This is “Movement in Your Speech”, section 11.3 from the book Communication for Business Success (Canadian Edition) (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

11.3 Movement in Your Speech

Learning Objective

- Demonstrate how to use movement to increase the effectiveness of your presentation.

At some point in your business career you will be called upon to give a speech. It may be to an audience of one on a sales floor, or to a large audience at a national meeting. You already know you need to make a positive first impression, but do you know how to use movement in your presentation? In this section we’ll examine several strategies for movement and their relative advantages and disadvantages.

Customers and audiences respond well to speakers who are comfortable with themselves. Comfortable doesn’t mean overconfident or cocky, and it doesn’t mean shy or timid. It means that an audience is far more likely to forgive the occasional “umm” or “ahh,” or the nonverbal equivalent of a misstep, if the speaker is comfortable with themselves and their message.

Let’s start with behaviours to avoid. Who would you rather listen to: a speaker who moves confidently across the stage or one who hides behind the podium; one who expresses herself nonverbally with purpose and meaning, or one who crosses his arms or clings to the lectern?

Audiences are most likely to respond positively to open, dynamic speakers who convey the feeling of being at ease with their bodies. The setting, combined with audience expectations, will give a range of movement. If you are speaking at a formal event, or if you are being covered by a stationary camera, you may be expected to stay in one spot. If the stage allows you to explore, closing the distance between yourself and your audience may prove effective. Rather than focus on a list of behaviours and their relationship to environment and context, give emphasis to what your audience expects and what you yourself would find more engaging instead.

Novice speakers are often told to keep their arms at their sides, or to restrict their movement to only that which is absolutely necessary. If you are in formal training for a military presentation, or a forensics (speech and debate) competition, this may hold true. But in business and industry, “whatever works” rules the day. You can’t say that expressive gestures—common among many cultural groups, like arm movement while speaking—are not appropriate when they are, in fact, expected.

The questions are, again, what does your audience consider appropriate and what do you feel comfortable doing during your presentation? Since the emphasis is always on meeting the needs of the customer, whether it is an audience of one on a sales floor or a large national gathering, you may need to stretch outside your comfort zone. On that same note, don’t stretch too far and move yourself into the uncomfortable range. Finding balance is a challenge, but no one ever said giving a speech was easy.

Movement is an important aspect of your speech and requires planning, the same as the words you choose and the visual aids you design. Be natural, but do not naturally shuffle your feet, pace back and forth, or rock on your heels through your entire speech. These behaviours distract your audience from your message and can communicate nervousness, undermining your credibility.

Positions on the Stage

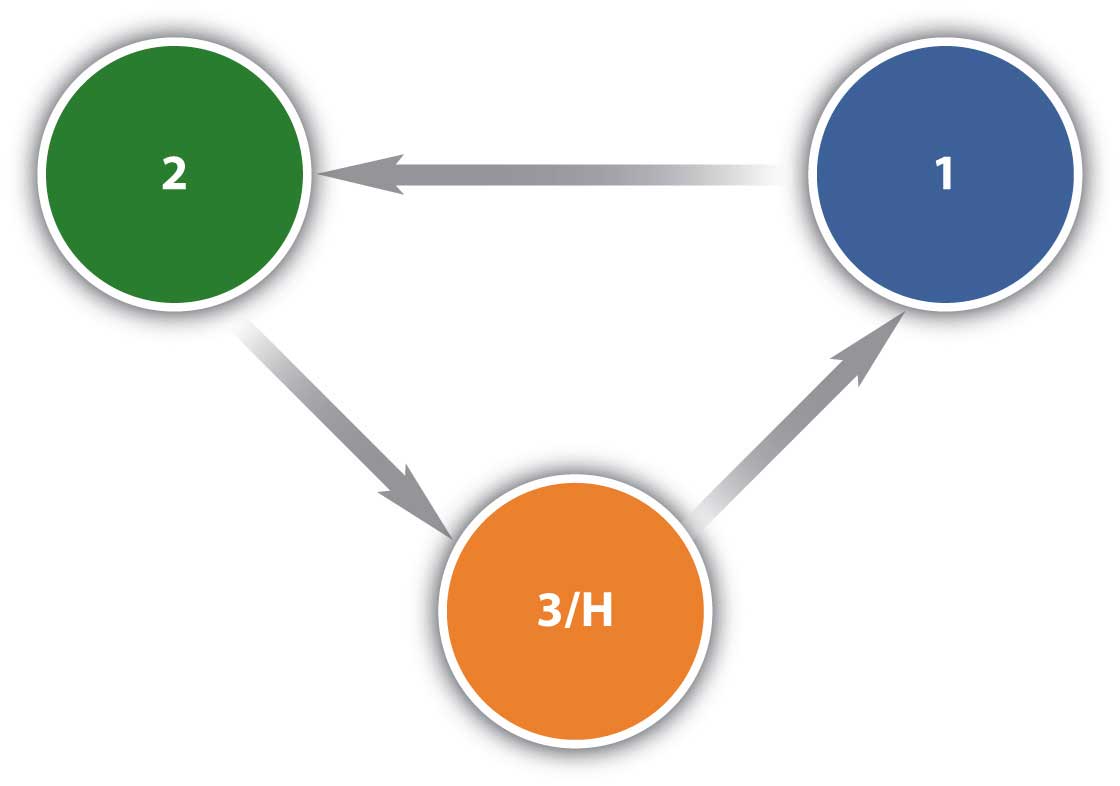

Figure 11.3 Speaker’s Triangle

In a classical speech presentation, positions on the stage serve to guide both the speaker and the audience through transitions. The speaker’s triangle (see Figure 11.3 "Speaker’s Triangle") indicates where the speaker starts in the introduction, moves to the second position for the first point, across for the second point, then returns to the original position to make the third point and conclusion. This movement technique can be quite effective to help you remember each of your main points. It allows you to break down your speech into manageable parts, and putting tape on the floor to indicate position is a common presentation trick. Your movement will demonstrate purpose and reinforce your credibility.

Gestures

Gestures involve using your arms and hands while communicating. Gestures provide a way to channel your nervous energy into a positive activity that benefits your speech and gives you something to do with your hands. For example, watch people in normal, everyday conversations. They frequently use their hands to express themselves. Do you think they think about how they use their hands? Most people do not. Their arm and hand gestures come naturally as part of their expression, often reflecting what they have learned within their community.

For professional speakers this is also true, but deliberate movement can reinforce, repeat, and even regulate an audience’s response to their verbal and nonverbal messages. You want to come across as comfortable and natural, and your use of your arms and hands contributes to your presentation. We can easily recognize that a well-chosen gesture can help make a point memorable or lead the audience to the next point.

As professional speakers lead up to a main point, they raise their hand slightly, perhaps waist high, often called an anticipation stepRaising the hand slightly to signal a nonverbal foreshadowing.. The gesture clearly shows the audience your anticipation of an upcoming point, serving as a nonverbal form of foreshadowing.

The implementation stepHolding one hand at waist level pointing outward, and raising it up with your palm forward, as in the “stop” gesture., which comes next, involves using your arms and hands above your waist. By holding one hand at waist level pointing outward, and raising it up with your palm forward, as in the “stop” gesture, you signal the point. The nonverbal gesture complements the spoken word, and as students of speech have noted across time, audiences respond to this nonverbal reinforcement. You then slowly lower your hand down past your waistline and away from your body, letting go of the gesture, and signalling your transition.

The relaxation stepLowering your hand past your waistline and away from your body., where the letting go motion complements your residual message, concludes the motion.

Facial Gestures

As you progress as a speaker from gestures and movement, you will need to turn your attention to facial gestures and expressions. Facial gesturesUsing your face to display feelings and attitudes nonverbally. involve using your face to display feelings and attitudes nonverbally. They may reinforce, or contradict, the spoken word, and their impact cannot be underestimated. As we have discussed, people often focus more on how we say something than what we actually say, and place more importance on our nonverbal gestures.Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages: Implicit communication of emotions and attitudes (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. As in other body movements, your facial gestures should come naturally, but giving them due thought and consideration can keep you aware of how you are communicating the nonverbal message.

Facial gestures should reflect the tone and emotion of your verbal communication. If you are using humour in your speech, you will likely smile and wink to complement the amusement expressed in your words. Smiling will be much less appropriate if your presentation involves a serious subject such as cancer or car accidents. Consider how you want your audience to feel in response to your message, and identify the facial gestures you can use to promote those feelings. Then practice in front of a mirror so that the gestures come naturally.

The single most important facial gesture (in mainstream Canadian and U.S. culture) is eye contact.Seiler, W., & Beall, M. (2000). Communication: Making connections (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Eye contactThe speaker’s gaze that engages the audience members. refers to the speaker’s gaze that engages the audience members. It can vary in degree and length, and in many cases, is culturally influenced. Both the speaker’s expectations and the audience member’s notion of what is appropriate will influence normative expectations for eye contact. In some cultures, there are understood behavioural expectations for male gaze directed toward females, and vice versa. In a similar way, children may have expectations of when to look their elders in the eye, and when to gaze down. Depending on the culture, both may be nonverbal signals of listening. Understanding your audience is critical when it comes to nonverbal expectations.

When giving a presentation, avoid looking over people’s heads, staring at a point on the wall, or letting your eyes dart all over the place. The audience will find these mannerisms unnerving. They will not feel as connected, or receptive, to your message and you will reduce your effectiveness. Move your eyes gradually and naturally across the audience, both close to you and toward the back of the room. Try to look for faces that look interested and engaged in your message. Do not to focus on only one or two audience members, as audiences may respond negatively to perceived favouritism. Instead, try to give as much eye contact as possible across the audience. Keep it natural, but give it deliberate thought.

Key Takeaway

To use movement strategically in your presentation, keep it natural and consider using the speaker’s triangle, the three-step sequence, facial gestures, and eye contact.

Exercises

- Think of a message you want to convey to a listener. If you were to dance your message, what would the dance look like? Practice in front of a mirror.

- Ask a friend to record you while you are having a typical conversation with another friend or family member. Watch the video and observe your movements and facial gestures. What would you do differently if you were making a presentation? Discuss your thoughts with a classmate.

- Play “Two Truths and a Lie,” a game in which each person creates three statements (one is a lie) and tells all three statements to a classmate or group. The listeners have to guess which statement is a lie.