This is “John Keats (1795–1821)”, section 6.12 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.12 John Keats (1795–1821)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Analyze Keats’s use of the sonnet form in “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” and “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.”

- Identify characteristics of Romanticism in Keats’s poetry.

- Compare Keats’s use of nature with other Romantic poets.

- Recognize and identify examples of the richness of imagery for which Keats’s is known in “The Eve of St. Agnes” and “To Autumn.”

Biography

Unlike Byron and Shelley, John Keats came from a working class background. His father, a stable keeper, died when Keats was eight years old; his mother died of tuberculosis, then called consumption, when he was 14. Keats left school to become an apothecary’s apprentice. He left the apprenticeship to study medicine but soon decided to abandon his studies to pursue writing poetry. Keats cared for his brother Tom during his illness and death from tuberculosis, so it is not surprising that Keats also contracted the illness. Because of his medical knowledge, he recognized that he had a fatal illness.

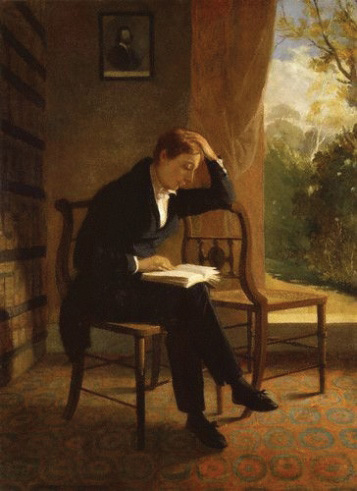

Portrait by Joseph Severn from Letters of John Keats to His Family and Friends.

ed. Sidney Colvin. Macmillan and Co., Limited. St. Martin’s Street, London, 1925

Keats became acquainted with other writers such as Shelley and literary figures such as Leigh Hunt, in whose journal Keats published his first poem. Keats’s early work was not well received. Several of Keats’s friends, in fact, blamed discouragement caused by the harsh criticism for hastening the poet’s death.

After his brother’s death and with his own health deteriorating, Keats moved into a house in Hampstead with his friend Brown. Through Brown, Keats met Fanny Brawne, the love of his life. The Brawne family rented the attached house next door to Brown’s house.

During the year he lived here, Keats produced his greatest poetry including “The Eve of St. Agnes,” “Ode to Psyche,” “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” “Ode to a Nightingale,” “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Ode on Melancholy,” “Lamia,” The Fall of Hyperion, and “To Autumn.” Many critics have noted that Keats produced more great poetry in a year than many poets produce in a lifetime.

Views of the interior of Keats’s house in Hampstead, London, now a museum.

Realizing that his health was failing, Keats decided to move to Rome, hoping that the warmer, drier climate would improve his condition. He traveled to Rome with his friend, artist Joseph Severn. They moved into rooms next to the Spanish Steps, rooms which now house the Keats-Shelley House museum.

Only a few months after his arrival in Rome, Keats died with his friend Severn in attendance and was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome. At his request, his name was not carved into his grave stone. Keats requested that his marker read, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” Severn, who was later buried next to Keats, and Brown decided to add the following inscription to the memorial:

This Grave contains all that was mortal, of a YOUNG ENGLISH POET, who on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his heart, at the Malicious Power of his enemies, desired these words to be Engraven on his Tomb Stone

Severn’s drawing of Keats on his death bed.

These words fueled stories that Keats’s death was hastened by his despair over the brutal critical reviews of his poetry. Shelley’s elegy Adonais includes verses attributing Keats’s death to his agitation over the reviews, also adding substance to the stories. A post-mortem, however, revealed that Keats’s lungs had been almost entirely destroyed by tuberculosis.

The graves of Keats and Severn in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

Texts

- “The Eve of St. Agnes.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from The Poetical Works of John Keats. London. Macmillan.1884.

- “The Eve of St. Agnes.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Ode to a Nightingale.” Keats-Shelley House. text and audio.

- “Ode to a Nightingale.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- The Poems of John Keats. Ed. E. De Selincourt. New York. Dodd, Mead and Co. 1909. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Poems Published in 1820 by John Keats. Ed. M. Robertson. Project Gutenberg.

- “To Autumn.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “To Autumn.” Keats-Shelley House. text and audio.

- “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.” Keats’ Literary Reputation. British Library. text and audio.

- “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

“On Seeing the Elgin Marbles”

Even as a very young man, Keats seemed tragically aware of death and of his own mortality, as might be expected in one who had suffered loss of immediate family members. Although the subject of this sonnet is the Elgin Marbles, the focus in the first line is on approaching death. In line 5, the poet compares himself to a sick eagle, looking at the sky, longing to fly, yet unable to do so. In contrast to his own brief life span, the marbles are centuries old, yet even they are marked and worn by time.

Video Clip 9

John Keats.wmv

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture about “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles.”

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

Yet ‘tis a gentle luxury to weep

That I have not the cloudy winds to keep

Fresh for the opening of the morning’s eye.

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an undescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old time—with a billowy main—

A sun—a shadow of a magnitude.

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

Yet ‘tis a gentle luxury to weep

That I have not the cloudy winds to keep

Fresh for the opening of the morning’s eye.

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an undescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old time—with a billowy main—

A sun—a shadow of a magnitude.

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

Yet ‘tis a gentle luxury to weep,

That I have not the cloudy winds to keep,

Fresh for the opening of the morning’s eye.

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an indescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old Time—with a billowy main—

A sun—a shadow of a magnitude.

“When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be”

“When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” is an English sonnet; Keats was more interested in form than many of the Romantic poets, which in turn made him interesting to many Victorian poets who experimented with form. The sonnet consists of three quatrains, each beginning with “when,” and a final couplet, which begins with “then.”

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high piled books, in charact’ry,

Hold like rich garners the full-ripen’d grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour!

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love!—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

“The Eve of St. Agnes”

“The Eve of St. Agnes” is a narrative poemA poem that tells a story., a poem that tells a story. It is also an example of the medieval revivalThe renewed interest in the Middle Ages evident in some Romantic literature., the renewed interest in the Middle Ages evident in some Romantic literature. During the 19th century, many writers idealized the Middle Ages; it seemed romantic and less complicated than the modern world. However, they often had a fairy tale view of medieval times, thinking only of knights in shining armor rescuing fair damsels in distress rather than recognizing the harsh, violent time period that it really was.

This story is set in the Middle Ages and is a type of Romeo and Juliet story of two feuding families and the children who love each other in spite of their families’ enmity. Ambiguity at the end of the story leaves readers to decide whether Madeline and Porphyro “live happily ever after” or whether they freeze in the winter night.

Central to the story is a medieval superstition concerning St. Agnes Eve. This type of superstition—a ritual that allows young girls to find out who their future husband will be—is common in many cultures. In America’s past there have been superstitions and folklore involving sleeping with a piece of wedding cake under your pillow, or peeling an apple and throwing the peel over your shoulder. In the Middle Ages, superstition specified a ritual which, if followed on St. Agnes Eve, would allow a girl to dream of her future husband. Note the specifics of the ritual in Stanza 6. Porphyro, aided by Madeline’s nurse, decides to take advantage of his knowledge that his beloved Madeline will be expecting to see a vision of her true love. Note in Stanza 35, however, how Madeline reacts to the real Porphyro compared with her dream.

“The Eve of St. Agnes” presents the reader with two contrasting worlds, separated by symbolic doors. The poem begins with a description of a harsh, cold landscape in which even nature suffers, focusing on the beadsman, near freezing to death, who prays for the family. A door opens, and the reader is ushered into a warm, colorful world inside the house where the main action takes place. Then in Stanza 41, a door opens again and the lovers leave the castle, taking with them any hint of love and warmth. The poem ends in images of death and cold.

“To Autumn”

SEASON of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

2

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

3

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

“Ode to a Nightingale”

While Keats lived in Brown’s Hampstead house, a plum tree grew next to the front door. One evening, Keats was sitting under the tree when he heard a nightingale singing from the tree.

The poem begins by focusing on the speaker, sick at heart and in spirit, envious of the bird’s happiness. The speaker searches for a way to escape the pain of living. In Stanza 2 he considers wine as a means of escape but rejects that possibility.

In Stanza 3, the speaker recognizes that wine will not make him forget the “weariness, the fever, and the fret” of living, hardships that the nightingale has never known. Even in poetry, the speaker does not find an escape from the cares of living. So burdened by the pain of life, the speaker confesses that he has at times been “half in love with easeful death.” He adds that this moment, enraptured by the beauty of the bird’s song, seems an even more tempting time to die. He realizes, however, that in death he would miss the small consolation of this beauty.

In Stanza 7, the speaker exclaims, “Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!” He recognizes that since ancient times people have been enchanted by this same song.

Finally, he imagines the bird flying across the meadow and river, leaving the speaker wondering if he had imagined or dreamed the entire experience.

Key Takeaways

- More interested in poetic form than many Romantic writers, Keats wrote sonnets.

- Keats’s “The Eve of St. Agnes” is an example of the medieval revival.

- Keats uses nature to express his themes, often themes concerning death.

Exercises

- What characteristics of Romanticism are evident in Keats’s poetry?

- How does Romantic mysticism appear in the works of Keats?

- How does Keats’s use of nature compare with that of other Romantic writers?

“When I Have Fears that I May Cease to Be”

- What does Keats mean when he writes, “When I have fears that I may cease to be”?

- The poet expresses a different fear in each quatrain. What are his three fears?

- His only consolation from his fears is expressed in the final couplet. What is it?

- Why does this poem seem especially sad when we know Keats’s biography?

“The Eve of St. Agnes”

- Keats is known for the richness of the descriptive imagery in his poetry. Compile a chronological list of the scenes in the poem, and list some of the description included in each scene. (For example, the first scene in the poem is outdoors, with the owl, the rabbit, and the frozen grass.)

- “The Eve of St. Agnes” is a poem of contrasts. List and explain contrasting ideas you find in the poem (for example, youth and old age, warmth and cold).

- Write a character sketch of Madeline, including a physical description, character traits, and actions and motives in the poem.

- Write a character sketch of Porphyro, including a physical description, character traits, and actions and motives in the poem.

- What do you think happened to the lovers?

Resources

Biography

- “Afterlife.” Presenting John Keats. Curated by Libby Chenault and Katherine Carlson, Rare Book Collection, Wilson Library. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- John Keats 1795–1821. Keats-Shelley House. includes images of Romantic writers, manuscripts, first editions.

- John Keats (1795–1821). Online Gallery: John Keats. British Library. includes images of Keats and of manuscripts.

- “The Life and Legacy of John Keats.” Presenting John Keats. Curated by Libby Chenault and Katherine Carlson, Rare Book Collection, Wilson Library. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- “Work and Reappraisal.” Presenting John Keats. Curated by Libby Chenault and Katherine Carlson, Rare Book Collection, Wilson Library. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Texts

- “The Eve of St. Agnes.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from The Poetical Works of John Keats. London. Macmillan.1884.

- “The Eve of St. Agnes.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Ode to a Nightingale.” Keats-Shelley House. text and audio.

- “Ode to a Nightingale.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- The Poems of John Keats. Ed. E. De Selincourt. New York. Dodd, Mead and Co. 1909. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Poems Published in 1820 by John Keats. Ed. M. Robertson. Project Gutenberg.

- “To Autumn.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “To Autumn.” Keats-Shelley House. text and audio.

- “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.” Keats’ Literary Reputation. British Library. text and audio.

- “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Video

- “John Keats.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- Keats-Shelley House. virtual tour of the house in Rome where Keats was living when he died, now the location of the Keats-Shelley Museum, including information about Keats’s time in Rome

- “Keats and Brawne: The Romance and Love Letters.” Woman’s Hour. BBC 4.

- “Keats’s ‘To Autumn.’” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

Audio

- “Bright Star” Panel Discussion. Stuart Curran, Christopher Ricks, Timothy Corrigan and Susan Wolfson At the New York Public Library Performing Arts Library, 13 September 2009. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “Chris Dombrowski Reads ‘To Autumn’ by John Keats.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland. text and audio.

- “The Eve of St. Agnes.” LibriVox.

- “Keats, Shelley, and the ‘Bright Star.’” Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi Lecture at the University of Loyola Chicago, 19 October 2006. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “Ode to a Nightingale.” Keats-Shelley House.

- “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles.” LibriVox.

- “The Posthumous Life.” Keats-Shelley House. audio drama of Keats’s last days in Rome.

- “To Autumn.” Keats-Shelley House.

- “Tom Thompson Reads ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ by John Keats.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland. audio and text of the poem and commentary.

- “Wesley McNair Reads ‘When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be’ by John Keats.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland. audio of the poem and commentary. Additional recordings of this sonnet by Carey Salerno and Ravi Shankar. text and audio.

- “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be.” Keats’ Literary Reputation. British Library. text and audio.

Concordance

- “An Electronic Concordance to Keats’s Poetry.” Electronic Ed. Noah Comet. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- John Keats The Odes of 1819 Web Concordance. The Web Concordances.

Text Image

- “The Eve of St. Agnes: a Poem / by John Keats; With a Preface Written for It by Edmund Gosse. Edition limited to 800 copies made upon L.L. Brown’s H.M. paper…printed…from plates made from drawings for each page, designed & lettered by Ralph Fletcher Seymour. Hathi Trust Digital Library.