This is “The War Poets”, section 8.4 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.4 The War Poets

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the effects of World War I on Britain and on the development of Modern literature.

- Recognize the cognitive dissonance caused by accounts of the achievements and victories of the British military and the firsthand accounts of returning individuals and of writers such as the war poets.

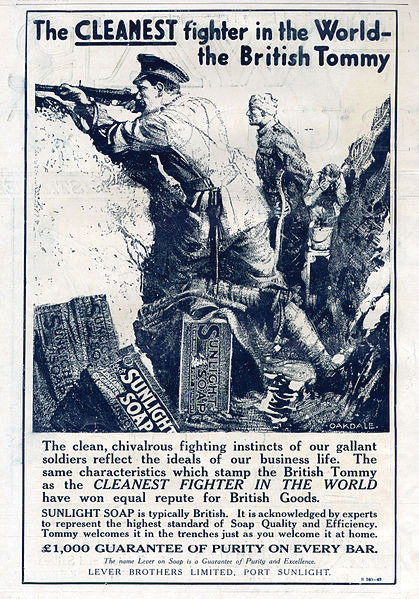

No words could describe the general public’s perception of World War I better than the photo essay at the Modern American Poetry website (Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). In the photo essay note the first pictures of men going off to war, women cheering them on, both sides confident in their abilities and confident that the war would be over within a few months followed by increasingly somber pictures of the reality. The ad pictured here capitalized on the widespread belief that British troops, because they were honorable, chivalrous, gallant, would soon march home in victory. The work of soldier poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Rupert Brooke informed the British public of the realities of war as much as, perhaps more than, the censored journalistic reports that reached British newspapers and magazines. The brutalities of outdated military tactics used against modern weapons resulted in incomparable British losses. The war poets painted vivid pictures of the realities of war.

The BBC provides extensive information about World War I, including virtual tours of the trenches and excerpts from oral histories, diaries, and letters.

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

Wilfred Owen was born in Shropshire, a rural area of England. He was interested in poetry, particularly Keats and other Romantic poets, and wrote poetry in his teens. When he failed to be admitted to college, he moved to France to work as an English language tutor. After World War I began, he moved back to England to enlist. In 1917, he was diagnosed with what was then called shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital in Scotland for treatment. There he met Siegfried Sassoon. Both poets wrote some of their most well-known poetry while there. Owen returned to the front in the fall of 1918, won the Military Cross, and just days before the war ended was killed in battle. His family received the news of his death in the midst of celebrations on November 11, Armistice Day, 1918.

“Dulce et Decorum Est”

The Latin phrase from a work by Homer may be translated “It is sweet and right to die for one’s country.” Juxtaposed against the illusion of war as a glorious adventure, Owen paints the horrors of war’s reality.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

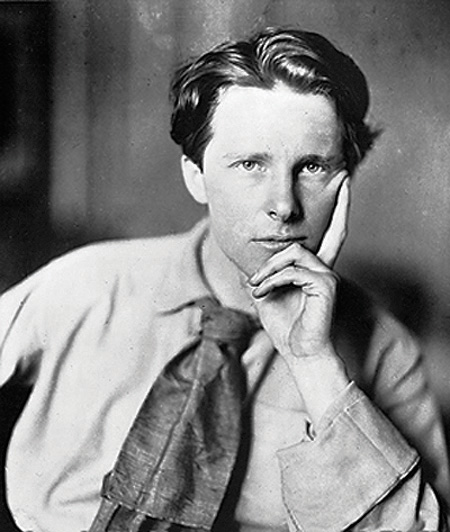

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

Rupert Brooke also was fond of the works of the Romantic poets. He attended Cambridge University where he met and befriended members of the Bloomsbury Group whose literature was an important piece of British modernism. Brooke was commissioned into the Royal Navy, but in 1915 he died of sepsis onboard a hospital ship. He is buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

Rupert Brooke’s grave.

“The Soldier”

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

Although Sassoon grew up in a family divided by religious differences, his father was Jewish, his mother Roman Catholic, his background provided him enough wealth to live comfortably. He attended Cambridge University for a while, without taking a degree, preferring to live the life of a country gentlemen playing cricket and writing. Sassoon joined the British Army at the beginning of World War I; he was sent home from the front twice, once when he contracted a fever and once for shell shock, this being the occasion when he met Wilfred Owen. Sassoon survived World War I and continued writing until his death.

By George Charles Beresford, 1915

“Glory of Women”

Glory of Women

You love us when we’re heroes, home on leave,

Or wounded in a mentionable place.

You worship decorations; you believe

That chivalry redeems the war’s disgrace.

You make us shells. You listen with delight,

By tales of dirt and danger fondly thrilled.

You crown our distant ardours while we fight,

And mourn our laurelled memories when we’re killed.

You can’t believe that British troops “retire”

When hell’s last horror breaks them, and they run,

Trampling the terrible corpses—blind with blood.

_O German mother dreaming by the fire,

While you are knitting socks to send your son

His face is trodden deeper in the mud._

In the last three lines, the speaker turns from addressing the people back home in England to speak to the imagined mother of a German soldier. His comment has the effect of humanizing the political enemy.

Key Takeaways

- The staggering casualties and the horrors of modern warfare contributed to the modernist sense that the world lacks a stable, centralizing force and that life lacks ultimate purpose—that the world we live in is, in the words of Thomas Hardy’s character Tess, a “blighted one.”

- The work of the war poets helped enlighten the public about the nature of the war experience.

Exercises

- In “Dulce Et Decorum Est” the last stanza is directed to people back at home. What is the purpose of this stanza?

- Read this brief description of the mustard gas used in World War I. Does Owen’s description seem realistic? Which account seems more emotionally based? Which might have had a more profound effect on the people at home away from the war?

- Brooke’s poem “The Soldier” seems brighter in mood and tone than the other two poems, and yet it describes a soldier’s death. What makes the poem less horrific than “Dulce Et Decorum Est”?

- How would you describe the mood of the speaker in “The Soldier”?

- The speaker of “Glory of Women” expresses disillusionment with the supposed glory of war. How would you describe his attitude toward the women back at home?

- In “Glory of Women,” although the Germans are the enemy of the British, what common human trait does the poet reveal?

Resources

General Information

- Anthem for Doomed Youth: Writers and Literature of The Great War, 1914–1918. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- The First World War Poetry Digital Archive. University of Oxford and JISC [Joint Information Systems Committee]. text (including biographies, primary texts, background information), images (including portraits, digital images of manuscripts, photos of World War I, images from the Imperial War Museum); audio; video (including a Second Life Virtual Simulation from the Imperial War Museum and a YouTube video introduction, over 150 video clips, film clips), and an interactive timeline.

- “Home Front: World War One.” British History. BBC.

- “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est.’” Online Gallery. British Library. image of handwritten manuscript and information about Owen and World War I.

- “World War One.” World Wars. BBC History.

Biography

- Poems by Wilfred Owen with an Introduction by Siegfried Sassoon. A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Pennsylvania State University.

- “Rupert Brooke, 1887–1915.” “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Rupert Brooke (1887–1915).” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Rupert Chawner Brooke.” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “Siegfried Sassoon.” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967).” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Wilfred Owen (1893–1918).” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Wilfred Owen (1893–1918).” “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Wilfred Edward Salter Owen.” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Texts

- “1914 V. The Soldier“ by Rupert Brooke. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Anthem for Doomed Youth.” by Wilfred Owen. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. text and a digital image of the original handwritten manuscript.

- “Dulce et Decorum Est.” by Wilfred Owen. Paul Halsall, Fordham University. Internet Modern History Sourcebook.

- “Dulce et Decorum Est.” by Wilfred Owen. “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Glory of Women.” by Siegfred Sassoon. Counter-Attack and Other Poems. 1918. Bartleby.com.

- “Glory of Women.” The War Poems of Siegfried Sassoon. Project Gutenberg.

- “Sonnet V. The Soldier.” by Rupert Brooke. “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

Images

- “Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est.’” Online Gallery. British Library.

- “World War I Photo Essay.” Modern American Poetry. Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Audio

- “Dulce et Decorum Est.” by Wilfred Owen. LibriVox.

- Extract from a letter by Wilfred Owen, July 1918. “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Siegfried Sassoon 1886–1967). A Recording Owned by Mrs. Olga Ironside Wood. 1 January 1967. BBC.

- “The Soldier.” by Rupert Brooke. LibriVox.

- “Wilfred Owen Audio Gallery.” Dominic Hibberd. World Wars. BBC History.