This is “Andrew Marvell (1621–1678)”, section 4.3 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

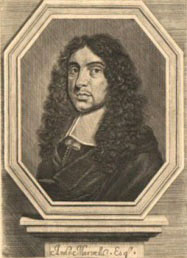

4.3 Andrew Marvell (1621–1678)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Analyze characteristics of metaphysical poetry in the works of Andrew Marvell.

- Recognize the effects of the English Civil War on Marvell’s production of literature.

- Explain the carpe diem philosophy as seen in “To His Coy Mistress.”

Biography

The son of a clergyman, Andrew Marvell was educated at Cambridge University. After working as a tutor and traveling extensively, Marvell served with John Milton in government posts and may have been instrumental in helping Milton avoid severe punishment, even a death sentence, after the Restoration. Marvell was, for a time, a supporter of King Charles I, but he then changed his allegiance to Oliver Cromwell and the commonwealth government. During the Interregnum, Marvell was elected as a Member of Parliament representing his hometown of Hull. He wrote several poems praising Oliver Cromwell and, after the Restoration, works critical of the court of Charles II even though his earlier work honored the reign of Charles I.

Statue of Andrew Marvell in Trinity Square in Marvell’s hometown of Hull, England—Trinity Square is bordered on one side by Trinity Church where Marvell’s father was a clergyman and on another side by the 16th-century building where Marvell attended grammar school.

“To His Coy Mistress”

Andrew Marvell is considered one of the metaphysical poets. Like John Donne, he wrote poems that relied on metaphysical conceits, the witty, elaborate comparisons that characterize metaphysical poetry. Also like Donne, many of his poems debate spiritual issues and the transitory nature of life. Even the poem that is probably Marvell’s best known, “To His Coy Mistress,” soon turns from seduction to metaphysical speculation. The poem is a seduction poem and a statement of carpe diema Latin phrase translated as “seize the day”, a Latin phrase translated as “seize the day.” The carpe diem philosophy encourages living life to the fullest in the present moment—the “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you die” outlook on life.

“To His Coy Mistress”

| Had we but world enough, and time, | |

| This coyness, lady, were no crime. | |

| We would sit down and think which way | |

| To walk, and pass our long love’s day; | |

| Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side | |

| Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide | |

| Of Humber would complain. I would | |

| Love you ten years before the Flood; | |

| And you should, if you please, refuse | |

| Till the conversion of the Jews. | |

| My vegetable love should grow | |

| Vaster than empires, and more slow. | |

| An hundred years should go to praise | |

| Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; | |

| Two hundred to adore each breast, | |

| But thirty thousand to the rest; | |

| An age at least to every part, | |

| And the last age should show your heart. | |

| For, lady, you deserve this state, | |

| Nor would I love at lower rate. | |

| But at my back I always hear | |

| Time’s winged chariot hurrying near; | 22 |

| And yonder all before us lie | |

| Deserts of vast eternity. | |

| Thy beauty shall no more be found, | 25 |

| Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound | |

| My echoing song; then worms shall try | |

| That long preserv’d virginity, | |

| And your quaint honour turn to dust, | 29 |

| And into ashes all my lust. | |

| The grave’s a fine and private place, | |

| But none I think do there embrace. | |

| Now therefore, while the youthful hue | |

| Sits on thy skin like morning dew, | |

| And while thy willing soul transpires | |

| At every pore with instant fires, | 36 |

| Now let us sport us while we may; | |

| And now, like am’rous birds of prey, | |

| Rather at once our time devour, | |

| Than languish in his slow-chapp’d power. | |

| Let us roll all our strength, and all | |

| Our sweetness, up into one ball; | |

| And tear our pleasures with rough strife | |

| Thorough the iron gates of life. | |

| Thus, though we cannot make our sun | |

| Stand still, yet we will make him run. |

William Holman Hunt The Hireling Shepherd.

Marvell’s poem urges a young woman to give in to love-making while she is young and desirable. The speaker of this poem begins his persuasive speech by telling her that her coyness would be acceptable if the couple had unlimited time. But he emphasizes the passing of time with the well-known image of “time’s winged chariot hurrying near” (line 22). He pictures the young woman in her tomb where she will no longer be beautiful (line 25) and where her “quaint honor” will “turn to dust” (29). The third and last stanza begins with the word “now,” emphasizing the need to enjoy life’s physical pleasures before death steals them. Now, while she is beautiful and their youthful passions spring into “instant fires” (36), they should consume their time by making full use of it while they have time and youth. The speaker, in the final couplet, notes that while they cannot make time (“our sun”) stand still, they can race against time by using their time to the utmost. Also suggested is the familiar idea that time flies when a person is enjoying him/herself, indicating that the sun will run quickly through the day if they are engaged in the pleasurable physical activity the speaker advocates.

Key Takeaways

- Andrew Marvell is a metaphysical poet whose poetry displays the typical characteristics of metaphysical poetry.

- Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” exemplifies the carpe diem tradition.

Exercises

- Review the list of characteristics of metaphysical poetry in the section on John Donne. What examples of those characteristics do you find in “To His Coy Mistress”?

- This poem is a seduction poem, an attempt by the speaker to persuade a young woman to make love with him. What arguments does he use to try to persuade her?

- How convincing do you consider his argument?

Resources

Biography

- “Andrew Marvell (1621–1678).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Andrew Marvell.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets.

- “Andrew Marvell.” rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume VII. Cavalier and Puritan. Bartleby.com.

- “Andrew Marvell: Chronology of Important Dates.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Text

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Annotations by Dr. K. Wheeler. Carson-Newman College.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Commentary by Michael Weiser. Thomas Nelson Community College.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” “Marvell, Andrew. Miscellaneous Poems.” Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Works of Andrew Marvell.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Audio

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Project Gutenberg.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” LibriVox.