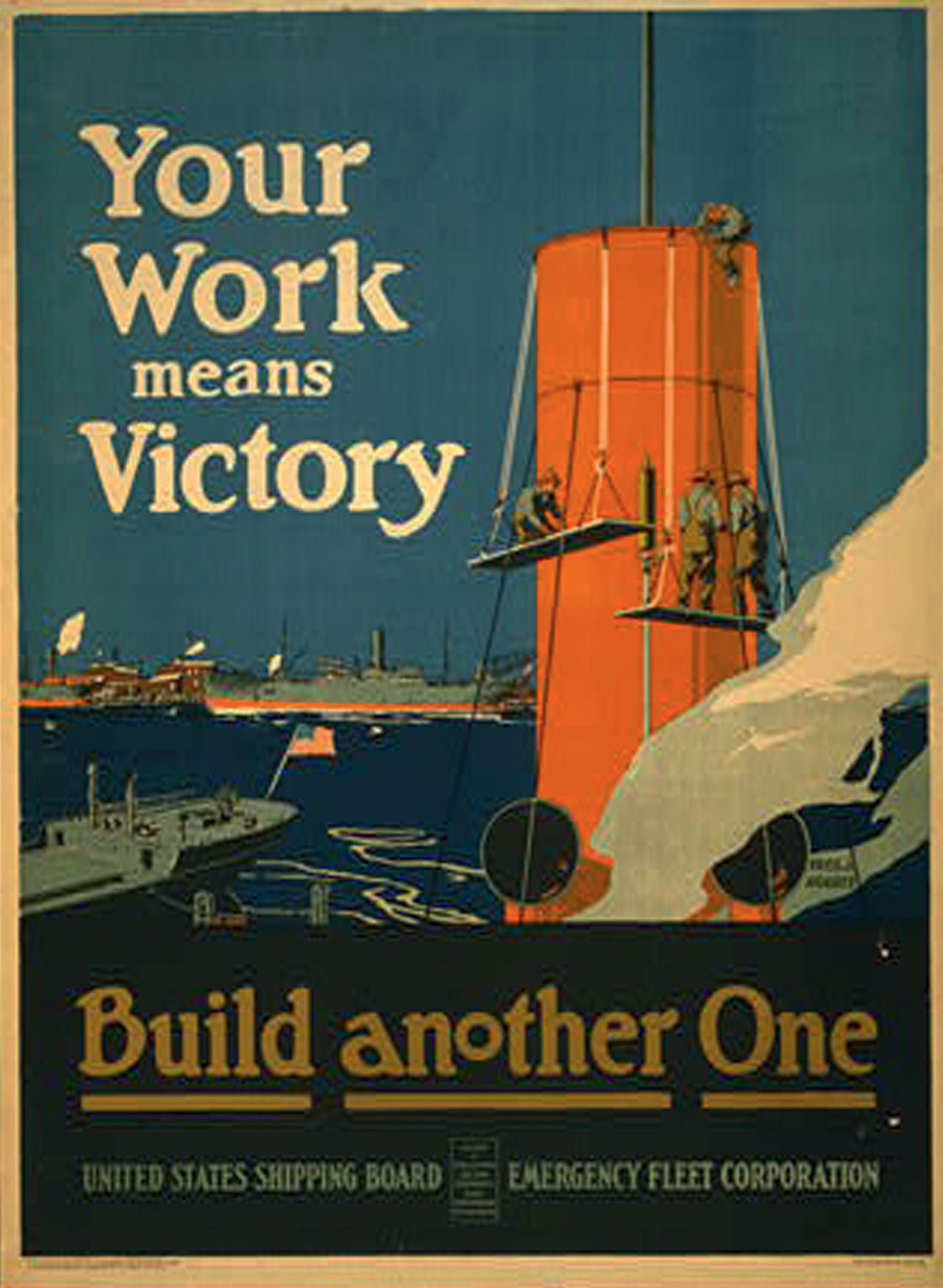

Figure 1.10

World War I propaganda posters were sometimes styled to resemble movie posters in an attempt to glamorize the war effort.

Gatekeepers

In 1960, journalist A. J. Liebling wryly observed that “freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Liebling was referring to the role of gatekeepers in the media industry, another way in which social values influence mass communication. GatekeepersThe people who help determine which stories make it to the public, including reporters who decide what sources to use and editors who pick which topics are reported on and which stories make it to the front page. are the people who help determine which stories make it to the public, including reporters who decide what sources to use and editors who decide what gets reported on and which stories make it to the front page. Media gatekeepers are part of society and thus are saddled with their own cultural biases, whether consciously or unconsciously. In deciding what counts as newsworthy, entertaining, or relevant, gatekeepers pass on their own values to the wider public. In contrast, stories deemed unimportant or uninteresting to consumers can linger forgotten in the back pages of the newspaper—or never get covered at all.

In one striking example of the power of gatekeeping, journalist Allan Thompson lays blame on the news media for its sluggishness in covering the Rwandan genocide in 1994. According to Thompson, there weren’t many outside reporters in Rwanda at the height of the genocide, so the world wasn’t forced to confront the atrocities happening there. Instead, the nightly news in the United States was preoccupied by the O. J. Simpson trial, Tonya Harding’s attack on a fellow figure skater, and the less bloody conflict in Bosnia (where more reporters were stationed). Thompson went on to argue that the lack of international media attention allowed politicians to remain complacent.Allan Thompson, “The Media and the Rwanda Genocide” (lecture, Crisis States Research Centre and POLIS at the London School of Economics, January 17, 2007), http://www2.lse.ac.uk/publicEvents/pdf/20070117_PolisRwanda.pdf. With little media coverage, there was little outrage about the Rwandan atrocities, which contributed to a lack of political will to invest time and troops in a faraway conflict. Richard Dowden, Africa editor for the British newspaper The Independent during the Rwandan genocide, bluntly explained the news media’s larger reluctance to focus on African issues: “Africa was simply not important. It didn’t sell newspapers. Newspapers have to make profits. So it wasn’t important.”Ibid. Bias on the individual and institutional level downplayed the genocide at a time of great crisis and potentially contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Gatekeepers had an especially strong influence in old media, in which space and time were limited. A news broadcast could only last for its allotted half hour, while a newspaper had a set number of pages to print. The Internet, in contrast, theoretically has room for infinite news reports. The interactive nature of the medium also minimizes the gatekeeper function of the media by allowing media consumers to have a voice as well. News aggregators like Digg allow readers to decide what makes it on to the front page. That’s not to say that the wisdom of the crowd is always wise—recent top stories on Digg have featured headlines like “Top 5 Hot Girls Playing Video Games” and “The girl who must eat every 15 minutes to stay alive.” Media expert Mark Glaser noted that the digital age hasn’t eliminated gatekeepers; it’s just shifted who they are: “the editors who pick featured artists and apps at the Apple iTunes store, who choose videos to spotlight on YouTube, and who highlight Suggested Users on Twitter,” among others.Mark Glaser, “New Gatekeepers Twitter, Apple, YouTube Need Transparency in Editorial Picks,” PBS Mediashift, March 26, 2009, http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2009/03/new-gatekeepers-twitter-apple-youtube-need-transparency-in-editorial-picks085.html. And unlike traditional media, these new gatekeepers rarely have public bylines, making it difficult to figure out who makes such decisions and on what basis they are made.

Observing how distinct cultures and subcultures present the same story can be indicative of those cultures’ various social values. Another way to look critically at today’s media messages is to examine how the media has functioned in the world and in the United States during different cultural periods.

Key Takeaways

- American culture puts a high value on free speech; however, other societal values sometimes take precedence. Shifting ideas about what constitutes obscenity, a kind of speech that is not legally protected by the First Amendment, is a good example of how cultural values impact mass communication—and of how those values change over time. Copyright law, another restriction put on free speech, has had a similar evolution over the nation’s history.

- Propaganda is a type of communication that attempts to persuade the audience for ideological, political, or social purposes. Some propaganda is obvious, explicit, and manipulative; however, public relations professionals borrow many techniques from propaganda and they try to influence their audience.

- Gatekeepers influence culture by deciding which stories are considered newsworthy. Gatekeepers can promote social values either consciously or subconsciously. The digital age has lessened the power of gatekeepers somewhat, as the Internet allows for nearly unlimited space to cover any number of events and stories; furthermore, a new gatekeeper class has emerged on the Internet as well.

Exercises

Please answer the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Find an advertisement—either in print, broadcast, or online—that you have recently found to be memorable. Now find a nonadvertisement media message. Compare the ways that the ad and the nonad express social values. Are the social values the same for each of them? Is the influence overt or covert? Why did the message’s creators choose to present their message in this way? Can this be considered propaganda?

- Go to a popular website that uses user-uploaded content (YouTube, Flickr, Twitter, Metafilter, etc.). Look at the content on the site’s home page. Can you tell how this particular content was selected to be featured? Does the website list a policy for featured content? What factors do you think go into the selection process?

- Think of two recent examples where free speech was limited because of social values. Who were the gatekeepers in these situations? What effect did these limitations have on media coverage?

1.5 Cultural Periods

Learning Objectives

- Identify recent cultural periods.

- Identify the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the modern era.

- Explain the ways that the postmodern era differs from the modern era.

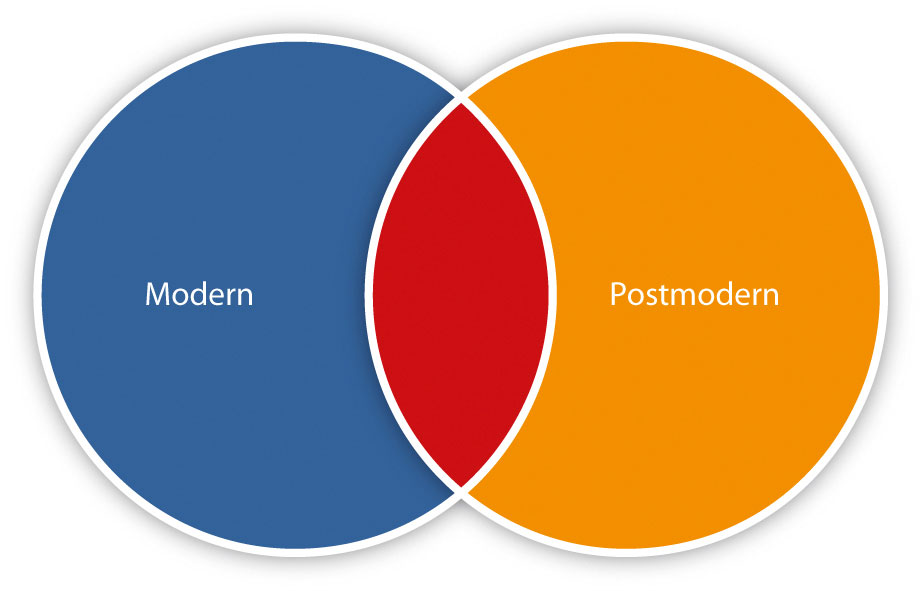

Table 1.1 Cultural Periods

|

Modern Era |

Early Modern Period (late 1400s–1700s) |

Began with Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the movable type printing press; characterized by improved transportation, educational reform, and scientific inquiry. |

|

Late Modern Period (1700s–1900s) |

Sparked by the Industrial Revolution; characterized by technical innovations, increasingly secular politics, and urbanization. |

|

|

Postmodern Age (1950s–present) |

Marked by skepticism, self-consciousness, celebration of differences, and the digitalization of culture. |

After exploring the ways technology, culture, and mass media have affected one another over the years, it may also be helpful to look at recent cultural eras more broadly. A cultural periodA time marked by a particular way of understanding the world through culture and technology. is a time marked by a particular way of understanding the world through culture and technology. Changes in cultural periods are marked by fundamental switches in the way people perceive and understand the world. In the Middle Ages, truth was dictated by authorities like the king and the church. During the Renaissance, people turned to the scientific method as a way to reach truth through reason. And, in 2008, Wired magazine’s editor in chief proclaimed that Google was about to render the scientific method obsolete.Chris Anderson, “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete,” Wired, June 23, 2008, http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/magazine/16-07/pb_theory. In each of these cases, it wasn’t that the nature of truth changed, but the way humans attempted to make sense of a world that was radically changing. For the purpose of studying culture and mass media, the post-Gutenberg modern and postmodern ages are the most relevant ones to explore.

The Modern Age

The Modern AgeThe postmedieval era; a wide span of time marked in part by technological innovations, urbanization, scientific discoveries, and globalization., or modernity, is the postmedieval era, a wide span of time marked in part by technological innovations, urbanization, scientific discoveries, and globalization. The Modern Age is generally split into two parts: the early and the late modern periods.

The early modern period began with Gutenberg’s invention of the movable type printing press in the late 15th century and ended in the late 18th century. Thanks to Gutenberg’s press, the European population of the early modern period saw rising literacy rates, which led to educational reform. As noted in preceding sections, Gutenberg’s machine also greatly enabled the spread of knowledge and, in turn, spurred the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. During the early modern period, transportation improved, politics became more secularized, capitalism spread, nation-states grew more powerful, and information became more widely accessible. Enlightenment ideals of reason, rationalism, and faith in scientific inquiry slowly began to replace the previously dominant authorities of king and church.

Huge political, social, and economic changes marked the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the late modern period. The Industrial Revolution, which began in England around 1750, combined with the American Revolution in 1776 and the French Revolution in 1789, marked the beginning of massive changes in the world.

The French and American revolutions were inspired by a rejection of monarchy in favor of national sovereignty and representative democracy. Both revolutions also heralded the rise of secular society as opposed to church-based authority systems. Democracy was well suited to the so-called Age of Reason, with its ideals of individual rights and progress.

Though less political, the Industrial Revolution had equally far-reaching consequences. It did not merely change the way goods were produced—it also fundamentally changed the economic, social, and cultural framework of its time. The Industrial Revolution doesn’t have clear start or end dates. However, during the 19th century, several crucial inventions—the internal combustion engine, steam-powered ships, and railways, among others—led to innovations in various industries. Steam power and machine tools increased production dramatically. But some of the biggest changes coming out of the Industrial Revolution were social in character. An economy based on manufacturing instead of agriculture meant that more people moved to cities, where techniques of mass production led people to value efficiency both in and out of the factory. Newly urbanized factory laborers could no longer produce their own food, clothing, or supplies, and instead turned to consumer goods. Increased production led to increases in wealth, though income inequalities between classes also started to grow.

These overwhelming changes affected (and were affected by) the media. As noted in preceding sections, the fusing of steam power and the printing press enabled the explosive expansion of books and newspapers. Literacy rates rose, as did support for public participation in politics. More and more people lived in the city, had an education, got their news from the newspaper, spent their wages on consumer goods, and identified as citizens of an industrialized nation. Urbanization, mass literacy, and new forms of mass media contributed to a sense of mass culture that united people across regional, social, and cultural boundaries.

Modernity and the Modern Age, it should be noted, are distinct from (but related to) the cultural movement of modernism. The Modern Era lasted from the end of the Middle Ages to the middle of the 20th century; modernismAn artistic movement of late 19th and early 20th centuries that arose from the widespread changes that swept the world during that period and that is characterized by people questioning the limitations of traditional forms of art and culture., however, refers to the artistic movement of late 19th and early 20th centuries that arose from the widespread changes that swept the world during that period. Most notably, modernism questioned the limitations of traditional forms of art and culture. Modernist art was in part a reaction against the Enlightenment’s certainty of progress and rationality. It celebrated subjectivity through abstraction, experimentalism, surrealism, and sometimes pessimism or even nihilism. Prominent examples of modernist works include James Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness novels, cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso, atonal compositions by Claude Debussy, and absurdist plays by Luigi Pirandello.

The Postmodern Age

Modernism can also be seen as a transitional phase between the modern and postmodern eras. While the exact definition and dates of the Postmodern AgeA cultural period that began during the second half of the 20th century and that was marked by skepticism, self-consciousness, celebration of difference, and the reappraisal of modern conventions. are still being debated by cultural theorists and philosophers, the general consensus is that the Postmodern Age began during the second half of the 20th century and was marked by skepticism, self-consciousness, celebration of difference, and the reappraisal of modern conventions. The Modern Age took for granted scientific rationalism, the autonomous self, and the inevitability of progress; the Postmodern Age questioned or dismissed many of these assumptions. If the Modern Age valued order, reason, stability, and absolute truth, the Postmodern Age reveled in contingency, fragmentation, and instability. The effect of technology on culture, the rise of the Internet, and the Cold War are all aspects that led to the Postmodern Age.

The belief in objective truth that characterized the Modern Age is one of the major assumptions overturned in the Postmodern Age. Postmodernists instead took their cues from Erwin Schrödinger, the quantum physicist who famously devised a thought experiment in which a cat is placed inside a sealed box with a small amount of radiation that may or may not kill it. While the box remains sealed, Schrödinger proclaimed, the cat exists simultaneously in both states, dead and alive. Both potential states are equally true. Although the thought experiment was devised to explore issues in quantum physics, it appealed to postmodernists in its assertion of radical uncertainty. Rather than there being an absolute objective truth accessible by rational experimentation, the status of reality was contingent and depended on the observer.

This value of the relative over the absolute found its literary equivalent in the movement of deconstruction. While Victorian novelists took pains to make their books seem more realistic, postmodern narratives distrusted professions of reality and constantly reminded readers of the artificial nature of the story they were reading. The emphasis was not on the all-knowing author, but instead on the reader. For the postmodernists, meaning was not injected into a work by its creator, but depended on the reader’s subjective experience of the work. The poetry of Sylvia Plath and Allen Ginsberg exemplify this, as much of their work is emotionally charged and designed to create a dialogue with the reader, oftentimes forcing the reader to confront controversial issues such as mental illness or homosexuality.

Another way the Postmodern Age differed from the Modern Age was in the rejection of what philosopher Jean-François Lyotard deemed “grand narrativesLarge-scale theories that attempt to explain the totality of human experience..” The Modern Age was marked by different large-scale theories that attempted to explain the totality of human experience, such as capitalism, Marxism, rationalism, Freudianism, Darwinism, fascism, and so on. However, increasing globalization and the rise of subcultures called into question the sorts of theories that claimed to explain everything at once. Totalitarian regimes during the 20th century, such as Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich and the USSR under Joseph Stalin, led to a mistrust of power and the systems held up by power. The Postmodern Age, Lyotard theorized, was one of micronarratives instead of grand narratives—that is, a multiplicity of small, localized understandings of the world, none of which can claim an ultimate or absolute truth. An older man in Kenya, for example, does not view the world in the same way as a young woman from New York. Even people from the same cultural backgrounds have different views of the world—when you were a teenager, did your parents understand your way of thinking? The diversity of human experience is a marked feature of the postmodern world. As Lyotard noted, “Eclecticism is the degree zero of contemporary general culture; one listens to reggae, watches a Western, eats McDonald’s food for lunch and local cuisine for dinner, wears Paris perfume in Tokyo and retro clothes in Hong Kong; knowledge is a matter for TV games.”Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

Postmodernists also mistrusted the idea of originality and freely borrowed across cultures and genres. William S. Burroughs gleefully proclaimed a sort of call to arms for his generation of writers in 1985: “Out of the closets and into the museums, libraries, architectural monuments, concert halls, bookstores, recording studios and film studios of the world. Everything belongs to the inspired and dedicated thief.”William S. Burroughs, “Les Velours,” The Adding Machine, (New York: Arcade Publishing, 1993), 19–21. The feminist artist Barbara Kruger, for example, creates works of art from old advertisements, and writers, such as Kathy Acker, reconstructed existing texts to form new stories. The rejection of traditional forms of art and expression embody the Postmodern Age.

From the early Modern Age through the Postmodern Age, people have experienced the world in vastly different ways. Not only has technology rapidly become more complex, but culture itself has changed with the times. When reading further, it’s important to remember that forms of media and culture are hallmarks of different eras, and the different ways in which media are presented often tell us a lot about the culture and times.

Key Takeaways

- A cultural period is a time marked by a particular way of understanding the world through culture and technology. Changes in cultural periods are marked by fundamental changes in the way we perceive and understand the world. The Modern Age began after the Middle Ages and lasted through the early decades of the 20th century, when the Postmodern Age began.