This is “The Restoration and 18th Century”, section 5.1 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.1 The Restoration and 18th Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the two key tragedies of 1665–1666 and their effects on the literature of the Restoration era.

- Analyze features of the Enlightenment which distinguish the Age of Reason from preceding time periods and which affect neoclassical literature.

- Characterize the developments of the English language during the 18th century.

- Recognize key forms of literature produced in the Restoration and 18th century.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell, his son Richard Cromwell attempted to assume his father’s leadership position but soon proved unequal to the task. Negotiations began between the English Parliament and the son of the executed King Charles I. In 1660 the monarchy was restored, and Charles II became king. Having escaped to France following his father’s execution, Charles II had found refuge in the court of France, and when he returned to England brought with him a love of an extravagant, frivolous lifestyle that many, accustomed to the Puritan era, found offensive. Others delighted in the less repressive behaviors the new king encouraged.

Great Fire of London by Lieve Pietersz. Verschuier.

Only five years after the Restorationthe reestablishment of the monarch in England after the Puritan Revolution, the reestablishment of the monarch in England after the Puritan Revolution, England suffered an outbreak of plague. Modern estimates suggest that around 100,000 people died in London alone. Then in 1666, the Great Fire of London devastated the city, destroying over 13,000 houses, significant structures such as St. Paul’s Cathedral and the Royal Exchange, many warehouses full of goods, and businesses. The BBC History site allows viewers to see the same two engravings side by side in order to compare the before and after scenes in its “Great Fire of London Skyline Animation.” Luminarium reproduces a painting of London on fire, an engraving of St. Paul’s burning, and a map of the fire’s progress.

The Monument—monument to the Great Fire of London 1666, designed by Christopher Wren.

Some considered these two tragedies acts of God, punishment, according to some, for destroying God’s established order, the Great Chain of Being, by executing the divinely appointed King Charles I. According to others, the punishment was for abandoning the Puritan government and returning a licentious king to power.

Almost immediately suspicion of setting the fire fell upon the Roman Catholics. With memories of the Gunpowder Plot and the religious persecution present since the time of Henry VIII and the Reformation, many Protestants were quick to accuse Catholics of a plot to destroy London.

Queen Mary II and King William III.

Upon the death of Charles II, his brother James succeeded as King James II. Because James had earlier publicly converted to Roman Catholicism, the religious turmoil of the preceding century was renewed. As a result, Parliament forced James II to abdicate the throne and offered the crown to his daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange. Her uncle King Charles II had arranged Mary’s marriage to William of Orange, whose mother was a sister of Charles II and James II and who was a staunch Protestant. In what was known as the Glorious Revolution, a peaceful revolution, William and Mary replaced James II on the throne and ensured the dominance of the Protestant religion in England. William and Mary also agreed to a stronger role for Parliament in the governing of Great Britain. The age of the absolute monarch had ended.

The Enlightenment

The 18th century was the age of the Enlightenmentthe Age of Reason which emphasized reason, rational thinking, and order or the Age of Reason. In part a reaction against the chaos that had characterized the preceding centuries, Enlightenment thought emphasized reason, rational thinking, and order. One facet of the Enlightenment, the scientific revolution, began at the close of the Middle Ages and marked a profound change in thinking of natural phenomena as events with rational explanations rather than supernatural causes. Empirical observation and the concept of an orderly world, set up by God and run according to His laws of nature, governed philosophical thought as well as the technological development that led to the Industrial Revolution. The British Museum provides an online tour of London in 1753, the year the museum opened, an indication of the interest in science and learning. The online tour includes pictures of early manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution.

The orderly nature of the world was no longer the medieval Great Chain of Being. Instead philosophers began to postulate that all men were created equal and with innate human rights, ideas which led to both the American and French Revolutions in the 18th century. This idea is evident in the English Parliament’s insistence that William and Mary grant more authority to Parliament, the representatives of the English people.

In literature, the Enlightenment appears as neoclassicismliterally means new classicism; emphasizes order, symmetry, elegance, and structure in the arts, including literature, which literally means new classicism and emphasizes order, symmetry, elegance, and structure in the arts, including literature. As apparent in the term neoclassicism, neoclassical writers, artists, and architects looked back to ancient Greece and Rome for classical forms featuring symmetry and geometrical precision in everything from poems to buildings.

Sidebar 5.1.

St. Paul’s Cathedral in London is an example of neoclassical architecture. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, Sir Christopher Wren was commissioned to re-build many of the city’s churches, including St. Paul’s Cathedral. Note the symmetry of the building and the use of columns and the triangular tympanum, all features of classical Greek architecture.

Christopher Wren also remodeled one part of Hampton Court Palace, built during the reign of Henry VIII, for William and Mary. Note the symmetry of Hampton Court Palace in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1

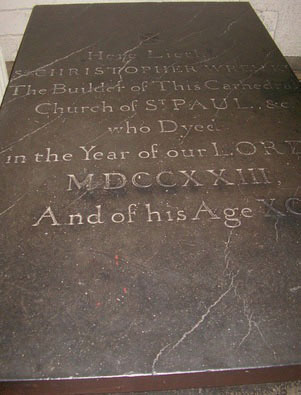

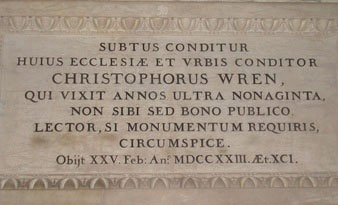

When he died in 1723, Wren was buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Although it might be expected that one of the world’s most famous architects and the person who designed and personally supervised the building of the Cathedral would have a grand tomb, Wren requested a modest grave site and memorial plaque.

Figure 5.2

The black stone slab in Figure 5.2., located in an inconspicuous corner, covers Wren’s grave. The plaque pictured in Figure 5.3. is located on the wall above the black slab and is engraved with the epitaph: “Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you,” indicating that St. Paul’s Cathedral itself is Wren’s monument.

Figure 5.3

Language

The Restoration and 18th century was a time of standardization of the English language. During the Elizabethan Age, Shakespeare created new words and new expressions, and spelling was erratic. During the early 17th century, the metaphysical poets created elaborate, unusual metaphors. In the 18th century, writers favored a more common sense, prescriptive approach to language. Dr. Samuel Johnson created one of the early and most influential English dictionaries. One of the goals of Johnson’s dictionary was to help create rules of grammar, usage, and spelling previously lacking in the English language, an idea in line with the preference for structure that characterized neoclassicism and with the scientific approach to all subjects typical of the Age of Reason. Although the feudal system had long ago faded into the past, British society of the 18th century maintained a strict social class system reflected in the language.

Literature

Restoration Drama

With the Restoration of the monarchy came the restoration of the theater. After being shuttered during the Puritans’ rule, theatres opened almost immediately. Charles II hired companies of actors to provide court entertainment, as his grandfather James I had been patron of Shakespeare’s troop The King’s Men. Plays from the Elizabethan Age were revived and new dramatists emerged although none produced work of the high caliber of Shakespeare’s age. Among the new generation of playwrights were several women, most notably Aphra Behn. Another innovation in 18th-century theater was that women were allowed on stage.

During the 18th century, the comedy of mannersa play which presents aristocratic characters, exaggerating their obsession with high society manners, social position, fashion, and wealth, a play which presents aristocratic characters, exaggerating their obsession with high society manners, social position, fashion, and wealth, flourished. These plays are noted for their witty dialogue and satiric manner. The plots generally involve amorous, usually scandalous, affairs and the characters’ amoral reactions to them. Familiar stock characters were the fop or dandy, a vain young man obsessed with fashion, and the rake, a young man devoted to wine, women, and scandalous conduct. Richard Sheridan’s “The Rivals” and “The School for Scandal” and Oliver Goldsmith’s “She Stoops to Conquer” were among the more popular comedies of manners.

The Novel

The 18th century gave birth to the novelan extended fictional prose narrative, an extended fictional prose narrative, as a form of literature. Daniel DeFoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders are considered the first novels. DeFoe’s works were followed by Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novela novel written in the form of a series of letters (a novel written in the form of a series of letters) Pamela, and Henry Fielding’s Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones. The novel continued to develop into a major literary form of the 19th century.

Diarists

Just as many people in the 21st century record the details of their daily lives on Facebook or Twitter, people in the 18th century recorded their lives in diaries, works which now provide information and insight into the events of that time period. Some of the more well-known diarists were Samuel Pepys, John Evelyn, Daniel DeFoe, and Celia Fiennes.

Pepys provides detailed descriptions of London during the plague and the fire as well as daily life in the Restoration era.

Covering a much longer period of time, John Evelyn writes a more formal diary from the perspective of a conservative supporter of the monarchy and of the Church of England.

Although actually a fictional account of the plague, Daniel DeFoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year parallels Pepys’s accounts of the plague while giving even more detail. DeFoe’s A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain describes several journeys DeFoe made early in his life, providing a comprehensive picture of pre-Industrial Revolution England.

In a similar fashion but a much more daring endeavor, Celia Fiennes, the daughter and granddaughter of Puritan supporters, wrote what is perhaps the most unusual and interesting of the 18th century diaries. Not published until 1888, her journals document trips she made through every county in England as well as into parts of Scotland and Wales. Riding side saddle, Fiennes traveled most of the time with only one or two servants as companions. For a woman to travel without a father or husband as escort was extraordinary in this time period and dangerous as well. Fiennes records encounters with highwaymen and falls from her horse as she forded rivers and traveled England’s rough roads. Ostensibly traveling for her health, Fiennes observed local industries and described the landscape, both natural and manmade. Her family’s Puritan views are apparent in her comments about the churches, clergymen, and local religious conventions.

Key Takeaways

- The Great Fire of London in 1666 and another outbreak of the plague affected the literature produced in the Restoration and 18th century.

- Neoclassicism, a facet of the Enlightenment era, produced highly structured, formal literature modeled on classical Greek and Roman literature.

- During the 18th century, the English language became more standardized and prescriptive.

- The first English dictionaries, particularly Dr. Samuel Johnson’s dictionary, were produced during the 18th century.

- The Restoration brought about the re-opening of the theatres and the development of new drama, including the comedy of manners.

- The novel had its origins in the 18th century.

- Journals and diaries were an important form of literature in the Restoration and 18th century.

Resources

Background

The Monarchy

- “1660–1685: Restoration of Stuart Dynasty & Reign of Charles II.” Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “Charles II of England (1630–1685).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol XV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 142.

- “English Civil War: The Glorious Revolution.” E.L. Skip Knox. Boise State University.

- “The Forgotten Tricentennial: England’s Glorious Revolution.” Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Professor of Law, University of Georgia School of Law. Feb. 14, 1989.

- “The Glorious Revolution.” David Cody, Hartwick College. The Victorian Web.

- “James II of England (1633–1701).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol XV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 142.

- William III and Mary II (1689–1702 AD). Britannia.com.

The Plague

- “The Great Plague of 1665.” Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “The Great Plague of 1665–6.” Education. The National Archives.

- “The Great Plague of London, 1665.” Contagion: Historic Views of Diseases and Epidemics. Harvard University Library Open Collections Program.

- “The Plague Book.” Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. University of Virginia. digital images of a 16th-century plague book.

The Great Fire of London

- “The Great Fire of London, 1666.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Great Fire of London: Skyline Animation.” BBC History. BBC.

- “London’s Burning: The Great Fire of London 1666.” Museum of London.

The Enlightenment

British Museum Series of Online Tours on the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment

- “Age of the Enlightenment.” Gerhard Rempel. Western New England College.

- “The Enlightenment.” Prof. Norman West. Suffolk Community College.

- “The European Enlightenment: The Eighteenth Century.” Richard Hooker. 1996. World Civilizations: An Internet Classroom and Anthology. Washington State University.

- “The European Enlightenment: The Scientific Revolution.” Richard Hooker. 1996. World Civilizations: An Internet Classroom and Anthology. Washington State University.

- “Introduction to Neoclassicism.” Lelia Melani. Brooklyn College. City University of New York.

- “The Neoclassic Age.” Sarah E. Selby. Waycross College.

- “Neoclassicism: An Introduction.” The Victorian Web.

- “Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723).” Historic Figures. BBC History. BBC.

Language

- “1755—Johnson’s Dictionary.” Learning: Dictionaries and Meanings. British Library.

- “The Age of Dictionaries.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “The English Language in the 18th Century.” Katya Gifford. Humanities Web.

- “Johnson’s Dictionary.” Clark Library. University of California, Los Angeles.

- “Johnson’s Dictionary.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “The King’s English: Eighteenth-Century Language.” Education. Colonial Williamsburg. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- “Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary: Sources and Editions.” Vassar College Libraries. Archives and Special Collections.

Restoration Drama

- “Aphra Behn (1640–1689). Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Restoration Drama.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Martha Fletcher Bellinger. A Short History of the Theatre. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1927. 249–59.

- “The Restoration Drama.” Theatre Database. rpt. from William Vaughn Moody and Robert Morss Lovett. A History of English Literature. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902.

- “Types of Comedy.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “Women in the Theater After the Restoration.” Ruth Nestvold. The Aphra Behn Page.

The Novel

- “The History of the Novel.” Dr. Agatha Taormina. Northern Virginia Community College.

- “The Novel.” Lelia Melani. Brooklyn College. City University of New York.

Diarists

- “Diaries of the Seventeenth Century.” Mark Knights. Feb. 17 2011. BBC History.

Samuel Pepys

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Phil Gyford. daily entries from Pepys’s diaries and a subject index.

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys by Samuel Pepys. Project Gutenberg.

- “Sex, Lice and Chamber Pots in Pepys’ London.” Liza Picard. 17 Feb. 2011.BBC History. BBC.

- “Samuel Pepys (1633–1703).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Daniel DeFoe

- A Journal of the Plague Year, written by a citizen who continued all the while. Project Gutenberg.

- “Voyage Narratives.” Daniel DeFoe. The Collection of the Lilly Library. Indiana University, Bloomington.

John Evelyn

- “The Diary of John Evelyn.” Internet Archive. California Digital Library.

- “John Evelyn: On Restoration and Revolution.” John Halsall. Internet Modern History Sourcebook.

Celia Fiennes

- “Celia Fiennes: Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary.” A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth.

- “Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary Being the Diary of Celia Fiennes.” A Celebration of Women Writers. University of Pennsylvania Libraries.