This is “Thomas Hardy (1840–1928)”, section 8.2 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

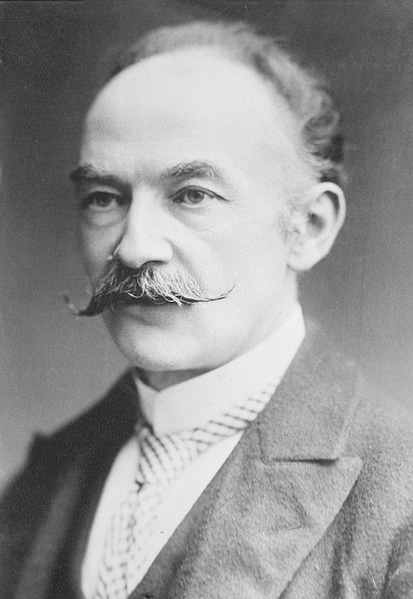

8.2 Thomas Hardy (1840–1928)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Characterize the beginning of the 20th century as depicted in Thomas Hardy’s poetry.

- Identify elements of modernism in the poetry of Thomas Hardy.

- Evaluate the effect of “Drummer Hodge” in early 20th-century discourse on imperialism.

- Assess the opinion of traditional religion expressed in “Hap,” “The Impercipient,” and “The Darkling Thrush” and compare/contrast that expression with other works from the Victorian Era and the early 20th century.

Biography

Texts

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Dead Drummer [Drummer Hodge].” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “Drummer Hodge or The Dead Drummer.” The Victorian Web.

- “Hap.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Hap.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. 1898. Bartleby.com.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

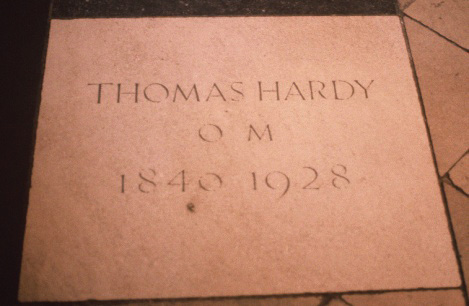

Hardy’s memorial stone in Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey.

“Hap”

Although Hardy repudiated the claim, he was labeled “The Great Pessimist.” Hardy, instead, described himself as a melioristA person who believes the world and individuals have the potential for improvement., a person who believes the world and individuals have the potential for improvement. Nonetheless, the pessimistic tone of modernism permeates his work.

If but some vengeful god would call to me

From up the sky, and laugh: “Thou suffering thing,

Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy,

That thy love’s loss is my hate’s profiting!”

Then would I bear, and clench myself, and die,

Steeled by the sense of ire unmerited;

Half-eased, too, that a Powerfuller than I

Had willed and meted me the tears I shed.

But not so. How arrives it joy lies slain,

And why unblooms the best hope ever sown?

—Crass Casualty obstructs the sun and rain,

And dicing Time for gladness casts a moan….

These purblind Doomsters had as readily strown

Blisses about my pilgrimage as pain.

In modernism, the proper response to fate beyond individual control is stoicism—an endurance of the pain and heartache of life with dignity and without complaint. Such stoicism is evident in Hardy’s poem “Hap.”

In “Hap” the title gives an important clue about the poem’s content: the word hap means chance.

The first two stanzas of the poem are just one sentence. It is important to note that the entire first stanza is an “if” clause. The speaker is not saying, “There is a vengeful god”; he is saying “If there were a vengeful god.” If there were a vengeful god that laughed at him, saying that his suffering provided pleasure for the vengeful god, then he would react as he describes in stanza 2.

If there were a vengeful god, then he would bear the suffering stoically, halfway finding comfort in the fact that at least there was some reason for his pain, at least some god was directing what happened to him.

Note the first short sentence of stanza 3: “But not so.” The monosyllabic words, each accented, emphasize the speaker’s conclusion. The “if” clause he proposes in stanza 1 is not so; in other words, there is no god, not even a vengeful one. This conclusion leads the speaker to ask why, then, he suffers in life—why are his hopes unfulfilled and his happiness ruined? The last four lines provide the answer to his question: it is simply chance. He personifies time, picturing Time rolling dice to see what will happen to him. It may be something good, or it may be something bad. Either way it’s simply a roll of the dice, a matter of “chance.”

“The Impercipient”

As in “Hap,” the title “The Impercipient” provides an important clue about the poem’s content. The word impercipient is from the same Latin root word as the words perceive and perceptive. The prefix “im” means not. Therefore, this poem is about a person who does not perceive or understand.

The Impercipient (at a Cathedral Service)

That from this bright believing band

An outcast I should be,

That faiths by which my comrades stand

Seem fantasies to me,

And mirage-mists their Shining Land,

Is a drear destiny.

Why thus my soul should be consigned

To infelicity,

Why always I must feel as blind

To sights my brethren see,

Why joys they’ve found I cannot find,

Abides a mystery.

Since heart of mine knows not that ease

Which they know; since it be

That He who breathes All’s Well to these

Breathes no All’s Well to me,

My lack might move their sympathies

And Christian charity!

I am like a gazer who should mark

An inland company

Standing upfingered, with, “Hark! hark!

The glorious distant sea!”

And feel, “Alas, ‘tis but yon dark

And wind-swept pine to me!”

Yet I would bear my shortcomings

With meet tranquillity,

But for the charge that blessed things

I’d liefer have unbe [not be].

O, doth a bird deprived of wings

Go earth-bound wilfully!

…

Enough. As yet disquiet clings

About us. Rest shall we.

“The Darkling Thrush”

“The Darkling Thrush,” written at the beginning of a new century, is a statement of sharp contrast to the philosophy of the Romantic Period, one hundred years before this poem was written. Hardy dated the poem 31 December 1900, the eve of the new century.

Cottage where Hardy was born.

The Darkling Thrush

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

The speaker recounts leaning on a gate leading into a coppice, a small wooded area, on a gray, frosty day. The world appears drab and dark (the “weakening eye of day” referring to the sun’s inability to penetrate the gloom). No people are out enjoying nature, as is often portrayed in Romantic poetry; they have all sought the warmth of human companionship around their household fires. The entire first stanza sets the stage with images of death.

In the midst of this description, Hardy draws attention to the bare, tangled branches, comparing them with the strings of a broken lyre. His image is chosen purposefully. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s image of the eolian harp (lyre) is one of the central images of Romantic poetry. “The Eolian Harp” was first printed in 1796, just over one hundred years earlier. The eolian harp symbolizes Romantic mysticism, a spiritual presence in the world (Coleridge’s “one Life, within us and abroad”) moving through nature, including human beings. Hardy says the eolian harp is now broken; that image no longer works. His universe is not spirit-filled, but lifeless and dried up. The land itself looks like a corpse.

Suddenly, in the midst of the frozen, dead world, the speaker hears the joyful song of a thrush, not a beautiful, vibrant bird like Shelley’s skylark, but a “frail, gaunt, and small” bird, worn out by storms.

In the final stanza, the speaker notes that the scene around the bird is bleak, certainly nothing to sing about, which leads him to state:

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

For over one hundred years, critics have disagreed about how to interpret these last four lines. There are two possibilities and scholars who support each side.

Possibility 1: There is some “Hope” in the world. Things aren’t as bleak as they seem. The bird is aware of a reason for hope, even if the speaker is not.

Possibility 2: The last two lines should be interpreted, “The bird may think there’s a reason for hope, but I, the speaker, surely don’t know what it is.”

The title of the poem could be seen as supporting either interpretation. The word darkling means “in the dark.” That phrase, however, could be interpreted literally (the bird is singing on a dark, cloudy day—”in the dark”) or figuratively (the bird is clueless—”in the dark”—the bird doesn’t know what’s going on, how bleak the world really is).

“The Ruined Maid”

Hardy’s audience would have recognized the expression ruined maid although we no longer use the phrase. They would have known immediately that the poem is about an unmarried woman who has lost her virginity. “The Ruined Maid” is, in fact, about two women: one who is “ruined” in a moral sense and another who, though chaste, is living a life of hardship and poverty.

The dialogue of the two women soon reveals that Melia, the ruined maid, is living in town, wearing beautiful clothes and jewelry, living a life of ease. The country woman, though virtuous, wears tattered clothes, digs potatoes to eke out a living, and envies ‘Melia. In the last two lines of the poem, ‘Melia tells her friend that she can’t expect a life of ease; she isn’t “ruined.”

The poem is humorous in effect, but it makes a serious point. Hardy leads the audience to ask themselves about society’s values and the way society works. Isn’t something wrong when virtue leads to poverty and “being ruined” leads to prosperity?

The Ruined Maid

“O ‘Melia, my dear, this does everything crown!

Who could have supposed I should meet you in Town?

And whence such fair garments, such prosperity?”—

“O didn’t you know I’d been ruined?” said she.

“You left us in tatters, without shoes or socks,

Tired of digging potatoes, and spudding up docks;

And now you’ve gay bracelets and bright feathers three!”—

“Yes: that’s how we dress when we’re ruined,” said she.

—”At home in the barton you said `thee’ and `thou,’

And `thik oon,’ and `theäs oon,’ and `t’other’; but now

Your talking quite fits ‘ee for high company!”—

“Some polish is gained with one’s ruin,” said she.

—”Your hands were like paws then, your face blue and bleak

But now I’m bewitched by your delicate cheek,

And your little gloves fit as on any lady!”—

“We never do work when we’re ruined,” said she.

—”You used to call home-life a hag-ridden dream,

And you’d sigh, and you’d sock; but at present you seem

To know not of megrims or melancholy!”—

“True. One’s pretty lively when ruined,” said she.

—”I wish I had feathers, a fine sweeping gown,

And a delicate face, and could strut about Town!”—

“My dear—a raw country girl, such as you be,

Cannot quite expect that. You ain’t ruined,” said she.

“Drummer Hodge”

Before and after the turn of the century the British were involved the Boer Wars. In a portion of what is now the Republic of South Africa, Dutch farmers settled and farmed peacefully throughout much of the 19th century. The native African people had already been defeated and driven off their land by European settlers. When gold and diamonds were discovered, the British were no longer content to let the Dutch settlers rule the area, and the struggle for control of the region and its riches grew into a horrific armed conflict.

The British set up concentration camps (the first time in history this term had been used) to imprison women and children of the Boer farmers who continued to fight. Loss of life among the British, the Boer fighters, and the innocent families was staggering. Hardy personalizes the loss of life by introducing his readers to one individual. In “Drummer Hodge,” originally titled “The Dead Drummer,” Hardy laments a young boy sent for the first time away from home to fight and die in a land he knew nothing about for a cause that mattered little if at all to him.

Drummer Hodge

I

They throw in Drummer Hodge, to rest

Uncoffined,—just as found:

His landmark is a kopje-crest

That breaks the veldt around;

And foreign constellations west

Each night above his mound.

II

Young Hodge the Drummer never knew—

Fresh from his Wessex home—

The meaning of the broad Karoo,

The Bush, the dusty loam,

And why uprose to nightly view

Strange stars amid the gloam.

III

Yet portion of that unknown plain

Will Hodge for ever be;

His homely Northern breast and brain

Grow to some Southern tree,

And strange-eyed constellations reign

His stars eternally.

Key Takeaways

- Bridging the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, Thomas Hardy’s poetry addresses questions that plagued Victorian society, such as imperialism, religion, traditional values, with a perspective that moves toward modernism’s view of the world as having no centering, stabilizing core.

- “Drummer Hodge” presents imperialism from an individual point of view, that of a boy sacrificed for reasons beyond his understanding.

- “Hap,” “The Impercipient,” and “The Darkling Thrush” depict a modern view of the world as lacking a transcendent spiritual power and therefore at the mercy of fate.

- “The Ruined Maid” describes two young women who illustrate the failure of traditional societal values.

Exercises

“The Impercipient”

- Where is the speaker of “The Impercipient”?

- Who is the “bright believing band” the speaker refers to in line 1?

- Identify what the speaker refers to in the phrases “fantasies,” “mirage-mists,” and “Shining Land” in stanza 1.

- In stanza 2, we learn what it is that the speaker does not perceive. What is it he does not understand?

- The capitalized “He” in stanza 3 presumably refers to God. Does the speaker blame God for his lack of perception?

- Explain the metaphor employed in stanza 4.

- In stanza 5 the speaker claims that he could bear his lack of perception calmly, stoically as it were, except for one “charge,” one accusation. What is that accusation?

- The speaker answers this charge in the abbreviated stanza 6 with another metaphor. To what does he compare himself? How does this metaphor relate to the accusation?

- Does the speaker reach a resolution to his lack of perception? How does the poem conclude?

“The Darkling Thrush”

- Compare the descriptive details of nature in “The Darkling Thrush” with the descriptions found in Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, or Keats.

- Account for Hardy’s choice of the words “spectre” and “haunted” in stanza 1.

- What is the purpose of describing the thrush as “frail, gaunt, and small” and “blast-beruffled”?

- Look up the various meaning of the word darkling in the Oxford English Dictionary. Particularly note any definitions and quotations from around the same time period Hardy was writing. Do the definitions affect your interpretation of the last stanza of the poem?

- How do you interpret the last stanza?

“Drummer Hodge”

- What is the effect of describing Drummer Hodge as being tossed into a grave with no coffin?

- What is the purpose of naming features such as the kopje and the veldt that are unfamiliar to Hodge?

- Why does Hardy refer to the stars in the final stanza?

Resources

General Information

- “Thomas Hardy 1840–1928.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Thomas Hardy’s Poetry—Study Guide.” Andrew Moore. www.universalteacher.org.uk.

- “Turning the Century With Thomas Hardy.” Dr. James K. Chandler, University of Chicago. Fathom Archive. The University of Chicago Archive Digital Collections.

Biography

- “A Chronology of the Life and Works of Thomas Hardy.” The Victorian Web. Philip V. Allingham, Lakehead University.

- “Thomas Hardy.” Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

- “Thomas Hardy.” Dr. John P. Farrell, University of Texas. Studies of Victorian Literature.

- “Thomas Hardy: A Biographical Sketch.” Dr. Andrzej Diniejko, Warsaw University.

Texts

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Dead Drummer [Drummer Hodge].” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “Drummer Hodge or The Dead Drummer.” The Victorian Web.

- “Hap.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Hap.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. 1898. Bartleby.com.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

Audio

- “The Darkling Thrush.” LibriVox.

- “The Darkling Thrush: Hardy’s Timely Meditation on the Turning of an Era.” Slate 30 Dec. 2008. Poet Robert Pinsky’s comments and reading of the poem.

- “Drummer Hodge (The Dead Drummer).” LibriVox.

- “Hap.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Ruined Maid.” LibriVox.

Video

- “Peggy Ashcroft Reading Thomas Hardy.” (“The Ruined Maid”). AthenaLearning. YouTube.

- “Thomas Hardy.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

Images

- Thomas Hardy and His Wessex.

- “Thomas Hardy’s Dorset.” Literary Landscapes. British Library.

Concordance

- A Hyper-Concordance to the Works of Thomas Hardy. The Victorian Literary Studies Archive. Mitsu Matsuoka, Nagoya University.