This is “Charles Dickens (1812–1870)”, section 7.2 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.2 Charles Dickens (1812–1870)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize A Tale of Two Cities as a serial novel, and account for the popularity of serial novels in Victorian England.

- Evaluate the role of the novel’s structure in conveying themes.

- Define and illustrate the use of literary devices such as anaphora, asyndeton, parallelism, and paradox in the novel’s famous opening lines.

- Distinguish developing characters from static characters and analyze the purpose of each.

- List and provide specific examples from the text of significant themes and images.

Biography

Dickens’s birthplace in Portsmouth.

Charles Dickens was born in 1812 in Portsmouth, a major port city in England. Although Dickens’s father worked as a clerk in a Navy office, he accrued debt and was imprisoned in Marshalsea Prison in London. Dickens’s mother and siblings joined him in prison, but at age twelve, Dickens went to work in a boot blacking factory in London to help support his family. The experiences he had there provided material for many of his novels that depict the working poor of London.

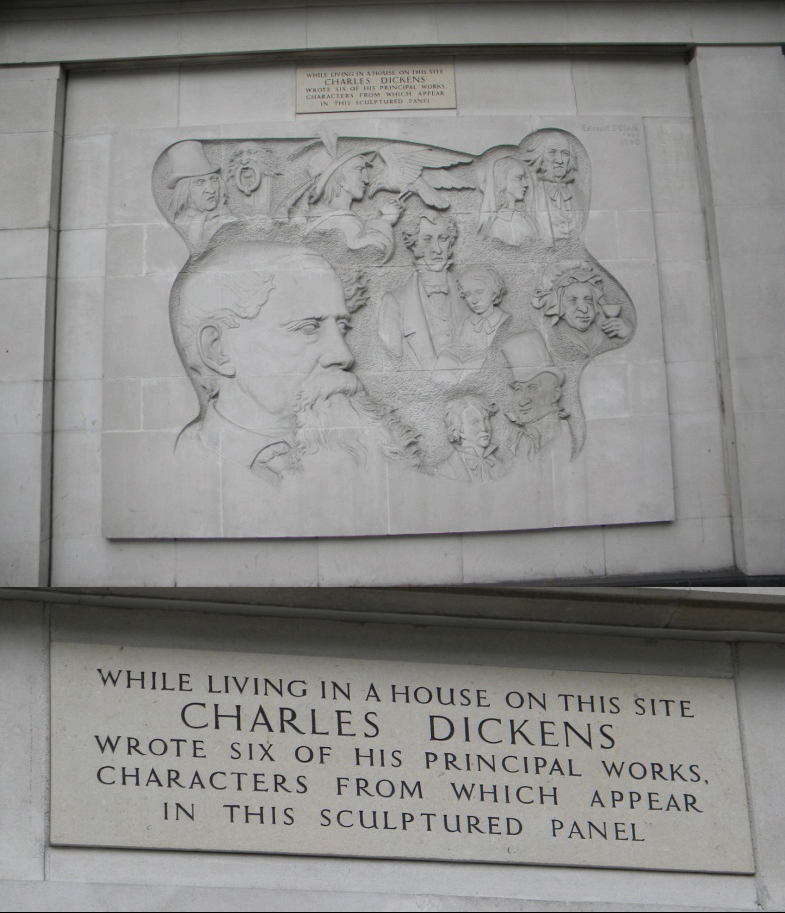

Forty-eight Doughty Street, the only surviving London house Dickens lived in. He was living here when he wrote Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby.

When his father was released from prison, Dickens was able to attend school and eventually worked as an office assistant for an attorney, a position which led to his becoming a court reporter, a reporter in Parliament, and eventually a journalist. With the success of his first serialized novel, Pickwick Papers, Dickens became a full-time novelist. His novels quickly achieved mass popularity, audiences eagerly awaiting new installments of the serial novels. Always interested in the theatre, Dickens conducted a series of public readings of his novels, drawing large enthusiastic audiences in England, on the continent, and in America. The readings added to his fame but later in life proved harmful to his health. Against his doctor’s advice, he completed a final reading tour in America and several more readings in England until he died of a stroke in 1870. Not surprisingly for a writer of his prominence, he was buried in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey.

Text

- Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870. A Tale of Two Cities. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Project Gutenberg.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. A. L. Burt Company, Publishers, New York. 1890. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

A Tale of Two Cities

Background

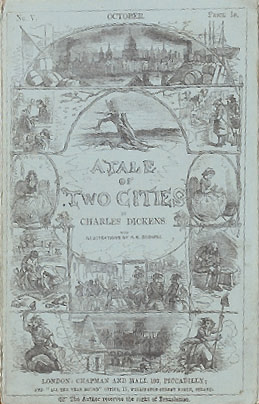

Published in 1859, A Tale of Two Cities is an example of a serial novel, a novel published in installments over a period of time. The novel was first published in weekly installments and again later in monthly installments.

Cover of the serial volume of A Tale of Two Cities with artwork by Hablot Knight Browne, known as Phiz, who illustrated many of Dickens’s works.

Fears that England might be heading toward a revolution like the French Revolution persisted into the Victorian Era. Literary references to these fears appear in many 19th-century works including Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest; Barrett Browning’s “The Cry of the Children,” Shelley’s “Men of England,” and Byron’s Don Juan.

The passage of Reform Bills in 1832, 1867, and 1884 to extend voting rights evidences the discontent of the previously disenfranchised working class and the unease of the upper classes who feared open rebellion.

Structure

A Tale of Two Cities is divided into three sections:

- Book the First: Recalled to Life (1775)

- Book the Second: The Golden Thread (1780–1789)

- Book the Third: The Track of a Storm (1792–1793)

Setting

“Chapter 1 The Period” begins with these well-known lines:

It was the best of times,

it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief,

it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light,

it was the season of Darkness,

it was the spring of hope,

it was the winter of despair…

Although these lines do little to depict the actual setting, they provide a hint of the contrasts the novel develops, contrasts of normal life and the Reign of Terror, innocence and guilt, life and death. Dickens makes the lines poetic and memorable with the use of literary devices:

- AnaphoraLines which begin with the same word or phrase.. Lines which begin with the same word or phrase (it was, it was, it was…)

- AsyndetonDeletion of conjunctions between sentences or clauses.. Deletion of conjunctions between sentences or clauses

- ParallelismThe use of the same grammatical structure for ideas of equal importance.. The use of the same grammatical structure for ideas of equal importance

- ParadoxThe juxtaposition of seemingly contradictory ideas.. The juxtaposition of seemingly contradictory ideas

To introduce the period in which the novel is set, Chapter 1 moves from these lines to more specific paragraphs which establish the places (Paris and London), the time (1775), and the atmosphere (foreboding). The last lines of Chapter 1 refer to the road of destiny and provide a transition to a literal road: the mail on the road to Dover. And thus the story begins.

Characters

- Sydney Carton. Carton is described as virtually dead, “like one who died young.” He may be seen as a Byronic hero, a dark, brooding anti-hero, aware of the profligate path in life he chooses. However, he is also a redemptive figure connected to resurrection imagery—life through death—and to prophecy.

- Charles Darnay. Unlike Carton and Dr. Manette, Darnay is a static character, exemplifying the Victorian ideal of the nature of nobility—he is nobly born and chooses to act nobly.

- Dr. Manette. Dr. Manette is the most vivid example of the theme of resurrection and redemption, particularly the redeeming capacity of love. Readers learn that Dr. Manette had been a man of strength and character but has been driven to madness by the evils he endures in France. Rescued and brought to England, a place of safety and sanity, he recovers because of Lucie’s loving care and is transformed into a strong, decisive character capable of planning and implementing a daring rescue.

- Lucie. The name Lucie is from the Latin root lux, meaning light, and her character exudes goodness, symbolized by light. She occupies one end of the good-evil spectrum. Like Darnay, Lucie is a static, flat character, a stereotypical Victorian upper class woman.

- Madame DeFarge. Madame DeFarge is the other end of the good-evil spectrum although she has an explanation for her evil and desire for revenge. The image of Madame DeFarge knitting is, in addition to being one of the most famous images in British literature, the central image of the novel. Her knitting intimates the archetypal image of weaving to represent the threads of life, as suggested in the title of Part II, The Golden Thread.

- Ernest DeFarge. With a name signifying his role, Ernest DeFarge serves as a comparison and contrast with Madame DeFarge

- The Vengeance. The Vengeance is an allegorical characterA character who represents an abstract quality, creating two levels of meaning in a literary work., a character who represents an abstract quality, creating two levels of meaning in a literary work.

- Miss Pross. As Lucie is a stereotype of an upper class British woman, Miss Pross is a stereotype of a British working class woman, loyal and fiercely patriotic.

- Cruncher. The inclusion of a “resurrection man” amplifies, and in a subtle way satirizes, the theme of resurrection.

Cities as Characters

The title declares the story a tale of two cities. Paris and London become conveyances of theme: light and dark, good and evil, redemption and retribution.

Portraying London as a place of safety, of survival, even of sanity resonated with patriotic Victorian audiences, contributing to pride in the British Empire.

Themes

- Threads of destiny. The weaving or knitting motif serves as an archetypeAn image or symbol embedded in the collective unconsciousness of people from all cultures, an idea based on the psychological theory of Carl Jung., an image or symbol embedded in the collective unconscious of people from all cultures, an idea based on the psychological theory of Carl Jung. In mythology, the Fates weave, representing fate determining human destiny, gradually revealing the pattern of one’s life in their tapestry.

- Guilt and retribution. The French aristocracy is personified in St. Evrémondes, who in turn personifies guilt. Darnay is inextricably connected to the guilt as surely as he is related to St. Evrémondes, an example of the weaving together of various threads to form one’s destiny. Retribution is embodied in Madame DeFarge.

- Retribution and redemption. The contrast of retribution and redemption form a major theme of the novel, a theme in which almost all the characters play a role.

- The doppelganger. The word doppelganger, translated from German, literally means ‘double walker” or “double goer.” In folklore, the doppelganger is often a harbinger of death or an ill omen, not necessarily a physical double. Elements of the doppelganger in both senses function in A Tale of Two Cities.

Key Takeaways

- Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities was published as a serial novel, a popular form of publication in the Victorian Era.

- The novel is structured in three parts, each part with a title that helps to convey theme.

- In the well-known opening lines, Dickens uses literary devices such as anaphora, asyndeton, parallelism, and paradox.

- The novel’s characters include both developing and static characters, both types contributing to the development of theme.

- Major themes of the novel are threads of destiny, guilt and retribution, and retribution and redemption.

Exercises

Structure and Theme

Consider the themes conveyed by the three-part structure.

-

Part I Recalled to Life

-

Who is recalled to life? Consider the following characters:

- Dr. Manette

- Charles Darnay

- Sydney Carton

- Jarvis Lorry

- Miss Pross

- How are these characters “recalled to life”?

- What is the purpose of Cruncher and his occupation, “resurrection man”?

-

-

Part II The Golden Thread

- How does Lucie function as a “golden thread,” weaving the events?

- Could Madame DeFarge function as a “golden thread”?

- What are the literal and figurative purposes of Madame DeFarge’s knitting?

-

Part III The Track of a Storm

- What personal “storms” erupt in Part III?

- What public “storms”?

Characters

- Trace the development of Sydney Carton’s character from his dissipated state to his redemption. What forces affect his developing character?

- Compare Lucie, the stereotypical Victorian upper class woman, with Miss Pross, the stereotypical Victorian lower class woman.

- Why doesn’t Madame DeFarge anticipate Carton’s action?

- What explanation does the novel provide for Madame DeFarge’s evil? After learning the explanation, do her actions seem justified?

- In what ways and why is The Vengeance different from Madame DeFarge?

- In what ways do the two cities represent “poetic justice,” with the “good guys” ending up in England and the “bad guys” ending up in France?

- Compare and contrast Dickens’s portrayal of London and Paris with the Romantic poets’ depiction of the pastoral countryside and the industrialized city.

Images

- Identify images of light and dark throughout the novel. What themes do these images support?

- Locate references to footsteps throughout the novel. What is the purpose of these references? Also consider Dr. Manette’s shoemaking; explain how it symbolizes the path he makes for his own and Lucie’s fate.

- List instances of the spilling of wine throughout the novel. How do these incidents function literally in the plot and figuratively in reinforcing theme?

Themes

- How do references to Lucie’s hair connect to the “threads of destiny” motif?

- How and why is Darnay different from his relative St. Evrémondes? How do his decisions and actions contribute to a destiny different from his uncle’s?

- What role does Dr. Manette’s letter play in the theme of guilt and retribution?

-

Almost all the characters in the novel play a role in developing the theme of retribution and redemption. Identify which of the following characters represent retribution and which represent redemption. After compiling this initial list, reconsider each character to determine those who are more complex, who embody elements of both retribution and redemption.

- Darnay

- Carton

- Dr. Manette

- Lorry

- Minor characters: Cruncher, Barsad

-

Identify examples of the doppelganger and describe their function in the novel. Include the following examples:

- London-Paris

- Darnay-Carton

- Lucie-Madame DeFarge and/or Miss Pross-Madame DeFarge

Resources

General Information

- “Charles Dickens.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- David Perdue’s Charles Dickens Page.

- “Dickens in Context.” The British Library. includes videos and images.

- The Dickens Project. University of California.

Biography

- “Charles Dickens (1812–1870).” BBC History.

- “Charles Dickens—Biographical Information.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Charles Dickens: The Life of the Author.” Kenneth Benson. The New York Public Library.

A Tale of Two Cities

- “A Tale of Two Cities.” Discovering Dickens—A Community Reading Project. Stanford University.

- “Some Discussions of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

Text

- Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870. A Tale of Two Cities. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Project Gutenberg.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. A. L. Burt Company, Publishers, New York. 1890. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Video

- “Charles Dickens Animation.” BBC Home.

- “Virtual Guide for Charles Dickens Birthplace.” Portsmouth Museums and Records.

Audio

- “A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1812–1870).” LibriVox.

- “A Tale of Two Cities.” Charles Dickens. Lit2Go. Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida.

Images

- “Charles Dickens.” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.