This is “Determining and Reporting the Cost of Inventory”, section 8.1 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.1 Determining and Reporting the Cost of Inventory

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Understand that inventory is recorded initially at historical cost.

- Provide the guiding rule for identifying expenditures that are capitalized in the acquisition of inventory.

- Explain the rationale for offering a discount for quick payments of cash as well as the accounting used to report such reductions.

The Reported Inventory Balance

Question: The asset section of the February 26, 2011, balance sheet produced by Best Buy Co. Inc. reports net accounts receivable of $2.348 billion. Based on coverage provided in the previous chapter, savvy decision makers should know that this figure reflects net realizable value—the estimation by officials of the cash amount that will be collected from the receivables owed to the company by its customers. Knowledge of financial accounting allows any individual to understand the information conveyed in a set of financial statements.

As is common, the next account that appears on Best Buy’s balance sheet is “merchandise inventories.” This asset includes all items held as of that date that were acquired for sales purposes—televisions, cameras, computers, and the like. The monetary figure disclosed by the company for this asset is $5.897 billion. Does this balance also indicate net realizable value—the cash expected to be generated from the company’s merchandise—or is different information reflected? On a balance sheet, what does the amount reported for inventory represent?

Answer: The challenge of analyzing the various assets reported by an organization would be reduced substantially if all account balances disclosed the same basic information, such as net realizable value. However, over the decades, virtually every asset has come to have its own individualized method of reporting, one created to address the special peculiarities of that account. Thus, the term “presented fairly” is often reflected in a totally different way for each asset. Reporting accounts receivables, for example, at net realizable value has no impact on the approach that is generally accepted for inventoryA current asset bought or manufactured for the purpose of selling in order to generate revenue..

Accounting for inventory is more complicated because reporting is not as standardized as with accounts receivable. For example, under certain circumstances, the balance sheet amount shown for inventory actually does reflect net realizable value. However, several other meanings for that balance are more likely. The range of accounting alternatives emphasizes the need for a careful reading of financial statement notes rather than fixating on a few reported numbers alone. Without study of the available disclosures, a decision maker simply cannot know what Best Buy means by the $5.897 billion figure reported for its inventory.

For all cases, though, the reporting of inventory begins with its cost. In contrast, cost is never an issue even considered in the reporting of accounts receivable.

Determining the Cost of Inventory

Question: Every item bought for sales purposes has a definite cost. The accounting process for inventory begins with a calculation of that cost. How does an accountant determine the cost of acquired inventory?

Answer: The financial reporting for inventory starts by identifying the cost paid to obtain the item. In acquiring inventory, officials make the considered decision to allocate a certain amount of their scarce resources. The amount of that sacrifice is interesting information. What did the company expend to obtain this merchandise? That is a reasonable question to ask since this information can be valuable to decision makers.

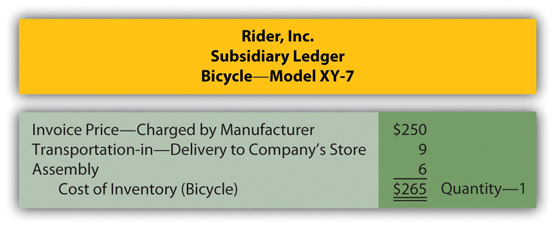

To illustrate, assume that a sporting goods company (Rider Inc.) acquires a new bicycle (Model XY-7) to sell. Rider’s accounting system should be designed to determine the cost of this piece of inventory, the price that the company willingly paid to obtain the asset. Assume that $250 was charged by the manufacturer (Builder Company) for the bicycle, and the purchase was made by Rider on credit. Rider spends $9 in cash to transport the item from the factory to one of its retail stores and another $6 to have the pieces assembled so that the bicycle can be displayed in the salesroom for customers to examine.

In accounting for the acquisition of inventory, cost is said to include all normal and necessary amounts incurred to get the item into condition and position to be sold. All such expenditures provide future value. Hence, as shown in Figure 8.1 "Monitoring the Cost of an Inventory Item—Subsidiary Ledger", by the time this bicycle has reached Rider’s retail location and been readied for sale, the cost to the sporting goods company is $265.

Figure 8.1 Monitoring the Cost of an Inventory Item—Subsidiary Ledger

Charges for delivering this merchandise and assembling the parts were included in the asset account (the traditional term for adding a cost to an asset account, capitalizationThe process of recording a cost as an asset rather than an expense; for inventory, it includes all normal and necessary costs associated with getting the asset into position and condition to be sold., was introduced previously). Both of these expenditures were properly viewed as normal and necessary to get the bicycle into condition and position to be sold. Interestingly, any amount later expended by the company to transport inventory from the store to a buying customer is recorded as an expense because that cost is incurred after the sale takes place. At that point, no further future value exists since the merchandise has already been sold.

Occasionally, costs arise where the “normal and necessary” standard may be difficult to apply. To illustrate, assume that the president of a store that sells antiques buys a 120-year-old table for resell purposes. When the table arrives at the store, another $300 must be spent to fix a scratch cut across its surface. Should this added cost be capitalized (added to the reported balance for inventory) or expensed? The answer to this question is not readily apparent and depends on ascertaining the relevant facts. Here are two possibilities.

Scenario one: The table was acquired by the president with the knowledge that the scratch already existed and needed to be fixed prior to offering the merchandise for sale. In that case, repair is a normal and necessary activity to bring the table into the condition necessary to be sold. The $300 is capitalized, recorded as an addition to the reported cost of the inventory.

Scenario two: The table was bought without the scratch but was damaged when first moved into the store through an act of employee carelessness. The table must be repaired, but the scratch was neither normal nor necessary. The cost could have been avoided. This $300 is not capitalized but rather reported as a repair expense by the store.

As discussed in an earlier chapter, if the accountant cannot make a reasonable determination as to whether a particular cost qualifies as normal and necessary, the practice of conservatism requires the $300 to be reported as an expense. When in doubt, the alternative that makes reported figures look best is avoided so that decision makers are not encouraged to be overly optimistic about the company’s financial health and future prospects.

Test Yourself

Question:

Near the end of Year One, the Morganton Hardware Company buys five lawn mowers for sale by paying $300 each. The delivery cost to transport these items to the store was another $40 in total. In January of the following year, $60 more was spent to assemble all the parts and then clean the finished products so they could be placed in the company’s showroom. On February 3, Year Two, one of these lawn mowers was sold for $500 cash. The company paid a final $25 to have this item delivered to the buyer. If no other transactions take place, what net income does the company recognize for Year Two?

- $150

- $155

- $160

- $175

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $155.

Explanation:

The cost of the mowers ($1,500 or $300 × 5) along with transportation cost ($40) and assembling and cleaning costs ($60) are normal and necessary to get the items into position and condition to be sold. Total capitalized cost is $1,600 or $320 per unit. Gross profit on the first sale is $180 ($500 less $320). The $25 delivery charge is expensed; it is not capitalized because it occurred after the sale and had no future value. Net income is $155 ($180 gross profit minus $25 delivery expense).

Offering Discounts for Quick Payment

Question: When inventory is sold, some sellers are willing to accept a reduced amount to encourage fast payment—an offer that is called a cash discount (or sales discount or purchases discount depending on whether the seller or the buyer is making the entry). Cash becomes available sooner so that the seller can quickly put it back into circulation to make more profits. In addition, the possibility that a receivable will become uncollectible is reduced if the balance due is not allowed to get too old. Tempting buyers to make quick payments to reduce their cost is viewed as a smart business practice by many sellers.

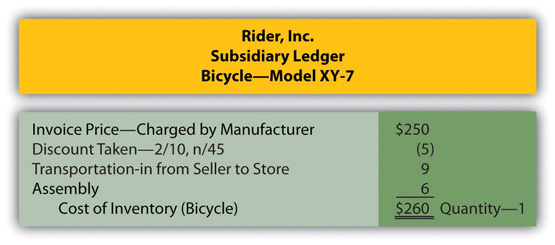

To illustrate, assume the invoice received by the sporting goods company (Rider) for the above bicycle indicates the proper $250 balance but also includes the notation: 2/10, n/45. What message is being conveyed by the seller? How do cash discounts impact the reporting of inventory?

Answer: Sellers—such as Builder Company in this example—can offer a wide variety of discount terms to encourage speedy payment. One such as 2/10, n/45 is generally read “two ten, net 45.” It informs the buyer that a 2 percent discount is available if the invoice is paid by the tenth day. The net amount that remains unpaid (after any merchandise returns or partial cash payments) is due on the forty-fifth day. Rider has the option to pay $245 for the bicycle within ten days of receiving the invoice by taking advantage of the $5 discount ($250 × 0.02). Or the sporting goods company can wait until the forty-fifth day but then is responsible for the entire $250. In practice, a variety of other discount terms are frequently encountered such as 1/10, n/30 or 2/10, n/30.

Many companies automatically take all cash discounts as a matter of policy because of the high rate of interest earned. If Rider does not submit the money after ten days, it must pay an extra $5 in order to hold onto $245 for an additional thirty-five days. This delay equates to a 2.04 percent interest rate over just that short period of time ($5/$245 = 2.04 percent [rounded]). There are over ten thirty-five-day periods in a year. Paying the extra $5 is the equivalent of an annual interest rate in excess of 21 percent.

365 days per year/35 days holding the money = 10.43 time periods per year 2.04% (for 35 days) × 10.43 time periods = 21.28% interest rate for a yearThat substantial rate of interest expense is avoided by making early payment, a decision chosen by most companies unless they are experiencing serious cash flow difficulties.

Assuming that Rider avails itself of the discount offer, the capitalized cost of the inventory is reduced to $260.

Figure 8.2 Cost of Inventory Reduced by Cash Discount—Subsidiary Ledger

Test Yourself

Question:

On March 1, a hardware store buys inventory for resale purposes at a cost of $300. The invoice is mailed on March 2, and the manufacturer offers cash terms of 3/10, n/30. Store officials choose to settle 60 percent of the invoice on March 10 and the remainder on March 30. What was the total amount paid for the inventory?

- $291.00

- $294.60

- $296.40

- $300.00

Answer:

The correct answer is choice b: $294.60.

Explanation:

Of the total amount charged, $180.00 (60 percent of $300.00) is settled in a timely fashion which allows the company to take a 3 percent discount or $5.40 ($180.00 × 3 percent). The company’s first payment was $174.60 ($180.00 minus $5.40). The remaining $120.00 is paid at the end of thirty days, after the discount period has passed. No additional discount is available. The cost of the inventory to the company is $294.60 ($174.60 plus $120.00).

Key Takeaway

Any discussion of the reporting of inventory begins with the calculation of cost, the amount spent to obtain the merchandise. For inventory, cost encompasses all payments that are considered normal and necessary to get the items into condition and possession to be sold. All other expenditures are expensed as incurred. Cash discounts (such as 2/10, n/30) are often offered to buyers to encourage quick payment. The seller wants to get its money as quickly as possible to plow back into operations. For the buyer, taking advantage of such discounts is usually a wise business decision because they effectively provide interest at a relatively high rate.