This is “T.S. Eliot (1888–1965)”, section 8.6 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.6 T.S. Eliot (1888–1965)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify elements of Modernism in T. S. Eliot’s poetry.

- Compare the imagery of Eliot’s poetry to the metaphysical conceits of John Donne or other metaphysical poets of the 17th century.

- Identify religious imagery in “East Coker” and determine its purpose.

- Determine what the choice of images reveals about the speaker’s character in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Anthologies of American literature as well as British literature contain T.S. Eliot’s work. Because Eliot is one of the great modernist poets, both countries are eager to claim him.

T.S. Eliot.

by Lady Ottoline Marrell 1934

Biography

T.S. Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri and attended Harvard University. After an additional year of education in Paris, he went to Oxford University and then back to Harvard. In 1914, he moved to and settled in England, marrying an English woman and working as a teacher and a banker. Here he met the American modernist poet Ezra Pound who encouraged Eliot’s writing. Eliot’s first publication, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” established him as an important modernist poet. Eliot began working at Faber and Faber publishing company, eventually becoming a director. He became a naturalized British citizen in 1927.

Chapter House at Canterbury Cathedral.

Eliot admired and helped foster a renewed interest in the 17th-century Metaphysical poets such as John Donne. Modernist poets appreciated their metaphysical conceits, striving to achieve hard images in their own writing, images that were clear and sharp due to precise, concise language.

Eliot also wrote verse dramas. Murder in the Cathedral recounts the martyrdom of Becket at Canterbury Cathedral in 1170. The work was first performed in the Chapter House at Canterbury Cathedral, only steps from where Becket’s murder took place.

In 1948, Eliot received the Nobel Prize for literature. He remarried later in life, and on his death in 1965, his second wife worked to compile and edit his papers and manuscript drafts of his work.

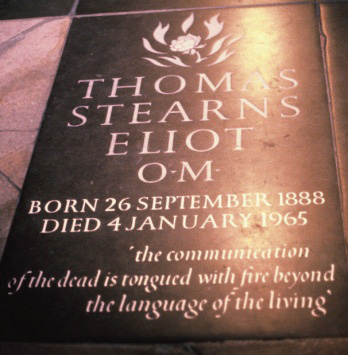

Eliot’s ashes are interred at East Coker Church, a small village in southwest England that was home to his ancestors.

He also is honored with a commemorative stone in Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey.

Texts

- Four Quartets. available through subscription database Chadwyck-Healey Literature Collection. Eliot, T. S. (Thomas Stearns), 1888–1965 [from Collected Poems 1909–1962 (1974)] , Faber and Faber.

- “Prufrock and Other Observations.” Project Gutenberg.

- “T.S. Eliot: The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1919).” Prof. Paul Brians, Washington State University.

- “The Waste Land.” Project Gutenberg.

“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Analyses of Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” often consist of as many questions as statements. The poem uses the modernist stream of consciousness technique, an effort to demonstrate the workings of the human mind. Knowing we are, in a sense, listening to an individual’s thoughts, leaves questions because we are not presented a consciously constructed narrative.

The title itself seems paradoxical with the pairing of the idea of a love song with a name as prosaic as J. Alfred Prufrock, a name Eliot suggested he may have remembered from the name of a furniture company in his native St. Louis.

The epigraph to “Prufrock” is from Dante’s Inferno. The epigraph’s speaker states that if his listener were returning to earth and therefore could repeat his story to others, he would not speak; however, since no one can return from Hell, he can speak his words. The epigraph leads readers of “Prufrock” to wonder if they are reading a dramatic monologue, in which the speaker addresses a specific listener, whether the readers are the auditors, or whether we are overhearing the workings of a human mind of which we ordinarily would not be aware. Are these words, like the epigraph speaker’s words, that are not meant to be heard by others?

This dilemma calls into question the reality of all the events of the poem. Is the speaker actually walking somewhere, or is he only rehearsing this possibility mentally? Is he imagining something that will happen, remembering something that has happened, or actually experiencing the event?

Brief Excerpts from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherised upon a table;

The first three lines of the poem provide the type of unusual, unexpected comparison reminiscent of metaphysical conceits. In this love song, with the picture of a couple walking in the evening, the scene is compared to a patient under sedation upon an operating table, hardly a romantic image. The meter also emphasizes the incongruity of the simile: the first two lines are regular in meter, but the smooth rhythm stumbles with line 3.

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create.…

In lines 26–28, the speaker talks of preparing a face to meet other faces, of assuming a mask, a façade, to meet other people who are just as artificial, as counterfeit, as the speaker.

The references to the taking of toast and tea in a room where “women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo” suggest that the speaker is on his way to an afternoon tea attended by insincere people talking about topics intended to impress others. Here, too, however, we are left with the uncertainly of whether we are experiencing the events as the speaker does or whether the speaker is recalling or anticipating the occurrence.

The speaker imagines the crowd whispering about his inadequacies from his bald spot to his thinness until he feels like a bug specimen pinned under a scientist’s microscope. And all the time he wonders if he dares to “disturb the universe” by breaking out of the pattern of expected behavior.

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

In lines 73 and 74, the speaker states he should have been a pair of claws, a crab, on the floor of the sea, silent and far away from the world, from the critical eyes, living strictly by instinct with none of the angst resulting from his current situation.

Lines 75 through 110 present the speaker wondering how things might have been, or might be in the future, different if he had the courage to force the moment from the triviality of everyday life to the important questions. At the same time, he knows he did not, or will not, have the courage to speak his convictions or to pronounce the ideas which are important to him. The following lines provide the reason:

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

He is too afraid to step out from behind the mask he prepared, the face he shows the world, the façade of conformity that makes him act like the rest of society safely behind their masks. The meaningless ritual in which he and those around him indulge characterizes the modernist view of life. Having realized that he will never address the important questions, the speaker rationalizes his behavior with the thought that in life’s drama he does not play a leading part, such as Hamlet, but only a bit part.

With the realization that he will never address the important issues of life, the speaker begins to imagine the rest of his life, sinking into an ever-more-powerless old age. The speaker claims in lines 124–126 he has heard mermaids singing.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves.…

In British folklore, mermaids are often evil omens, sirens luring sailors to their deaths. In this context, the mermaids seem to represent something beautiful denied to the speaker. On the other hand, the following lines picture the speaker at the bottom of the sea with the mermaids, again, as when he pictures himself as a crab, isolated from human contact. The sound of human voices drowns him.

Whatever the specifics of Prufrock’s situation, the despair, the inability to shape his own circumstances, the lack of free will to make his desires reality all reflect the modernism of the early 20th century.

The Modern American Poetry website from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign provides a summary of seminal commentary on “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Four Quartets: “East Coker”

Eliot wrote what would become the first of the Four Quartets, “Burnt Norton” and published it separately from the other three poems in a poetry collection in 1936. The other three poems, “East Coker,” “The Dry Salvages,” and East Giddings” were written during World War II, but the four were not published as a whole until 1943.

In music, a quartet consists of four different voices, the title thus suggesting multiple voices in each poem, each quartet. Although the more typical form for musical quartets, particularly string quartets, is four movements, notably Haydn’s quartets and Beethoven’s later quartets often have five movements. Each of Eliot’s poems consists of five parts.

The Four Quartets are often interpreted as representing the medieval idea of the fours elements: air, earth, water, and fire.

The connecting theme of the Four Quartets is time, specifically the continuity of time and eternity and the role of human life and death in this continuity. Eliot conveys this theme through religious imagery. In “East Coker” humans are offered a chance to glimpse an ancient time, still present for those willing to see the continuity of life through eternity.

Key Takeaways

- Eliot’s poetry uses stream of consciousness techniques rather than clearly chronological narratives.

- Eliot revived interest in the metaphysical poetry of the 17th century because he valued its unusual and concrete images.

- Religious imagery provides familiar allusions for readers but in an unorthodox context and meaning.

Exercises

“East Coker”

- Interpret the first line: “In my beginning is my end.”

- In the first stanza, does the speaker refer to literal houses, or are the houses symbolic?

- What depth of meaning is added to the poem by using lines which echo the biblical book of Ecclesiastes?

- What is the significance of the scene in the third stanza of Part I?

- Summarize the themes of time and of writing poetry in Parts II and III.

- What might be the purpose of the change in verse form in Part IV?

- What might the Good Friday imagery have suggested to Eliot’s contemporary audience?

- Examine the function of age in Part V.

- Interpret the last line: “In my end is my beginning.”

“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

- In the first 35 lines, what descriptive details combine to form a picture of a less-than-pleasant environment? What does this particular environment suggest about the speaker?

- In line 28, what is being “murder[ed] and creat[ed]”?

- Why does the speaker imagine his life being measured out in “coffee spoons”?

- Who is the “eternal Footman” referred to in line 85?

- Identify the religious allusions in lines 75 through 110. What is the purpose of using religious allusions?

- What lines depict the speaker growing old?

- What do you suppose the mermaids represent?

Resources

General Information

- T.S. Eliot (1888–1965). Modern American Poetry. Ed. Jed Esty, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- “T.S. Eliot, The Art of Poetry No. 1.” The Paris Review. Spring–Summer 1959. Donald Hall interviews T.S. Eliot.

Biography

- “Biography.” The Nobel Prize in Literature 1948. T.S. Eliot. Nobelprize.org. The Official Web Site of the Nobel Prize.

- T.S. Eliot. Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

- “T.S. Eliot 1888–1965.” The Poetry Foundation.

- “T.S. Eliot: Biographical Timeline.” Modern American Poetry. Jed Esty, ed., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- “T.S. Eliot’s Life and Career.” Ronald Bush. Modern American Poetry. Jed Esty, ed., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Text

- Four Quartets. available through subscription database Chadwyck-Healey Literature Collection. Eliot, T. S. (Thomas Stearns), 1888–1965 [from Collected Poems 1909–1962 (1974)] , Faber and Faber.

- “Prufrock and Other Observations.” Project Gutenberg.

- “T.S. Eliot: The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1919).” Prof. Paul Brians, Washington State University.

- “The Waste Land.” Project Gutenberg.

Audio

- T.S. Eliot. “The Waste Land.” HarperAudio! HarperCollins Publishers. T.S. Eliot reading sections of “The Waste Land.”

- “T.S. Eliot.” The Poetry Archives. T. S. Eliot reading “Journey of the Magi.” recordings of “Extract from Four Quartets” and “The Waste Land.”

- “The Wasteland.” Project Gutenberg.

Video

- “Our Life in Poetry: T.S. Eliot’s ‘Four Quartets.’” The Philoctetes Center for the Multidisciplinary Study of the Imagination. New York Council for the Humanities.

- “T.S. Eliot.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.