This is “International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment”, chapter 2 from the book Challenges and Opportunities in International Business (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 2 International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment

© 2003–2011, Atma Global Inc. Reprinted with permission.

What’s in It for Me?

- What is international trade theory?

- How do political and legal factors impact international trade?

- What is foreign direct investment?

It’s easy to think that trade is just about business interests in each country. But global trade is much more. There’s a convergence and, at times, a conflict of the interests of the different stakeholders—from businesses to governments to local citizens. In recent years, advancements in technology, a renewed enthusiasm for entrepreneurship, and a global sentiment that favors free trade have further connected people, businesses, and markets—all flatteners that are helping expand global trade and investment. An essential part of international business is understanding the history of international trade and what motivates countries to encourage or discourage trade within their borders. In this chapter we’ll look at the evolution of international trade theory to our modern time. We’ll explore the political and legal factors impacting international trade. This chapter will provide an introduction to the concept and role of foreign direct investment, which can take many forms of incentives, regulations, and policies. Companies react to these business incentives and regulations as they evaluate with which countries to do business and in which to invest. Governments often encourage foreign investment in their own country or in another country by providing loans and incentives to businesses in their home country as well as businesses in the recipient country in order to pave the way for investment and trade in the country. The opening case study shows how and why China is investing in the continent of Africa.

Opening Case: China in Africa

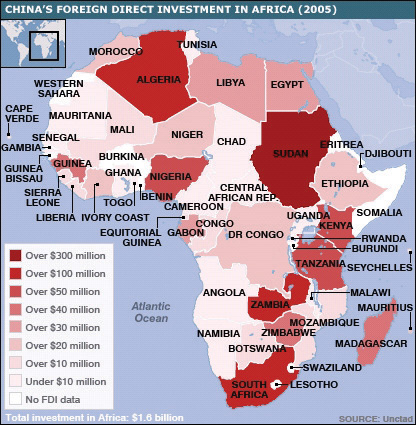

Foreign companies have been doing business in Africa for centuries. Much of the trade history of past centuries has been colored by European colonial powers promoting and preserving their economic interests throughout the African continent.Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa (New York: Public Affairs, 2005). After World War II and since independence for many African nations, the continent has not fared as well as other former colonial countries in Asia. Africa remains a continent plagued by a continued combination of factors, including competing colonial political and economic interests; poor and corrupt local leadership; war, famine, and disease; and a chronic shortage of resources, infrastructure, and political, economic, and social will.“Why Africa Is Poor: Ghana Beats Up on Its Biggest Foreign Investors,” Wall Street Journal, February 18, 2010, accessed February 16, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704804204575069511746613890.html. And yet, through the bleak assessments, progress is emerging, led in large part by the successful emergence of a free and locally powerful South Africa. The continent generates a lot of interest on both the corporate and humanitarian levels, as well as from other countries. In particular in the past decade, Africa has caught the interest of the world’s second largest economy, China.Andrew Rice, “Why Is Africa Still Poor?,” The Nation, October 24, 2005, accessed December 20, 2010, http://www.thenation.com/article/why-africa-still-poor?page=0,1.

At home, over the past few decades, China has undergone its own miracle, managing to move hundreds of millions of its people out of poverty by combining state intervention with economic incentives to attract private investment. Today, China is involved in economic engagement, bringing its success story to the continent of Africa. As professor and author Deborah Brautigam notes, China’s “current experiment in Africa mixes a hard-nosed but clear-eyed self-interest with the lessons of China's own successful development and of decades of its failed aid projects in Africa.”Deborah Brautigam, “Africa’s Eastern Promise: What the West Can Learn from Chinese Investment in Africa,” Foreign Affairs, January 5, 2010, accessed December 20, 2010, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/65916/deborah-brautigam/africa%E2%80%99s-eastern-promise.

According to CNN, “China has increasingly turned to resource-rich Africa as China's booming economy has demanded more and more oil and raw materials.”“China: Trade with Africa on Track to New Record,” CNN, October 15, 2010, accessed April 23, 2011, http://articles.cnn.com/2010-10-15/world/china.africa.trade_1_china-and-africa-link-trade-largest-trade-partner?_s=PM:WORLD. Trade between the African continent and China reached $106.8 billion in 2008, and over the past decade, Chinese investments and the country’s development aid to Africa have been increasing steadily.“China-Africa Trade up 45 percent in 2008 to $107 Billion,” China Daily, February 11, 2009, accessed April 23, 2011, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2009-02/11/content_7467460.htm. “Chinese activities in Africa are highly diverse, ranging from government to government relations and large state owned companies (SOE) investing in Africa financed by China’s policy banks, to private entrepreneurs entering African countries at their own initiative to pursue commercial activities.”Tracy Hon, Johanna Jansson, Garth Shelton, Liu Haifang, Christopher Burke, and Carine Kiala, Evaluating China’s FOCAC Commitments to Africa and Mapping the Way Ahead (Stellenbosch, South Africa: Centre for Chinese Studies, University of Stellenbosch, 2010), 1, accessed December 20, 2010, http://www.ccs.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/ENGLISH-Evaluating-Chinas-FOCAC-commitments-to-Africa-2010.pdf.

Since 2004, eager for access to resources, oil, diamonds, minerals, and commodities, China has entered into arrangements with resource-rich countries in Africa for a total of nearly $14 billion in resource deals alone. In one example with Angola, China provided loans to the country secured by oil. With this investment, Angola hired Chinese companies to build much-needed roads, railways, hospitals, schools, and water systems. Similarly, China provided nearby Nigeria with oil-backed loans to finance projects that use gas to generate electricity. In the Republic of the Congo, Chinese teams are building a hydropower project funded by a Chinese government loan, which will be repaid in oil. In Ghana, a Chinese government loan will be repaid in cocoa beans.Deborah Brautigam, “Africa’s Eastern Promise: What the West Can Learn from Chinese Investment in Africa,” Foreign Affairs, January 5, 2010, accessed December 20, 2010, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/65916/deborah-brautigam/africa%E2%80%99s-eastern-promise.

The Export-Import Bank of China (Ex-Im Bank of China) has funded and has provided these loans at market rates, rather than as foreign aid. While these loans certainly promote development, the risk for the local countries is that the Chinese bids to provide the work aren’t competitive. Furthermore, the benefit to local workers may be diminished as Chinese companies bring in some of their own workers, keeping local wages and working standards low.

In 2007, the UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) Press Office noted the following:

Over the past few years, China has become one of Africa´s important partners for trade and economic cooperation. Trade (exports and imports) between Africa and China increased from US$11 billion in 2000 to US$56 billion in 2006….with Chinese companies present in 48 African countries, although Africa still accounts for only 3 percent of China´s outward FDI [foreign direct investment]. A few African countries have attracted the bulk of China´s FDI in Africa: Sudan is the largest recipient (and the 9th largest recipient of Chinese FDI worldwide), followed by Algeria (18th) and Zambia (19th).United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “Asian Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: United Nations Report Points to a New Era of Cooperation among Developing Countries,” press release, March 27, 2007, accessed December 20, 2010, http://www.unctad.org/Templates/Webflyer.asp?docID=8172&intItemID=3971&lang=1.

Observers note that African governments can learn from the development history of China and many Asian countries, which now enjoy high economic growth and upgraded industrial activity. These Asian countries made strategic investments in education and infrastructure that were crucial not only for promoting economic development in general but also for attracting and benefiting from efficiency-seeking and export-oriented FDI.United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “Foreign Direct Investment in Africa Remains Buoyant, Sustained by Interest in Natural Resources,” press release, September 29, 2005, accessed December 20, 2010, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7086777.stm.

Source: “China in Africa: Developing Ties,” BBC News, last updated November 26, 2007, accessed June 3, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7086777.stm.

Criticized by some and applauded by others, it’s clear that China’s investment is encouraging development in Africa. China is accused by some of ignoring human rights crises in the continent and doing business with repressive regimes. China’s success in Africa is due in large part to the local political environment in each country, where either one or a small handful of leaders often control the power and decision making. While the countries often open bids to many foreign investors, Chinese firms are able to provide low-cost options thanks in large part to their government’s project support. The ability to forge a government-level partnership has enabled Chinese businesses to have long-term investment perspectives in the region. China even hosted a summit in 2006 for African leaders, pledging to increase trade, investment, and aid over the coming decade.“Summit Shows China’s Africa Clout,” BBC News, November 6, 2006, accessed December 20, 2010, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6120500.stm. The 2008 global recession has led China to be more selective in its African investments, looking for good deals as well as political stability in target countries. Nevertheless, whether to access the region’s rich resources or develop local markets for Chinese goods and services, China intends to be a key foreign investor in Africa for the foreseeable future.“China in Africa: Developing Ties,” BBC News, November 26, 2007, accessed December 20, 2010, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7086777.stm.

Opening Case Exercises

(AACSB: Ethical Reasoning, Multiculturalism, Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Describe China’s strategy in Africa.

- If you were the head of a Chinese business that was operating in Sudan, how would you address issues of business ethics and doing business with a repressive regime? Should businesses care about local government ethics and human rights policies?

- If you were a foreign businessperson working for a global oil company that was eager to get favorable government approval to invest in a local oil refinery in an African country, how would you handle any demands for paybacks (i.e., bribes)?

2.1 What Is International Trade Theory?

Learning Objectives

- Understand international trade.

- Compare and contrast different trade theories.

- Determine which international trade theory is most relevant today and how it continues to evolve.

What Is International Trade?

International trade theories are simply different theories to explain international trade. Trade is the concept of exchanging goods and services between two people or entities. International trade is then the concept of this exchange between people or entities in two different countries.

People or entities trade because they believe that they benefit from the exchange. They may need or want the goods or services. While at the surface, this many sound very simple, there is a great deal of theory, policy, and business strategy that constitutes international trade.

In this section, you’ll learn about the different trade theories that have evolved over the past century and which are most relevant today. Additionally, you’ll explore the factors that impact international trade and how businesses and governments use these factors to their respective benefits to promote their interests.

What Are the Different International Trade Theories?

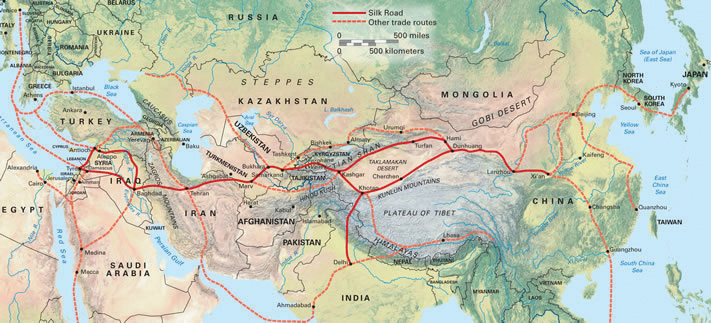

People have engaged in trade for thousands of years. Ancient history provides us with rich examples such as the Silk Road—the land and water trade routes that covered more than four thousand miles and connected the Mediterranean with Asia.

© The Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education

“Around 5,200 years ago, Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, was probably the first city the world had ever seen, housing more than 50,000 people within its six miles of wall. Uruk, its agriculture made prosperous by sophisticated irrigation canals, was home to the first class of middlemen, trade intermediaries…A cooperative trade network…set the pattern that would endure for the next 6,000 years.”Matt Ridley, “Humans: Why They Triumphed,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2010, accessed December 20, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703691804575254533386933138.html.

In more recent centuries, economists have focused on trying to understand and explain these trade patterns. Chapter 1 "Introduction", Section 1.4 "The Globalization Debate" discussed how Thomas Friedman’s flat-world approach segments history into three stages: Globalization 1.0 from 1492 to 1800, 2.0 from 1800 to 2000, and 3.0 from 2000 to the present. In Globalization 1.0, nations dominated global expansion. In Globalization 2.0, multinational companies ascended and pushed global development. Today, technology drives Globalization 3.0.

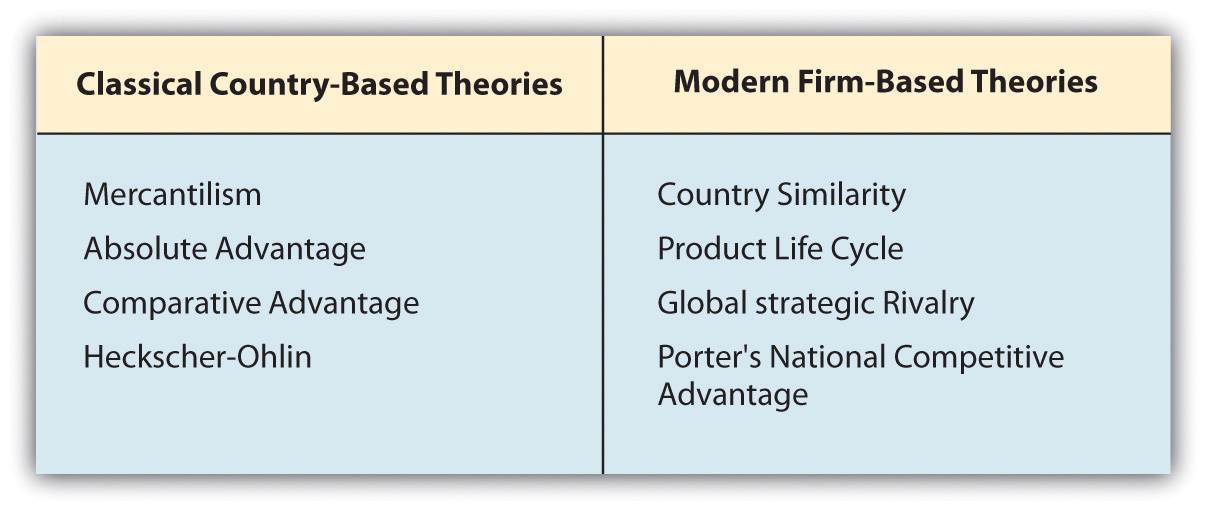

To better understand how modern global trade has evolved, it’s important to understand how countries traded with one another historically. Over time, economists have developed theories to explain the mechanisms of global trade. The main historical theories are called classical and are from the perspective of a country, or country-based. By the mid-twentieth century, the theories began to shift to explain trade from a firm, rather than a country, perspective. These theories are referred to as modern and are firm-based or company-based. Both of these categories, classical and modern, consist of several international theories.

Classical or Country-Based Trade Theories

Mercantilism

Developed in the sixteenth century, mercantilismA classical, country-based international trade theory that states that a country’s wealth is determined by its holdings of gold and silver. was one of the earliest efforts to develop an economic theory. This theory stated that a country’s wealth was determined by the amount of its gold and silver holdings. In it’s simplest sense, mercantilists believed that a country should increase its holdings of gold and silver by promoting exports and discouraging imports. In other words, if people in other countries buy more from you (exports) than they sell to you (imports), then they have to pay you the difference in gold and silver. The objective of each country was to have a trade surplusWhen the value of exports is greater than the value of imports., or a situation where the value of exports are greater than the value of imports, and to avoid a trade deficitWhen the value of imports is greater than the value of exports., or a situation where the value of imports is greater than the value of exports.

A closer look at world history from the 1500s to the late 1800s helps explain why mercantilism flourished. The 1500s marked the rise of new nation-states, whose rulers wanted to strengthen their nations by building larger armies and national institutions. By increasing exports and trade, these rulers were able to amass more gold and wealth for their countries. One way that many of these new nations promoted exports was to impose restrictions on imports. This strategy is called protectionismThe practice of imposing restrictions on imports and protecting domestic industry. and is still used today.

Nations expanded their wealth by using their colonies around the world in an effort to control more trade and amass more riches. The British colonial empire was one of the more successful examples; it sought to increase its wealth by using raw materials from places ranging from what are now the Americas and India. France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain were also successful in building large colonial empires that generated extensive wealth for their governing nations.

Although mercantilism is one of the oldest trade theories, it remains part of modern thinking. Countries such as Japan, China, Singapore, Taiwan, and even Germany still favor exports and discourage imports through a form of neo-mercantilism in which the countries promote a combination of protectionist policies and restrictions and domestic-industry subsidies. Nearly every country, at one point or another, has implemented some form of protectionist policy to guard key industries in its economy. While export-oriented companies usually support protectionist policies that favor their industries or firms, other companies and consumers are hurt by protectionism. Taxpayers pay for government subsidies of select exports in the form of higher taxes. Import restrictions lead to higher prices for consumers, who pay more for foreign-made goods or services. Free-trade advocates highlight how free trade benefits all members of the global community, while mercantilism’s protectionist policies only benefit select industries, at the expense of both consumers and other companies, within and outside of the industry.

Absolute Advantage

In 1776, Adam Smith questioned the leading mercantile theory of the time in The Wealth of Nations.Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776). Recent versions have been edited by scholars and economists. Smith offered a new trade theory called absolute advantageThe ability of a country to produce a good more efficiently than another nation., which focused on the ability of a country to produce a good more efficiently than another nation. Smith reasoned that trade between countries shouldn’t be regulated or restricted by government policy or intervention. He stated that trade should flow naturally according to market forces. In a hypothetical two-country world, if Country A could produce a good cheaper or faster (or both) than Country B, then Country A had the advantage and could focus on specializing on producing that good. Similarly, if Country B was better at producing another good, it could focus on specialization as well. By specialization, countries would generate efficiencies, because their labor force would become more skilled by doing the same tasks. Production would also become more efficient, because there would be an incentive to create faster and better production methods to increase the specialization.

Smith’s theory reasoned that with increased efficiencies, people in both countries would benefit and trade should be encouraged. His theory stated that a nation’s wealth shouldn’t be judged by how much gold and silver it had but rather by the living standards of its people.

Comparative Advantage

The challenge to the absolute advantage theory was that some countries may be better at producing both goods and, therefore, have an advantage in many areas. In contrast, another country may not have any useful absolute advantages. To answer this challenge, David Ricardo, an English economist, introduced the theory of comparative advantage in 1817. Ricardo reasoned that even if Country A had the absolute advantage in the production of both products, specialization and trade could still occur between two countries.

Comparative advantageThe situation in which a country cannot produce a product more efficiently than another country; however, it does produce that product better and more efficiently than it does another good. occurs when a country cannot produce a product more efficiently than the other country; however, it can produce that product better and more efficiently than it does other goods. The difference between these two theories is subtle. Comparative advantage focuses on the relative productivity differences, whereas absolute advantage looks at the absolute productivity.

Let’s look at a simplified hypothetical example to illustrate the subtle difference between these principles. Miranda is a Wall Street lawyer who charges $500 per hour for her legal services. It turns out that Miranda can also type faster than the administrative assistants in her office, who are paid $40 per hour. Even though Miranda clearly has the absolute advantage in both skill sets, should she do both jobs? No. For every hour Miranda decides to type instead of do legal work, she would be giving up $460 in income. Her productivity and income will be highest if she specializes in the higher-paid legal services and hires the most qualified administrative assistant, who can type fast, although a little slower than Miranda. By having both Miranda and her assistant concentrate on their respective tasks, their overall productivity as a team is higher. This is comparative advantage. A person or a country will specialize in doing what they do relatively better. In reality, the world economy is more complex and consists of more than two countries and products. Barriers to trade may exist, and goods must be transported, stored, and distributed. However, this simplistic example demonstrates the basis of the comparative advantage theory.

Heckscher-Ohlin Theory (Factor Proportions Theory)

The theories of Smith and Ricardo didn’t help countries determine which products would give a country an advantage. Both theories assumed that free and open markets would lead countries and producers to determine which goods they could produce more efficiently. In the early 1900s, two Swedish economists, Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin, focused their attention on how a country could gain comparative advantage by producing products that utilized factors that were in abundance in the country. Their theory is based on a country’s production factors—land, labor, and capital, which provide the funds for investment in plants and equipment. They determined that the cost of any factor or resource was a function of supply and demand. Factors that were in great supply relative to demand would be cheaper; factors in great demand relative to supply would be more expensive. Their theory, also called the factor proportions theoryAlso called the Heckscher-Ohlin theory; the classical, country-based international theory states that countries would gain comparative advantage if they produced and exported goods that required resources or factors that they had in great supply and therefore were cheaper production factors. In contrast, countries would import goods that required resources that were in short supply in their country but were in higher demand., stated that countries would produce and export goods that required resources or factors that were in great supply and, therefore, cheaper production factors. In contrast, countries would import goods that required resources that were in short supply, but higher demand.

For example, China and India are home to cheap, large pools of labor. Hence these countries have become the optimal locations for labor-intensive industries like textiles and garments.

Leontief Paradox

In the early 1950s, Russian-born American economist Wassily W. Leontief studied the US economy closely and noted that the United States was abundant in capital and, therefore, should export more capital-intensive goods. However, his research using actual data showed the opposite: the United States was importing more capital-intensive goods. According to the factor proportions theory, the United States should have been importing labor-intensive goods, but instead it was actually exporting them. His analysis became known as the Leontief ParadoxA paradox identified by Russian economist Wassily W. Leontief that states, in the real world, the reverse of the factor proportions theory exists in some countries. For example, even though a country may be abundant in capital, it may still import more capital-intensive goods. because it was the reverse of what was expected by the factor proportions theory. In subsequent years, economists have noted historically at that point in time, labor in the United States was both available in steady supply and more productive than in many other countries; hence it made sense to export labor-intensive goods. Over the decades, many economists have used theories and data to explain and minimize the impact of the paradox. However, what remains clear is that international trade is complex and is impacted by numerous and often-changing factors. Trade cannot be explained neatly by one single theory, and more importantly, our understanding of international trade theories continues to evolve.

Modern or Firm-Based Trade Theories

In contrast to classical, country-based trade theories, the category of modern, firm-based theories emerged after World War II and was developed in large part by business school professors, not economists. The firm-based theories evolved with the growth of the multinational company (MNC). The country-based theories couldn’t adequately address the expansion of either MNCs or intraindustry tradeTrade between two countries of goods produced in the same industry., which refers to trade between two countries of goods produced in the same industry. For example, Japan exports Toyota vehicles to Germany and imports Mercedes-Benz automobiles from Germany.

Unlike the country-based theories, firm-based theories incorporate other product and service factors, including brand and customer loyalty, technology, and quality, into the understanding of trade flows.

Country Similarity Theory

Swedish economist Steffan Linder developed the country similarity theoryA modern, firm-based international trade theory that explains intraindustry trade by stating that countries with the most similarities in factors such as incomes, consumer habits, market preferences, stage of technology, communications, degree of industrialization, and others will be more likely to engage in trade between countries and intraindustry trade will be common. in 1961, as he tried to explain the concept of intraindustry trade. Linder’s theory proposed that consumers in countries that are in the same or similar stage of development would have similar preferences. In this firm-based theory, Linder suggested that companies first produce for domestic consumption. When they explore exporting, the companies often find that markets that look similar to their domestic one, in terms of customer preferences, offer the most potential for success. Linder’s country similarity theory then states that most trade in manufactured goods will be between countries with similar per capita incomes, and intraindustry trade will be common. This theory is often most useful in understanding trade in goods where brand names and product reputations are important factors in the buyers’ decision-making and purchasing processes.

Product Life Cycle Theory

Raymond Vernon, a Harvard Business School professor, developed the product life cycle theoryA modern, firm-based international trade theory that states that a product life cycle has three distinct stages: (1) new product, (2) maturing product, and (3) standardized product. in the 1960s. The theory, originating in the field of marketing, stated that a product life cycle has three distinct stages: (1) new product, (2) maturing product, and (3) standardized product. The theory assumed that production of the new product will occur completely in the home country of its innovation. In the 1960s this was a useful theory to explain the manufacturing success of the United States. US manufacturing was the globally dominant producer in many industries after World War II.

It has also been used to describe how the personal computer (PC) went through its product cycle. The PC was a new product in the 1970s and developed into a mature product during the 1980s and 1990s. Today, the PC is in the standardized product stage, and the majority of manufacturing and production process is done in low-cost countries in Asia and Mexico.

The product life cycle theory has been less able to explain current trade patterns where innovation and manufacturing occur around the world. For example, global companies even conduct research and development in developing markets where highly skilled labor and facilities are usually cheaper. Even though research and development is typically associated with the first or new product stage and therefore completed in the home country, these developing or emerging-market countries, such as India and China, offer both highly skilled labor and new research facilities at a substantial cost advantage for global firms.

Global Strategic Rivalry Theory

Global strategic rivalry theory emerged in the 1980s and was based on the work of economists Paul Krugman and Kelvin Lancaster. Their theory focused on MNCs and their efforts to gain a competitive advantage against other global firms in their industry. Firms will encounter global competition in their industries and in order to prosper, they must develop competitive advantages. The critical ways that firms can obtain a sustainable competitive advantage are called the barriers to entry for that industry. The barriers to entryThe obstacles a new firm may face when trying to enter into an industry or new market. refer to the obstacles a new firm may face when trying to enter into an industry or new market. The barriers to entry that corporations may seek to optimize include:

- research and development,

- the ownership of intellectual property rights,

- economies of scale,

- unique business processes or methods as well as extensive experience in the industry, and

- the control of resources or favorable access to raw materials.

Porter’s National Competitive Advantage Theory

In the continuing evolution of international trade theories, Michael Porter of Harvard Business School developed a new model to explain national competitive advantage in 1990. Porter’s theoryA modern, firm-based international trade theory that states that a nation’s or firm’s competitiveness in an industry depends on the capacity of the industry and firm to innovate and upgrade. In addition to the roles of government and chance, this theory identifies four key determinants of national competitiveneness: (1) local market resources and capabilities, (2) local market demand conditions, (3) local suppliers and complementary industries, and (4) local firm characteristics. stated that a nation’s competitiveness in an industry depends on the capacity of the industry to innovate and upgrade. His theory focused on explaining why some nations are more competitive in certain industries. To explain his theory, Porter identified four determinants that he linked together. The four determinants are (1) local market resources and capabilities, (2) local market demand conditions, (3) local suppliers and complementary industries, and (4) local firm characteristics.

- Local market resources and capabilities (factor conditions). Porter recognized the value of the factor proportions theory, which considers a nation’s resources (e.g., natural resources and available labor) as key factors in determining what products a country will import or export. Porter added to these basic factors a new list of advanced factors, which he defined as skilled labor, investments in education, technology, and infrastructure. He perceived these advanced factors as providing a country with a sustainable competitive advantage.

- Local market demand conditions. Porter believed that a sophisticated home market is critical to ensuring ongoing innovation, thereby creating a sustainable competitive advantage. Companies whose domestic markets are sophisticated, trendsetting, and demanding forces continuous innovation and the development of new products and technologies. Many sources credit the demanding US consumer with forcing US software companies to continuously innovate, thus creating a sustainable competitive advantage in software products and services.

- Local suppliers and complementary industries. To remain competitive, large global firms benefit from having strong, efficient supporting and related industries to provide the inputs required by the industry. Certain industries cluster geographically, which provides efficiencies and productivity.

- Local firm characteristics. Local firm characteristics include firm strategy, industry structure, and industry rivalry. Local strategy affects a firm’s competitiveness. A healthy level of rivalry between local firms will spur innovation and competitiveness.

In addition to the four determinants of the diamond, Porter also noted that government and chance play a part in the national competitiveness of industries. Governments can, by their actions and policies, increase the competitiveness of firms and occasionally entire industries.

Porter’s theory, along with the other modern, firm-based theories, offers an interesting interpretation of international trade trends. Nevertheless, they remain relatively new and minimally tested theories.

Which Trade Theory Is Dominant Today?

The theories covered in this chapter are simply that—theories. While they have helped economists, governments, and businesses better understand international trade and how to promote, regulate, and manage it, these theories are occasionally contradicted by real-world events. Countries don’t have absolute advantages in many areas of production or services and, in fact, the factors of production aren’t neatly distributed between countries. Some countries have a disproportionate benefit of some factors. The United States has ample arable land that can be used for a wide range of agricultural products. It also has extensive access to capital. While it’s labor pool may not be the cheapest, it is among the best educated in the world. These advantages in the factors of production have helped the United States become the largest and richest economy in the world. Nevertheless, the United States also imports a vast amount of goods and services, as US consumers use their wealth to purchase what they need and want—much of which is now manufactured in other countries that have sought to create their own comparative advantages through cheap labor, land, or production costs.

As a result, it’s not clear that any one theory is dominant around the world. This section has sought to highlight the basics of international trade theory to enable you to understand the realities that face global businesses. In practice, governments and companies use a combination of these theories to both interpret trends and develop strategy. Just as these theories have evolved over the past five hundred years, they will continue to change and adapt as new factors impact international trade.

Key Takeaways

- Trade is the concept of exchanging goods and services between two people or entities. International trade is the concept of this exchange between people or entities in two different countries. While a simplistic definition, the factors that impact trade are complex, and economists throughout the centuries have attempted to interpret trends and factors through the evolution of trade theories.

- There are two main categories of international trade—classical, country-based and modern, firm-based.

- Porter’s theory states that a nation’s competitiveness in an industry depends on the capacity of the industry to innovate and upgrade. He identified four key determinants: (1) local market resources and capabilities (factor conditions), (2) local market demand conditions, (3) local suppliers and complementary industries, and (4) local firm characteristics.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- What is international trade?

- Summarize the classical, country-based international trade theories. What are the differences between these theories, and how did the theories evolve?

- What are the modern, firm-based international trade theories?

- Describe how a business may use the trade theories to develop its business strategies. Use Porter’s four determinants in your explanation.

2.2 Political and Legal Factors That Impact International Trade

Learning Objectives

- Know the different political systems.

- Identify the different legal systems.

- Understand government-business trade relations and how political and legal factors impact international business.

Why should businesses care about the different political and legal systems around the world? To begin with, despite the globalization of business, firms must abide by the local rules and regulations of the countries in which they operate. In the case study in Chapter 1 "Introduction", you discovered how US-based Google had to deal with the Chinese government’s restrictions on the freedom of speech in order to do business in China. China’s different set of political and legal guidelines made Google choose to discontinue its mainland Chinese version of its site and direct mainland Chinese users to a Hong Kong version.

Until recently, governments were able to directly enforce the rules and regulations based on their political and legal philosophies. The Internet has started to change this, as sellers and buyers have easier access to each other. Nevertheless, countries still have the ability to regulate or strong-arm companies into abiding by their rules and regulations. As a result, global businesses monitor and evaluate the political and legal climate in countries in which they currently operate or hope to operate in the future.

Before we can evaluate the impact on business, let’s first look at the different political and legal systems.

What Are the Different Political Systems?

The study of political systems is extensive and complex. A political systemThe system of politics and government in a country; it governs a complete set of rules, regulations, institutions, and attitudes. is basically the system of politics and government in a country. It governs a complete set of rules, regulations, institutions, and attitudes. A main differentiator of political systems is each system’s philosophy on the rights of the individual and the group as well as the role of government. Each political system’s philosophy impacts the policies that govern the local economy and business environment.

There are more than thirteen major types of government, each of which consists of multiple variations. Let’s focus on the overarching modern political philosophies. At one end of the extremes of political philosophies, or ideologies, is anarchismA political ideology that contends that individuals should control political activities and public government is both unnecessary and unwanted., which contends that individuals should control political activities and public government is both unnecessary and unwanted. At the other extreme is totalitarianismA political ideology that contends that every aspect of an individual’s life should be controlled and dictated by a strong central government., which contends that every aspect of an individual’s life should be controlled and dictated by a strong central government. In reality, neither extreme exists in its purest form. Instead, most countries have a combination of both, the balance of which is often a reflection of the country’s history, culture, and religion. This combination is called pluralismA political ideology that asserts that both public and private groups are important in a well-functioning political system., which asserts that both public and private groups are important in a well-functioning political system. Although most countries are pluralistic politically, they may lean more to one extreme than the other.

In some countries, the government controls more aspects of daily life than in others. While the common usage treats totalitarian and authoritarian as synonyms, there is a distinct difference. For the purpose of this discussion, the main relevant difference is in ideology. Authoritarian governments centralize all control in the hands of one strong leader or a small group of leaders, who have full authority. These leaders are not democratically elected and are not politically, economically, or socially accountable to the people in the country. Totalitarianism, a more extreme form of authoritarianism, occurs when an authoritarian leadership is motivated by a distinct ideology, such as communism. In totalitarianism, the ideology influences or controls the people, not just a person or party. Authoritarian leaders tend not to have a guiding philosophy and use more fear and corruption to maintain control.

DemocracyA form of government that derives its power from the people. is the most common form of government around the world today. Democratic governments derive their power from the people of the country, either by direct referendum (called a direct democracy) or by means of elected representatives of the people (a representative democracy). Democracy has a number of variations, both in theory and practice, some of which provide better representation and more freedoms for their citizens than others.

Did You Know?

It may seem evident that businesses would prefer to operate in open, democratic countries; however, it can be difficult to determine which countries fit the democratic criteria. As a result, there are a variety of institutions, including the Economist, which analyze and rate countries based on their openness and adherence to democratic principles.

There is no consensus on how to measure democracy, definitions of democracy are contested and there is an ongoing lively debate on the subject. Although the terms “freedom” and “democracy” are often used interchangeably, the two are not synonymous. Democracy can be seen as a set of practices and principles that institutionalise and thus ultimately protect freedom. Even if a consensus on precise definitions has proved elusive, most observers today would agree that, at a minimum, the fundamental features of a democracy include government based on majority rule and the consent of the governed, the existence of free and fair elections, the protection of minorities and respect for basic human rights. Democracy presupposes equality before the law, due process and political pluralism.“Liberty and Justice for Some,” Economist, August 22, 2007, accessed December 21, 2010, http://www.economist.com/node/8908438.

To further illustrate the complexity of the definition of a democracy, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual “Index of Democracy” uses a detailed questionnaire and analysis process to provide “a snapshot of the current state of democracy worldwide for 165 independent states and two territories (this covers almost the entire population of the world and the vast majority of the world’s independent states (27 micro states are excluded) [as of 2008)].”Economist Intelligence Unit, “The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy 2008,” Economist, October 29, 2008, accessed December 21, 2010, http://graphics.eiu.com/PDF/Democracy%20Index%202008.pdf. Several things stand out in the 2008 index.

Although almost half of the world’s countries can be considered to be democracies, the number of “full democracies” is relatively low (only 30); 50 are rated as “flawed democracies.” Of the remaining 87 states, 51 are authoritarian and 36 are considered to be “hybrid regimes.” As could be expected, the developed OECD countries dominate among full democracies, although there are two Latin American, two central European and one African country, which suggest that the level of development is not a binding constraint. Only two Asian countries are represented: Japan and South Korea.

Half of the world’s population lives in a democracy of some sort, although only some 14 percent reside in full democracies. Despite the advances in democracy in recent decades, more than one third the world’s population still lives under authoritarian rule. Economist Intelligence Unit, “The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy 2008,” Economist, October 29, 2008, accessed December 21, 2010, http://graphics.eiu.com/PDF/Democracy%20Index%202008.pdf.

What businesses must focus on is how a country’s political system impacts the economy as well as the particular firm and industry. Firms need to assess the balance to determine how local policies, rules, and regulations will affect their business. Depending on how long a company expects to operate in a country and how easy it is for it to enter and exit, a firm may also assess the country’s political risk and stability. A company may ask several questions regarding a prospective country’s government to assess possible risks:

- How stable is the government?

- Is it a democracy or a dictatorship?

- If a new party comes into power, will the rules of business change dramatically?

- Is power concentrated in the hands of a few, or is it clearly outlined in a constitution or similar national legal document?

- How involved is the government in the private sector?

- Is there a well-established legal environment both to enforce policies and rules as well as to challenge them?

- How transparent is the government’s political, legal, and economic decision-making process?

While any country can, in theory, pose a risk in all of these factors, some countries offer a more stable business environment than others. In fact, political stability is a key part of government efforts to attract foreign investment to their country. Businesses need to assess if a country believes in free markets, government control, or heavy intervention (often to the benefit of a few) in industry. The country’s view on capitalism is also a factor for business consideration. In the broadest sense, capitalismAn economic system in which the means of production are owned and controlled privately. is an economic system in which the means of production are owned and controlled privately. In contrast, a planned economyAn economic system in which the government or state directs and controls the economy, including the means and decision making for production. is one in which the government or state directs and controls the economy, including the means and decision making for production. Historically, democratic governments have supported capitalism and authoritarian regimes have tended to utilize a state-controlled approach to managing the economy.

As you might expect, established democracies, such as those found in the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, and Australia, offer a high level of political stability. While many countries in Asia and Latin America also are functioning democracies, their stage of development impacts the stability of their economic and trade policy, which can fluctuate with government changes. Chapter 4 "World Economies" provides more details about developed and developing countries and emerging markets.

Within reason, in democracies, businesses understand that most rules survive changes in government. Any changes are usually a reflection of a changing economic environment, like the world economic crisis of 2008, and not a change in the government players.

This contrasts with more authoritarian governments, where democracy is either not in effect or simply a token process. China is one of the more visible examples, with its strong government and limited individual rights. However, in the past two decades, China has pursued a new balance of how much the state plans and manages the national economy. While the government still remains the dominant force by controlling more than a third of the economy, more private businesses have emerged. China has successfully combined state intervention with private investment to develop a robust, market-driven economy—all within a communist form of government. This system is commonly referred to as “a socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics.” The Chinese are eager to portray their version of combining an authoritarian form of government with a market-oriented economy as a better alternative model for fledging economies, such as those in Africa. This new combination has also posed more questions for businesses that are encountering new issues—such as privacy, individual rights, and intellectual rights protections—as they try to do business with China, now the second-largest economy in the world behind the United States. The Chinese model of an authoritarian government and a market-oriented economy has, at times, tilted favor toward companies, usually Chinese, who understand how to navigate the nuances of this new system. Chinese government control on the Internet, for example, has helped propel homegrown, Baidu, a Chinese search engine, which earns more than 73 percent of the Chinese search-engine revenues. Baidu self-censors and, as a result, has seen its revenues soar after Google limited its operations in the country.Rolfe Winkler, “Internet Plus China Equals Screaming Baidu,” Wall Street Journal, November 9, 2010, accessed December 21, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703514904575602781130437538.html.

It might seem straightforward to assume that businesses prefer to operate only in democratic, capitalist countries where there is little or no government involvement or intervention. However, history demonstrates that, for some industries, global firms have chosen to do business with countries whose governments control that industry. Businesses in industries, such as commodities and oil, have found more authoritarian governments to be predictable partners for long-term access and investment for these commodities. The complexity of trade in these situations increases, as throughout history, governments have come to the aid and protection of their nation’s largest business interests in markets around the world. The history of the oil industry shows how various governments have, on occasion, protected their national companies’ access to oil through political force. In current times, the Chinese government has been using a combination of government loans and investment in Africa to obtain access for Chinese companies to utilize local resources and commodities. Many business analysts mention these issues in discussions of global business ethics and the role and responsibility of companies in different political environments.

What Are the Different Legal Systems?

Let’s focus briefly on how the political and economic ideologies that define countries impact their legal systems. In essence, there are three main kinds of legal systems—common law, civil law, and religious or theocratic law. Most countries actually have a combination of these systems, creating hybrid legal systems.

Civil lawA legal system based on a detailed set of laws that constitute a code and on how the law is applied to the facts. is based on a detailed set of laws that constitute a code and focus on how the law is applied to the facts. It’s the most widespread legal system in the world.

Common lawA legal system based on traditions and precedence. In this system, judges interpret the law and judicial rulings can set precedent. is based on traditions and precedence. In common law systems, judges interpret the law and judicial rulings can set precedent.

Religious lawAlso known as theocratic law; this legal system is based on religious guidelines. is also known as theocratic law and is based on religious guidelines. The most commonly known example of religious law is Islamic law, also known as ShariaIslamic religious law that addresses all aspect of daily life; in terms of business and finance, the law prohibits charging interest on money and other common investment activities, including hedging and short selling.. Islamic law governs a number of Islamic nations and communities around the world and is the most widely accepted religious law system. Two additional religious law systems are the Jewish Halacha and the Christian Canon system, neither of which is practiced at the national level in a country. The Christian Canon system is observed in the Vatican City.

The most direct impact on business can be observed in Islamic law—which is a moral, rather than a commercial, legal system. Sharia has clear guidelines for aspects of life. For example, in Islamic law, business is directly impacted by the concept of interest. According to Islamic law, banks cannot charge or benefit from interest. This provision has generated an entire set of financial products and strategies to simulate interest—or a gain—for an Islamic bank, while not technically being classified as interest. Some banks will charge a large up-front fee. Many are permitted to engage in sale-buyback or leaseback of an asset. For example, if a company wants to borrow money from an Islamic bank, it would sell its assets or product to the bank for a fixed price. At the same time, an agreement would be signed for the bank to sell back the assets to the company at a later date and at a higher price. The difference between the sale and buyback price functions as the interest. In the Persian Gulf region alone, there are twenty-two Sharia-compliant, Islamic banks, which in 2008 had approximately $300 billion in assets.Tala Malik, “Gulf Islamic Bank Assets to Hit $300bn,” Arabian Business, February 20, 2008, accessed December 21, 2010, http://www.arabianbusiness.com/511804-gulf-islamic-banks-assets-to-hit-300bn. Clearly, many global businesses and investment banks are finding creative ways to do business with these Islamic banks so that they can comply with Islamic law while earning a profit.

Government—Business Trade Relations: The Impact of Political and Legal Factors on International Trade

How do political and legal realities impact international trade, and what do businesses need to think about as they develop their global strategy? Governments have long intervened in international trade through a variety of mechanisms. First, let’s briefly discuss some of the reasons behind these interventions.

Why Do Governments Intervene in Trade?

Governments intervene in trade for a combination of political, economic, social, and cultural reasons.

Politically, a country’s government may seek to protect jobs or specific industries. Some industries may be considered essential for national security purposes, such as defense, telecommunications, and infrastructure—for example, a government may be concerned about who owns the ports within its country. National security issues can impact both the import and exports of a country, as some governments may not want advanced technological information to be sold to unfriendly foreign interests. Some governments use trade as a retaliatory measure if another country is politically or economically unfair. On the other hand, governments may influence trade to reward a country for political support on global matters.

Did You Know?

State Capitalism: Governments Seeking to Control Key Industries

Despite the movement toward privatizing industry and free trade, government interests in their most valuable commodity, oil, remains constant. The thirteen largest oil companies (as measured by the reserves they control) in the world are all state-run and all are bigger than ExxonMobil, which is the world’s largest private oil company. State-owned companies control more than 75 percent of all crude oil production, in contrast with only 10 percent for private multinational oil firms.Ian Bremmer, “The Long Shadow of the Visible Hand,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2010, accessed December 21, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704852004575258541875590852.html; “Really Big Oil,” Economist, August 10, 2006, accessed December 21, 2010, http://www.economist.com/node/7276986.

Table 2.1 The Major Global State-Owned Oil Companies

| Aramco | Saudi Arabia |

| Gazprom | Russia |

| China National Petroleum Corp. | China |

| National Iranian Oil Co. | Iran |

| Petróleos de Venezuela | Venezuela |

| Petrobras | Brazil |

| Petronas | Malaysia |

Source: Energy Intelligence Group, “Petroleum Intelligence Weekly Ranks World’s Top 50 Oil Companies (2009),” news release, December 1, 2008, accessed December 21, 2010, http://www.energyintel.com/documentdetail.asp?document_id=245527.

In the past thirty years, governments have increasingly privatized a number of industries. However, “in defense, power generation, telecoms, metals, minerals, aviation, and other sectors, a growing number of emerging-market governments, not content with simply regulating markets, are moving to dominate them.”Ian Bremmer, “The Long Shadow of the Visible Hand,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2010, accessed December 21, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704852004575258541875590852.html.

State companies, like their private sector counterparts, get to keep the profits from oil production, creating a significant incentive for governments to either maintain or regain control of this very lucrative industry. Whether the motive is economic (i.e., profit) or political (i.e., state control), “foreign firms and investors find that national and local rules and regulations are increasingly designed to favor domestic firms at their expense. Multinationals now find themselves competing as never before with state-owned companies armed with substantial financial and political support from their governments.”Ian Bremmer, “The Long Shadow of the Visible Hand,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2010, accessed December 21, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704852004575258541875590852.html.

Governments are also motivated by economic factors to intervene in trade. They may want to protect young industries or to preserve access to local consumer markets for domestic firms.

Cultural and social factors might also impact a government’s intervention in trade. For example, some countries’ governments have tried to limit the influence of American culture on local markets by limiting or denying the entry of American companies operating in the media, food, and music industries.

How Do Governments Intervene in Trade?

While the past century has seen a major shift toward free trade, many governments continue to intervene in trade. Governments have several key policy areas that can be used to create rules and regulations to control and manage trade.

- Tariffs. Tariffs are taxes imposed on imports. Two kinds of tariffs exist—specific tariffsTaxes or tariffs that are levied as a fixed charge, regardless of the value of the product or service., which are levied as a fixed charge, and ad valorem tariffsTariffs that are calculated as a percentage of the value of the product or service., which are calculated as a percentage of the value. Many governments still charge ad valorem tariffs as a way to regulate imports and raise revenues for their coffers.

- Subsidies. A subsidy is a form of government payment to a producer. Types of subsidies include tax breaks or low-interest loans; both of which are common. Subsidies can also be cash grants and government-equity participation, which are less common because they require a direct use of government resources.

- Import quotas and VER. Import quotas and voluntary export restraints (VER) are two strategies to limit the amount of imports into a country. The importing government directs import quotas, while VER are imposed at the discretion of the exporting nation in conjunction with the importing one.

- Currency controls. Governments may limit the convertibility of one currency (usually its own) into others, usually in an effort to limit imports. Additionally, some governments will manage the exchange rate at a high level to create an import disincentive.

- Local content requirements. Many countries continue to require that a certain percentage of a product or an item be manufactured or “assembled” locally. Some countries specify that a local firm must be used as the domestic partner to conduct business.

- Antidumping rules. Dumping occurs when a company sells product below market price often in order to win market share and weaken a competitor.

- Export financing. Governments provide financing to domestic companies to promote exports.

- Free-trade zone. Many countries designate certain geographic areas as free-trade zones. These areas enjoy reduced tariffs, taxes, customs, procedures, or restrictions in an effort to promote trade with other countries.

- Administrative policies. These are the bureaucratic policies and procedures governments may use to deter imports by making entry or operations more difficult and time consuming.

Did You Know?

Government Intervention in China

As shown in the opening case study, China is using its economic might to invest in Africa. China’s ability to focus on dominating key industries inspires both fear and awe throughout the world. A closer look at the solar industry in China illustrates the government’s ability to create new industries and companies based on its objectives. With its huge population, China is in constant need of energy to meet the needs of its people and businesses.

Fast-growing China has an insatiable appetite for energy.

© 2011, Atma Global Inc. All rights reserved.

As a result, the government has placed a priority on energy related technologies, including solar energy. China’s expanding solar-energy industry is dependent on polycrystalline silicon, the main raw material for solar panels. Facing a shortage in 2007, growing domestic demand, and high prices from foreign companies that dominated production, China declared the development of domestic polysilicon supplies a priority. Domestic Chinese manufacturers received quick loans with favorable terms as well as speedy approvals. One entrepreneur, Zhu Gongshan, received $1 billion in funding, including a sizeable investment from China’s sovereign wealth fund, in record time, enabling his firm GCL-Poly Energy Holding to become one of the world’s biggest in less than three years. The company now has a 25 percent market share of polysilicon and almost 50 percent of the global market for solar-power equipment.Jason Dean, Andrew Browne, and Shai Oster, “China’s ‘State Capitalism’ Sparks Global Backlash,” Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2010, accessed December 22, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703514904575602731006315198.html.

How did this happen so fast? Many observers note that it was the direct result of Chinese government intervention in what was deemed a key industry.

Central to China’s approach are policies that champion state-owned firms and other so-called national champions, seek aggressively to obtain advanced technology, and manage its exchange rate to benefit exporters. It leverages state control of the financial system to channel low-cost capital to domestic industries—and to resource-rich foreign nations (such as those we read in the opening case) whose oil and minerals China needs to maintain rapid growth.Jason Dean, Andrew Browne, and Shai Oster, “China’s ‘State Capitalism’ Sparks Global Backlash,” Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2010, accessed December 22, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703514904575602731006315198.html.

Understanding the balance between China’s government structure and its ideology is essential to doing business in this complex country. China is both an emerging market and a rising superpower. Its leaders see the economy as a tool to preserving the state’s power, which in turn is essential to maintaining stability and growth and ensuring the long-term viability of the Communist Party.Jason Dean, Andrew Browne, and Shai Oster, “China’s ‘State Capitalism’ Sparks Global Backlash,” Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2010, accessed December 22, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703514904575602731006315198.html.

Contrary to the approach of much of the world, which is moving more control to the private sector, China has steadfastly maintained its state control. For example, the Chinese government owns almost all the major banks, the three largest oil companies, the three telecommunications carriers, and almost all of the media.

China’s Communist Party outlines its goals in five-year plans. The most recent one emphasizes the government’s goal for China to become a technology powerhouse by 2020 and highlights key areas such as green technology, hence the solar industry expansion. Free trade advocates perceive this government-directed intervention as an unfair tilt against the global private sector. Nevertheless, global companies continue to seek the Chinese market, which offers much-needed growth and opportunity.Jason Dean, Andrew Browne, and Shai Oster, “China’s ‘State Capitalism’ Sparks Global Backlash,” Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2010, accessed December 22, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703514904575602731006315198.html.

Key Takeaways

- There are more than thirteen major types of government and each type consists of multiple variations. At one end of the political ideology extremes is anarchism, which contends that individuals should control political activities and public government is both unnecessary and unwanted. The other extreme is totalitarianism, which contends that every aspect of an individual’s life should be controlled and dictated by a strong central government. Neither extreme exists in its purest form in the real world. Instead, most countries have a combination of both. This combination is called pluralism, which asserts that both public and private groups are important in a well-functioning political system. Democracy is the most common form of government today. Democratic governments derive their power from the people of the country either by direct referendum, called a direct democracy, or by means of elected representatives of the people, known as a representative democracy.

- Capitalism is an economic system in which the means of production are owned and controlled privately. In contrast a planned economy is one in which the government or state directs and controls the economy.

- There are three main types of legal systems: (1) civil law, (2) common law, and (3) religious law. In practice, countries use a combination of one or more of these systems and often adapt them to suit the local values and culture.

- Government-business trade relations are the relationships between national governments and global businesses. Governments intervene in trade to protect their nation’s economy and industry, as well as promote and preserve their social, cultural, political, and economic structures and philosophies. Governments have several key policy areas in which they can create rules and regulations in order to control and manage trade, including tariffs, subsidies; import quotas and VER, currency controls, local content requirements, antidumping rules, export financing, free-trade zones, and administrative policies.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Identify the main political ideologies.

- What is capitalism? What is a planned economy? Compare and contrast the two forms of economic ideology discussed in this section.

- What are three policy areas in which governments can create rules and regulations in order to control, manage, and intervene in trade.

2.3 Foreign Direct Investment

Learning Objectives

- Understand the types of international investments.

- Identify the factors that influence foreign direct investment (FDI).

- Explain why and how governments encourage FDI in their countries.

Understand the Types of International Investments

There are two main categories of international investment—portfolio investment and foreign direct investment. Portfolio investmentThe investment in a company’s stocks, bonds, or assets, but not for the purpose of controlling or directing the firm’s operations or management. refers to the investment in a company’s stocks, bonds, or assets, but not for the purpose of controlling or directing the firm’s operations or management. Typically, investors in this category are looking for a financial rate of return as well as diversifying investment risk through multiple markets.

Foreign direct investment (FDI)The acquisition of foreign assets with the intent to control and manage them. refers to an investment in or the acquisition of foreign assets with the intent to control and manage them. Companies can make an FDI in several ways, including purchasing the assets of a foreign company; investing in the company or in new property, plants, or equipment; or participating in a joint venture with a foreign company, which typically involves an investment of capital or know-how. FDI is primarily a long-term strategy. Companies usually expect to benefit through access to local markets and resources, often in exchange for expertise, technical know-how, and capital. A country’s FDI can be both inward and outward. As the terms would suggest, inward FDIAn investment into a country by a company from another country. refers to investments coming into the country and outward FDIAn investment made by a domestic company into companies in other countries. are investments made by companies from that country into foreign companies in other countries. The difference between inward and outward is called the net FDI inflow, which can be either positive or negative.

Governments want to be able to control and regulate the flow of FDI so that local political and economic concerns are addressed. Global businesses are most interested in using FDI to benefit their companies. As a result, these two players—governments and companies—can at times be at odds. It’s important to understand why companies use FDI as a business strategy and how governments regulate and manage FDI.

Factors That Influence a Company’s Decision to Invest

Let’s look at why and how companies choose to invest in foreign markets. Simply purchasing goods and services or deciding to invest in a local market depends on a business’s needs and overall strategy. Direct investment in a country occurs when a company chooses to set up facilities to produce or market their products; or seeks to partner with, invest in, or purchase a local company for control and access to the local market, production, or resources. Many considerations influence its decisions:

- Cost. Is it cheaper to produce in the local market than elsewhere?

- Logistics. Is it cheaper to produce locally if the transportation costs are significant?

- Market. Has the company identified a significant local market?

- Natural resources. Is the company interested in obtaining access to local resources or commodities?

- Know-how. Does the company want access to local technology or business process knowledge?

- Customers and competitors. Does the company’s clients or competitors operate in the country?

- Policy. Are there local incentives (cash and noncash) for investing in one country versus another?

- Ease. Is it relatively straightforward to invest and/or set up operations in the country, or is there another country in which setup might be easier?

- Culture. Is the workforce or labor pool already skilled for the company’s needs or will extensive training be required?

- Impact. How will this investment impact the company’s revenue and profitability?

- Expatriation of funds. Can the company easily take profits out of the country, or are there local restrictions?

- Exit. Can the company easily and orderly exit from a local investment, or are local laws and regulations cumbersome and expensive?

These are just a few of the many factors that might influence a company’s decision. Keep in mind that a company doesn’t need to sell in the local market in order to deem it a good option for direct investment. For example, companies set up manufacturing facilities in low-cost countries but export the products to other markets.

There are two forms of FDI—horizontal and vertical. Horizontal FDIWhen a company is trying to open up a new market that is similar to its domestic markets. occurs when a company is trying to open up a new market—a retailer, for example, that builds a store in a new country to sell to the local market. Vertical FDIWhen a company invests internationally to provide input into its core operations usually in its home country. A firm may invest in production facilities in another country. If the firm brings the goods or components back to its home country (acting as a supplier), then it is called backward vertical FDI. If the firm sells the goods into the local or regional market (acting more as a distributor), then it is referred to as forward vertical FDI. is when a company invests internationally to provide input into its core operations—usually in its home country. A firm may invest in production facilities in another country. When a firm brings the goods or components back to its home country (i.e., acting as a supplier), this is referred to as backward vertical FDI. When a firm sells the goods into the local or regional market (i.e., acting as a distributor), this is termed forward vertical FDI. The largest global companies often engage in both backward and forward vertical FDI depending on their industry.

Many firms engage in backward vertical FDI. The auto, oil, and infrastructure (which includes industries related to enhancing the infrastructure of a country—that is, energy, communications, and transportation) industries are good examples of this. Firms from these industries invest in production or plant facilities in a country in order to supply raw materials, parts, or finished products to their home country. In recent years, these same industries have also started to provide forward FDI by supplying raw materials, parts, or finished products to newly emerging local or regional markets.

There are different kinds of FDI, two of which—greenfield and brownfield—are increasingly applicable to global firms. Greenfield FDIsAn FDI strategy in which a company builds new facilities from scratch. occur when multinational corporations enter into developing countries to build new factories or stores. These new facilities are built from scratch—usually in an area where no previous facilities existed. The name originates from the idea of building a facility on a green field, such as farmland or a forested area. In addition to building new facilities that best meet their needs, the firms also create new long-term jobs in the foreign country by hiring new employees. Countries often offer prospective companies tax breaks, subsidies, and other incentives to set up greenfield investments.

A brownfield FDIAn FDI strategy in which a company or government entity purchases or leases existing production facilities to launch a new production activity. is when a company or government entity purchases or leases existing production facilities to launch a new production activity. One application of this strategy is where a commercial site used for an “unclean” business purpose, such as a steel mill or oil refinery, is cleaned up and used for a less polluting purpose, such as commercial office space or a residential area. Brownfield investment is usually less expensive and can be implemented faster; however, a company may have to deal with many challenges, including existing employees, outdated equipment, entrenched processes, and cultural differences.

You should note that the terms greenfield and brownfield are not exclusive to FDI; you may hear them in various business contexts. In general, greenfield refers to starting from the beginning, and brownfield refers to modifying or upgrading existing plans or projects.

Why and How Governments Encourage FDI

Many governments encourage FDI in their countries as a way to create jobs, expand local technical knowledge, and increase their overall economic standards.Ian Bremmer, The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations (New York: Portfolio, 2010). Countries like Hong Kong and Singapore long ago realized that both global trade and FDI would help them grow exponentially and improve the standard of living for their citizens. As a result, Hong Kong (before its return to China) was one of the easiest places to set up a new company. Guidelines were clearly available, and businesses could set up a new office within days. Similarly, Singapore, while a bit more discriminatory on the size and type of business, offered foreign companies a clear, streamlined process for setting up a new company.

In contrast, for decades, many other countries in Asia (e.g., India, China, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Indonesia) restricted or controlled FDI in their countries by requiring extensive paperwork and bureaucratic approvals as well as local partners for any new foreign business. These policies created disincentives for many global companies. By the 1990s (and earlier for China), many of the countries in Asia had caught the global trade bug and were actively trying to modify their policies to encourage more FDI. Some were more successful than others, often as a result of internal political issues and pressures rather than from any repercussions of global trade.UNCTAD compiles statistics on foreign direct investment (FDI): “Foreign Direct Investment database,” UNCTAD United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, accessed February 16, 2011, http://unctadstat.unctad.org/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?sRF_ActivePath=P,5,27&sRF_Expanded=,P,5,27&sCS_ChosenLang=en.

How Governments Discourage or Restrict FDI

In most instances, governments seek to limit or control foreign direct investment to protect local industries and key resources (oil, minerals, etc.), preserve the national and local culture, protect segments of their domestic population, maintain political and economic independence, and manage or control economic growth. A government use various policies and rules: