This is “Case Studies”, section 3.5 from the book Business Ethics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.5 Case Studies

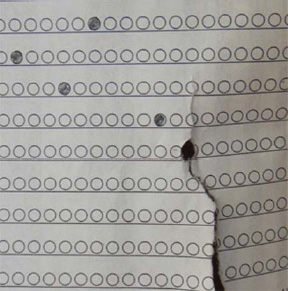

Cheaters

Source: Photo courtesy of S. Brusseau.

KDCP is Karen Dillard’s company specialized in preparing students to ace the Scholastic Aptitude Test. At least some of the paying students received a solid testing-day advantage: besides teaching the typical tips and pointers, KDCP acquired stolen SAT tests and used them in their training sessions. It’s unclear how many of the questions that students practiced on subsequently turned up on the SATs they took, but some certainly did. The company that produces the SAT, the College Board, cried foul and took KDCP to court. The lawsuit fell into the category of copyright infringement, but the real meat of the claim was that KDCP helped kids cheat, they got caught, and now they should pay.

The College Board’s case was very strong. After KDCP accepted the cold reality that they were going to get hammered, they agreed to a settlement offer from the College Board that included this provision: KDCP would provide $400,000 worth of free SAT prep classes to high schoolers who couldn’t afford to pay the bill themselves.missypie, April 29, 2008 (2:22 p.m.), “CB-Karen Dillard case settled-no cancelled scores,” College Confidential, accessed May 15, 2011, http://talk.collegeconfidential.com/parents-forum/501843-cb-karen-dillard-case-settled-no-cancelled-scores.html.

Questions

- Can you form a quick list of people who’d benefit because of this decision and others who’d end up on the losing side? Then, considering the situation globally and from a utilitarian perspective, what would need to be true for the settlement offer to be ethically recommendable?

-

As for those receiving the course for free—it’s probably safe to assume that their happiness increases. Something for nothing is good. But what about the students who still have to pay for the course? Some may be gladdened to hear that more students get the opportunity, but others will see things differently; they’ll focus on the fact that their parents are working and saving money to pay for the course, while others get it for nothing. Some of those who paid probably actually earned the money themselves at some disagreeable, minimum wage McJob. Maybe they served popcorn in the movie theater to one of those others who later on applied and got a hardship exemption.

- Starting from this frustration and unhappiness on the part of those who pay full price, can you form a utilitarian case against the settlement’s free classes?

- From a utilitarian perspective, could the College Board have improved the settlement by adding the stipulation that the settlement’s terms (and therefore the free classes) not be publicly disclosed?

- Once word got out, could a utilitarian recommend that the College Board lie or that it release a statement saying, “No free classes were part of the settlement”?

- There was talk about canceling the scores of those students who took the SAT after benefitting from the KDCP classes that offered access to the stolen exam booklets. The students and their parents protested vigorously, pointing out that they’d simply signed up for test prep, just like students all across the nation. They knew nothing about the theft and they presumably didn’t know they were practicing on questions that might actually appear on their exam day. From the perspective of rule utilitarianism, what’s the case for canceling their scores? From the perspective of act utilitarianism, what’s the case for reinstating the scores?

-

The College Board CEO makes around $830,000 a year.

- What is a utilitarian case for radically lowering his salary?

- If you were a utilitarian and you had the chance—and you were sure you wouldn’t get caught—would you steal the money from the guy’s bank account? Why or why not?

-

It could be that part of what the College Board hoped to gain through this settlement requiring free classes for the underprivileged was some positive publicity, some burnishing of their image as the good guys, the socially responsible company, the ones who do the right thing.

- Outline the case for this being an act of an altruistic company.

- Outline the case for this being an act of an egoistic company.

UFC

Source: Photo courtesy of Kaloozer, http://www.flickr.com/photos/kalooz/3942634378/.

Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) got off to a crushing start. In one of the earliest matches, Tank Abbott, a six-footer weighing 280 pounds, faced John Matua, who was two inches taller and weighed a whopping four hundred pounds. Their combat styles were as different as their sizes. Abbott called himself a pitfighter. Matua was an expert in more refined techniques: he’d honed the skills of wrestling and applying pressure holds. His skill—which was also a noble and ancient Hawaiian tradition—was the martial art called Kuialua.

The evening went poorly for the artist. Abbott nailed him with two roundhouses before applying a skull-cracking headbutt. The match was only seconds old and Matua was down and so knocked out that his eyes weren’t even closed, just glazed and staring absently at the ceiling. The rest of his body was convulsing. The referee charged toward the defenseless fighter, but Abbott was closer and slammed an elbow down on Matua’s pale face. Abbott tried to stand up and ram another, but the referee was now close enough to pull him away. As blood spurted everywhere and medics rushed to save the loser, Abbott stood above Matua and ridiculed him for being fat.David Plotz, “Fight Clubbed,” Slate, November 17, 1999, accessed May 15, 2011, http://www.slate.com/id/46344.

The tape of Abbott’s brutal skills and pitiless attitude shot through the Internet. He became—briefly—famous and omnipresent, even getting a guest appearance on the goofy, family-friendly sitcom Friends.

A US senator also saw the tape but reacted differently. Calling it barbaric and a human form of cockfighting, he initiated a crusade to get the UFC banned. Media executives were pressured to not beam the matches onto public TVs, and doctors were drafted to report that UFC fighters (like professional boxers) would likely suffer long-term brain damage. In the heat of the offensive, even diehard advocates agreed the sport might be a bit raw, and the UFC’s original motto—“There are no rules!”—got slightly modified. Headbutting, eye-gouging, and fish-hooking (sticking your finger into an opponent’s orifice and ripping it open) were banned.

No matter what anyone thinks of UFC, it convincingly demonstrates that blood resembles sex. Both sell, and people like to watch. The proof is that today UFC events are among the most viewed in the world, among the most profitable, and—this is the one part that hasn’t changed since the gritty beginning—among the most brutal.

Questions

-

Two of the common arguments against ultimate fighting—and the two main reasons the US senator argued to get the events banned—are the following:

- They’re brutal; UFC celebrates violence and hatred and injury, and therefore, it’s immoral.

- Besides the bumps, bruises, and broken bones—which usually heal up—the fighters also suffer long-term and incurable brain damage. Therefore, the sport is immoral even though it might be true that in their prime, the fighters make enough money to compensate the physical suffering endured in the octagon.

How could a utilitarian defend the UFC against these two criticisms?

- How could the concept of the utilitarian sacrifice apply to John Matua?

- How would a hedonistic utilitarian’s reaction to UFC differ from an idealistic utilitarian’s reaction? Is there anything at all in UFC that might convince an idealistic utilitarian to promote the sport as ethically positive?

- How could a proponent of monetized utilitarianism begin portioning up the experiences of Abbott, Matua, the UFC sponsors, and the spectators in order to construct a mathematical formula (like Ford did with the Pinto) to decide whether UFC should be banned?

- Think of UFC as a business, one compared to a biotech company that pioneers cutting-edge, life-saving drugs. Now, how would a utilitarian decide which one of these two companies was the more ethically respectable?

- Why might an altruist sign up to be a UFC fighter? Why might an egoist sign up to be a UFC fighter?

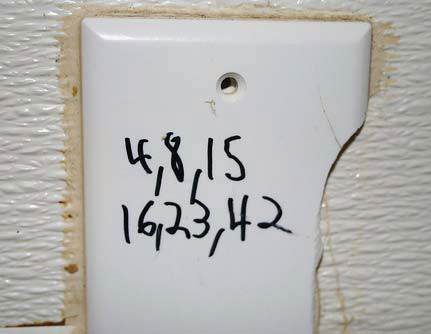

Lottery

Source: Photo courtesy of Alan Levine, http://www.flickr.com/photos/cogdog/81199624.

In her blog Majikthise, Lindsay Beyerstein writes, “State lotteries are often justified on the grounds that they raise money for social programs, especially those that target the neediest members of society. However, the poorest members of society tend to spend (and, by design lose) the most on lottery tickets. Some state lottery proceeds fund programs that benefit everyone, not just the poor. Often state lottery money is being systematically redistributed upward—from lotto players to suburban schools, for example.”Lindsay Beyerstein, “Lotteries as Regressive Taxes,” Majikthise (blog), January 23, 2006, accessed May 15, 2011, http://majikthise.typepad.com/majikthise_/2006/01/lotteries_as_re.html.

Questions

- How is the lottery an example of the utilitarian monster?

- How can you set yourself up to argue in favor of or against the ethical existence of the lottery in terms of monetized utilitarianism?

- Lotteries are about money and about fun—that is, even for the losers, there’s a benefit in the thrill of watching the numbers turn up. Could the case be made that, from a hedonistic utilitarian standpoint, the lottery is ethically recommendable because it serves the welfare not only of the winner but also of the millions of losers?

-

One of Lindsay Beyerstein’s concerns is that the lottery tends to redistribute money from the poor toward the rich.

- Does a utilitarian necessarily consider this redistribution unethical?

- What kinds of things would a utilitarian have to look into to decide whether the inverse Robin Hooding is necessarily a bad thing?

- The lotteries under discussion here are run by states, and Lindsay Beyerstein is not a big fan. She calls these lotteries “a tax on idiocy” meaning, presumably, that people are just throwing their money away every time they buy a ticket. Now, one of the arguments in favor of egoism as an ethical stance is that no one knows what makes each of us happy better than each of us. So, it follows, we should all just try to get what we want and leave other people alone. How can this view of egoism be fashioned to respond to the idea that the lottery is a tax on idiocy?

Honest Tea

Source: Photo courtesy of Arnold Gatilao, http://www.flickr.com/photos/arndog/1210077306/.

Seth Goldman founded Honest Tea in 1998. He calls himself the TeaEO (as opposed to CEO) and his original product was a bottled tea drink with no additives beyond a bit of sugar. Crisp and natural—that was the product’s main selling point. It wasn’t the only selling point, though. The others aren’t in the bottle, they’re in the company making it. Honest Tea is a small enterprise composed of good people. As the company website relates, “A commitment to social responsibility is central to Honest Tea’s identity and purpose. The company strives for authenticity, integrity and purity, in our products and in the way we do business.…Honest Tea seeks to create honest relationships with our employees, suppliers, customers and with the communities in which we do business.”“Our Mission,” Honest, accessed May 15, 2011, http://www.honesttea.com/mission/about/overview.

Buy Honest Tea, the message is, because the people behind it are trustworthy; they are the kind of entrepreneurs you want to support.

The mission statement also relates that when Honest Tea gives business to suppliers, “we will attempt to choose the option that better addresses the needs of economically disadvantaged communities.”“Our Mission,” Honest, accessed May 15, 2011, http://www.honesttea.com/mission/about/overview. They’ll give the business, for example, to the company in a poverty-stricken area because, they figure, those people really need the jobs. Also, and to round out this socially concerned image, the company promotes ecological (“sustainability”) concerns and fair trade practices: “Honest Tea is committed to the well-being of the folks along the value chain who help bring our products to market. We seek out suppliers that practice sustainable farming and demonstrate respect for individual workers and their families.”“Our Mission,” Honest, accessed May 15, 2011, http://www.honesttea.com/mission/about/overview.

Summing up, Honest Tea provides a natural product, helps the poor, treats people with respect, and saves the planet. It’s a pretty striking corporate profile.

It’s also a profile that sells. It does because when you hand over your money for one of their bottles, you’re confident that you’re not fattening the coffers of some moneygrubbing executive in a New York penthouse who’d lace drinks with chemicals or anything else that served to raise profits. For many consumers, that’s good to know.

Honest Tea started selling in Whole Foods and then spread all over, even to the White House fridges because it’s a presidential favorite. Revenues are zooming up through the dozens of millions. In 2008, the Coca-Cola Company bought a 40 percent share of Honest Tea for $43 million. It’s a rampantly successful company.

Featured as part of a series in the Washington Post in 2009, the company’s founder, Seth Goldman, was asked about his enterprise and his perspective on corporate philanthropy, meaning cash donations to good causes. Goldman said, “Of course there’s nothing wrong with charity, but the best way for companies to become good citizens is through the way they operate their business.” Here are two of his examples:“On Leadership: Seth Goldman,” Washington Post, accessed May 15, 2011, http://views.washingtonpost.com/leadership/panelists/2009/11/the-biggest-dollars.html.

- Switching from Styrofoam to postconsumer waste might help a packaging company make a more meaningful contribution to sustainability than a token donation to an environmental nonprofit.

- Investing in a local production facility or even a community bank could help support a local economy more effectively than a donation to a nearby jobs program.

Organizations in the economic world, Goldman believes, can do the most good by doing good themselves as opposed to doing well (making money) and then outsourcing their generosity and social responsibility by donating part of their profits to charities. That may be true, or it may not be, but it’s certain that Goldman is quite good at making the case. He’s had a lot of practice since he’s outlined his ideas not just in the Post but in as many papers and magazines as he can find. Honest Tea’s drinks are always featured prominently in these flattering articles, which are especially complimentary when you consider that Honest Tea doesn’t have to pay a penny for them.

Questions

-

Make the case that Seth Goldman founded Honest Tea as an expression of his utilitarian ethics.

- What kinds of people are affected by the Honest Tea organization? Which groups might benefit from Honest Tea and how? Which groups might not benefit?

- Would this be a hedonistic or idealistic utilitarianism? Why?

- Would it be possible to construe Honest Tea within a framework of monetized utilitarianism?

- Would this be a soft or hard utilitarianism?

-

Make the case that Seth Goldman founded Honest Tea as an expression of his ethical altruism.

- Altruists serve the welfare of others. How does Honest Tea serve people’s welfare?

- What would have to be true about Goldman in terms of his particular abilities and skills for this enterprise to fall under the heading of altruism?

- Does Goldman sound more like a personal or an impersonal altruist?

-

Make the case that Seth Goldman founded Honest Tea as an expression of his ethical egoism.

- What are some of the benefits Goldman could derive from Honest Tea?

- Before running Honest Tea, Goldman was a big-time mutual fund manager. What kind of benefits could Honest Tea have offered that he couldn’t find in the world of finance?

- Does Goldman sound more like a personal or an impersonal egoist?

- In the real world, does it make any difference whether Goldman does enlightened egoism or cause egoism?

- In this case study, two kinds of drink manufacturers are contrasted: Honest Tea and the hypothetical drink company run by some mercenary businessman lacing drinks with bad chemicals to maximize profits. Looking at this contrast, how could a defender of egoism claim that the best way for healthy drinks to make their way into the general public’s hands (in the medium and long term, anyway) is for Goldman and the mercenary businessman and everyone else to all be egoists?

- Assume that Seth Goldman is a cause egoist, someone faking concern for the general welfare in order to provide for his own happiness and pleasure. How could the concept of the invisible hand be introduced to make the claim that Goldman is actually doing more good for the general welfare than he would if he were a utilitarian or even an altruist?

Your Business

Source: Photo courtesy of Paul Sapiano, http://www.flickr.com/photos/peasap/935756569.

Think about something you do with passion or expertise—a dish you like to cook and eat, a sport you play, any unique skill or ability you’ve developed—and figure out a way to turn it into a small business. For example, you like baking cookies, so you open a bake shop, or you like hockey and could imagine an improved stick to invent and market.

Questions

- If your business is like most others, you’re going to need some money to get it up and going, more money than you’ve got right now. That means you’ll need to find a partner for your venture, someone to help you get the cash together and then run things afterward. Would you prefer a utilitarian, an altruist, or an egoist for your partner? Why?

- Do you think the invisible hand would be in effect for your business? Just by trying to make money, do you imagine you’d end up improving people’s lives? If this business works, is it even possible that you’d help others more than you would by volunteering time for a charity organization? Elaborate.

-

Assume that doing good in society and not just doing well (making money) is important to you. Within the business you have in mind, with which of these three options do you suspect you’d accomplish more general good?

- Just making money and trusting the invisible hand to take care of the rest

- Making money and donating part of it to charity—that is, to people specialized in serving the general welfare

- Attempting to do good within your business by, for example, buying recycled materials or by paying wages slightly above what people could get for the same work at other companies

- Is there a potential cause egoism angle to your business? Could you set it up to make it seem like the reason you’re running your enterprise is to help others when really you’re just trying to make money? For a consequentialist, is there anything wrong with that?