This is “Writing about Readers: Applying Reader-Response Theory”, chapter 6 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 6 Writing about Readers: Applying Reader-Response Theory

Learning Objectives

- Understand the theory of reader response, which focuses on the reader’s reading experience.

- Apply the reader-response methodology to works of literature.

- Engage in the writing process of a peer writer, including peer review.

- Review and evaluate a variety of reader-response papers by peer writers.

- Draft and revise a reader-response paper on a literary work.

6.1 Literary Snapshot: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Lewis Carroll, as we found out in previous chapters, is most famous for two books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1872). These books follow the adventures of the 7–year-old, Alice, who tumbles down a rabbit hole (Wonderland) and enters a magic mirror (Looking-Glass), entering a nonsensical world of the imagination. If you have not already read these classic books—or wish to reread them—you can access them at the following links:

http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html

Alice finds herself challenged to make sense of a seemingly absurd world inhabited by odd creatures. Throughout her adventures, Alice attempts to apply logic to her experiences; in other words, Alice tries to interpret and find meaning in Wonderland and Looking-Glass Land.

Alice acts like a literary critic. In previous chapters, you became like Alice—that is, you learned about a literary theory and applied that theory as you analyzed a work of literature. This chapter asks you to reimagine your role as a literary critic: you will be asked to analyze not only the text but also the role of the reader in constructing meaning. In a sense, you will be asked to be a lot like Alice, trying to figure out your reading experience as you immerse yourself in a literary creation.

Our scene comes from chapter 10, “The Lobster-Quadrille” in Wonderland:

“Stand up and repeat “‘’Tis the voice of the sluggard,’” said the Gryphon.

“How the creatures order one about, and make one repeat lessons!” thought Alice; “I might as well be at school at once.” However, she got up, and began to repeat it, but her head was so full of the Lobster Quadrille, that she hardly knew what she was saying, and the words came very queer indeed:—

“’Tis the voice of the Lobster; I heard him declare,

‘You have baked me too brown, I must sugar my hair.’

As a duck with its eyelids, so he with his nose

Trims his belt and his buttons, and turns out his toes.

When the sands are all dry, he is gay as a lark,

And will talk in contemptuous tones of the Shark:

But, when the tide rises and sharks are around,

His voice has a timid and tremulous sound.”

“That’s different from what I used to say when I was a child,” said the Gryphon.

“Well, I never heard it before,” said the Mock Turtle; “but it sounds uncommon nonsense.”

Alice said nothing; she had sat down with her face in her hands, wondering if anything would ever happen in a natural way again.

“I should like to have it explained,” said the Mock Turtle.

“She can’t explain it,” said the Gryphon hastily. “Go on with the next verse.”

“But about his toes?” the Mock Turtle persisted. “How could he turn them out with his nose, you know?”

“It’s the first position in dancing.” Alice said; but was dreadfully puzzled by the whole thing, and longed to change the subject.

“Go on with the next verse,” the Gryphon repeated impatiently: “it begins ‘I passed by his garden.’”

Alice did not dare to disobey, though she felt sure it would all come wrong, and she went on in a trembling voice:—

“I passed by his garden, and marked, with one eye,

How the Owl and the Panther were sharing a pie:

The Panther took pie-crust, and gravy, and meat,

While the Owl had the dish as its share of the treat.

When the pie was all finished, the Owl, as a boon,

Was kindly permitted to pocket the spoon:

While the Panther received knife and fork with a growl,

And concluded the banquet—”

“What is the use of repeating all that stuff,” the Mock Turtle interrupted, “if you don’t explain it as you go on? It’s by far the most confusing thing I ever heard!”

“Yes, I think you’d better leave off,” said the Gryphon: and Alice was only too glad to do so.Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. With Forty-Two Illustrations by John Tenniel (New York: D. Appleton, 1927; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1998), chap. 10, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html.

Alice finds herself reciting a poem about a Lobster and then continuing with a poem about an Owl and a Panther. Not only is Alice creating—that is, she makes up these poems—but she also requires the reader to finish the second poem:

While the Panther received knife and fork with a growl,

And concluded the banquet—

By eating the Owl!

“By eating the Owl!” The poem nudges the reader to complete the line by filling in the final ending to the poem: we know that the Panther will eat the Owl. Of course, a reader might complete the poem by writing, “by throwing in the towel,” or “by picking up a trowel,” “by running down the hall,” or even “with an even greater howl.” In any case, you, as the reader, have activated the text.

You have engaged in the theory of reader response.

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

Reader-response theory suggests that the role of the reader is essential to the meaning of a literary text, for only in the reading experience does the literary work come alive. Frankenstein (1818) doesn’t exist, so to speak, until the reader reads Frankenstein and reanimates it to life, becoming a cocreator of the text.Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein (1831; University of Virginia Electronic Text Center, 1994), http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/SheFran.html.

Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar.”

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion every where.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

Class Process

- Read Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar.”Wallace Stevens, “Anecdote of a Jar,” University of Pennsylvania, http://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88/stevens-ancedote.html.

- Write down your reading experience: What went on in your mind while you were reading the poem? Did you like the poem? Dislike it? Were you confused by the poem?

- Jot down what you think the poem is about—the theme of the poem.

- Break into groups of three or four. Compare your experiences with each other. Then compare your interpretations.

- List the student-group interpretations on the blackboard, whiteboard, or other high- or low-tech medium into two categories: Experiences While Reading and Interpretation of the Poem.

- Discuss the differences between the reading experience and the ways the students interpreted the poem.

6.2 Reader-Response Theory: An Overview

Let’s begin with the famous opening from Jane Austen’s Emma (1816):“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.”Jane Austen, Emma (New York: Penguin Classics, 2011).

Oh, that Emma Woodhouse. “Handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition,” certainly, but also vain, proud, and a mischievous-matchmaker in those things related to love. Not much of a character to base a novel on, the reader might muse. Austen was nervous about her creation of Emma, for as she wrote in a letter: “I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.” Yet Austen does exactly this: in Emma, she creates a character that taxes the reader’s patience, one the author recognizes that readers may not like.

Austen’s comments on Emma point to the fact that readers identify with characters in a novel. And we can extrapolate further: readers like or dislike what they read; readers are moved to joy, anger, sadness, and so on by a literary work; and readers read literature from a personal level. For an author, this “reader response” is of utmost importance, as Austen most certainly realizes. If readers do not like Emma, do not empathize with her on some emotional level, then they will dislike the novel.

Class Process

- List the literary works that you were told were great or important but that you actually disliked. Your instructor should also share his or her dislikes. This should lead to a lively discussion.

You will see that “likes” and “dislikes” are important markers in reader-response theory. Here’s an example: in Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen (1984), the author, Fay Weldon, writes to her niece Alice, trying to convince her of the importance of Austen. “You tell me in passing,” writes Weldon, “that you are doing a college course in English Literature, and are obliged to read Jane Austen; that you find her boring, petty and irrelevant and, that as the world is in crisis, and the future catastrophic, you cannot imagine what purpose there can be in your reading her.”Fay Weldon, Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2011), 11. Weldon responds, “Emma opens with a paragraph which sends shivers of pleasure down my spine: it glitters with sheer competence: with the animation of the writer who has discovered power: who is at ease in the pathways of the City of Invention. Here is Emma, exciting envy in the heart of the reader and also, one suspects, the writer—and now, she declares, Emma will be undone; and I, the writer, and you, the reader, will share in this experience.”Fay Weldon, Letters to Alice on First Reading Jane Austen (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2011), 96. Weldon, of course, is responding to Austen on a very personal level—on the gut level we should say—which can make one have “shivers of pleasure” or “exciting envy” or “share in this [reading] experience.” What Weldon does to Austen and Emma is perform a reader-response interpretation.

Reader-response literary criticism recognizes the simple fact that readers respond to literature on an emotional level and that such responses are important to the understanding of the work. Long ago, even Aristotle recognized how important an audience’s reaction is to tragedy, for a key to tragedy is catharsisAn emotional release. The Greek philosopher Aristotle argued that plays, or literature, should provide this experience for their audience., the purging of the audience’s emotions. If you recall from Chapter 1 "Introduction: What Is Literary Theory and Why Should I Care?", the concept of the affective fallacy was central to the New Critical methodology—a reader was never to confuse the interpretation of the literary work with the “feeling” she or he had while reading. These New Critics warned the reader that affective responses lead only to subjectivity; thus New Critics suggested that the reader pay close attention to the intricacies of the text under observation for meaning, for the text as a well-wrought urn contains meaning.

Reader-response critics, on the other hand, embrace the affective fallacy (what reader-response critic Stanley Fish has called the “affective fallacy fallacyTerm coined by Stanley Fish to express reader-response critics’ rejection of the New Critics’ affective fallacy. Reader-response critics believe that we should not repress our personal responses to literature but rather explore them in our writing.”), for they believe that a reader’s affective response is importance to criticism.Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). Instead of focusing on literature as a well-wrought urn, reader-response critics focus on the reader, who “completes” or “activates” the text as he or she reads. In a sense, the reader becomes the most important element in the reading process, supplanting even the author.

When you think about it, reader-response criticism makes perfect sense. How many times have you become so immersed in a work that you are oblivious to the world around you? If you like fantasy literature, you might still recall the first time you read the Harry Potter series—you were transported out of your Muggle world into the magical Hogwarts, where Harry and his friends battle the dark forces of the one we should not name. How many of you stood in line to get your copy of the latest Harry Potter novel at midnight? Or camped out at the theater to be one of the first to see the final installment of The Deathly Hallows? There may even be a few of you who are not Potter fans, but be warned—don’t share those thoughts too readily! A case point: one of the editors of this textbook, John Pennington, found this out quite clearly. He teaches a general-education course called Science Fiction and Fantasy, which attracts die-hard fans of these popular forms of fiction. When the first volume of the Harry Potter series came out, he was approached by a student, who told him that this was the best fantasy literature since J. R. R. Tolkien, maybe even better. Quite a claim, and one that came from a very intelligent student who clearly was excited about Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone! However, Pennington found that he did not enjoy the novel as much as his student had. So he read the next volume, and the next, and…you get the picture. To put it bluntly, he wasn’t that impressed with the Harry Potter series. He eventually published an article in The Lion and the Unicorn, a critical journal that focuses on children’s literature. In that article, he critiques the Harry Potter series as ineffective—shall we say, “failed”—fantasy literature.John Pennington, “From Elfland to Hogwarts, or the Aesthetic Trouble with Harry Potter,” The Lion and the Unicorn 26, no. 1 (2002): 78–97, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lion_and_the_unicorn/toc/uni26.1.html.

Over the years, he has received emails from students who are doing research papers on Harry Potter. To demonstrate that literature is often read with passion, read the following e-mail to John Pennington, which he received from a student who was doing such a research paper:

Hello, Professor Pennington. My name is Emily. I'm a senior English major at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, TX.

For my honors thesis, I have been doing research on fantasy literature (I’m making a comparison of magical and fantastic creatures in American and British literature) and in my search, I stumbled across your piece “From Elfland to Hogwarts, or the Aesthetic Trouble with Harry Potter.” I won’t lie to you, I am an avid Harry Potter fan. I am the president of the St. Mary’s Harry Potter club, called Dumbledore’s Army.

Mary’s Harry Potter club, called Dumbledore’s Army. I was just wondering if your feelings about certain aspects of the Harry Potter series have changed now that all the books have been released? I definitely agreed with some of your opinions and arguments (even as a little girl reading the books I made the connection between Tolkien/Rowling and Lewis/Rowling), but there are also instances in which I feel you were being too harsh. For instance, you said that while Voldemort was clearly the representation of the archetype for evil, there was none for good. I disagree. I don't believe that the figure for good needs to be a person or being at all. Instead, in the case of the Harry Potter, the symbol of the good archetype is love. Although, arguably, good and love could be seen as synonyms in some cases (through the right analytic lens), I think that love’s manifestations in the Harry Potter series are what truly combats Voldemort (rather than Harry’s attempts at battle—another aspect I, and indeed Harry, agree with you on: all he had was luck) and therefore become the figure of good.

I did find your piece helpful for my research and I do plan to read more of your published works in the future.

One other question: Do you often get e-mails from people who are disgruntled by your criticism of the Potter series? I would imagine the answer is yes.

Thank you for your time.

—Emily Bryant-Mundschau

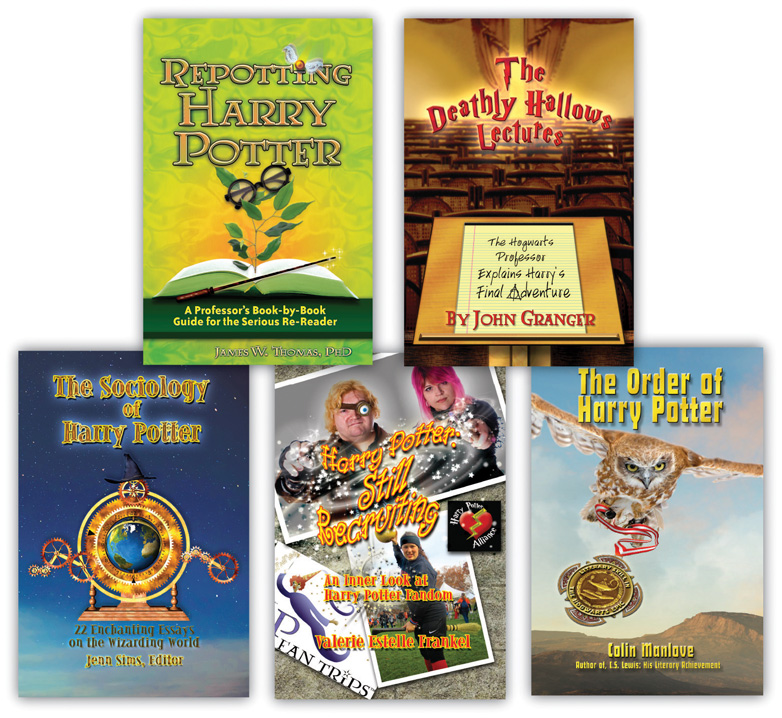

One should not do battle with Dumbledore’s Army! In a follow-up email, where John admited to Emily that his critical views of Harry Potter had not really changed, he also added that he was a little disappointed that Rowling had indicated in an interview about her first novel for adults—The Casual Vacancy (2012)—that she didn’t see herself as a role model for children. Emily responded: “If it hadn’t been for getting a copy of The Sorcerer’s Stone in the 3rd grade, I may not be an English major now. I think a lot of the English majors of my generation are proof that she is a role model for children. Also, I think she must be intentionally ignoring the fact that there is a Harry Potter amusement park…how could kids not adore her?” Emily and John, interestingly, were acting as both critic and fan (or nonfan in John’s case). In other words, readers are to a degree torn between the role of being an objective critic and a subjective fan, a tension that reader-response theory can help explain. Some publishers, in fact, concentrate on critical works on Harry Potter, creating a critical industry that extolls the virtues of the Harry Potter series. Winged Lion/Zossima Press is just one example, and the titles highlight how scholarly investigation becomes fused with personal enthusiasm for the books.

Book covers courtesy of Winged Lion/Zossima Press.

But there’s a flip side to the “positive” reading experience, too. How many times have you become so irritated by a work—or by a piece of criticism!—that you failed to finish it or dreaded every second while you were between the pages? Some may never develop a “taste” for Henry James, for example. And as much as you might admire Moby-Dick (1851) by Herman Melville, you must admit that the so-called cetological center does tax a reader’s patience.

Your Process

- List your three favorite works of literature and write a short paragraph for each explaining why you like them so much.

- Now do the same for your three least favorite works. Why do you dislike them?

- Do you notice any patterns in the works you like and dislike? Why do you suppose you feel the way you do about these works?

- Are there any works that you disliked upon initial reading but grew to like later? Or works you initially loved but now find tiring? Explain.

- Choose either one of the likes or dislikes and consider using the work as the text for your reader-response paper. The following are some key guiding questions you can ask after reading the overview of the types of reader-response theory: Why do I like or dislike this work so much? How do I read this work in a way that might explain my attitude toward the work? Does the work touch on—or challenge—my identity theme? Does my reading connect to an interpretive community? Does my gender, race, class, sexual orientation, or another aspect of my identity have anything to do with my response?

Class Process

- List your favorite literary works that you read primarily as a fan.

- Does this fan favorite hold up to critical scrutiny? Why or why not?

- How do you negotiate this tension between being a fan and a critic?

- Have your instructor list these fan favorites on the board.

- Discuss the tension between fan and critic using these examples.

- Choose either one of the likes or dislikes you listed and consider using the work as the text for your reader-response essay. The following are some key guiding questions you can ask after reading the overview of the types of reader-response theory: Why do I like or dislike this work so much? How do I read this work in a way that may explain my attitude toward the work? Does the work touch on—or challenge—my identity theme? Does my reading connect to an interpretive community? Does my gender, race, class, sexual orientation, or another aspect of my identity have anything to do with my response?

Now that we have acknowledged the fact that personal responses are an important component to the reading process—and to all literary discussion—we can begin learning about the variety of reader responses. As a New Critic, you remember, you scrutinized the text carefully; as a reader-response critic you will discover how your personal likes and dislikes shape your interpretation of a work.

6.3 Focus on Reader-Response Strategies

Reader-response strategies can be categorized, according to Richard Beach in A Teacher’s Introduction to Reader-Response Theories (1993), into five types: textualCritical approach that emphasizes the text itself (relative to other forms of reader-response criticism); the text directs interpretation as the reader directs the text to interpretation., experientialForm of criticism that emphasizes the reader’s reading process over the text; it involves analyzing our subjective responses to literature., psychologicalApproach that explores how we connect to texts on a personal level. Subjective analysis and identity analysis are subcategories of this approach., socialForm of literary criticism that explores how readers’ attitudes toward a text change over time., and culturalType of criticism that focuses on the various personal backgrounds that readers bring to a text and how these backgrounds shape the readers’ interpretations..Richard Beach, A Teacher’s Introduction to Reader-Response Theories (Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1993). Let’s review those categories.

Textual Reader-Response Strategies

Performing a close reading of a text teaches you to look “closely” at the way a text operates and to glean some meaning from the workings of the text. In other words, your interpretation is primarily directed by the text. Textual reader-response approaches admit to the fact that the text does influence the way readers read and construct meaning. Thus the reader and text interact in the process of formulating a meaning of the text. Imagine a text as a painting in an art gallery: your interpretation of the painting will be based on whether you like it or not, but this reaction will be directed by the painting itself. Or consider a literary text as a musical composition; as a listener, you are moved by the music, but you must relate the music to some experience to make it work emotionally on you. Another metaphor: a text is like an unfinished sculpture; the reader must bring the finished form to the work. Thus to textual reader-response critics, the text directs interpretation as the reader directs the text to interpretation.

Literature as Transaction: Gap Filling and Ghost Chapters

A pioneer in reader-response criticism is Louise Rosenblatt, whose Literature as Exploration (5th ed., 1995) provided an alternative theory to the persistent New Critical approaches that gained such popularity. Rosenblatt contends that literature must become personal for it to have its full impact on the reader;Louise Rosenblatt, Literature as Exploration, 5th ed. (New York: Modern Language Association, 1995). in fact, New Criticism’s affective fallacy prevents the reader from engaging the text on any personal level. Rosenblatt’s approach, like the New Critical reading methods, provides a classroom strategy; however, whereas the New Critics centered on the literary text, Rosenblatt centers on the reader.

Rosenblatt believes readers transact with the text by bringing in their past life experiences to help interpret the text.Louise Rosenblatt, Literature as Exploration, 5th ed. (New York: Modern Language Association, 1995). Reading literature becomes an event—the reader activates the work through reading. Rosenblatt argues that any literary text allows for an efferent readingWhat the reader believes he or she should retain after reading a text., which is what the reader believes should be retained after the reading; the aesthetic readingWhat the reader actually experiences while reading a text (in contrast to the efferent reading)., on the other hand, is what the reader experiences while reading.Louise Rosenblatt, Literature as Exploration, 5th ed. (New York: Modern Language Association, 1995). The aesthetic reading accounts for the changes in a reader’s attitude toward a literary work. Rosenblatt’s theory provides for a process of reading that leads to discussion and interpretation: a reader transacts with a literary text during the reading process, focusing on the aesthetic response while reading. After reading, then, the reader reflects on the aesthetic response and compares it to the textual evidence and other interpretations. In a way, literary interpretation is more focused on the transaction—the process of reading—than on an interpretation of a particular work.

Another important reader-response theorist is Wolfgang Iser, who complements Rosenblatt. Iser believes that a literary work has meaning once a reader engages in the text.Wolfgang Iser, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Text, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1979). According to Iser, every literary work is balanced by two poles, the artisticWhat the author creates; a literary work is caught between this and the esthetic pole. and the esthetic polesThat which is realized or completed by the reader; a literary work is caught between this and the artistic pole., roughly corresponding to Rosenblatt’s efferent and aesthetic readings. For Iser, the artistic pole is that created by the author; the esthetic pole is that realized or completed by the reader.Wolfgang Iser, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Text, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1979). Since a literary work is caught between these two poles, its meaning resides in the gap between these poles; the primary quality of a text is its indeterminacy. A textual critic, Iser recognizes that the text—the artistic pole—guides the reader who resides in the esthetic pole. He distinguishes between the implied readerThe reader a text creates for itself—the hypothetical person the work seems to address., one the text creates for itself, and the actual readerThe real person who reads the literary work; he or she may not resemble the text’s implied reader., the reader who brings “things” to the text.Wolfgang Iser, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Text, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1979). Consequently, there exists a gap between the implied and actual reader, and between the artistic and esthetic poles. The reader, then, must perform gap filling to concretize the text. Umberto Eco, another reader-response critic, takes gap filling even further, arguing that readers write ghost chapters for texts as a way to understand the transaction that happens between the text and reader.Umberto Eco, “The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach.” in Reader-Response Criticism from Formalism to Post-Structuralism. ed by Jane P. Tompkins. (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980) pgs. 50–69.

As you can see, Iser’s textual reader-response criticism is based on his contention that the reader concretizes the text—gives it meaning—while the text necessarily guides this concretization. Consequently, a literary text operates by indeterminacy; it has gaps that the reader attempts to fill.

Transaction: The Rhetoric of Fiction

Another pioneer in reader-response criticism is Wayne Booth, who in The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961; revised edition 1983) analyzes the way literature engages us through its language, or rhetoric.Wayne Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983). Booth shows readers how authors manipulate them into seeing things they have never seen before. Booth’s most important contributions to reader-response criticism (and literary criticism in general) are his concepts of the implied author (or narrator) and the unreliable narrator, and how these force us to confront reading as an ethical act.

The implied authorThe narrative voice an author creates in his or her work. The implied author guides or directs the reader’s interpretation of the text.—the narrative voice the author creates in a work—is the most important artistic effect: in a sense, the implied author directs the reader’s reaction to the literary work, guiding—or sometimes forcing—the reader to react on an emotional level since the implied author brings his or her ethical principles to the text. By directing the reader’s interpretation, the implied author limits the reader’s response while forcing the reader to react to the implied author.

For example, Booth contends that the implied author in Emma recognizes that the reader must be able to empathize and like Emma; if not, the novel will fail.Wayne Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983). Thus Austen creates an implied author—the narrator—who controls our perception of Emma by creating a character the reader can empathize with, laugh at when appropriate, and condemn when needed. Since the implied author becomes like a friend and guide, we as readers can rely on the narrative voice to guide us.

Booth recognizes that while a text’s implied author may be reliable, the work may still have an unreliable narratorA narrator that cannot be trusted because he or she has a limited viewpoint (often this is a first-person narrator). An unreliable narrator forces the reader to respond to the text on a moral plane.. The narrator in Jonathan Swift’s “Modest Proposal” seems perfectly reliable and in control until we realize that his proposal to alleviate the poverty of the Ireland is to raise babies as edible delicacies!Jonathan Swift, “Modest Proposal” (London: 1729; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 2004), http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/SwiMode.html. Or think of the first-person narrators of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) or J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951).J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (London: Little, Brown, 1951). An unreliable narrator requires the author and reader to engage in a special bond whereby they acknowledge that the narrator cannot be trusted; in a way, then, the reader and author engage in a transaction by recognizing the limited view of the unreliable implied author. The unreliable narrator, ultimately, forces the reader to respond on some moral plane.

By appealing to the moral qualities of the reader, Booth provides a framework for an ethics of readingThe idea that a reader must carefully judge the ethical dimension to a work, comparing his or her personal experience and moral beliefs with the narrative. that he defines in The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction (1988). Using Rosenblatt’s distinction between the efferent and aesthetic reading, Booth argues that the reader must carry over the efferent reading into the aesthetic, for the efferent reading requires us to compare our personal experience and moral beliefs with the narrative.Wayne Booth, The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988). Since a literary work takes us over for the duration of the reading experience, an ethics of reading will require the reader to eventually judge the ethical dimension to a work. Nonce beliefsThe beliefs the narrator and reader share only during the reading of the text (in contrast to fixed norms). are the beliefs the narrator and reader embrace only during the reading. Fixed normsThe beliefs upon which a literary work depends. Unlike nonce beliefs, these are applicable to the real world outside the text. are the beliefs on which the entire literary work depends for effect but also are applicable to the real world. As an example, Booth uses Aesop’s fables, for a talking animal relates to our nonce beliefs—the talking animal is acknowledged as essential to the narrative—when the fixed norms will entail the moral that concludes the fable. Thus the nonce and fixed beliefs require a transaction between reader and work. Booth suggests that an ethics of reading becomes a two-stage process: (1) the reader must surrender fully to the reading experience and then (2) the reader must contemplate the reading experience from an ethical perspective (which depends on the reader’s own moral stance).Wayne Booth, The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988). In other words, we should keep company with the literary work and maintain an open mind until we conclude that the work might be harmful to us—or be in conflict with our moral beliefs. As you can see, Booth’s ethics of reading is determined by the reader’s moral makeup, which is dependent on a specific time and reading experience. It is open to change.

Kate Chopin’s “The Storm” (1898) is a good example of this.“Kate Chopin ‘The Storm,’” The Kate Chopin International Society, http://www.katechopin.org/the-storm.shtml. In the story, a married woman has a passionate affair one afternoon with an acquaintance who by chance comes to her house to escape a storm. Their relationship is set up in an earlier story, “At the Cadian Ball” (1892), Chopin presents the affair as a natural impulse; the ending of the story tells us that both parties are happy and content.Kate Chopin, “At the ’Cadian Ball,” in The Awakening, and Selected Stories, ed. Sandra M. Gilbert (New York: Penguin, 1984). While in the company of “The Storm,” you will respond to the story itself as it occupies you, yet after your reading you will complete the reading by bringing your ethics into play: do you reject the story because it does not condemn adultery? Do you embrace the story because of its honest depiction of sexual passion?

Booth’s brand of textual reader-response criticism is a valuable tool for readers since he provides a textual model of reading—the implied author who is reliable and unreliable—that embraces the ethical dimension of the reader, who must transact with the literary work.

Textual reader-response criticism, as exemplified by Rosenblatt, Booth, and Iser, is a powerful literary critical tool to use when analyzing texts. Using some conventions of New Criticism, these critics are able to show how text and reader can simultaneously be active during the reading process.

Your Process

- Read the following fable by Aesop:

The Hare and the Tortoise

The Hare was once boasting of his speed before the other animals. “I have never yet been beaten,” said he, “when I put forth my full speed. I challenge any one here to race with me.”

The Tortoise said quietly, “I accept your challenge.”

“That is a good joke,” said the Hare; “I could dance round you all the way.”

“Keep your boasting till you’ve beaten,” answered the Tortoise. “Shall we race?”

So a course was fixed and a start was made. The Hare darted almost out of sight at once, but soon stopped and, to show his contempt for the Tortoise, lay down to have a nap. The Tortoise plodded on and plodded on, and when the Hare awoke from his nap, he saw the Tortoise just near the winning-post and could not run up in time to save the race. Then said the Tortoise: “Plodding wins the race.”Aesop, “The Hare and the Tortoise,” Aesop’s Fables, http://www.aesops-fables.org.uk/aesop-fable-the-hare-and-the-tortoise.htm.

- Use Booth’s notions of fixed and nonce beliefs to examine how you will respond to the moral of the fable. Does plodding win the race in your value system?

- Are there gaps in the narrative that you filled in to make sense of the narrative? What were they? Can you apply Rosenblatt’s and Iser’s notions of how readers complete the text?

Experiential Reader Response

Experiential reader-response critics like Stanley Fish are unlike the textual reader-response critics in one very important aspect—they emphasize the reader’s reading process over the literary work. Fish calls this kind of reader response affective stylisticsA form of experiential reader-response criticism in which readers first surrender themselves to the text, then concentrate on their reading responses while reading, and ultimately describe the reading experience by structuring their reading responses., reminding us of the “affect” that literature has on us and of the New Critical affective fallacy that rejected any emotional response a reader might have to a literary work.Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). To Fish, then, affective stylistics is the experience the reader has while reading, which he defines as a three-fold process:

- Readers surrender themselves to the text, letting the text wash over them; in fact, at this stage, readers should not be concerned with trying to understand what the work is about.

- Readers next concentrate on their reading responses while reading, seeing how each word, each sentence, each paragraph elicits a response.

- Finally, readers should describe the reading experience by structuring their reading responses, which may be in conflict with the common interpretation of a work.Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

Fish’s thesis is seductive, for when we read, we are constantly reacting to our reading, connecting it to our personal lives, to other literary works we have read, and to our reading experience at that particular reading moment. Sometimes we will love to read; other times we dread it. In Surprised by Sin, Fish examines how the reader is affected by a reading of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), that epic poem that describes the fall of Adam and Eve.John Milton, Paradise Lost (1667; University of Virginia Electronic Text Center, 1993), http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/MilPL67.html. Fish argues that the reading experience of Paradise Lost mirrors the actual Fall of Adam and Eve from the Garden.Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

As intriguing as Fish’s affective stylistics may be, the reality is that readers often agree on meaning; that is, they tend to see similar things in the same text. A textual reader-response critic would argue that the text—through its transaction with the reader—leads to such common interpretation, but Fish is interested in another possibility—that we are trained to find similar meanings. He calls this idea interpretive communitiesA group of readers who share common beliefs that cause them to read a text in a similar way. For example, feminist critics are trained to identify and analyze gender issues, so it’s likely that two feminist critics who read the same text will have similar interpretations.. To Fish, then, a reader of an interpretive community brings a meaning to the text because he or she is trained to.Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998). A student in a modernist poetry class, for example, would interpret Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar” in terms of modernism and the poetic movements in modernism and be at ease making claims about the poem’s meaning. Literary theory, which you are learning as you work your way through this text, also demonstrates the interpretive community. If you are intrigued by Freudian psychoanalytic criticism, you will find Freudian meanings in the works that you are reading; likewise, a feminist critic will find gender issues when reading. Another way to understand interpretive communities is to note that the American legal system has embraced the idea of interpretive communities in jury selection: for example, if a defense attorney who is representing a college student in an underage drinking case can get members on the jury who agree that the drinking age should be lowered to nineteen, then the jury may have already interpreted the evidence in light of their beliefs and will find the student not guilty.

Experiential reader response acknowledges that reading is a subjective process and attempts to understand how to analyze such subjective responses.

Sonnet 127

In the old age black was not counted fair,

Or if it were, it bore not beauty’s name;

But now is black beauty’s successive heir,

And beauty slandered with a bastard shame:

For since each hand hath put on Nature’s power,

Fairing the foul with Art’s false borrowed face,

Sweet beauty hath no name, no holy bower,

But is profaned, if not lives in disgrace.

Therefore my mistress’ eyes are raven black,

Her eyes so suited, and they mourners seem

At such who, not born fair, no beauty lack,

Sland’ring creation with a false esteem:

Yet so they mourn becoming of their woe,

That every tongue says beauty should look so.

Your Process

- Read the Sonnet 127 from Shakespeare.William Shakespeare, “Sonnet 127,” in Sonnets (1609; University of Virginia Electronic Text Center, 1992), http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/ShaSonQ.html. As you read, jot down what is going on in your mind. Do you try to make sense of the poem while reading? Do you become frustrated while reading? Do certain words evoke feelings?

- Have you read other sonnets by Shakespeare? If so, what do you remember about them? Did you bring your knowledge of the sonnets to the reading of this one? Did you read the poem coming from a particular interpretive community?

- How did your interpretive community shape your interpretation of the poem? What ideas from your community did you bring in interpreting the poem?

Psychological Reader Response

When we read, we are continually connecting the text to our lives, almost as if the literary work is speaking to us personally. Psychological reader response helps us better understand this phenomenon.

Subjective Analysis

Often called subjective criticismA form of reader-response criticism that views a literary work as comprising both the concrete text and our interpretation of it. The text’s meaning is ultimately created when readers compare their responses with each other to develop a communal interpretation., this form of reader-response criticism is championed by David Bleich, who believes that a reader’s response becomes the text itself, ripe for analysis (or psychoanalysis). To Bleich, a literary text comprises a real entity—the text, the words on the page, which is a concrete object—and our interpretation of the concrete text, which can be seen as a symbolic object. We “resymbolize” the text through our perceptions and beliefs. Meaning, then, is negotiated: our reading response (highly personal) is often brought to a larger body (communal) to discuss the meaning of a piece of literature. The classroom is a perfect example: you are assigned to read something, you read it and develop a personal interpretation, and then you share that interpretation with the class; ultimately, the class creates a more communal interpretation. In subjective criticism, knowledge is seen as socially constructed from the interaction of all readers; thus, interpretation is seen as personal, yet communal, the common element being that reading is subjective. The transaction that happens in subjective criticism is between the personal reader-oriented response statement and the more public-oriented response statement, which reflects the themes in the text.

Subjective criticism focuses on the negotiation for meaning—your view is not wrong if it is based on some objective reading of the text.

Identity Analysis

Norman Holland’s approach to reader response follows in the footsteps of subjective criticism. According to Holland, people deal with texts the same way they deal with life. Holland would say that we gravitate toward particular literary works because they speak to our inner—our psychological—needs. In other words, each reader has an identity that we can analyze, which will open up the literary text to personal interpretation based on a reader’s identity. Thus we use the term “identity analysisA form of psychological reader-response criticism; it posits that we are drawn to literary works that speak to our psychological needs—and, conversely, we are repelled or troubled by works that do not meet our needs.” to describe the form of psychological reader-response criticism that suggests that we are drawn to literary works that speak to our psychological needs—conversely, we are repelled or troubled by works that do not meet our needs.

These identity needs are often repressed in the unconscious and are in need of an outlet, which is provided by reading. When reading, then, we can engage our repressed desires or needs. Why do we read fantasy literature? Romance literature? Thrillers? Self-help books? Science fiction? Reading becomes a personal way to cope with life.

This coping process is interpretation, for literature exposes more about the reader than about the text itself. Holland believes that each reader has an “identity themeWithin identity analysis, the particular pattern of defense that a reader brings to a text. A reader who belongs to a marginalized racial or ethnic group, for example, is likely to have a different set of literary likes, dislikes, and defenses than a reader who belongs to the dominant racial or ethnic group in a society.,” a pattern of defense that he or she brings to a text. In turn, we gravitate to texts that tend to reinforce our identity themes and our needs. The contrary is also true: we will avoid texts that challenge our identity or threaten our psychological needs. When we read a text, we see ourselves reflected back at us. Holland calls this transactional process DEFTCritic Norman Holland’s process for reading a text, which involves defense, expectation, fantasy, and transformation.: we read in defense (a coping strategy that aligns with our expectations) that leads to fantasy (our ability to find gratification) and finally to transformation (that leads to a total unifying effect for the reader).

Your Process

- List the literary works that you have read multiple times.

- Why do you return to these works?

- Do they reflect issues that connect to your life? Can you venture to define your identity theme?

- Are there literary works you dislike? Why? Do these dislikes have anything to do with your identity theme?

Social Reader Response

Often referred to as “reception theory,” social reader response is interested in how a literary work is received over time. In fact, the status of a literary work is dependent on the reader’s reception of the work. Hans Robert Jauss, a key figure in “reception theory,” argues that the history of the reader is as important as the history of the literary work; in fact, the reader’s evolving interpretation is at the heart of the changing literary status.Hans Robert Jauss, Toward an Aesthetic Reception. Tans. Timothy Baht. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982). To Jauss, every literary work continually evolves as the reader’s reception modifies according to the reader’s needs.

A classic example from nineteenth-century American literature is Moby-Dick (1851), now considered one of the greatest—if not the greatest—American novel ever written.Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, or, The Whale (1952; University of Virginia Electronic Text Center, 1993), http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Mel2Mob.html. Andrew Delbanco titles the first chapter of his book Required Reading: Why Our American Classics Matter Now (1997) “Melville’s Sacramental Style,” which brings an almost religious fervor to the importance of Melville generally and Moby-Dick specifically.Andrew Delbanco, Required Reading: Why Our American Classics Matter Now (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1997). But this has not always been the case. Contemporary reviews of Moby-Dick were mixed, but many were quite unfavorable; these tainted Melville’s reputation and made it difficult for him to continue as a successful author. Melville.org has compiled a collection of contemporary reviews, one of which we reprint here:

Thrice unlucky Herman Melville!…

This is an odd book, professing to be a novel; wantonly eccentric; outrageously bombastic; in places charmingly and vividly descriptive. The author has read up laboriously to make a show of cetalogical [sic] learning…Herman Melville is wise in this sort of wisdom. He uses it as stuffing to fill out his skeleton story. Bad stuffing it makes, serving only to try the patience of his readers, and to tempt them to wish both him and his whales at the bottom of an unfathomable sea…

The story of this novel scarcely deserves the name…Mr. Melville cannot do without savages so he makes half of his dramatis personae wild Indians, Malays, and other untamed humanities… What the author’s original intention in spinning his preposterous yarn was, it is impossible to guess; evidently, when we compare the first and third volumes, it was never carried out…

Having said so much that may be interpreted as a censure, it is right that we should add a word of praise where deserved. There are sketches of scenes at sea, of whaling adventures, storms, and ship-life, equal to any we have ever met with…

Mr. Herman Melville has earned a deservedly high reputation for his performances in descriptive fiction. He has gathered his own materials, and travelled along fresh and untrodden literary paths, exhibiting powers of no common order, and great originality. The more careful, therefore, should he be to maintain the fame he so rapidly acquired, and not waste his strength on such purposeless and unequal doings as these rambling volumes about spermaceti whales. [ellipses in original]“Contemporary Criticism and Reviews,” The Life and Works of Herman Melville, http://www.melville.org/hmmoby.htm#Contemporary.

—London Literary Gazette, December 6, 1851

Many critics felt that Moby-Dick was a falling off of Melville’s talent, and that view remained for the rest of Melville’s life.

Why the change in reputation? Critics started reassessing Moby-Dick, scholars tell us, in 1919, and by 1930 the novel was frequently taught in college classrooms, thus cementing its critical reputation. In 1941 F. O. Mathiessen, in American Renaissance, placed Melville as a central writer in the nineteenth century.F. O. Mathieson, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1941). In addition, the rise of literary theory that focused on race, class, and gender led to new revisionist readings of Melville; more recently, queer theory has argued that Moby-Dick is a central text in gay and lesbian literature.

Another example is Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937).Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (New York: HarperCollins, 1998). Hurston was a popular author in America, but contemporary writers like Richard Wright and Langston Hughes were critical of Their Eyes Were Watching God because it seemed far away from the “protest fiction” other African American writers (mainly men) were publishing. Here is an excerpt from Richard Wright:

Miss Hurston seems to have no desire whatever to move in the direction of serious fiction… [ellipses in original]

Their Eyes Were Watching God is the story of Zora Neale Hurston’s Janie who, at sixteen, married a grubbing farmer at the anxious instigation of her slave-born grandmother. The romantic Janie, in the highly-charged language of Miss Hurston, longed to be a pear tree in blossom and have a “dust-bearing bee sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-calyxes arch to meet the love embrace.” Restless, she fled from her farmer husband and married Jody, an up-and-coming Negro business man who, in the end, proved to be no better than her first husband. After twenty years of clerking for her self-made Jody, Janie found herself a frustrated widow of forty with a small fortune on her hands. Tea Cake, “from in and through Georgia,” drifted along and, despite his youth, Janie took him. For more than two years they lived happily; but Tea Cake was bitten by a mad dog and was infected with rabies. One night in a canine rage Tea Cake tried to murder Janie, thereby forcing her to shoot the only man she had ever loved.

Miss Hurston can write, but her prose is cloaked in that facile sensuality that has dogged Negro expression since the days of Phillis Wheatley. Her dialogue manages to catch the psychological movements of the Negro folk-mind in their pure simplicity, but that’s as far as it goes.

Miss Hurston voluntarily continues in her novel the tradition which was forced upon the Negro in the theatre, that is, the minstrel technique that makes the “white folks” laugh. Her characters eat and laugh and cry and work and kill; they swing like a pendulum eternally in that safe and narrow orbit in which America likes to see the Negro live: between laughter and tears.“Their Eyes Are Watching Their Eyes Were Watching God,” University of Virginia, http://people.virginia.edu/~sfr/enam854/summer/hurston.html.

Thanks to these unfavorable reviews, Their Eyes Were Watching God became a forgotten text, and it remained so until Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple and many other works, wrote an essay in Ms. Magazine, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” that recounts her search for Hurston’s grave in Eatonville, Florida. Walker eventually bought a grave marker for Hurston’s grave, which reflects the beginning of Hurston’s reputation as a great American novelist.Alice Walker, “Finding Zora,” Ms. Magazine, March 1975, 74–75. Now Their Eyes Were Watching God and Hurston are featured in Delbanco’s study on the American classics.

Class Project: Reception Review

- Choose a popular literary text. The New York Times Best Seller List is a great place to start.

- Find three reviews of that work. You can find reviews by using a search engine—Google, for example—and if your library has Book Review Digest or Book Review Index, these are important databases.

- Write a short paper that briefly summarizes each review and then comment on the reviews. Do the reviewers agree on the book in their reviews? If not, explore the differences.

Cultural Reader Response

Cultural reader response acknowledges that readers will bring their personal background to the reading of a text. What is that background? A variety of markers, including gender, race, sexual orientation, even political affiliation compose someone’s background. In other words, as readers we may interpret a literary work in light of where we are situated in society.

For example, gender is key to the way that readers respond to a literary work. See Amy Ferdinandt’s response to James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” later in the chapter. Do men and women read differently? Some may say, “Yes.” An important text to highlight women’s reading experiences is Janice Radway’s Reading the Romance (1984).Jane Radway, Reading the Romance, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991). Radway examines why women readers gravitate to the romance novel. Radway’s ideas, for example, could be applied to Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series, a romance series about a young woman, Bella Swan, who falls in love with a vampire, Edward Cullen, but who is also attracted to a werewolf, Jacob Black.Stephenie Meyer, The Twilight Saga Collection (London: Little, Brown, 2009). The target audience for Twilight is adolescent girls, and it is unusual for boys to read Twilight. Why? Harry Potter, on the other hand, appeals to both male and female readers, as does Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games trilogy.Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games Trilogy (New York: Scholastic, 2010). Another useful text to look at is Gender and Reading: Essays on Readers, Texts and Contexts (1986), edited by Elizabeth A. Flynn and Patrocinio P. Schweickart.Elizabeth A. Flynn and Patrocinio P. Schweickart, eds., Gender and Reading: Essays on Readers, Texts, and Contexts (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

Another example to highlight culture and reading can be seen in Alan Gribben’s NewSouth edition of Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn (2011). This controversial edition replaces the “n-word” in Huckleberry Finn with the word slave; in Tom Sawyer, Gribben eliminates any derogatory language that refers to Native Americans and replaces Twain’s use of “half-breed” to, as Gribben writes, “‘half-blood,’ which is less disrespectful and has even taken on a degree of panache since J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2005).”Mark Twain, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn: The NewSouth Edition, ed. Alan Gribben (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth, 2011); J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (New York: Scholastic, 2005). Gribben acknowledges that Twain’s language can be seen as derogatory toward ethnic groups, which might preclude them from reading the texts.Mark Twain, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn: The NewSouth Edition, ed. Alan Gribben (Montgomery, AL: NewSouth, 2011). Critics argue that changing one word for another, as in Huckleberry Finn, doesn’t address the complexity of race issues in Twain. For a fascinating discussion of race regarding Twain, see the Bedford’s Case Study in Critical Controversy edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (second ed., 2004), edited by Gerald Graff and James Phelan. In the unit on race, the editors provide a variety of interpretations of Twain’s use of the “n-word,” which highlights the complexity of race in reading.Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: A Case Study in Critical Controversy, 2nd ed., ed. Gerald Graff and James Phelan (Boston: Bedford, 2003).

As you can see, cultural reader response takes seriously how a literary work might evoke a particular response from a reader based on his or her gender, race, class status, sexual orientation, and so forth, and how a reader might bring a reading strategy based on his or her identity.

Your Process

- Write a journal or blog entry that explores your cultural position as a reader.

- Does your gender, race, religion, politics, sexual orientation, and/or another cultural marker partly determine what you read and how you read literary works? Give at least two concrete examples.

6.4 Reader Response: A Process Approach

Reader response is a powerful literary method that is refreshing since it allows you to concentrate on yourself as a reader specifically or on readers generally.

- Carefully read the work you will analyze.

- Formulate a general question after your initial reading that identifies a problem—a tension—that is fruitful for discussion and that.

- Reread the work, paying particular attention to the question you posed. Take notes, which should be focused on your central question. Write an exploratory journal entry or blog post that allows you to play with ideas.

-

Construct a working thesis that makes a claim about the work and accounts for the following:

- What does the work mean?

- How does reader-response theory add meaning?

- “So what” is significant about the work? That is, why is it important for you to write about this work? What will readers learn from reading your interpretation?

- Reread the text to gather textual evidence for support. What literary devices are used to achieve the theme?

- Construct an informal outline that demonstrates how you will support your interpretation.

- Write a first draft.

- Receive feedback from peers and your instructor via peer review and conferencing with your instructor (if possible).

- Revise the paper, which will include revising your original thesis statement and restructuring your paper to best support the thesis. Note: You probably will revise many times, so it is important to receive feedback at every draft stage if possible.

- Edit and proofread for correctness, clarity, and style.

We recommend that you follow this process for every paper that you write from this textbook. Of course, these steps can be modified to fit your writing process, but the plan does ensure that you will engage in a thorough reading of the text as you work through the writing process, which demands that you allow plenty of time for reading, reflecting, writing, reviewing, and revising.

6.5 Student Writer at Work: Amy Ferdinandt’s Reader Response to James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”

Amy had read Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” numerous times in high school and was convinced that it was a comical story about a husband and wife. She was somewhat surprised to see the story reprinted again in her college textbook, which reminded her that the story is central to the American literary canon. If you haven’t read the story, you can do so at the Zoetrope: All-Story website.James Thurber, “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” Zoetrope: All-Story 5, no. 1 (2001), http://www.all-story.com/issues.cgi?action=show_story&story_id=100.

Amy’s Process

Since Amy was in search of a story to do a reader-response paper on, she thought she might return to a story she knew quite well. She discovered, however, that her response to the story was quite different than it had been when she read it in high school. In fact, she realized that the story now irritated her. Her goal in the paper was to examine why she had this shift in interpretation of the story.

Amy had just taken a Shakespeare course where they learned about the Renaissance notions of women and men. They studied Ian MacLean’s The Renaissance Notion of Woman, which provides a binary chart of the perceived differences between men and women:Ian MacLean, The Renaissance Notion of Woman (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

| Men | Women |

|---|---|

| limit | unlimited |

| odd | even |

| one | plurality |

| right | left |

| square | oblong |

| at rest | moving |

| straight | curved |

| light | darkness |

| good | evil |

Amy also added to the list other binaries that she had encountered in discussions in other college classes, many outside of English literature:

| Husband | Wife |

|---|---|

| father | mother |

| reason | emotion |

| strong | weak |

| active | passive |

| public | domestic |

Such a chart, of course, suggests that one category is privileged over another: reason over emotion, good over evil, light over darkness, active over passive, strong over weak, and husband over wife. In other words, men over women. And Amy realized that the humor in Thurber’s essay results because he inverts these binaries, because Mrs. Mitty becomes a stereotypical nagging wife and seems to take on the active male role, while Walter becomes passive, more in line with another stereotype that is placed upon a woman. Now Amy was in a bind: as a female reader, how was she to find humor in such stereotypes of men and women?

Amy’s paper blends textual and cultural reader-response theory—the use of gap filling with the notion that gender influences reading strategies. The first draft of Amy’s paper begins with a journal entry that she wrote to generate ideas for her paper:

It is certain that women misread “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” I did. I found myself initially wishing that Mrs. Mitty would just let Walter daydream in peace. But after reading the story again and paying attention to the portrayal of Mrs. Mitty, I realized that it is imperative that women rebel against the texts that would oppress them. By misreading a text, the woman reader understands it in a way that is conventional and acceptable to the literary world. But in so doing, she is also distancing herself from the text, not fully embracing it or its meaning in her life. By rebelling against the text, the female reader not only has to understand the point of view of the author and the male audience, but she also has to formulate her own opinions and create a sort of dialogue between the text and herself. Rebelling against the text and the stereotypes encourages an active dialogue between the woman and the text which, in turn, guarantees an active and (most likely) angry reader response. I became a resisting reader.

That paragraph, as you will see, becomes the final paragraph in the finished paper. Amy decided to bring the personal—her impassioned plea—in at the end and allow the more theoretical and objective discussion to drive the paper, thereby making the personal plea at the end more profound and possibly more persuasive.

As a side note, if you think Amy may protest too much in her paper, you might want to read another popular story by Thurber, “The Unicorn in the Garden” (http://english.glendale.cc.ca.us/unicorn1.html).James Thurber, “The Unicorn in the Garden,” Glendale Community College, http://english.glendale.cc.ca.us/unicorn1.html.

Is Amy on to something in her paper?

Final Draft

Amy Ferdinandt

Professor Pennington

Introduction to Literature

24 April 20–

To Misread or to Rebel: A Woman’s Reading of “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”

At its simplest, reading is “an activity that is guided by the text; this must be processed by the reader who is then, in turn, affected by what he has processed” (Iser 63). The text is the compass and map, the reader is the explorer. However, the explorer cannot disregard those unexpected boulders in the path which he or she encounters along the journey that are not written on the map. Likewise, the woman reader does not come to the text without outside influences. She comes with her experiences as a woman—a professional woman, a divorcée, a single mother. Her reading, then, is influenced by her experiences. So when she reads a piece of literature like “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” by James Thurber, which paints a highly negative picture of Mitty’s wife, the woman reader is forced to either misread the story and accept Mrs. Mitty as a domineering, mothering wife, or rebel against that picture and become angry at the society which sees her that way.

Due to pre-existing sociosexual standards, women see characters, family structures, even societal structures from the bottom as an oppressed group rather than from a powerful position on the top, as men do. As Louise Rosenblatt states: a reader’s “tendency toward identification [with characters or events] will certainly be guided by our preoccupations at the time we read. Our problems and needs may lead us to focus on those characters and situations through which we may achieve the satisfactions, the balanced vision, or perhaps merely the unequivocal motives unattained in our own lives” (38). A woman reader who feels chained by her role as a housewife is more likely to identify with an individual who is oppressed or feels trapped than the reader’s executive husband is. Likewise, a woman who is unable to have children might respond to a story of a child’s death more emotionally than a woman who does not want children. However, if the perspective of a woman does not match that of the male author whose work she is reading, a woman reader who has been shaped by a male-dominated society is forced to misread the text, reacting to the “words on the page in one way rather than another because she operates according to the same set of rules that the author used to generate them” (Tompkins xvii). By accepting the author’s perspective and reading the text as he intended, the woman reader is forced to disregard her own, female perspective. This, in turn, leads to a concept called “asymmetrical contingency,” described by Iser as that which occurs “when Partner A gives up trying to implement his own behavioral plan and without resistance follows that of Partner B. He adapts himself to and is absorbed by the behavioral strategy of B” (164). Using this argument, it becomes clear that a woman reader (Partner A) when faced with a text written by a man (Partner B) will most likely succumb to the perspective of the writer and she is thus forced to misread the text. Or, she could rebel against the text and raise an angry, feminist voice in protest.

James Thurber, in the eyes of most literary critics, is one of the foremost American humorists of the 20th century, and his short story “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” is believed to have “ushered in a major [literary] period … where the individual can maintain his self … an appropriate way of assaulting rigid forms” (Elias 432). The rigid form in Thurber’s story is Mrs. Mitty, the main character’s wife. She is portrayed by Walter Mitty as a horrible, mothering nag. As a way of escaping her constant griping, he imagines fantastic daydreams which carry him away from Mrs. Mitty’s voice. Yet she repeatedly interrupts his reveries and Mitty responds to her as though she is “grossly unfamiliar, like a strange woman who had yelled at him in the crowd” (286). Not only is his wife annoying to him, but she is also distant and removed from what he cares about, like a stranger. When she does speak to him, it seems reflective of the way a mother would speak to a child. For example, Mrs. Mitty asks, “‘Why don’t you wear your gloves? Have you lost your gloves?’ Walter Mitty reached in a pocket and brought out the gloves. He put them on, but after she had turned and gone into the building and he had driven on to a red light, he took them off again” (286). Mrs. Mitty’s care for her husband’s health is seen as nagging to Walter Mitty, and the audience is amused that he responds like a child and does the opposite of what Mrs. Mitty asked of him. Finally, the clearest way in which Mrs. Mitty is portrayed as a burdensome wife is at the end of the piece when Walter, waiting for his wife to exit the store, imagines that he is facing “the firing squad; erect and motionless, proud and disdainful, Walter Mitty the Undefeated, inscrutable to the last” (289). Not only is Mrs. Mitty portrayed as a mothering, bothersome hen, but she is ultimately described as that which will be the death of Walter Mitty.

Mrs. Mitty is a direct literary descendant of the first woman to be stereotyped as a nagging wife, Dame Van Winkle, the creation of the American writer, Washington Irving. Likewise, Walter Mitty is a reflection of his dreaming predecessor, Rip Van Winkle, who falls into a deep sleep for a hundred years and awakes to the relief of finding out that his nagging wife has died. Judith Fetterley explains in her book, The Resisting Reader, how such a portrayal of women forces a woman who reads “Rip Van Winkle” and other such stories “to find herself excluded from the experience of the story” so that she “cannot read the story without being assaulted by the negative images of women it presents” (10). The result, it seems, is for a woman reader of a story like “Rip Van Winkle” or “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” to either be excluded from the text, or accept the negative images of women the story puts forth. As Fetterley points out, “The consequence for the female reader is a divided self. She is asked to identify with Rip and against herself, to scorn the amiable sex and act just like it, to laugh at Dame Van Winkle and accept that she represents ‘woman,’ to be at once both repressor and repressed, and ultimately to realize that she is neither” (11). Thus, a woman is forced to misread the text and accept “woman as villain.” as Fetterley names it, or rebel against both the story and its message.

So how does a woman reader respond to this portrayal of Mrs. Mitty? If she were to follow Iser’s claim, she would defer to the male point of view presented by the author. She would sympathize with Mitty, as Thurber wants us to do, and see domineering women in her own life that resemble Mrs. Mitty. She may see her mother and remember all the times that she nagged her about zipping up her coat against the bitter winter wind. Or the female reader might identify Mrs. Mitty with her controlling mother-in-law and chuckle at Mitty’s attempts to escape her control, just as her husband tries to escape the criticism and control of his own mother. Iser’s ideal female reader would undoubtedly look at her own position as mother and wife and would vow to never become such a domineering person. This reader would probably also agree with a critic who says that “Mitty has a wife who embodies the authority of a society in which the husband cannot function” (Lindner 440). She could see the faults in a relationship that is too controlled by a woman and recognize that a man needs to feel important and dominant in his relationship with his wife. It could be said that the female reader would agree completely with Thurber’s portrayal of the domineering wife. The female reader could simply misread the text.

Or, the female reader could rebel against the text. She could see Mrs. Mitty as a woman who is trying to do her best to keep her husband well and cared for. She could see Walter as a man with a fleeting grip on reality who daydreams that he is a fighter pilot, a brilliant surgeon, a gun expert, or a military hero, when he actually is a poor driver with a slow reaction time to a green traffic light. The female reader could read critics of Thurber who say that by allowing his wife to dominate him, Mitty becomes a “non-hero in a civilization in which women are winning the battle of the sexes” (Hasley 533) and become angry that a woman’s fight for equality is seen merely as a battle between the sexes. She could read Walter’s daydreams as his attempt to dominate his wife, since all of his fantasies center on him in traditional roles of power. This, for most women, would cause anger at Mitty (and indirectly Thurber) for creating and promoting a society which believes that women need to stay subservient to men. From a male point of view, it becomes a battle of the sexes. In a woman’s eyes, her reading is simply a struggle for equality within the text and in the world outside that the text reflects.

It is certain that women misread “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” I did. I found myself initially wishing that Mrs. Mitty would just let Walter daydream in peace. But after reading the story again and paying attention to the portrayal of Mrs. Mitty, I realized that it is imperative that women rebel against the texts that would oppress them. By misreading a text, the woman reader understands it in a way that is conventional and acceptable to the literary world. But in so doing, she is also distancing herself from the text, not fully embracing it or its meaning in her life. By rebelling against the text, the female reader not only has to understand the point of view of the author and the male audience, but she also has to formulate her own opinions and create a sort of dialogue between the text and herself. Rebelling against the text and the stereotypes encourages an active dialogue between the woman and the text which, in turn, guarantees an active and (most likely) angry reader response. I became a resisting reader.

Works Cited

Elias, Robert H. “James Thurber: The Primitive, the Innocent, and the Individual.” Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 5. Ed. Dedria Bryfonski. Detroit: Gale Research, 1980. 431–32. Print.

Fetterley, Judith. The Resisting Reader. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1978. Print.

Hasley, Louis. “James Thurber: Artist in Humor.” Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 11. Ed. Dedria Bryfonski. Detroit: Gale Research, 1980. 532–34. Print.

Iser, Wolfgang. The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1981. Print.

Lindner, Carl M. “Thurber’s Walter Mitty—The Underground American Hero.” Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 5. Ed. Dedria Bryfonski. Detroit: Gale Research, 1980. 440–41. Print.

Rosenblatt, Louise M. Literature as Exploration. New York: MLA, 1976. Print.

Thurber, James. “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” Literature: An Introduction to Critical Reading. Ed. William Vesterman. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1993. 286–89. Print.

Tompkins, Jane P. “An Introduction to Reader-Response Criticism.” Reader Response Criticism: From Formalism to Post-Structuralism. Ed. Jane P. Tompkins. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1980. ix-xxvi. Print.

6.6 Student Sample Paper: Hannah Schmitt’s “The Death of Intellectualism in Grahame-Smith and Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies”

This chapter begins with an example from Jane Austen’s Emma. Austen has become a cultural commodity—that is, she is continually updated and revised to make her relevant to our society. On the one hand, there are the serious scholars of Austen, who analyze her work as central to the key canon of literature. On the other hand, there exists the Janeites, who are the ultimate fans of the novelist, groupies so to speak.

This tension leads to interesting updates. The 1995 movie Clueless, for example, is an updating of Emma, centering the courtship dynamics in a high school. Lost in Austen, a 2008 television series, is a kind of time-swapping story where a young Londoner of the twenty-first century changes roles with Elizabeth Bennet from Pride and Prejudice (1813).Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813; Project Gutenberg, 2008), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1342/1342-h/1342-h.htm. Karen Joy Fowler’s novel The Jane Austen Book Club (2004) concerns a book club that meets to discuss Austen; it was made into a popular movie in 2007.Karen Joy Fowler, The Jane Austen Book Club (New York: Penguin, 2004).

The most audacious reappropriating of Austen may be Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009).Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (Philadelphia: Quirk, 2009). Hannah was interested in the popularity of such an update and explores possible reasons for this popularity in the following paper, which develops its argument by engaging in reader-response criticism.

Hannah Schmitt

Professor Londo

Literature and Writing

May 22, 20–