This is “The Early Seventeenth Century”, section 4.1 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.1 The Early Seventeenth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the political and religious turmoil that influenced the literature of the early 17th century.

- Identify the contributions of Shakespeare and the King James Bible to early modern English, the language of the 17th century.

- Define and compare metaphysical poetry and cavalier poetry.

- Recognize the effects of the Puritan movement on drama and the theatre.

Political and Religious Controversy

In the sixteenth-century Tudor era, the religious turmoil that characterized the English Reformation under Henry VIII and continued, particularly during the reign of his daughter Queen Mary I, ameliorated during the reign of Elizabeth I. James I of England and VI of Scotland succeeded the childless Elizabeth, initiating the Stuart line of rulers. England’s religious struggles continued into the Stuart era, within forty years culminating in the English Civil War.

Only two years after James I came to the throne in 1603, Catholic activists attempted to assassinate him in what came to be known as the Gunpowder Plot. Barrels of gunpowder were planted underneath the Houses of Parliament and were set to be detonated while James I was present to open Parliament’s session. The goal was to kill the King and most if not all the Lords, thus throwing England into chaos and allowing an opportunity to establish a Catholic realm. However, the plan was discovered and the gun powder found, guarded by Guy Fawkes. The BBC presents a brief computer-generated video that portrays the history of the Gunpowder Plot.

Van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I.

When Charles I succeeded his father James I as king, he continued the objectionable policies of his father and, in fact, worsened the religious controversy by marrying a Roman Catholic French princess. Charles I himself favored the more formal services of the Anglican church angering those who wanted to “purify“ the Church of England. Thus he managed to alienate all religious factions—Catholic, Anglican, and Puritan.

The controversies that led to the English Civil War were both political and religious. In the political realm, James I and his successor Charles I insisted on the divine right of kings—the belief that kings were chosen by God and answered to no one but God, a theory that included the monarch’s right to rule without parliamentary intervention. On the religious front, in addition to the continuing strife between Protestant and Roman Catholic were added the additional demands of Protestant reformers who demanded reforms within the Church of England and the right to worship as dissenting organized religions. Against the monarch’s belief in the divine right of kings stood the growing conviction that Parliament should have greater influence on governmental decisions.

The Puritan Revolution (The English Civil War)

Member of Parliament Oliver Cromwell distinguished himself as a radical Puritan, organized and led a cavalry regiment of Parliament forces, and quickly rose to the leadership of the Puritan Revolution. Cromwell, a leading force in convincing Parliament to raise an army against the king, led the movement to execute Charles I.

Statue of Oliver Cromwell outside the British Houses of Parliament.

In 1649, Charles I was executed. Parliament’s House of Commons abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords, declaring England a Commonwealth. A few years later, Oliver Cromwell was named Lord Protector. The years between 1649 and 1660 were known as the Interregnum—literally meaning the time between kings. Upon Cromwell’s death, although Cromwell’s son assumed his father’s government position, the Commonwealth began to crumble under the son’s inept leadership. In 1660, Charles II, son of the executed king, assumed the throne and Britain’s monarchy was restored.

Language

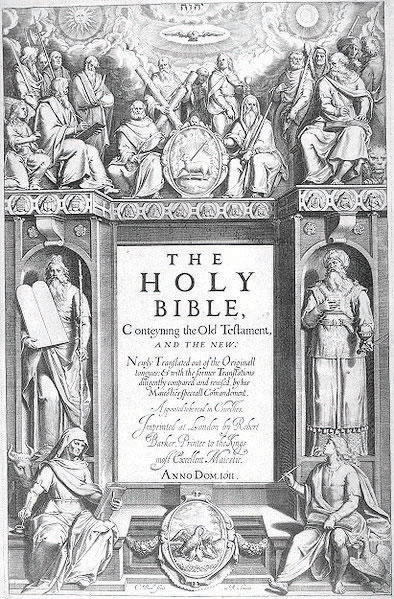

The early seventeenth century is considered the era of early modern English. Although contemporary audiences may consider the language of Shakespeare and the King James Bible quite different from 21st-century English, comparing the English of the seventeenth century with Chaucer’s Middle English reveals a vocabulary and a grammar familiar to contemporary readers. Both the works of Shakespeare and the publication of the King James Bible in 1611 helped standardize the language while at the same time enriching it with increased vocabulary and phrases now familiar to most English speakers. In her Words in English website, Suzanne Kemmer provides lists of words and phrases, now common in English, that originated with Shakespeare and the King James Bible. King James I authorized a committee of about 50 clergy/scholars to create a new English translation of the Bible, accessible to all lay people. The resulting translation was dedicated to King James I and is still commonly known by his name. The British Library presents a brief history of the King James Bible and digital images of a first edition. The Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image, University of Pennsylvania Libraries provides an interactive digital version of a 1611 King James Bible.

Title page of 1611 King James Bible.

Literature

The Metaphysical Poets

Eighteenth-century writer Samuel Johnson first used the term metaphysical poets to refer to John Donne, Andrew Marvell, and other early 17th-century poets whose poetry was characterized by elaborate, unusual metaphors and philosophical speculations. The term metaphysicalideas beyond the physical; ideas that pertain to a world beyond the natural world refers to ideas beyond the physical, to ideas that pertain to a world beyond the natural world. Metaphysical poetry often is contrasted with cavalier poetry.

The Cavalier Poets

The name cavalierliterally means knight; used to describe the followers of Charles I, the gentlemen soldiers who supported the monarchy during the English Civil War, which literally means knight, described the followers of Charles I, the gentlemen soldiers who supported the monarchy during the English Civil War. The Cavalier poets wrote light-hearted poetry that seldom had the depth of philosophical thought evident in metaphysical poetry. Often, as in the case of Herrick’s “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time,” the poetry was seduction poetry, concerned with the physical pleasures of life.

Drama and the Theatre

Although Shakespeare continued writing plays through the first decade of the 17th century and renamed his company of actors The King’s Men in honor of King James I, the early part of the 17th century is not noted for its drama. Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, and other playwrights wrote for the stage, although like Shakespeare they are often considered to belong to the Elizabethan Age. Under Puritan influence, drama and the theaters declined until in 1642 Parliament shut down the theaters completely.

Key Takeaways

- The political and religious turmoil of the 17th century influenced the literature of the era in the same way that such struggles affected Renaissance literature.

- The work of Shakespeare and the writing of the King James Bible influenced early modern English.

- Metaphysical poetry and cavalier poetry are significant movements in early 17th-century poetry.

- The Puritan government closed theatres in 1642, resulting in a dearth of English drama.

Resources

Background

- “The Case of England.” Richard Hooker. The European Enlightenment. Washington State University.

- “Citizenship 1625–1789.” The National Archives. Exhibitions. Citizenship.

- Glorious Revolution: England in the 17th Century. Harold Damerow. Union County College, Cranford, New Jersey.

- “The Gunpowder Plot.” Bruce Robinson. BBC History. BBC.

- “The Gunpowder Plot.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The Gunpowder Plot.” John H. Lienhard. Engines of Our Ingenuity. University of Houston. text and audio.

- “Gunpowder Plot CGI.” BBC History. BBC. computer generated video depicting the Gunpowder Plot.

- “History of Great Britain (from 1707).” Bamber Gascoigne. HistoryWorld.

- “Parliament in 1605.” The Gunpowder Plot: Parliament and Treason 1605. UK Parliament Website.

- “People.” The Gunpowder Plot: Parliament and Treason 1605. UK Parliament Website.

- “Rise of Parliament.” The National Archives. Exhibitions. Citizenship.

James I

- “Divine Right of Kings.” Spartacus. Schoolnet.co.uk.

- “James I of England (1566–1625).” John Butler. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “James I (1603–25).” Britannia.

Puritan Revolution

- “1642–49: Civil Wars.” Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature. Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “English Civil War.” Literary Metamorphoses. Colorado College.

- “Overview: Civil War and Revolution: 1603–1714.” Mark Stoyle. British History In-depth. BBC.

- “The Puritan Revolution.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The Puritan Revolution.” Voices for Tolerance in an Age of Persecution. Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “Puritanism in England.” David Cody and George Landow. The Victorian Web. Brown University.

Charles I

- “1649 Confessions of Charles I’s Executioner.” English Language & Literature Timeline. British Library.

- “Charles I.” The Official Website of the British Monarchy.

- “King Charles I.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium Encyclopedia Project. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol V. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 934.

- “Trial of Charles I.” The National Archives.

- “The Trial and Execution of Charles I.” History of Parliament Podcasts. http://www.parliament.uk.

- “The Execution of Charles I 1649.” EyeWitness to History.com.

Oliver Cromwell

- “Oliver Cromwell.” David Cody. The Victorian Web.

- “Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658)“ Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658).” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Interregnum

- “Interregnum (1649–1660).” The Official Website of the British Monarchy.

- “Interregnum.” Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature. Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “Interregnum (1649–60).” Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature. Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

King James Bible

- “The Holy Bible.” Furness Collection. Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

- “King James Bible.” Online Gallery: Sacred Texts. British Library.

- “King James Bible.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. British Library.

- King James Bible. Suzanne Kemmer. “A Brief History of English, with Chronology” Words in English.

- Shakespeare’s Legacy. Suzanne Kemmer. “A Brief History of English, with Chronology.” Words in English.

Metaphysical Poetry

- “Introduction.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from Herbert J.C. Grierson, ed. (1886–1960). Metaphysical Lyrics & Poems of the 17th C. 1921.

- “Metaphysical Poets.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English. Ian Ousby, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1998. 623.

Cavalier Poetry

- “Cavalier Poetry.” Jack Lynch. Glossary of Literary and Rhetorical Terms. Rutgers University.

- “The Cavalier Poets.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Robin Skelton. The Cavalier Poets. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1960. 9–10.

17th Century Drama

- “The Closing of the Theatres.” Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “The Closure of the Theaters by the Puritans.” Theater Database. rpt. from Henry Barton Baker. English Actors: From Shakespeare to Macready. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1879. 27–35.