This is “Alexander Pope (1688–1744)”, section 5.3 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.3 Alexander Pope (1688–1744)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define satire and apply the definition to Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock.”

- Trace the historical events that led to the writing of “The Rape of the Lock.”

- Evaluate Pope’s use of satire in “The Rape of the Lock.”

After the Great Fire of London aroused anti-Catholic feeling that had simmered since the reign of James II, Parliament passed the first of two Test Acts, laws that banned Roman Catholics and nonconformists (Protestants not members of the Church of England, such as Puritans) from holding public office, serving in the military, attending universities, or essentially having any part in public life. Born into a Roman Catholic family, Alexander Pope’s education was limited to occasional tutoring from priests and his own regimen of study. Pope suffered from what many experts now believe to be tuberculosis of the bone, resulting in a deformity in his back and stunted growth. Both his religion and his physical disabilities barred him from the kind of participation in court life that resulted in patronage that other poets enjoyed. With his family’s financial security from his father’s business, Pope was able to devote enough time to his writing, translating, and editing to begin earning a comfortable living. He soon established himself as one of the prominent neoclassic writers.

Portrait by Jean-Baptiste van Loo.

Text

- “The Rape of the Lock.” Electronic Classics Series. Jim Manis, Senior Faculty Editor. Pennsylvania State University.

- “The Rape of the Lock.” S. Constantine. University of Massachusetts. with annotations.

- “The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems by Alexander Pope.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope.” Edited by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “Selected Poetry of Alexander Pope.” Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto.

“The Rape of the Lock”

Like Swift, Alexander Pope chose satire as his method for addressing and possibly correcting a difficult situation. Unlike Swift, Pope addresses a personal situation.

Within the society of aristocratic Roman Catholic families, a young gentleman, Lord Petre, furtively cut a lock of hair from a beautiful young woman he was courting, Arabella Fermor. Arabella and her family were incensed at the “assault” and refused to associate with Lord Petre and his family, causing a rift within the social circle of Catholic families. A mutual friend John Caryll suggested that Pope write a humorous poem that might encourage the families to take the situation less seriously and to reconcile.

Heroic Couplet

A heroic couplettwo lines of poetry in iambic pentameter that rhyme is two lines of poetry in iambic pentameter that rhyme. Neoclassical writers favored this structured, symmetrical verse form. Pope uses the highly complex closed heroic coupleta rigidly structured verse form consisting of two lines, each iambic pentameter, which rhyme and which form a complete thought, a rigidly structured verse form consisting of two lines, each iambic pentameter, which rhyme and which form a complete thought.

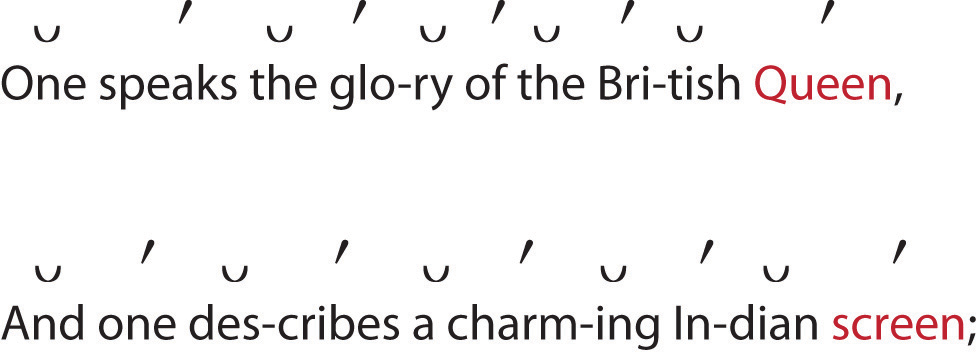

Figure 5.4

These two lines in Figure 5.4 are from Canto 3, lines 13–14. Note that each line is iambic pentameter, the two lines rhyme, and the semi-colon (end punctuation) indicates a complete thought.

Mock Epic

“The Rape of the Lock” is a mock epica poem which uses the characteristics and conventions of an epic but for a humorous and satirical purpose rather than a serious purpose, a poem which uses the characteristics and conventions of an epic but for a humorous and satirical purpose rather than a serious purpose. Even the title ironically suggests a serious crime when the offense is actually cutting a lock of hair.

- An epic states the theme at the beginning of the poem. The first two lines of Canto 1 follow the convention: “What dire offense from amorous causes springs, / What mighty contests rise from trivial things, / I sing.…” The word trivial epitomizes the theme, and the theme in turn leads to the choice of form, the mock epic which treats a trivial subject as if it were of epic importance. In contrast to the epic Paradise Lost, in which the theme is nothing less than the creation and fall of the human race, Pope’s mock epic highlights human superficiality and vanity.

- An epic invokes a muse: Pope’s muse is not a Greek god or the Holy Spirit, Milton’s muse; his muse is another human, John Caryll who asked him to write the poem.

- The supernatural forces are not God, angels, and demons of Paradise Lost but the sylphs whose duties are to guard Belinda’s hair and jewelry.

- The epic battles are reduced to card games. The preparation for battle takes place at Belinda’s dressing table and is presented in diction suggestive of religious rites (see Canto 1 lines 121–148). The Baron also prepares for battle by praying at his altar to love (see Canto 2 lines 35–46).

- The valiant feats of courage become clipping a lock of hair, threatening the Baron with a hairpin, and making him sneeze with a pinch of snuff.

Another technique Pope employs to convey his satirical point is the literary device called zeugmathe use of a word to apply to two disparate situations, the use of a word to apply to two disparate situations. For example, Canto 2, lines 105–110 present serious tragedies the sylphs fear might happen to Belinda juxtaposed with trivial possibilities:

Sidebar 5.2.

Whether the nymph shall break Diana’s law,

Or some frail china jar receive a flaw,

Or stain her honor, or her new brocade

Forget her prayers, or miss a masquerade.…

Belinda’s losing her virtue becomes the equivalent of an ornamental jar being cracked. Staining her honor becomes the equivalent of staining her dress. The effect is to emphasize the triviality of aristocratic values, a world in which marring one’s appearance by losing a single lock of hair is considered as consequential as a rape.

Key Takeaways

- Alexander Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock” exemplifies Horatian satire.

- “The Rape of the Lock” is a mock epic.

- “The Rape of the Lock” is written in closed heroic couplets, a verse form that embodies the structure and symmetry admired by neoclassicists.

Exercises

- Review the list of epic characteristics and conventions in the information about Milton’s Paradise Lost. In addition to the examples given, identify instances in “The Rape of the Lock” in which Pope trivializes epic conventions to create a mock epic.

- Describe Belinda and the Baron in Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock.”

- What are the objects of satire in “The Rape of the Lock”?

- In what ways could Pope’s work be characterized as Horatian satire in contrast with Swift’s Juvenalian satire?

- What parallels do you find in Milton’s epic Paradise Lost and Pope’s mock epic?

- Pope writes about aristocratic society in “The Rape of the Lock.” How would you compare/contrast the families involved in this situation with the aristocratic British and Irish people Swift alludes to in “A Modest Proposal”?

Resources

Biography

- “Alexander Pope (1688–1744).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. XXII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 87.

- “Alexander Pope.” Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

- “Alexander Pope.” The Twickenham Museum.

Text

- “The Rape of the Lock.” Electronic Classics Series. Jim Manis, Senior Faculty Editor. Pennsylvania State University.

- “The Rape of the Lock.” S. Constantine. University of Massachusetts. with annotations.

- “The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems by Alexander Pope.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope.” Edited by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “Selected Poetry of Alexander Pope.” Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto.

Background Information

- “Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock: An Introduction.” David Cody. Hartwick College. The Victorian Web.

- “The Story Behind the Poem.” The Rape of the Lock Homepage. S. Constantine. University of Massachusetts.

Heroic Couplet

- “The Heroic Couplet: Its Rhyme and Reason.” J. Paul Hunter. University of Chicago. Lecture presented at the National Humanities Center.

- “Heroic Couplet.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Heroic Couplets.” Jack Lynch. Glossary of Literary and Rhetorical Terms. Rutgers University.

- “Heroic Couplets.” Erik Simpson. Connections: A Hypertext Resource for Literature. Grinnell College.

Mock Epic

- “High Burlesque: Mock Epic (Mock Heroic); Parody.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Zeugma.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Zeugma.” Literary Terms and Definitions. Dr. L. Kip Wheeler. Carson-Newman College.