This is “Activists and Strict Constructionists”, section 2.2 from the book Business and the Legal and Ethical Environment (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.2 Activists and Strict Constructionists

Learning Objectives

- Explore the strict constructionist, or originalist, judicial philosophy.

- Explore the judicial activist philosophy.

- Learn about the modern origin of the divide between these two philosophies.

- Examine the evolution of the right to privacy and how it affects judicial philosophy.

- Explore the biographies of the current Supreme Court justices.

In the early years of the republic, judges tended to be much more political than they are today. Many were former statesmen or diplomats and considered being a judge to be a mere extension of their political activities. Consider, for example, the presidential election of 1800 between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Even by today’s heated standards of presidential politics, the 1800 election was bitter and partisan. When Jefferson won, he was in a position of being president at a time when not a single federal judge in the country came from his political party. Jefferson was extremely wary of judges, and when the Supreme Court handed down the Marbury v. Madison decision in 1803 declaring the Supreme Court the ultimate interpreter of the Constitution’s meaning, Jefferson wrote that “to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions is a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.”Thomas Jefferson to William C. Jarvis, 1820, in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert Ellery Bergh, Memorial Edition (Washington, DC: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903–4), 15:277, quoted in Eyler Robert Coates Sr., “18. Judicial Review,” Thomas Jefferson on Politics & Government: Quotations from the Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 1999, http://etext.virginia.edu/jefferson/quotations/jeff1030.htm (accessed September 24, 2010). A few years later, the first justice to be impeached, Samuel Chase, was accused of being overly political. His impeachment (and subsequent acquittal) started a trend toward nonpartisanship and political impartiality among judges. Today, judges continue this tradition by exercising impartiality in cases before them. Nonetheless, charges of political bias continue to be levied against judges at all levels.

In truth, the majority of a judge’s work has nothing to do with politics. Even at the Supreme Court level, most of the cases heard involve conflicts among circuit courts of appeals or statutory interpretation. In a small minority of cases, however, federal judges are called on to interpret a case involving religion, race, or civil rights. In these cases, judges are guided sometimes by nothing more than their own interpretation of case law and their own conscience. This has led some activists to claim that judges are using their positions to advance their own political agendas.

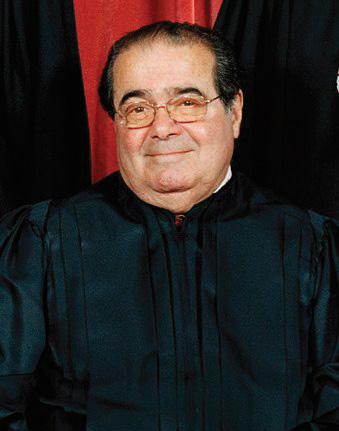

In general terms, judges are thought to fall into one of two ideological camps. On the politically conservative right, judges are described as either strict constructionistsAlso known as originalists. Politically conservative judges who adhere to the view that the Constitution should be interpreted in light of its original meaning when it was adopted and that new rights should be granted by the legislative process rather than through judicial review. or originalistsJurists who subscribe to original meaning.. Judges who adhere to this philosophy believe that social change is best left to the politically elected branches of government. The role of judges is therefore to strictly interpret the Constitution, and nothing more. Strict constructionists also believe that the Constitution contains the complete list of rights that Americans enjoy and that any right not listed in the Constitution does not exist and must be earned legislatively or through constitutional amendment. Judges do not have the power to “invent” a new right that does not exist in the Constitution. These judges believe in original meaningThe view that the Constitution should be interpreted in light of what the Founding Fathers meant when they wrote the document., which means interpreting the Constitution as it was meant when it was written, as opposed to how society would interpret the Constitution today. Strict constructionists believe that interpreting new rights into the Constitution is a dangerous exercise because there is nothing to guide the development of new rights other than a judge’s individual conscience. Justice Antonin Scalia, appointed by Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court in 1984, embodies the modern strict constructionist.

Hyperlink: Justice Antonin Scalia

Figure 2.7 Justice Antonin Scalia

Source: Photo courtesy of Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Antonin_Scalia,_SCOTUS_photo_portrait.jpg.

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/24/60minutes/main4040290.shtml

In 2008, Justice Antonin Scalia (Figure 2.7 "Justice Antonin Scalia") sat down with 60 Minutes to discuss a new book he wrote and his originalist judicial philosophy. Click the link to watch a portion of this fascinating interview with one of the most powerful judges in the country.

On the politically liberal left are judges who are described as activist. Judicial activistsJudges who adhere to the view that the Constitution is a living document that should adapt and change with the times. believe that judges have a role in shaping a “more perfect union” as described in the Constitution and that therefore judges have the obligation to seek justice whenever possible. They believe that the Constitution is a “living document” and should be interpreted in light of society’s needs, rather than its historical meaning. Judicial activists believe that sometimes the political process is flawed and that majority rule can lead to the baser instincts of humanity becoming the rule of law. They believe their role is to safeguard the voice of the minority and the oppressed and to deliver the promise of liberty in the Constitution to all Americans. Judicial activists believe in a broad reading of the Constitution, preferring to look at the motivation, intent, and implications of the Constitution’s safeguards rather than merely its words. Judicial activism at the Supreme Court was at its peak in the 1960s, when Chief Justice Earl Warren led the Court in breaking new ground on civil rights protections. Although a Republican, and nominated by Republican President Eisenhower, Earl Warren became a far more activist judge than anyone anticipated once on the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Warren led the Court in the desegregation cases in the 1950s, including the one affecting the Little Rock Nine. The “Miranda”Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1969). warnings—familiar to nearly every American who has ever seen a police show or movie—come from Chief Justice Warren, as does the fact that anyone who cannot afford an attorney has the right to publicly funded counsel in most criminal cases.

Figure 2.8 President Franklin Roosevelt

Source: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress, http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c17121.

The modern characterization of judges as politically motivated can be traced to the Great Depression. Against cataclysmic economic upheaval, Americans voted for Franklin D. Roosevelt (Figure 2.8 "President Franklin Roosevelt") in record numbers, and they delivered commanding majorities in both the Senate and House of Representatives to his Democratic Party. President Roosevelt vowed to alter the relationship between the people and their government to prevent the sort of destruction and despair wreaked by the Depression. The centerpiece of his action plan was the New Deal, a legislative package that rewrote the role of government, vastly increasing its size and its role in private commercial activity. The New Deal brought maximum working hours, the minimum wage, mortgage assistance, economic stimulus, and social safety nets such as Social Security and insured bank deposits. Although the White House and the Congress were in near-complete agreement on the New Deal, the Supreme Court was controlled by a slim majority known as the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” because of their dire warnings of the consequences of economic regulation. Three justices known as the “Three Musketeers”—Justice Brandeis, Justice Cardozo, and Justice Stone—opposed the Four Horsemen. In the middle sat two swing votes. The Four Horsemen initially prevailed, and one by one, pieces of President Roosevelt’s New Deal were struck down as unconstitutional reaches of power by the federal government. Frustrated, President Roosevelt devised a plan to alter the makeup of the Supreme Court by increasing the number of judges and appointing new justices. The “court-packing plan” was never implemented due to the public’s reaction, but nonetheless, the swing votes on the Supreme Court switched their votes and began upholding New Deal legislation, leading some historians to label their move the “switch in time that saved Nine.” During the public debate over the Supreme Court’s decisions on the New Deal, the justices came under constant attack for being politically motivated. The loudest criticism came from the White House.

Hyperlink: Fireside Chats

http://millercenter.org/scripps/archive/speeches/detail/3309

One of the hallmarks of FDR’s presidency was his use of the radio to reach millions of Americans across the country. He regularly broadcast his “fireside chats” to inform and lobby the public. In this link, President Roosevelt complains bitterly about the Supreme Court, claiming that “the Court has been acting not as a judicial body, but as a policy-making body.” Do modern politicians make the same accusation?

The abortion debate is a good example of the politically charged atmosphere surrounding modern judicial politics. Strict constructionists decry Roe v. Wade as an extremely activist decision and bemoan the fact that in a democracy, no one has ever had the chance to vote on one of the most socially controversial and divisive issues of our time. Roe held that a woman has a right to privacy and that her right to privacy must be balanced against the government’s interest in preserving human life. Within the first trimester of her pregnancy, her right to privacy outweighs governmental intrusion. Since there is no right to privacy mentioned in the Constitution, strict constructionists believe that Roe has no constitutional foundations to stand on.

Roe did not, however, declare that a right to privacy exists in the Constitution. A string of cases before Roe established that right. In 1965 the Supreme Court overturned a Connecticut law prohibiting unmarried couples from purchasing any form of birth control or contraceptive.Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). The Court reasoned that the First Amendment has a “penumbra of privacy” that must include the right for couples to choose if and when they want to have children. Two years later, the Supreme Court found a right to privacy in the due process clause when it declared laws prohibiting mixed-race marriages to be unconstitutional.Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967). As a result of these decisions and others like them, the phrase “right to privacy” today is widely accepted as a form of litmus test for whether a judge (or judicial candidate) is a strict constructionist or activist.

Video Clip: A Question of Ethics: The Right to Privacy and Confirmation Hearings

(click to see video)Since federal judges are appointed for lifetime, the turnover rate for federal judgeships is low. Recently, the Supreme Court went through an eleven-year period without any changes in membership. In the last five years, however, four new justices have joined the Court. First, John Roberts was nominated by George W. Bush in 2005 to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. President Bush did not have the opportunity to nominate anyone to the Supreme Court during his first term as president, and John Roberts’s nomination was viewed widely as a smart move to place on the Court a young, smart, and popular judge with solid Republican credentials. (Roberts began his legal career as an attorney with the Reagan administration.) Before the Senate could confirm Roberts, however, Chief Justice Rehnquist died of thyroid cancer while still in office. President Bush withdrew his nomination and renominated John Roberts as chief justice, which the Senate confirmed. President Bush then began looking for a nominee to replace Justice O’Connor. His first nominee was a close personal friend, Harriet Miers. Selecting Miers allowed him to replace a woman with a woman, something important to First Lady Laura Bush. More importantly, the president felt that Miers, a born-again Christian, would comfortably establish herself as a solid judicial conservative. Others in the Republican Party, however, were nervous about her nomination given her lack of judicial experience. (Miers had never been a judge.) Keen to avoid another situation in which a conservative president nominated a judge who turned out liberal, as was the case with President George H. W. Bush’s nomination of David Souter, key lawmakers put enough pressure on Miers that she withdrew her nomination. For his second nominee, President George W. Bush selected Samuel Alito, a safe decision given Alito’s prior judicial record. Although he has been on the Court for only a few years, most legal observers believe Alito’s nomination is critical in moving the Court to the political right, as Alito has demonstrated himself to be more ideological in his opinions than the pragmatic O’Connor. In his first term as president, President Barack Obama has had the opportunity to name two justices to the Supreme Court: Sonia Sotomayor in 2009 to replace David Souter and Elena Kagan in 2010 to replace John Stevens. Both nominations are widely regarded as not moving the Court too much in either direction in terms of activism or originalism. There are now three women on the Supreme Court, a historical record.

Hyperlink: Biographies of the Current Supreme Court Justices

http://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographiescurrent.pdf

The Supreme Court today is more diverse than it ever has been throughout its history. The hardworking men and women of the Court command respect from the legal community both in the United States and abroad. Click the link to explore their biographies.

Key Takeaways

Judicial conservatives, also known as originalists or strict constructionists, believe that the Constitution should be interpreted strictly, in light of its original meaning when it was written. They believe that societal change, especially the creation of new civil rights, should come from the political process rather than the judicial process. Judicial liberals, also known as judicial activists, believe that judges have a role to play in shaping a more perfect union. They believe that the outcome of a case is paramount over other considerations, including past precedent. Judicial activists are more likely to find new civil rights in the Constitution, which they believe should be broadly interpreted in light of modern society’s needs. The modern fight over judicial conservatives and judicial liberals began with FDR’s New Deal and his court-packing plan and continues to this day. The right to privacy is a good example of the difference between judicial conservatives and judicial liberals, and it is seen as a test to determine what philosophy a judge subscribes to. After a long period of stability, membership in the Supreme Court has changed substantially in the last three years with three new members. The Court remains closely divided between judicial conservatives and judicial liberals, with conservatives poised to control the Court’s direction. Justice Anthony Kennedy, a moderate conservative, remains the key swing vote on the Supreme Court.

Exercises

- Read Justice Stewart’s dissent in the Griswold case here: http://www4.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0381_0479_ZD1.html. Although he believes Connecticut’s law is “uncommonly silly,” he nonetheless believes that it’s not unconstitutional. Do you think that judges have an obligation to overturn “uncommonly silly” laws?

- Modern judicial confirmation hearings have been described as an intricate dance between nominees and Senators, with the nominees giving broad scripted answers that reveal little about their actual judicial philosophy. Do you agree with this characterization? Do you think any changes should be made to the confirmation process?

- If you were president, what characteristics would you look for in nominating federal judges?

- If an elected legislature refuses to grant citizens a right to privacy, do you believe it is appropriate for the courts to do so? Why or why not?

- If a president believes that the Court has reached the wrong result, should the president be able to change the Court by increasing its numbers or forcing early retirement?