This is “Determining Historical Cost and Depreciation Expense”, section 10.2 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

10.2 Determining Historical Cost and Depreciation Expense

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Make use of the guiding accounting rule to ascertain which costs are capitalized and which are expensed when acquiring property and equipment.

- List the variables that impact the amount of depreciation to be expensed each period in connection with the property and equipment owned by a company.

- Recognize that the straight-line method for assigning depreciation predominates in practice but any system that provides a rational approach can be used to create a pattern for this cost allocation.

Assets Classified as Property and Equipment

Question: Businesses hold numerous types of assets, such as receivables, inventory, cash, investments, and patents. Proper classification is important for the clarity of the reported information. In preparing a balance sheet, what requirements must be met for an asset to be included as part of a business’s property and equipment?

Answer: To be classified within the property and equipment category, an asset must have tangible physical substance and be expected to help generate revenues for longer than a single year. In addition, it must function within the normal operating activities of the business. However, it cannot be held for immediate resale, like inventory.

A building used as a warehouse and machinery operated in the production of inventory both meet these characteristics. Other examples include computers, furniture, fixtures, and equipment. Conversely, land acquired as a future plant site and a building held for speculative purposes are both classified as investments (or, possibly, “other assets”) rather than as property and equipment. Neither of these assets is being used at the current time to help generate operating revenues.

Determining Historical Cost

Question: The accounting basis for reporting property and equipment is historical cost. What amounts are included in determining the cost of such assets? Assume, for example, that Walmart purchases a parcel of land and then constructs a retail store on the site. Walmart also buys a new cash register to use at this outlet. Initially, such assets are reported at cost. For property and equipment, how is historical cost defined?

Answer: In the previous chapter, the cost of a company’s inventory was identified as the sum of all normal and necessary amounts paid to get the merchandise into condition and position to be sold. Property and equipment are not bought for resale, so this rule must be modified slightly. All expenditures are included within the cost of property and equipment if the amounts are normal and necessary to get the asset into condition and position to assist the company in generating revenues. That is the purpose of assets: to produce profits by helping to create the sale of goods and services.

Land can serve as an example. When purchased, the various normal and necessary expenditures made by the owner to ready the property for its intended use are capitalized to arrive at reported cost. These amounts include payments made to attain ownership as well as any fees required to obtain legal title. If the land is acquired as a building site, money spent for any needed grading and clearing is also included as a cost of the land rather than as a cost of the building or as an expense. These activities readied the land for its ultimate purpose.

Buildings, machinery, furniture, equipment and the like are all reported in a similar fashion. For example, the cost of constructing a retail store includes money spent for materials and labor as well as charges for permits and any fees paid to architects and engineers. These expenditures are all normal and necessary to get the structure into condition and position to help generate revenues.

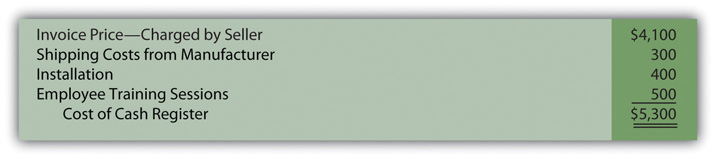

As another example, the cost of a new cash register might well include shipping charges, installation fees, and training sessions to teach employees to use the asset. These costs all meet the criterion for capitalization. They are normal and necessary payments to permit use of the equipment for its intended purpose. Hence, a new cash register bought at a price of $4,100 might actually be reported as an asset by its owner at $5,300 as follows:

Figure 10.1 Capitalized Cost of Equipment

Test Yourself

Question:

On January 1, Year One, a company buys a plot of land and proceeds to construct a warehouse on that spot. One specific cost of $10,000 was normal and necessary to the acquisition of the land. However, by accident, this charge was capitalized within the building account. Which of the following statements is not correct?

- The building account will always be overstated by $10,000.

- The land will be understated by $10,000 as long as the company owns it.

- For the next few years, net income will be understated.

- For the next few years, expenses will be overstated.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice a: The building account will always be overstated by $10,000.

Explanation:

A building has a finite life. During its use, the cost is systematically moved to expense. The $10,000 misstatement here overstates the building balance. However, the gradual expensing of that amount through depreciation reduces the overstatement over time. This error inflates the amount of expense reported each year understating net income. The land does not have a finite life. Therefore, its cost is not expensed, and the $10,000 understatement remains intact as long as the land is held.

Straight-Line Method of Determining Depreciation

Question: If a company pays $600,000 on January 1, Year One to rent a building to serve as a store for five years, a prepaid rent account (an asset) is established for that amount. Because the rented facility is used to generate revenues throughout this period, a portion of the cost is reclassified annually as expense to comply with the matching principle. At the end of Year One, $120,000 (or one-fifth) of the cost is moved from the asset balance into rent expense by means of an adjusting entry. Prepaid rent shown on the balance sheet drops to $480,000, the amount paid for the four remaining years. The same adjustment is required for each of the subsequent years as the time passes.

If, instead, the company buys a building with an expected five-year lifeThe estimated lives of property and equipment will vary widely. For example, in notes to its financial statements as of January 31, 2011, and for the year then ended, Walmart disclosed that the expected lives of its buildings and improvements ranged from three years to forty. for $600,000, the accounting is quite similar. The initial cost is capitalized to reflect the future economic benefit. Once again, at the end of each year, a portion of this cost is assigned to expense to satisfy the matching principle. This expense is referred to as depreciation. It is the cost of a long-lived asset that is recorded as expense each period. Should the Year One depreciation that is recognized in connection with this building also be $120,000 (one-fifth of the total cost)? How is the annual amount of depreciation expense determined for reporting purposes?

Answer: Depreciation is based on a mathematically derived system that allocates the asset’s cost to expense over the expected years of use. It does not mirror the actual loss of value over that period. The specific amount of depreciation expense recorded each year for buildings, machinery, furniture, and the like is determined using four variables:

- The historical cost of the asset

- Its expected useful life

- Any residual (or salvage) value anticipated at the end of the expected useful life

- An allocation pattern

After total cost is computed, officials estimate the useful life based on company experience with similar assets or on other sources of information such as guidelines provided by the manufacturer.As mentioned previously, land does not have a finite life and is, therefore, not subjected to the recording of depreciation expense. In a similar fashion, officials arrive at the expected residual value—an estimate of the likely worth of the asset at the end of its useful life. Both life expectancy and residual value can be no more than guesses.

To illustrate, assume a building is purchased by a company on January 1, Year One, for cash of $600,000. Based on experience with similar properties, officials believe that this structure will be worth only $30,000 at the end of an expected five-year life. U.S. GAAP does not require any specific computational method for determining the annual allocation of the asset’s cost to expense. Over fifty years ago, the Committee on Accounting Procedure (the authoritative body at the time) issued Accounting Research Bulletin 43, which stated that any method could be used to determine annual depreciation if it provided an expense in a “systematic and rational manner.” This guidance remains in effect today.

Consequently, a vast majority of reporting companies (including Walmart) have chosen to adopt the straight-line method to assign the cost of property and equipment to expense over their useful lives. The estimated residual value is subtracted from cost to arrive at the asset’s depreciable base. This figure is then expensed evenly over the expected life. It is systematic and rational. Straight-line depreciationMethod used to calculate the annual amount of depreciation expense by subtracting any estimated residual value from cost and then dividing this depreciable base by the asset’s estimated useful life; a majority of companies in the United States use this method for financial reporting purposes. allocates an equal expense to each period in which the asset is used to generate revenue.

Straight-line method:

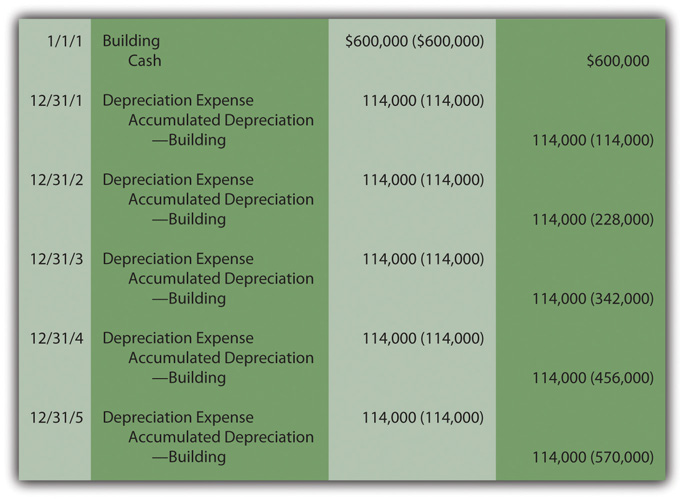

(cost – estimated residual value) = depreciable base depreciable base/expected useful life = annual depreciation ($600,000 – $30,000) = $570,000/5 years = depreciation expense of $114,000 per yearRecording Depreciation Expense

Question: An accountant determines depreciation for the current year based on the asset’s cost and estimated life and residual value. After depreciation has been calculated, how is this allocation of the asset’s cost to expense recorded within the company’s accounting system?

Answer: An adjusting entry is prepared at the end of each period to move the assigned cost from the asset account on the balance sheet to expense on the income statement. To reiterate, the building account is not directly reduced. A separate negative or contra account (accumulated depreciation) is created to reflect the total amount of the cost that has been expensed to date. Thus, the asset’s net book value as well as its original historical cost are both still in evidence.

The entries to record the cost of acquiring this building and the annual depreciation expense over the five-year life are shown in Figure 10.2 "Building Acquisition and Straight-Line Depreciation". The straight-line method is used here to determine each individual allocation to expense. Now that students are familiar with using debits and credits for recording, the number in parenthesis is included (where relevant to the discussion) to indicate the total account balance after the entry is posted. As has been indicated, revenues, expenses, and dividends are closed out each year. Thus, the depreciation expense reported on each income statement measures only the expense assigned to that period.

Figure 10.2 Building Acquisition and Straight-Line Depreciation

Because the straight-line method is applied, depreciation expense is a consistent $114,000 each year. As a result, the net book value reported on the balance sheet drops during the asset’s useful life from $600,000 to $30,000. At the end of the first year, it is $486,000 ($600,000 cost minus accumulated depreciation $114,000). At the end of the second year, net book value is reduced to $372,000 ($600,000 cost minus accumulated depreciation of $228,000). This pattern continues over the entire five years until the net book value equals the expected residual value of $30,000.

Test Yourself

Question:

On January 1, Year One, the Ramalda Corporation pays $600,000 for a piece of equipment that will produce widgets to be sold to the public. The company expects the asset to carry out this function for ten years and then be sold for $50,000. The straight-line method of depreciation is used. At the end of Year Two, company officials receive an offer to buy the equipment for $500,000. They reject this offer because they believe the asset is actually worth $525,000. What is the net reported balance for this equipment on the company’s balance sheet as of December 31, Year Two?

- $480,000

- $490,000

- $500,000

- $525,000

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $490,000.

Explanation:

Unless the value of property or equipment is impaired or the asset will be sold in the near future, fair value is ignored. Cost is the reporting basis. This equipment has a depreciable base of $550,000 ($600,000 cost less $50,000 residual value). The asset is expected to generate revenues for ten years. Annual depreciation is $55,000 ($550,000/ten years). After two years, net book value is $490,000 ($600,000 cost less $55,000 and $55,000 or accumulated depreciation of $110,000).

Key Takeaway

Tangible operating assets with lives of over a year are initially reported at historical cost. All expenditures are capitalized if they are normal and necessary to put the property into the position and condition to assist the owner in generating revenue. If the asset has a finite life, this cost is then assigned to expense over the years of expected use by means of a systematic and rational pattern. Many companies apply the straight-line method, which assigns an equal amount of expense to every full year of use. In that approach, the expected residual value is subtracted from cost to get the depreciable base. This figure is allocated evenly over the anticipated years of use by the company.