This is “Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593)”, section 3.4 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.4 Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize characteristics of Senecan tragedy used in Marlowe’s drama.

- Apply the definition of the pastoral mode to Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.”

Biography

Christopher Marlowe is a good example of an individual caught up in the intrigue and danger of court life who might long to escape to the seemingly simple, leisurely life of the rustic shepherd. Although not born into the nobility, Marlowe attended Cambridge University, then moved to London where he moved in court circles and wrote the plays that secured his fame. He also apparently was engaged in espionage for Elizabeth’s court. At age 29 Marlowe was stabbed to death in an argument over the dinner bill in an inn. Only a week before his death, one of his associates and fellow dramatist, Thomas Kyd, claimed under torture that Marlowe was an atheist, and a warrant was issued for Marlowe’s arrest. This sequence of events has led some historians to believe that Marlowe’s death was staged to help him escape arrest and certain torture. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that Marlowe, in hiding, wrote the plays attributed to Shakespeare although this theory is now considered unlikely.

Portrait believed to be Christopher Marlowe.

Plaque marking the rooms where Christopher Marlowe lived at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University.

Marlowe’s Plays

The Tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part I

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

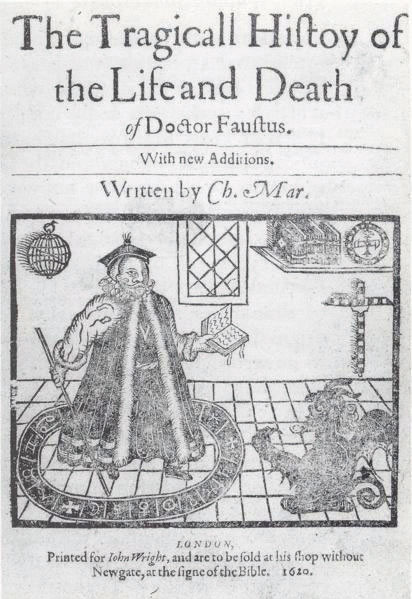

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

Title page of a late edition of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.

- A Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- B Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Jew of Malta

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries. The Horace Howard Furness Shakespeare Library.

The Tragedy of Edward II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

The Massacre at Paris

Marlowe’s contemporary and fellow playwright and poet Ben Jonson, in his poem “To the Memory of My Beloved Master William Shakespeare,” coined the phrase “Marlowe’s mighty line” to refer to Marlowe’s use of blank verseunrhymed lines of iambic pentameter, often considered the meter most closely resembling normal English speech, unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter, considered the meter most closely resembling normal English speech. The sonorous lines of blank verse lent themselves to the tragic content of plays such as Tamburlaine and The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus.

In the Renaissance spirit of celebrating and imitating classical art and literature, Marlowe wrote heroic tales in the tradition of the classical Roman dramatist Seneca. Senecan tragedydrama featuring violence, revenge, emotional speeches, and supernatural, usually dark supernatural, elements featured violence, revenge, emotional speeches, and supernatural, usually dark supernatural, elements. Marlowe’s tragedies portray men with aspiring spirits who rise to greatness and then fall, usually through some weakness or flaw in the hero’s own character. Perhaps his most famous character, Dr. Faustus deals with the demon Mephistopheles to sell his soul to the devil to achieve his ambition of power through knowledge only to disappear, presumably to Hell, at the end of the play.

“The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”

Text

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Sidebar 3.1.

Come live with me and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That hills and vallies, dales and fields,

Woods or steepy mountain yields.

And we will sit upon the rocks,

Seeing the shepherds feed their flocks

By shallow rivers to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of roses

And a thousand fragrant posies,

A cup of flowers and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of myrtle.

A gown made of the finest wool

Which from our pretty lambs we pull;

Fair-linèd slippers for the cold,

With buckles of the purest gold.

A belt of straw and ivy-buds,

With coral clasps and amber studs;

An if these pleasures may thee move,

Come live with me, and be my love.

The shepherd-swains shall dance and sing

For thy delight each May-morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me, and be my love.

Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” is one of the most well-known examples of pastoral poetry, a type of literature that portrays shepherds in an idealized rural setting, engaging in contests of singing or poetry, flirting with country maidens, watching their flocks in a peaceful and beautiful natural world. Most of the people who wrote pastoral poetry were, however, men of the court who had only a “fairy tale” view of a shepherd’s life. They imagined shepherds sitting in the meadows watching their sheep while singing songs and flirting with the shepherdesses. They had little idea of the hard lives led by the peasants. Marlowe’s reference to “pulling” the wool off the sheep, for example, demonstrates that he had little real knowledge of sheep herding, and his mistaken belief that a shepherd would have gold for his lady’s buckles indicates that his life was far removed from that of a poor shepherd.

Exercises

- In Marlowe’s poem, what does the shepherd offer to entice his love to live with him?

- How do these enticements fit into the pastoral convention?

Resources

Biography

- “Christopher Marlowe.” Theatre History.com. rpt. from Elizabethan and Stuart Plays. Ed. Charles Read Baskerville. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1934. 307–308.

- “Christopher Marlowe’s Canterbury Childhood.” Theatre History.com. rpt. from Christopher Marlowe and His Associates. John H. Ingram. London: Grant Richards, 1904.

- “The Life and Work of Christopher Marlowe.” Theatre History.com. rpt. from Christopher Marlowe. William Lyon Phelps. New York: American Book Company, 1912.

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol XVII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 744.

- “Marlowe Timeline.” OpenLearn. The Open University.

Play Texts

The Tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part I

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

- A Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- B Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Jew of Malta

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries. The Horace Howard Furness Shakespeare Library.

The Tragedy of Edward II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

The Massacre at Paris

Text “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen.

- Project Gutenberg.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

- “Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus.” Dr Anita Pacheco. Learning Space. The Open University. course materials from The Open University course.

Audio

- “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Eaglesweb.com. Audio Anthology of Lyrical Poetry in Modern English. Recorded by Walter Rufus Eagles.

Selections from Librivox

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Doctor Faustus (closing lines)” (in “Poems Recorded in Deptford and Greenwich”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Hero and Leander.”

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Jew of Malta, The.”

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to His Love” (in “Short Poetry Collection 061”) Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to his Love, The” (in “Wedding Poems”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to His Love, The” (in “Romantic Poetry Collection 001”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to His Love, The” (in “Short Poetry Collection 088”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, The.”