This is “I Henry IV”, section 3.8 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.8 I Henry IV

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Categorize Shakespeare’s I Henry IV as a history play.

- Understand the actual history behind the conflicts portrayed in I Henry IV, recognize historical elements Shakespeare fictionalized, and explain the reasons for those changes.

- Trace the development of the character of Prince Hal.

- Analyze Shakespeare’s use of structure to reflect character, including the evolving character of Prince Hal.

- Identify major characters.

I Henry IV falls into the category of history plays. Elizabeth I was a direct descendent of Henry IV and Prince Hal (Henry V); therefore, the plays which glorified her ancestors were quite popular with the Queen and her court. Shakespeare apparently realized the advantages of taking dramatic liberties with historical facts, sometimes to improve the story and sometimes to please the Queen.

I Henry IV was entered in the Stationers’ Register on February 25, 1598 and published in the First Quarto in 1598. Additional printings followed frequently, attesting to the popularity of the play.

The Folger Shakespeare Library presents a brief video introduction, I Henry IV Insider’s Guide, which features actors for its production of the play discussing plot and character.

Plot

Shakespeare’s basic historical plot was likely taken from Holinshed’s Chronicles; however, Shakespeare took dramatic liberties with the timing of events. In I Henry IV, Shakespeare presents the Percies’ revolt in 1403, Archbishop Scroop’s rebellion in 1405, and Northumberland’s and the Welsh uprising in 1408 as if they occurred together in order to create a coherent plot. In another departure from historical fact, Shakespeare makes Hotspur the contemporary of Hal, thus allowing the audience to contrast the two. The historical Hotspur was closer in age to Hal’s father.

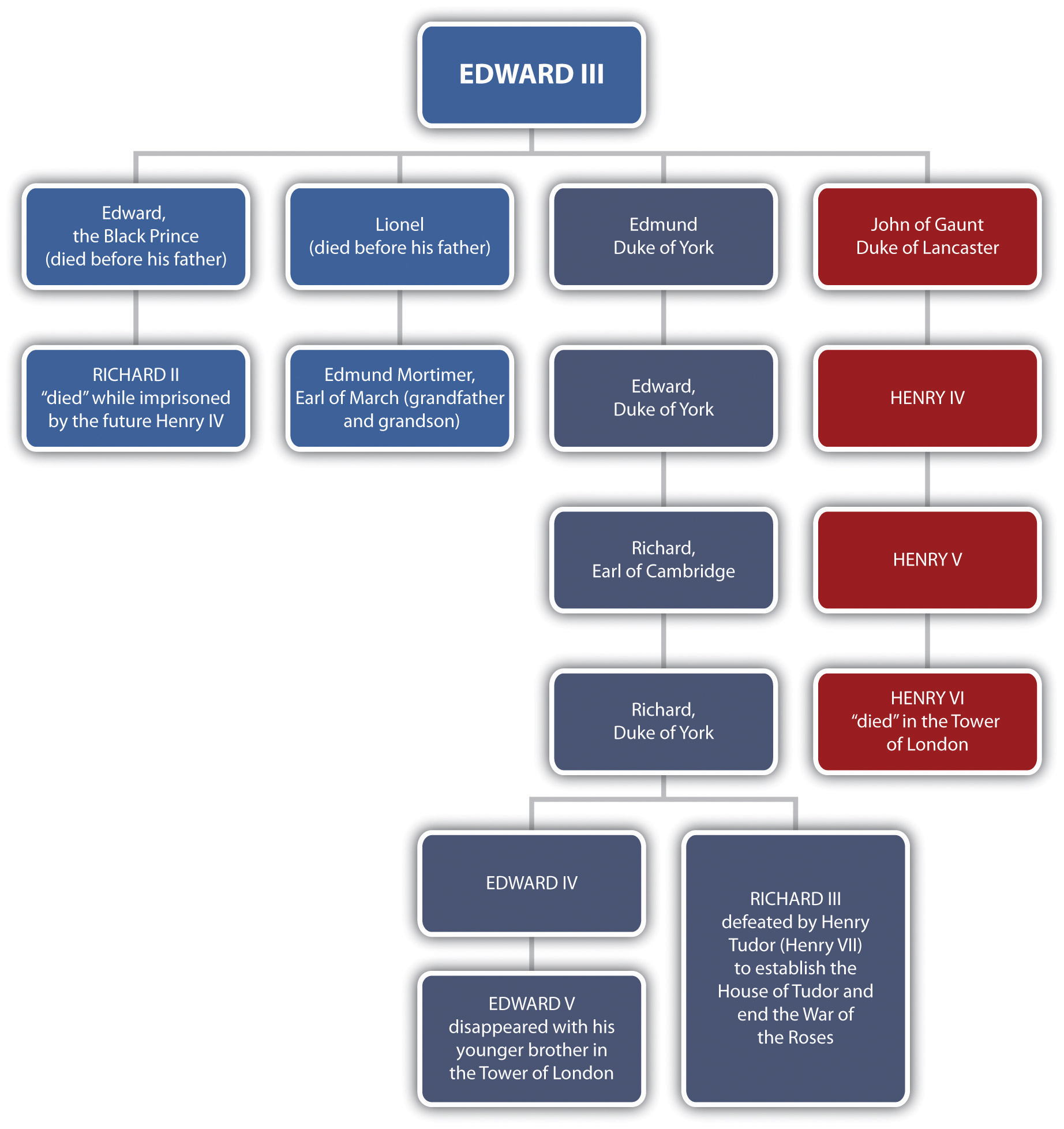

Shakespeare’s history plays Richard II, I Henry IV, II Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI Parts I, II, and III, and Richard III, present the dynastic struggles between two branches of the royal family known as the Wars of the Roses.

William Shakespeare and the Wars of the Roses

Throughout the last fifty years of the Middle Ages, England was embroiled in civil strife between two branches of the royal Plantagenet family, the Lancasters and the Yorks. Because the emblem of the Lancasters was the red rose and the emblem of the Yorks was the white rose, these battles were referred to as the Wars of the Roses. Although the Wars of the Roses are usually dated from around 1450 until 1485, the struggle stretched all the way back to the reign of Edward III which ended with his death in 1377 (during the time Chaucer was writing).

The tomb of Edward the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral.

The death of Edward III’s oldest son, known as Edward the Black Prince, resulted in conflict between supporters of Richard (Edward III’s grandson and Edward the Black Prince’s son) and supporters of his third son John of Gaunt (Chaucer’s patron) and his descendents (the house of Lancaster). Richard did become King Richard II, but died under mysterious circumstances while imprisoned by his cousin Henry who then became King Henry IV.

In the late 16th century, Shakespeare wrote a series of history plays which chronicled the Wars of the Roses:

| Edward III (attributed to Shakespeare by some scholars) | 1596 |

| Richard II | 1595 |

| Henry IV, Part 1 | 1596–1597 |

| Henry IV, Part 2 | 1597–1598 |

| Henry V | 1598–1599 |

| Henry VI, Part 1 | 1590–1591 |

| Henry VI, Part 2 | 1590–1591 |

| Henry VI, Part 3 | 1591–1592 |

| Richard III | 1592–1593 |

Edward III

Edward III was a politically and militarily strong king who had 4 sons, all of whom had the strong personality and leadership abilities of their father. Had the oldest son, Edward the Black Prince, lived, the Wars of the Roses might never have taken place; the throne would without question have passed to Edward. Edward the Black Prince, however, died before his father, leaving his 10-year-old son Richard as his heir.

During the 14th century, a king still had to be a warrior to hold on to his throne; an important part of a king’s job was holding territory against invaders. A boy-king was dependent on his “protectors” to fight his battles for him and to ward off usurpers until he could physically protect himself and his domain.

When King Edward III died, many people felt that the crown should pass not to his 10-year-old grandson Richard, but to one of his other sons, John Duke of Lancaster (red rose) or Edmund Duke of York (white rose). John and Edmund agreed! (Lionel, the second son, had also died, but his descendents were the Nevilles, who by marriage figured prominently in the future royal line.)

The battle for the crown had begun.

Richard II

The grandson Richard was crowned but proved to be a weak, unpopular king. His cousin Henry, son of John Duke of Lancaster, felt that he would be a much better king and that his father really should have been king anyway. Henry staged a rebellion against Richard, captured him, and Richard soon “died” in prison. Henry declared himself King Henry IV.

Henry IV

Henry IV was a strong king who put down 4 separate rebellions led by people who had supported Richard II.

Henry V

Henry V was one of the best of English kings. He recaptured parts of France and sealed the bargain by marrying Katherine, daughter of the French king. England probably could have peacefully united behind Henry V, ending the dynastic conflict. Unfortunately, Henry V died, leaving his infant son Henry as his heir.

Henry VI

Henry VI grew up to be a weak leader, a scholarly, religious man who really wanted to be a priest, not a king. He ignored affairs of state in favor of solitary study and worship. He lost all the lands in France won by his father, and his cousin, Richard Duke of York, soon started a military campaign to overthrow the Lancastrian King Henry VI. Richard and one of his sons were captured and executed by Henry’s armies, their heads posted on stakes over Micklegate Bar in the city of York. The surviving sons Edward, George, and Richard continued their father’s battle with the substantial help of another cousin, Richard Neville (known as Warwick the Kingmaker). Henry VI’s troops were defeated, and he was imprisoned in the Tower of London where he “died” during Edward’s reign.

Edward IV

With Henry VI in prison, Edward was crowned King Edward IV. He was a young, tall, handsome man with strong military and political skills, and the English people generally welcomed his leadership. Since Henry VI’s only son Edmund (son of Margaret and husband of Anne Neville in Richard III) had been killed in battle, he had the strongest claim to the throne. Both his mother and his father were descendents of Edward III. But again, the death of the father before his sons were of age plunged the country into another war of the red rose of Lancaster and white rose of York. Before he died, Edward IV named his younger brother Richard “protector” of his heir.

Edward V

The 12-year-old son of Edward IV was never officially crowned but is referred to as Edward V. His uncle Richard had him taken to the Tower of London for security reasons, and young Edward V was never seen again. No one knows when or how he and his younger brother Richard died.

Richard III

With all the Lancastrian claimants to the throne dead and all his older Yorkist brothers dead as well, Richard became king. He was soon challenged, however, by Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. Henry Tudor had the weakest of claims to the throne. He was a descendent of John of Gaunt and his second wife (who had first been his mistress) and of the wife of Henry V and her second husband, Owen Tudor, a Welsh commoner.

Henry VII

Henry Tudor defeated Richard III in battle at Bosworth Field and was crowned King Henry VII. He married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV. With his Lancastrian blood and her Yorkist blood, their descendents thus united the two warring factions of the family and established the Tudor dynasty. Their son Henry VIII and his daughter Elizabeth I were two of England’s strongest monarchs.

“The rose both white and rede

In one rose now doth growe”

The Wars of the Roses.

Structure and Theme

Shakespeare’s use of a comic element, the character Falstaff and the subplot involving his exploits, as a central feature of the play is an important development in the history play as a dramatic form. Falstaff is a miles gloriosusthe braggart solider, a stock character in classical Roman comedy—the braggart solider, a stock character in classical Roman comedy—and is often considered Shakespeare’s greatest comic character.

Statue of Falstaff in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Statue of Prince Hal in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Notice how the scenes in the play alternate between the court and the tavern, from the serious affairs of state to the practical jokes of the barroom. Also notice the alternating forms of the speeches. The regal, honorable characters’ lines are written in verse; Falstaff and the tavern gang speak in prose, indicating their low status. Prince Hal is caught in the middle; he vacillates between his role as the royal prince and his role as an irresponsible jokester. The alternating tavern scenes and political-military scenes correspond with Hal the rogue and Hal the Prince. They also provide contrast between Hal and Hotspur (responsibility) and Hal and Falstaff (revelry). One of the major themes of the play is Hal’s preparation to become king—his growing up.

Characters

The King’s Entourage

- King Henry IV—reigning monarch (house of Lancaster); became king by overthrowing and killing his cousin Richard II; Bullingbrook (sometimes called Henry Bullingbrook or Bolingbroke because he was born in the town of Bolingbroke)

- Prince Hal—Henry, Prince of Wales; King Henry IV’s oldest, wayward son and heir to the throne; sometimes called Henry Monmouth because Monmouth was his birthplace)

- Prince John of Lancaster—King Henry IV’s younger son

- Earl of Westmoreland—King Henry’s “gentle cousin”

- Sir Walter Blunt—King Henry’s “dear, true, industrious friend”

The Percy Party

- Henry Percy—Earl of Northumberland; Hotspur’s father

- Thomas Percy—Earl of Worcester; Hotspur’s uncle

- Hotspur (Henry) Percy—son of Northumberland; Prince Hal’s contemporary; held up by Henry IV as an example to Prince Hal

- Edmund Mortimer—Earl of March; Richard II’s legal heir to the throne

- Archibald—Earl of Douglas; Scottish ally

- Owen Glendower—Welsh magician

- Sir Richard Vernon

- Richard Scroop—Archbishop of York

- Sir Michael—a friend of the Archbishop

- Lady Percy—Hotspur’s wife and Mortimer’s sister

- Lady Mortimer—Glendower’s daughter and Mortimer’s wife; speaks only Welsh

Prince Hal’s Tavern Gang

- Sir John Falstaff—the miles gloriosus; one of Shakespeare’s most famous characters

- Poins, Gadshill, Peto, Bardolph—friends of Falstaff and members of the tavern gang

- Mistress Quickly—hostess of the tavern frequented by Falstaff

Key Takeaways

- I Henry IV is based on historical events but has some deviation from actual history

- Falstaff, the miles gloriosus, is one of Shakespeare’s most famous comic characters

- The structure of the play’s lines echoes the theme of Prince Hal’s evolving character.

Exercises

- At the beginning of the play, our opinion of Hotspur is quite high. He is described by King Henry IV as “the theme of honor’s tongue.” What are some of the details that establish this picture of Hotspur as the essence of honor and nobility?

- As the play progresses, our picture of Hotspur begins to deteriorate. What are some of the details that gradually let us see Hotspur’s less-than-admirable qualities?

- At the end of Act I, scene 2 is Hal’s famous soliloquy, a speech delivered when a character is alone on stage, used for the purpose of revealing the character’s thoughts or feelings. Explain Hal’s comparison of himself to the sun. Compare this reference to the sun with two others in the play: Act IV, scene 1, lines 94–102 and Act V, scene 1, lines 1–2.

- In Act I, scene 2, Hal speaks in prose when he’s talking with Falstaff and the others at the tavern, but in his soliloquy his speech is in verse. What does the change in form of Hal’s speech suggest about Hal’s character?

- In Act II, while his father and his younger brother are planning battles to preserve the throne and state, what is Hal planning? How do these plans contribute to our estimation of Hal?

- In Act III, Hal finally must confront his father King Henry IV. The king makes a typical fatherly “when I was your age” speech to his son. How does Hal vow to redeem himself in his father’s eyes?

- Does Hal prove himself worthy to be the heir to the throne? How?