This is “Samuel Johnson (1709–1784)”, section 5.5 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.5 Samuel Johnson (1709–1784)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the various literary roles and the prominent place Samuel Johnson held in 18th-century literary society.

- Interpret Johnson’s “The Vanity of Human Wishes” as a criticism of 18th-century society.

Biography

Primarily known during his lifetime as a lexicographer and a journalist, Samuel Johnson was also a poet and a leading figure in late 18th-century literary circles. The son of a bookseller, Johnson lacked the funds to complete his degree at Oxford. However, he read voraciously at home and began his college career at Oxford by impressing his teachers and fellow students with his knowledge. After establishing himself as a journalist, Johnson was hired to compile a dictionary which became one of the most well-known of English dictionaries.

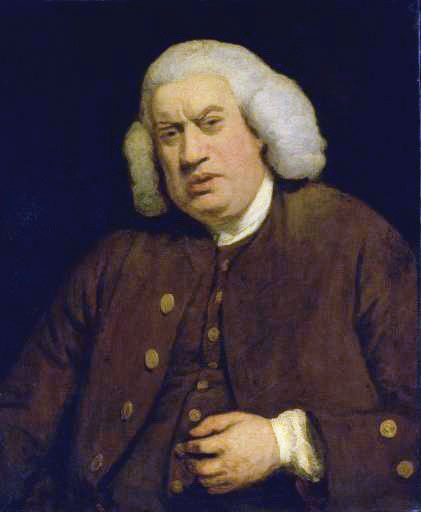

Portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

“The Vanity of Human Wishes”

Text

- Dr. Johnson’s Works: Life, Poems, and Tales, Volume 1 by Samuel Johnson. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Facsimile of the 1749 edition by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Renascence Editions. R. S. Bear. University of Oregon.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto.

Johnson’s “The Vanity of Human Wishes” employs many of the characteristics of neoclassical poetry: it is patterned after the classical Latin works of Juvenal; it uses the formal, highly structured closed heroic couplet; it exalts reason; it uses personificationgiving human characteristics to inanimate objects or abstract qualities [giving human characteristics to inanimate objects or abstract qualities].

The first stanza presents the main idea of the poem: that life is like a maze which each individual stumbles through without a guide. The poem is then developed like an essay: each “vain wish” serves as a topic sentence developing the thesis. Each topic sentence is, in turn, developed with specific examples. This poem is often difficult for modern readers because many of the examples are allusions to people, places, and events familiar to the 18th century audience but not to a current audience. However, the main ideas—the vain wishes—are equally relevant.

The copy of the poem from Representative Poetry Online provides notes which explain many of the unfamiliar references.

Key Takeaways

- A key figure in the 18th-century literary world, Samuel Johnson was a lexicographer, journalist, poet, diarist, essayist, dramatist, and writer of short fiction.

- Johnson’s work exemplifies the characteristics of neoclassicism.

Resources

General Resources

- “Samuel Johnson: A Tricentennial of Johnson’s Birth.” Clark Library. University of California, Los Angeles.

- “Samuel Johnson’s ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes.’” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow. Brown University.

Biography

- “Samuel Johnson (1709–1784).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. XV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 471–2.

- “Samuel Johnson (1709–1784).” Historic Figures. BBC History.

- “Samuel Johnson: An Introduction.” The Victorian Web. David Cody. Hartwick College.

Text “The Vanity of Human Wishes”

- Dr. Johnson’s Works: Life, Poems, and Tales, Volume 1 by Samuel Johnson. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Facsimile of the 1749 edition by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Renascence Editions. R. S. Bear. University of Oregon.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto.

Audio

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” The PennSound Anthology of Restoration and 18th-Century Verse. edited and performed by John Richetti. PennSound Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing.

Daisy

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Internet Archive.