This is “Issuing and Accounting for Preferred Stock and Treasury Stock”, section 16.3 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

16.3 Issuing and Accounting for Preferred Stock and Treasury Stock

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the difference between preferred stock and common stock.

- Discuss the distribution of dividends to preferred stockholders.

- Record the issuance of preferred stock.

- Provide reasons for a corporation to spend its money to reacquire its own capital stock as treasury stock.

- Account for the purchase and resale of treasury stock when both gains and losses occur.

Differentiating Preferred Stock from Common Stock

Question: Some corporations also issue a second type of capital stock referred to as preferred stockA capital stock issued by some companies that has one or more specified preferences over common shareholders, usually in the form of cash dividends.. Approximately 5–15 percent of the corporations in the United States have preferred stock outstanding but the practice is especially prevalent in certain industries. How is preferred stock different from common stock?

Answer: Preferred stock is another version of capital stock where the rights of those owners are set by the contractual terms of the stock certificate rather than state law. In effect, common stockholders voluntarily surrender one or more of their legal rights in hopes of enticing additional investors to contribute money to the corporation. For common stockholders, preferred stock is often another possible method of achieving financial leverage in a manner similar to using money raised from bonds and notes. If the resulting funds can be used to generate more profit than the dividends paid on the preferred stock, the residual income for the common stock will be higher.

The term “preferred stock” comes from the preference that is conveyed to these owners. They are being allowed to step in front of common stockholders when specified rights are applied. A wide variety of such benefits can be assigned to the holders of preferred shares, including additional voting rights, assured representation on the board of directors, and the right to residual assets if the company ever liquidates.

By far the most typical preference is to cash dividends. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, all common stockholders are entitled to share proportionally in any dividend distributions. However, if a corporation issues preferred stock with a stipulated dividend, that amount must be paid before any money is conveyed to the owners of common stock. No dividend is ever guaranteed, not even one on preferred shares. A dividend is only legally required if declared by the board of directors. But, if declared, the preferred stock dividend normally must be paid before any common stock dividend. Common stock is often referred to as a residual ownership because these shareholders are entitled to all that remains after other claims have been settled including those of preferred stock.

The issuance of preferred stock is accounted for in the same way as common stock. Par value, though, often serves as the basis for stipulated dividend payments. Thus, the par value listed for a preferred share frequently approximates fair value. To illustrate, assume a corporation issues ten thousand shares of preferred stock. A $100 per share par value is printed on each stock certificate. If the annual dividend is listed as 4 percent, cash of $4 per year ($100 par value × 4 percent) must be paid on preferred stock before any distribution is made on common stock.

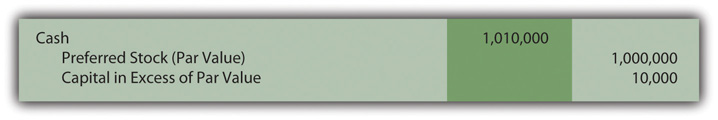

If ten thousand shares of this preferred stock are each issued for $101 in cash ($1,010,000 in total), the company records the journal entry shown in Figure 16.5 "Issue Ten Thousand Shares of $100 Par Value Preferred Stock for $101 per Share".

Figure 16.5 Issue Ten Thousand Shares of $100 Par Value Preferred Stock for $101 per Share

For recording purposes, companies often establish separate “capital in excess of par value” accounts—one for common stock and one for preferred stock. Those amounts are then frequently combined in reporting the balances within stockholders’ equity.

Test Yourself

Question:

The Gatellan Company wants to acquire a building worth $2 million from Alice Wilkinson. The company does not have sufficient cash and does not want to take out a loan so it offers to issue 90,000 shares of its $1 par value common stock in exchange for the building. Wilkinson wants more assurance of receiving a dividend each year and asks for 18,000 shares of the company’s $100 par value preferred stock paying an annual dividend rate of 5 percent. Eventually, the parties come to an agreement and the Gatellan Company records capital in excess of par value of $200,000. Which of the following happened?

- Gatellan issued the common stock but it had no known fair value.

- Gatellan issued the common stock and it had a $20 per share fair value.

- Gatellan issued the preferred stock and it had no known fair value.

- Gatellan issued the preferred stock and it had a $102 per share fair value.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: Gatellan issued the preferred stock and it had no known fair value.

Explanation:

In a, the asset is recorded at $2 million, the stock is its $90,000 par value, and the capital in excess is $1.91 million. In b, the asset is recorded at $1.8 million, the stock is its $90,000 par value, and the capital in excess is $1.71 million. In c, the asset is recorded at $2 million, the stock is its $1.8 million par value, and the capital in excess is $200,000. In d, the asset is recorded at $1,836,000, the stock is its $1.8 million par value, and the capital in excess is $36,000.

The Acquisition of Treasury Stock

Question: An account called treasury stockIssued shares of a corporation’s own stock that have been reacquired; balance is shown within the stockholders’ equity section of the balance sheet as a negative amount unless the shares are retired (removed from existence). is often found near the bottom of the shareholders’ equity section of a balance sheet. Treasury stock represents issued shares of a corporation’s own stock that have been reacquired. For example, the September 30, 2011, balance sheet for Viacom Inc. reports a negative balance of over $8.2 billion identified as treasury stock.

An earlier story in the Wall Street Journal indicated that Viacom had been buying and selling its own stock for a number of years: “The $8 billion buyback program would enable the company to repurchase as much as 13 percent of its shares outstanding. The buyback follows a $3 billion stock-purchase program announced in 2002, under which 40.7 million shares were purchased.”Joe Flint, “Viacom Plans Stock Buy Back, Swings to Loss on Blockbuster,” The Wall Street Journal, October 29, 2004, B-2.

Why does a company voluntarily give billions of dollars back to stockholders in order to repurchase its own stock? That is a huge amount of money leaving the company. Why not invest these funds in inventory, buildings, investments, research and development, and the like? Why does a corporation buy back its own shares as treasury stock?

Answer: Numerous possible reasons exist to justify spending money to reacquire an entity’s own stock. Several of these strategies are rather complicated and a more appropriate topic for an upper-level finance course. However, an overview of various ideas should be helpful in understanding the rationale for such transactions.

- As a reward for service, businesses often give shares of their stock to key employees or sell shares to them at a relatively low price. In some states, using unissued shares for such purposes is restricted legally. The same rules do not apply to shares that have been reacquired. Thus, some corporations acquire treasury shares to have available as needed for compensation purposes.

- Acquisition of treasury stock can be used as a tactic to push up the market price of a company’s stock in order to please the remaining stockholders. Usually, a large scale repurchase (such as made by Viacom) indicates that management believes the stock is undervalued at its current market price. Buying treasury stock reduces the supply of shares in the market and, according to economic theory, forces the price to rise. In addition, because of the announcement of the repurchase, outside investors often rush in to buy the stock ahead of the expected price increase. The supply of shares is decreased while demand is increased. Stock price should go up. Not surprisingly, current stockholders often applaud a decision to buy treasury shares as they anticipate a jump in their investment values.

- Corporations can also repurchase shares of stock to reduce the risk of a hostile takeover. If another company threatens to buy sufficient shares to gain control, the board of directors of the target company must decide if acquisition is in the best interest of the stockholders.If the board of directors does agree to the purchase of the corporation by an outside party, the two sides then negotiate a price for the shares as well as any other terms of the acquisition. If not, the target might attempt to buy up shares of its own stock in hopes of reducing the number of owners in the market who are willing to sell their shares. Here, repurchase is a defensive strategy designed to make the takeover more difficult to accomplish. Plus, as mentioned previously, buying back treasury stock should drive the price up, making purchase more costly for the predator.

Reporting the Purchase of Treasury Stock

Question: To illustrate the financial reporting of treasury stock, assume that the Chauncey Company has been in business for over twenty years. During that time, the company has issued ten million shares of its $1 par value common stock at an average price of $3.50 per share. The company now reacquires three hundred thousand of these shares for $4 each. How is the acquisition of treasury stock reported?

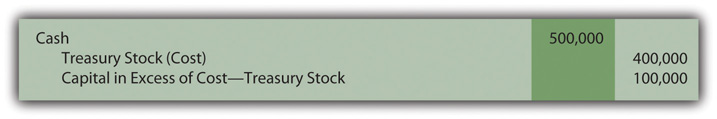

Answer: Under U.S. GAAP, several methods are allowed for reporting the purchase of treasury stock. Most companies use the cost method because of its simplicity. As shown in Figure 16.6 "Purchase of Three Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock at a Cost of $4 Each", the acquisition of these shares is recorded by Chauncey at the $1.2 million cost (300,000 shares at $4 each) that was paid.

Figure 16.6 Purchase of Three Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock at a Cost of $4 Each

Because the money spent on treasury stock represents assets that have left the business, this balance is shown within stockholders’ equity as a negative, reflecting a decrease in net assets instead of an increase.

Except for possible legal distinctions, treasury stock held by a company is the equivalent of unissued stock. The shares do not receive dividends and have no voting privileges.

Reporting the Reissuance of Treasury Stock above Cost

Question: Treasury shares can be held by a corporation forever or eventually reissued at prices that might vary greatly from original cost. If sold for more than cost, is a gain recognized? If sold for less, is a loss reported? What is the impact on a corporation’s financial statements if treasury stock shares are reissued?

To illustrate, assume that Chauncey Company subsequently sells one hundred thousand shares of its treasury stock (shown in Figure 16.6 "Purchase of Three Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock at a Cost of $4 Each") for $5.00 each. That is $1.00 more than these shares had cost to reacquire. Is this excess reported by Chauncey as a gain on its income statement?

Answer: As discussed previously, transactions in a corporation’s own stock are considered expansions and contractions of the ownership and never impact reported net income. The buying and selling of capital stock are transactions viewed as fundamentally different from the buying and selling of assets such as inventory and land. Therefore, no gains and losses are recorded in connection with treasury stock. As shown in Figure 16.7 "Sale of One Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock Costing $4 Each for $5 per Share", an alternative reporting must be constructed.

Figure 16.7 Sale of One Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock Costing $4 Each for $5 per Share

The “capital in excess of cost-treasury stock” is the same type of account as the “capital in excess of par value” that was recorded in connection with the issuance of both common and preferred stocks. Within stockholders’ equity, these individual accounts can be grouped into a single balance or reported separately.

Reporting the Reissuance of Treasury Stock below Cost

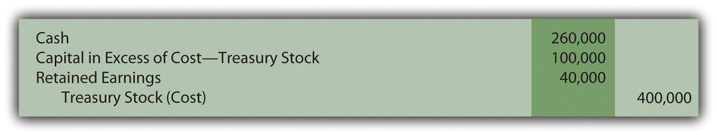

Question: The first group of treasury shares was reissued for more than cost. Assume that Chauncey subsequently sells another one hundred thousand of treasury shares, but this time for only $2.60 each. The proceeds in this transaction are below the acquisition cost of $4 per share. What recording is made if treasury stock is sold at the equivalent of a loss?

Answer: Interestingly, the reissuance of treasury stock for an amount below cost is a transaction not well covered in U.S. GAAP. Authoritative rules fail to provide a definitive rule for reporting such reductions except that stockholders’ equity is decreased with no direct impact recorded in net income. Absolute rules are not always available in U.S. GAAP.

The most common approach seems to be to first remove any capital in excess of cost recorded by the reissuance of earlier shares of treasury stock at above cost. If that balance is not large enough to absorb the entire reduction, a decrease is then made in retained earnings as shown in Figure 16.8 "Sale of One Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock Costing $4 Each for $2.60 per Share". The $100,000 balance in capital in excess of cost-treasury stock was created in the previous reissuance illustrated in Figure 16.7 "Sale of One Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock Costing $4 Each for $5 per Share".

Figure 16.8 Sale of One Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock Costing $4 Each for $2.60 per Share

One outcome of this handling should be noted. In earlier chapters of this textbook, “retained earnings” was defined as a balance equal to all income reported over the life of a business less all dividend distributions to the owners. Apparently, this definition is not correct in every possible case. In Figure 16.8 "Sale of One Hundred Thousand Shares of Treasury Stock Costing $4 Each for $2.60 per Share", the retained earnings balance is also reduced as a result of a stock transaction where a loss occurred that could not otherwise be reported.

Test Yourself

Question:

Several years ago, Ashkroft Inc. issued 800,000 shares of $2 par value stock for $3 per share in cash. Early in the current year, Ashkroft repurchases 100,000 of these shares at $8 per share. A month later, 40,000 of these treasury shares are sold back to the public at $10 per share. What is the total impact on reported shareholders’ equity of these transactions?

- $1,920,000 increase

- $2,000,000 increase

- $2,280,000 increase

- $2,420,000 increase

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $2,000,000 increase.

Explanation:

The initial issuance of stock increases net assets by $2.4 million (800,000 shares × $3). The purchase of treasury stock reduces net assets by $800,000 (100,000 shares × $8). The reissuance of a portion of the treasury stock increases net assets by $400,000 (40,000 shares × $10). The individual account balances have not been computed here but the overall increase in shareholders’ equity is $2 million ($2.4 million less $800,000 plus $400,000).

Test Yourself

Question:

Several years ago, the Testani Corporation issued 800,000 shares of $2 par value stock for $3 per share in cash. Early in the current year, Testani repurchases 100,000 shares at $8 per share. A month later, 40,000 of these shares are sold back to the public at $10 per share. Several weeks later, after a drop in market price, 50,000 more shares of the treasury stock were reissued for $5 per share. What is the overall impact on reported retained earnings of the reissuance of the 90,000 shares of treasury stock?

- No effect

- $50,000 reduction

- $70,000 reduction

- $90,000 reduction

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: $70,000 reduction.

Explanation:

The first batch of 40,000 shares of treasury stock was sold at $2 above cost, creating a capital in excess of cost account of $80,000. The second batch of 50,000 shares was sold at $3 below cost or $150,000 in total. In recording this second reissuance, the $80,000 capital in excess of cost is first removed entirely with the remaining $70,000 shown as a decrease in retained earnings.

Key Takeaway

A corporation can issue preferred stock as well as common stock. Preferred shares are given specific rights that come before those of common stockholders. Frequently, these rights involve the distribution of dividends. A set amount is often required to be paid before common stockholders can receive any dividends. After issuance, capital stock shares can be bought back by a company from its investors for a number of reasons. For example, repurchase might be carried out in hopes of boosting the stock price. These shares are usually reported at cost and referred to as treasury stock. In acquiring such shares, money flows out of the company so the account appears as a negative balance within stockholders’ equity. When reissued above cost, the treasury stock account is reduced and capital in excess of cost is recognized. To record a loss, any previous capital in excess of cost balance is removed followed by a possible reduction in retained earnings. Net income is not impacted by a transaction in a company’s own stock.