This is “Literary Snapshot: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, section 5.1 from the book Creating Literary Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.1 Literary Snapshot: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Lewis Carroll, as we found out in previous chapters, is most famous for two books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1872). These books follow the adventures of a seven-year-old, Alice, who tumbles down a rabbit hole (Wonderland) and enters a magic mirror (Looking-Glass), entering a nonsensical world of the imagination. If you have not already read these classic books—or wish to reread them—you can access them at the following links:

http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarGlas.html

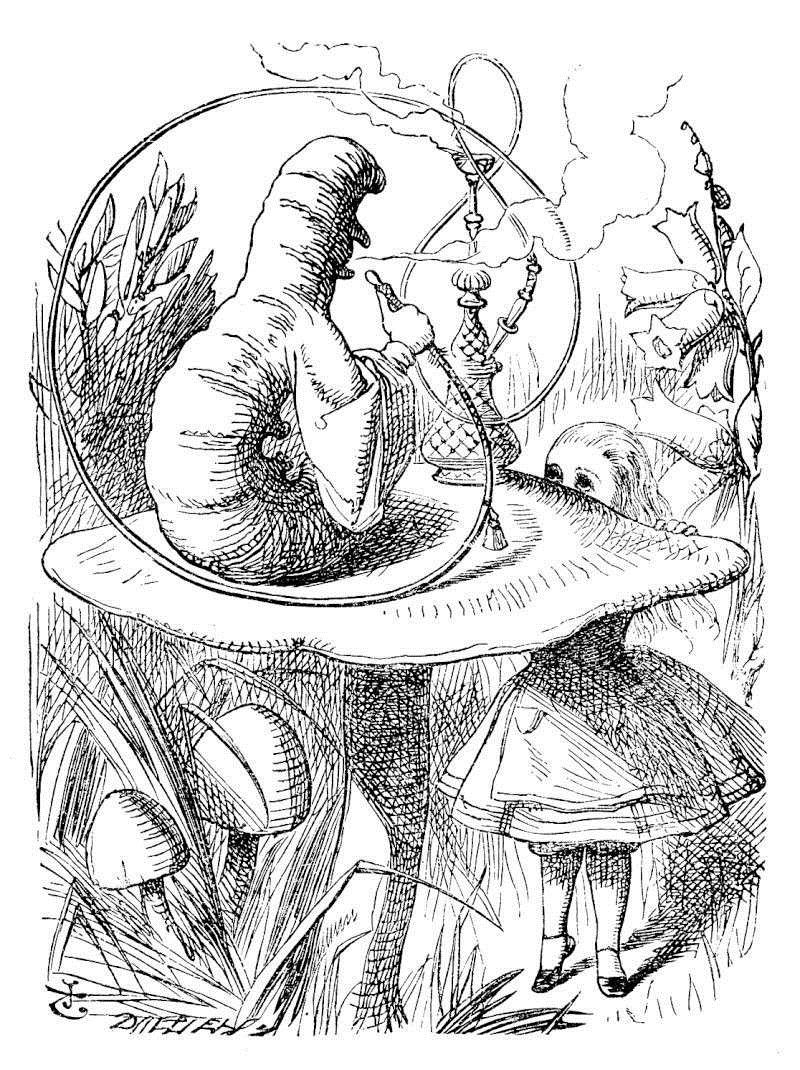

In one of the most well-known scenes from Wonderland, Alice encounters a Caterpillar sitting on top of a mushroom, “with its arms folded, quietly smoking a long hookah, and taking not the smallest notice of her or of anything else.”Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. With Forty-Two Illustrations by John Tenniel (New York: D. Appleton, 1927; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1998), chap. 4, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html. The two engage in an exchange typical of this novel: their conversation is long, confrontational, and convoluted, as each partner in the conversation fails to understand or be understood by the other:

The Caterpillar and Alice looked at each other for some time in silence: at last the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth, and addressed her in a languid, sleepy voice.

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, “I—I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

“What do you mean by that?” said the Caterpillar sternly. “Explain yourself!”

“I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, sir,” said Alice, “because I’m not myself, you see.”

“I don’t see,” said the Caterpillar.

“I’m afraid I can’t put it more clearly,” Alice replied very politely, “for I can’t understand it myself to begin with; and being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing.”

“It isn’t,” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, perhaps you haven’t found it so yet,” said Alice; “but when you have to turn into a chrysalis—you will some day, you know—and then after that into a butterfly, I should think you’ll feel it a little queer, won’t you?”

“Not a bit,” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,” said Alice; “all I know is, it would feel very queer to me.”

“You!” said the Caterpillar contemptuously. “Who are you?”

Which brought them back again to the beginning of the conversation. Alice felt a little irritated at the Caterpillar’s making such very short remarks, and she drew herself up and said, very gravely, “I think, you ought to tell me who you are, first.”

“Why?” said the Caterpillar.

Here was another puzzling question; and as Alice could not think of any good reason, and as the Caterpillar seemed to be in a very unpleasant state of mind, she turned away.

“Come back!” the Caterpillar called after her. “I’ve something important to say!”

This sounded promising, certainly: Alice turned and came back again.

“Keep your temper,” said the Caterpillar.

“Is that all?” said Alice, swallowing down her anger as well as she could.

“No,” said the Caterpillar.

Alice thought she might as well wait, as she had nothing else to do, and perhaps after all it might tell her something worth hearing. For some minutes it puffed away without speaking, but at last it unfolded its arms, took the hookah out of its mouth again, and said, “So you think you’re changed, do you?” [bold added]Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. With Forty-Two Illustrations by John Tenniel (New York: D. Appleton, 1927; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1998), chap. 5, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html.

Many readers identify closely with Alice in these scenes. They’re bewildered at the behavior of the creatures Alice encounters and, perhaps, become as frustrated as she does when the citizens of Wonderland talk in circles around her. The “puzzling questions” Alice encounters seem unanswerable, simply nonsense that Alice is right to dismiss.

However, if we think of Wonderland as a narrative of encounter—a story of different cultures colliding—we might draw more nuanced conclusions about these scenes. Could we, for instance, read such scenes from the perspective of the inhabitants of Wonderland? How might the Caterpillar think of Alice during their exchanges? Consider these paragraphs:

The Caterpillar was the first to speak.

“What size do you want to be?” it asked.

“Oh, I’m not particular as to size,” Alice hastily replied; “only one doesn’t like changing so often, you know.”

“I don’t know,” said the Caterpillar.

Alice said nothing: she had never been so much contradicted in her life before, and she felt that she was losing her temper.

“Are you content now?” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, I should like to be a little larger, sir, if you wouldn’t mind,” said Alice: “three inches is such a wretched height to be.”

“It is a very good height indeed!” said the Caterpillar angrily, rearing itself upright as it spoke (it was exactly three inches high).

“But I’m not used to it!” pleaded poor Alice in a piteous tone. And she thought of herself, “I wish the creatures wouldn’t be so easily offended!”

“You’ll get used to it in time,” said the Caterpillar; and it put the hookah into its mouth and began smoking again.Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. With Forty-Two Illustrations by John Tenniel (New York: D. Appleton, 1927; University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center, 1998), chap. 5, http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/CarAlic.html.

The Caterpillar takes offense when Alice suggests that “three inches is such a wretched height to be.” As the story points out, the Caterpillar is “exactly three inches high,” and it is angered that Alice defines the best possible height as her own height, dismissing its body as “wretched” without even considering its feelings. When Alice thinks, “I wish the creatures wouldn’t be so easily offended,” she reveals a feeling of innate superiority over the beings she encounters. Though the Caterpillar speaks with her, it is a “creature” who shouldn’t be “so easily offended” even though she directly insults it.

As we see in Chapter 4 "Writing about Gender and Sexuality: Applying Feminist and Gender Criticism", literary scholars are often interested in questions of identity in literary works. In that chapter we discuss identities drawn from gender and sexuality; in this chapter we look at identities drawn from race, ethnicity, and/or cultural background. For scholars interested in literary depictions of race and ethnicity, scenes such as the Caterpillar’s in Wonderland can be read as demonstrating problematic attitudes toward minorities within Western cultures or toward people in non-Western societies. Such problematic attitudes are particularly disconcerting when found in widely read, canonicalThe set of texts considered central to literary study: the books, poems, plays, and essays most frequently studied and taught. A canonical text, then, is a text that is frequently included in literary scholarship and in literature classes. stories such as Wonderland. Let’s look for a minute at the way the Caterpillar is depicted in the text and in early illustrations of the novel.

Illustration by Sir John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

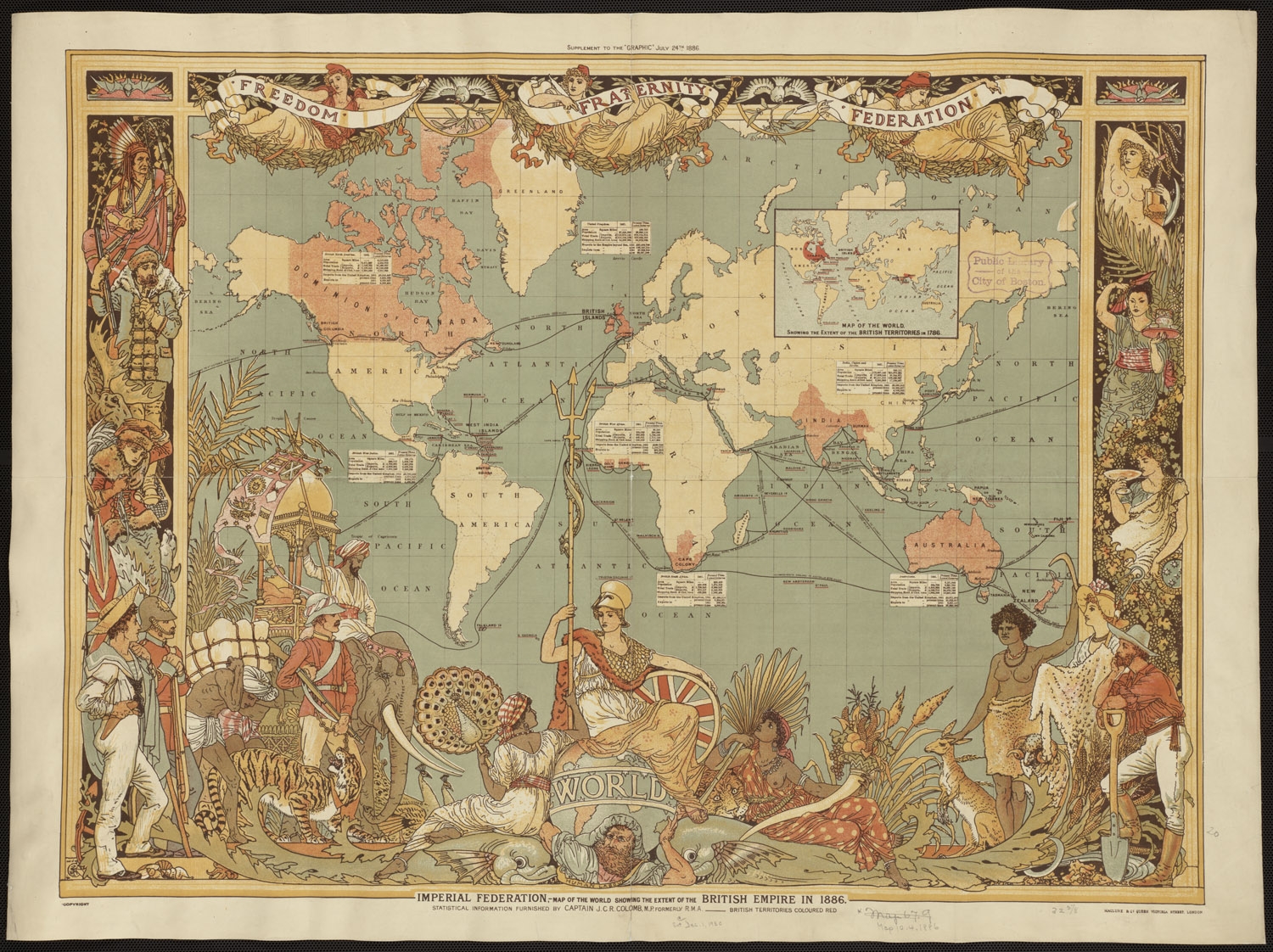

The Caterpillar is described as “quietly smoking a long hookah” and appears, from behind, almost like a thin man sitting cross-legged while smoking. Keep in mind that Wonderland was published in 1865, when the British Empire stretched around the world and was described as a “vast empire on which the sun never sets.” The British Empire in 1865 controlled territories in the Mideast and Asia, including Hong Kong, India, and Singapore. The 1860s were also, as Jon Stratton points out in Writing Sites: A Genealogy of the Postmodern World, “the major period of British exploration and colonisation (sic) of Africa.”Jon Stratton, Writing Sites: A Genealogy of the Postmodern World (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 168. You can see how far the British Empire expanded by looking at the red areas (British territories) on this map of the British Empire in 1886.

Map of the world by Captain J.C.R. Colomb and Maclure & Co. Published as a supplement for The Graphic, as the “Imperial Federation” (July, 1886).

To its original British readers, then, the Caterpillar would have evoked romanticized images of these “exotic” civilizations, smoking with a device that originated in the Middle East and would have been familiar to British citizens because of their presence in India. By contrast, Alice is drawn as the ideal of a nineteenth-century English girl, with white skin and blonde hair, knowledge of diverse academic subjects such as biology and poetry, and a heightened sense of manners and propriety.

For Stratton, Wonderland can be read as a “fantasy of civilising [sic] the natives” as Alice enters “an Other world where people behave differently,” to which she “brings her own standards and manners to bear without any reference to the local set.”Jon Stratton, Writing Sites: A Genealogy of the Postmodern World (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 170. Because Alice believes that her rules and standards are universal and should be obvious to all the people she encounters in Wonderland, she can be seen as a symbol of the British Empire, which worked to impose British standards of education, manners, religion, and politics on the people whose countries they controlled. “Were Alice to lose her place as the arbiter of meaning,” Stratton claims, “she would lose her privileged position in Wonderland,” a place where “colonial Otherness threatens the fixity of meaning by offering alternatives.”Jon Stratton, Writing Sites: A Genealogy of the Postmodern World (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 172. Like the female image of Britannia in the center of the map shown, Alice is surrounded by exotic “natives” who she expects will look to her as a model of civilization.

The Caterpillar disrupts Alice’s presumption of her own authority in Wonderland. He demands to know “Who are you?” and the question confuses and disturbs Alice. She insists, “I think, you ought to tell me who you are, first,” but when the Caterpillar asks her “Why?” she “could not think of any good reason.” Alice maintains a belief in her own superiority—a belief that she should be able to demand answers of the Caterpillar but not the other way around—but her experiences in Wonderland unsettle those beliefs. Though Alice insists that the citizens of Wonderland are strange or foreign, for the citizens of Wonderland, Alice is the stranger unfairly judging their society and its customs based on her own cultural biases and assumptions.

Interestingly, the colonialThe process by which a state conquers and governs a geographic area or another nation. In literary studies, “colonial,” “colonialist,” and related terms often describe texts that are produced during a period of colonization, either by the colonizers or by the people under colonial rule. ideas that are implicit in Carroll’s original Wonderland become explicit in the latest film adaptation of the novel, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (2010). At the end of that film, Alice (who is nineteen in Burton’s version) decides that she will help her father expand his business to China. As Kevin Slaten points out, this means that Alice will likely be involved in British-Chinese relations during the time of the Opium Wars, a pair of conflicts that decimated many areas along China’s coast and led to what Chinese historians deemed a “century of humiliation” for the nation.Kevin Slaten, “Who Else Might Be Mad at Alice? China,” Real Clear World, March 12, 2010, http://www.realclearworld.com/articles/2010/03/12/who_else_might_be_mad_at_alice_china_98853.html. In other words, Burton places Alice in China during a period of colonial aggression, perhaps signaling that Alice’s insistence on her authority over the denizens of Wonderland has prepared her to enact such authority on behalf of British trade interests in the “real world.” Tim Burton’s ending to Alice in Wonderland can be seen as a postcolonialPostcolonial theories attempt to understand and explain the cultural, intellectual, and societal legacies of colonial rule. interpretation of Lewis Carroll’s novel: a critique of the politics underlying what seems to be a simple children’s story.

Your Process

- What are some other scenes in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that might read differently if you considered the other characters’ perspectives rather than just Alice’s?

- What are some literary works that you think of as “ethnic” or “cultural”—that seem different or foreign to your own experience? Create a list in your notes. Then create a list of works that seem “normal,” or familiar to your own experience. Compare your two lists. How is your experience of literature shaped by your own cultural, ethnic, or racial background?