This is “The Sixteenth Century”, section 3.1 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

3.1 The Sixteenth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the atmosphere of energy and turbulence in the political and religious realms that influenced 16th-century literature, including the ideas of the Renaissance and the Reformation.

- Define the types of literature typical of the 16th century including the sonnet, pastoral poetry, and drama.

- Understand the development of purpose-built theaters and how this development influenced 16th-century drama.

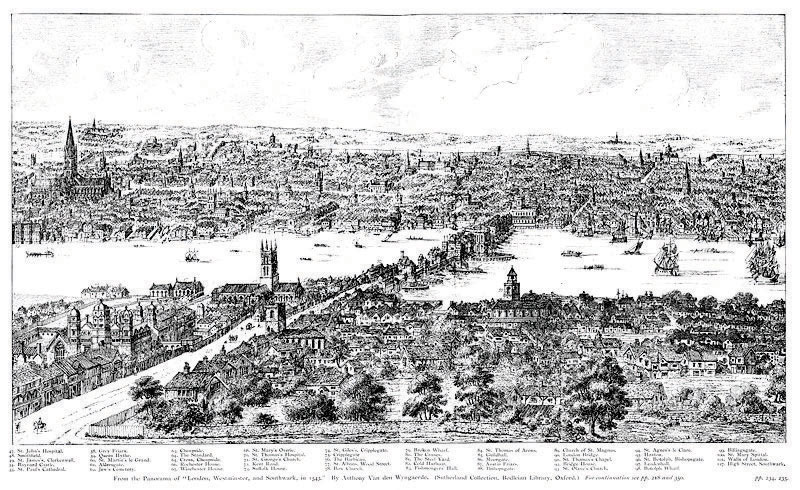

Wyngaerde’s “Panorama of London in 1543.”

Brash, exciting, bustling, expanding, prosperous, dangerous, precarious—all these words describe sixteenth-century England. As a nation, England was sure of herself and her dominance of the seas and the exploration for which names such as Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Francis Drake became famous. London, which began to thrive with the emerging middle class during the Middle Ages, grew overcrowded and, like the River Thames that flowed through her center, congested with all the flotsam and jetsam of a thriving metropolis. The city incorporated great wealth and beauty next to squalor and wretched poverty. Business and commerce flourished on the river and in the city, but so did crime and disease.

The Tudor Court

The Tudor court echoed all the qualities of the city of London, including the danger and intrigue.

The Tudor Rose—the emblem of the Tudor rulers, symbolizing the unification of the white rose of the Yorks and the red rose of the Lancasters.

Throughout the last fifty years of the Middle Ages, England was embroiled in civil strife between two branches of the royal Plantagenet family, the Lancasters and the Yorks. Because the emblem of the Lancasters was the red rose and the emblem of the Yorks was the white rose, these battles were referred to as the Wars of the Roses. When Henry Tudor (of the house of Lancaster) defeated Richard III (of the House of York) in 1485, he established the Tudor rulers that provided one of the most powerful yet turbulent dynasties to reign in Britain.

Henry VII

Henry Tudor, King Henry VII, married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Yorkist King Edward IV. Their marriage united the two warring factions of the royal family, bringing an end to the Wars of the Roses. Their son Henry became one of England’s most notorious monarchs, King Henry VIII.

Henry VIII

“The Rose both White and Red

In one Rose now doth grow”

John Skelton

King Henry VIII succeeded to the throne in 1509 ending the Wars of the Roses that had torn England asunder for years, bringing unity to a war-weary country. Unfortunately, Henry VIII soon had the country embroiled in new struggles. Large in physical stature and in character, Henry VIII ruled with an iron hand. He is perhaps remembered most for his six wives. Henry was a second born son; his older brother and the heir apparent Arthur died shortly after he was married to Catherine of Aragon to establish an alliance with Spain. Henry VIII married his brother’s widow, again for dynastic reasons. Years passed, however, without a male heir from their union. Catherine did give birth to a daughter Mary, but Henry felt the need for a male heir to ensure the continuance of the Tudor line.

Henry’s desire to divorce Catherine led to the Reformationthe movement to reform the Roman Catholic Church which led to the establishment of Protestant denominations, the movement to reform the Roman Catholic Church which led to the establishment of Protestant denominations, in England. Although the Reformation, led by Martin Luther, was well under way on the European continent, Henry VIII’s break from the Roman Catholic Church was to suit his own purposes, not a result of his religious convictions. When the Roman Catholic Church refused to grant Henry’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, Henry declared himself the head of the Church in England, essentially breaking away from the Roman Church and the Pope’s authority and establishing what is now the Anglican Church, the Church of England. With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Henry VIII became the head of both Church and State. The Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, appointed by Henry, nullified Henry’s marriage to Catherine, allowing him to marry Anne Boleyn, who gave birth to a daughter Elizabeth. When Anne, too, failed to provide a male heir, Henry had her beheaded based on charges of adultery and incest, accusations many historians believe to be false. He soon married Jane Seymour, who finally gave Henry his long-awaited male heir, Edward.

Edward VI

Upon Henry VIII’s death in 1547, his nine-year-old son became King Edward VI. Because of his age and frail health, a bevy of relatives and advisors attempted to control the throne through the young king. He died at age 15, after attempting to exclude his sisters from ascending to the throne.

Mary I

Henry VIII’s older daughter Mary I was, like her mother Catherine of Aragon, devoutly Roman Catholic. Her accession to the throne brought about a return to the Roman Catholic Church as the official church in England. Just as her father Henry VIII had persecuted those who refused to renounce their Catholic faith and acknowledge him rather than the Pope as head of the Church, Mary I persecuted those who resisted the return to the Roman Catholic faith. Possibly as many as three hundred people were burned at the stake as heretics under her rule, earning her the nickname Bloody Mary. One of those burned at the stake was Archbishop Cranmer who had granted her father’s divorce from her mother.

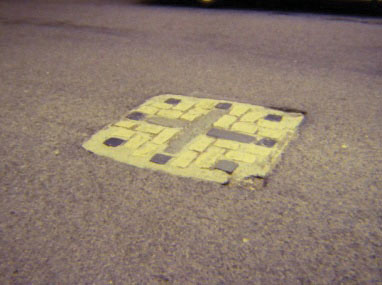

This cross in Broad Street in the city of Oxford marks the place where three bishops, Ridley, Latimer, and Cranmer, were burned at the stake on the orders of Mary I.

Elizabeth I

When Mary I died in 1558, the last surviving child of Henry VIII became Queen Elizabeth I and led England into a time of prosperity, predominance in world power, and relative religious peace at home. Although she restored the Protestant Church of England her father had established, she was more tolerant in her religious governing than either her father or her sister Bloody Mary had been. The defeat of the Spanish Armada established England as a dominant naval power, and English explorers established colonies that set the stage for the British Empire of the 19th century. Her reign is considered a Golden Age for England, an era often referred to as the Elizabethan Age.

The English Renaissance

The word renaissanceliterally means “re-birth”; generally used to refer to a renewed interest in classical learning and a desire to seek new knowledge literally means “re-birth” and is generally used to refer to a renewed interest in classical learning and a desire to seek new knowledge. Beginning in Italy in the early 14th century, the Renaissance (a term not used until modern times) spread to Britain in the 16th century. The English Renaissance provided fertile ground for literature. Renaissance ideas included an emphasis on education that led to increased literacy and an emphasis on form and order that affected the types of literature produced in 16th-century Britain.

Literature

The architectural style of Elizabethan stately homes reveals a penchant for symmetry and order. To honor Henry VIII or Elizabeth I, great houses were sometimes built in the shape of the letters H or E. The knot garden and topiary also became popular ornamentation on great estates.

Figure 3.1

In Figure 3.1., the contemporary garden at Broughton Castle, is a knot garden, a garden with clearly defined lines and boundaries forming geometric shapes.

Figure 3.2

In Figure 3.2., this contemporary garden is at Hampton Court Palace, originally the home of Henry VIII’s advisor Cardinal Wolsey, and then, at Henry’s suggestion, the home of the King and his second queen, Anne Boleyn. Note the flowers planted in colorful but orderly straight rows and the bushes trimmed to geometrical shapes.

Figure 3.3

As seen in Figure 3.3., at Hampton Court Palace, even the trees were trimmed into artificial shapes.

This preference for symmetry and order is seen not only in Elizabethan houses and gardens, but also in the literature of the 16th century. Reflecting a belief that art was nature improved by human enhancement, the literature of the period often used structured forms and styles such as the sonnet and the Spenserian stanza.

The Sonnet

In an age which valued highly structured poetry, the sonneta poem of 14 lines and a set rhyme scheme, a poem of 14 lines and a set rhyme scheme, was one of the most popular forms. The Sonnet Central Time Line illustrates the concentration of sonnets written during the 16th and early 17th century, as well as a later renewed interest in sonnets during the 19th century.

PowerPoint 3.1.

Follow-along file: PowerPoint title and URL to come.

The Pastoral Mode

In the Elizabethan courtier’s world of political maneuvering for status with the monarch, intrigue and betrayal by others also striving for power, it’s not surprising that the classical idea of otium, a peaceful leisure filled with art and nature, appealed to courtier/writers.

Derived from the Latin root word pastor, meaning shepherd, the pastoral modea type of literature that portrays shepherds in an idealized rural setting, engaging in contests of singing or poetry, flirting with country maidens, watching their flocks in a peaceful and beautiful natural world is a type of literature that portrays shepherds in an idealized rural setting, engaging in contests of singing or poetry, flirting with country maidens, watching their flocks in a peaceful and beautiful natural world. Although this idealized, fairy-tale world bore little resemblance to the lives of peasants who actually attempted to make a living raising sheep, the pastoral mode charmed the courtier whose life and fortune depended not just on his skills in battle but also on the vagaries of the monarch.

Drama

In 1576, James Burbage built the first theater in London, aptly named The Theatre. Before dedicated theaters were built, plays were often performed in the yards of coaching inns, open cobblestone areas where coaches stopped for passengers to eat, rest, or stay overnight at the inn. Many inns had galleries, covered walkways or balconies on the second floor leading to rooms that could be rented. When a play was performed, the audience could stand in the yard or pay extra to stand on one of the galleries for a better view. This basic layout was followed in the design of Elizabethan theatres.

The George Inn, the only remaining galleried inn in London.

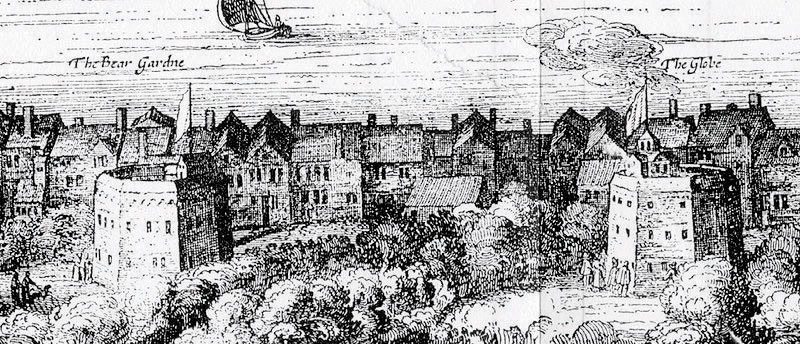

A few drawings from the 16th century provide information about how 16th-century theatres, including the Rose, were designed. Internet Shakespeare Editions from the University of Victoria provides an interactive look at a 16th century stage, and the Folger Shakespeare Library explains the origins and the workings of the theatres familiar to Shakespeare.

Replica of the Globe in London.

Although not the first of Elizabethan theatres, the Globe is the most well-known and the most closely associated with Shakespeare.

Wesleyan University provides a 3-D model of the Globe Theatre and an animation of how the parts of the stage might have been used in the graveyard scene from Hamlet. Clemson University provides a virtual tour of the Globe Theatre as it likely appeared in Shakespeare’s time. Shakespeare’s Globe in London, a replica of the original Globe theatre, offers a virtual tour of this contemporary active theatre. Although designed for children, Cambridge University’s Converse program presents an entertaining and informative interactive animation depicting the 16th-century play-going experience.

Nicholas Visscher’s map of the City of London (1616), showing the Globe Theatre.

The “University Wits”

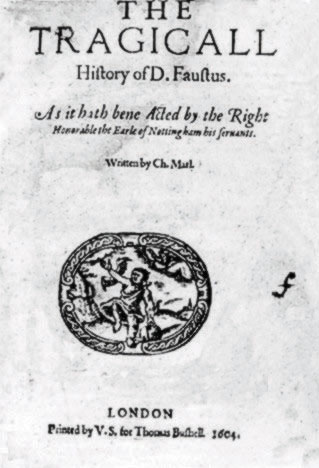

While Shakespeare’s name dominates English Renaissance drama, he was not the only, or even the first, dramatist of the era. Preceding Shakespeare was a group of playwrights known as the “University Wits.” Perhaps the best known of the University Wits, Christopher Marlowe developed what Ben Jonson called “Marlowe’s mighty line,” the sonorous use of blank verse also employed by Shakespeare.

Shakespearean drama represents a high point unequaled in literature. On the heels of the flowering of Elizabethan drama, the Puritans shut down the theatres in England. Thus, a dearth of drama quickly followed the wealth of Shakespeare’s time period.

Key Takeaways

- The 16th century was a highlight in British history, resulting in literature that reflected the vitality but also the turbulence of the period.

- Highly structured forms of literature such as the sonnet, the Spenserian stanza, and the blank verse of Marlowe’s and Shakespeare’s drama reflected the Renaissance’s interest in classical literature.

- Literature written in the pastoral mode reflected a desire for a simple, peaceful existence away from the intrigue of court life.

- The 16th century saw the development of purpose-built theaters.

Resources

Background

- “City Life.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “The City of London.” Life in Elizabethan London. A Compendium of Common Knowledge.

- “Elizabethan England.” Shakespeare Resource Center.

- “London Bridge Virtual Tour.” British History In-Depth. BBC.

- “Sir Francis Drake.” Historic Figures. BBC.

The Tudor Court

- Anne Boleyn. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Catherine of Aragon.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Court Politics.” History of England. Britain Express.

- “Edward VI.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Elizabeth.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Elizabeth I: An Overview.” Alexandra Briscoe. BBC. British History In-Depth.

- “Elizabeth of York.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Elizabethan Life.” History of England. Britain Express.

- “Henry VIII and the Break with Rome.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Jane Seymour.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “King Henry VIII.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Queen Mary I.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “The Act of Supremacy.” National Archives.

- “The Reformation.” E. L. Skip Knox. Boise State University.

- “The Six Wives of Henry VIII.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “The Spanish Armada.” Simon Adams. BBC. British History In-Depth.

- “The Wars of the Roses.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “The Wars of the Roses.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The English Renaissance

- “Education.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Putting Nature in Order.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “A Rebirth of Knowledge.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- “Renaissance.” English Department. Brooklyn College.

- “Syrup of Violet.” Folger Shakespeare Library. Women’s contributions to science in the Renaissance.

Literature

- “The Spenserian Stanza.” Department of English. Emory University.

The Sonnet

The Pastoral Mode

- “Court Life: Hoping for Reward.” Museum of London.

- “Pastoral.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English University of Victoria.

- “Queen Elizabeth: Courtship and Love.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The Queen’s Court.” National Maritime Museum.

Drama

- “Blank Verse.” The Poetry Archive.

- “Christopher Marlowe.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “The Elizabethan Theatre.” Hilda D. Spear. University of Dundee. University of Cologne.

- The George Inn video. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- Globe Theatre video. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “Globe Tour.” Clemson Shakespeare Festival. Clemson University.

- “How Do We Know About Shakespeare’s Stage?” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “James Burbage.” Theatredatabase. rpt. from A Dictionary of the Drama. W. Davenport Adams. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1904.

- “The Parts of the Stage.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Playhouses.” Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library.

- “The Plays of the University Wits.” Bartleby.com. Rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume V. The Drama to 1642, Part One.

- “The Rose.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Shakespeare’s Globe Theater.” Learning Objects Program. Wesleyan University.

- “Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre.” Virtual Tour. Converse: The Literature Website. University of Cambridge.

- “Shakespeare’s Theater.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The University Wits.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Virtual Tour.” Shakespeare’s Globe. The Shakespeare Globe Trust.