This is “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”, section 2.4 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.4 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify literary techniques used in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Identify and account for the pagan and Christian elements in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Define medieval romance and apply the definition of the genre to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

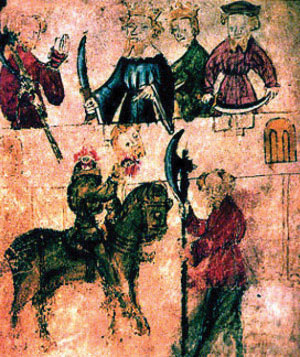

Beheading of the Green Knight.

From the manuscript Cotton Nero A.x, f. 94b

The last 40 years of the Middle Ages, from 1360 to 1400, produced the three greatest works of medieval literature:

- Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales

- Malory’s Morte d’Arthur

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by the Pearl Poetthe unidentified author of Pearl, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the unidentified author of Pearl, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Scholars believe the same unknown individual wrote Pearl, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, thus referring to him as the Pearl poet.

Text

Modern English Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Verse translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. University of Rochester. The Camelot Project. Prose translation. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/sggk.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Paul Deane. Forgotten Ground Regained: A Treasury of Alliterative and Accentual Poetry. Verse translation. http://alliteration.net/Pearl.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. A. Neilson. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Prose translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/sggk_neilson.pdf

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Close Verse Translation. Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/ready.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Middle English Arthurian Romance Retold in Modern Prose. Jessie L. Weston. Google Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=j8l7-HnlMfkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=sir+gawain+and+the+green+knight&source=bl&ots=C7I7E8GMVE&sig=cvMDxdXVp1PqOueBlJSEZPjXhpE&hl=en&ei=x2twTMmFKoL7lweM6smADg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=13&ved=0CFsQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&

Original Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Dr.Murray McGillivray, University of Calgary, Team Leader. University of Calgary. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/transnew.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;rgn=main;view=text;idno=Gawain

Audio

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. H. Neilson. LibriVox. Recording in modern English. http://www.archive.org/details/gawain_mj_librivox

Alliterative Revival

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is part of a movement known as the alliterative revivala resurgent use of the alliterative verse form of oral Old English poetry such as Beowulf, a resurgent use of the alliterative verse form of oral Old English poetry such as Beowulf. In the following lines, the first two lines of the poem, note the repetition of the s sounds in line 1 and in line 2 the b sounds:

Sidebar 2.1.

SiÞen Þe sege and Þe assaut watz sesed at Troye,

Þe borʒ brittened and brent to brondeʒ and askez

Sidebar 2.2.

Since the siege and the assault was ceased at Troy,

The burg [city] broken and burned to brands [cinders] and ashes

Bob and Wheel

As these first two lines of the poem illustrate, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is written in long alliterative lines, each stanza having a varying number of lines. These long alliterative lines are followed by the bob and wheela group of five short lines at the end of an alliterative verse rhyming ABABA, a group of five short lines at the end of an alliterative verse rhyming ABABA.

For example, in stanza three, beginning with line 37, the story begins with a description of King Arthur and his court at Camelot in eighteen long alliterative lines followed by the five short lines of the bob and wheel:

Sidebar 2.3.

on sille

Þe hapnest under heuen

kyng hyʒest mon of wylle

hit werere now gret nye to neuen

so hardy ahere on hille

Sidebar 2.4.

in the hall

the most fortunate ones under heaven

highest king of most will

it is now hard to name

so hardy a one on the hill

Notice the two-syllable line called the bob and the four lines called the wheel:

Sidebar 2.5.

on sille

Þe hapnest under heuen

kyng hyʒest mon of wylle

hit werere now gret nye to neuen

so hardy ahere on hille

Also notice the ABABA rhyme scheme:

Sidebar 2.6.

| on sille | A |

| Þe hapnest under heuen | B |

| kyng hyʒest mon of wylle | A |

| hit werere now gret nye to neuen | B |

| so hardy ahere on hille | A |

Green Man Myth

Also like Old English poetry, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, although composed well into the Middle Ages when the Church dominated society, combines hints of paganism in the figure of the Green Knight with obvious Christian elements in Sir Gawain. The Green Knight is a type of Green Mana character in ancient fertility myths representing spring and the renewal of life, a character in ancient fertility myths representing spring and the renewal of life, a parallel of Christian belief in resurrection. In some decapitation myths, a motif found in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the blood of the Green Man symbolizes the fertilizing of crops, thus insuring an adequate food supply. Surprisingly, Green Man symbols are common in Gothic cathedrals, such as these in Ely Cathedral, in York Minster, and in the ruins of Fountains Abbey.

Green Man in Ely Cathedral.

Green Man in York Minster.

Green Man in the ruins of Fountains Abbey.

Chivalry and Courtly Love

In this story, the actions of Sir Gawain and the rest of King Arthur’s knights are measured by chivalry, the code of conduct which bound and defined a knight’s behavior. In fact, the ordeal that Sir Gawain endures is eventually revealed to be a test of the Court’s dedication to their vows of knighthood.

The concept of medieval chivalry was famously described in 1891 by Leon Gautier, who listed ten rules of chivalry from the 11th and 12th centuries:

- Thou shalt believe all that the Church teaches and shalt observe all its directions.

- Thou shalt defend the Church.

- Thou shalt respect all weaknesses and shalt constitute thyself the defender of them.

- Thou shalt love the country in the which thou wast born.

- Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy.

- Thou shalt make war against the infidel without cessation, and without mercy.

- Thou shalt perform scrupulously thy feudal duties, if they be not contrary to the laws of God.

- Thou shalt never lie, and shalt remain faithful to thy pledged word.

- Thou shalt be generous, and give largesse to everyone.

- Thou shalt be everywhere and always the champion of the Right and the Good against Injustice and Evil.

In addition to the ideals of chivalry, the nobility often modeled their behavior, in literature at least, on the concept of courtly loverules governing the behavior of knights and ladies in a ritualistic, formalized system of flirtation, rules governing the behavior of knights and ladies in a ritualistic, formalized system of flirtation. Courtly love is an integral part of the medieval romances sung by troubadours as entertainment in the courts of France, stories of knights inspired to great deeds by their love for fair damsels, sometimes a damsel in distress rescued by the knight. The idea behind amour courtois is that a knight idealized a lady, a lady not his wife and often in fact married to another, and performed deeds of chivalry to honor her.

“Rules” governing the conduct of a knight involved in courtly love were outlined by Andreas Capellanus in his 12th-century book The Art of Courtly Love. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies lists Capellanus’ rules:

- Marriage is no real excuse for not loving.

- He who is not jealous cannot love.

- No one can be bound by a double love.

- It is well known that love is always increasing or decreasing.

- That which a lover takes against his will of his beloved has no relish.

- Boys do not love until they arrive at the age of maturity.

- When one lover dies, a widowhood of two years is required of the survivor.

- No one should be deprived of love without the very best of reasons.

- No one can love unless he is impelled by the persuasion of love.

- Love is always a stranger in the home of avarice.

- It is not proper to love any woman whom one should be ashamed to seek to marry.

- A true lover does not desire to embrace in love anyone except his beloved.

- When made public love rarely endures.

- The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

- Every lover regularly turns pale in the presence of his beloved.

- When a lover suddenly catches sight of his beloved his heart palpitates.

- A new love puts to flight an old one.

- Good character alone makes any man worthy of love.

- If love diminishes, it quickly fails and rarely revives.

- A man in love is always apprehensive.

- Real jealousy always increases the feeling of love.

- Jealousy, and therefore love, are increased when one suspects his beloved.

- He whom the thought of love vexes, eats and sleeps very little.

- Every act of a lover ends with the thought of his beloved.

- A true lover considers nothing good except what he thinks will please his beloved.

- Love can deny nothing to love.

- A lover can never have enough of the solaces of his beloved.

- A slight presumption causes a lover to suspect his beloved.

- A man who is vexed by too much passion usually does not love.

- A true lover is constantly and without intermission possessed by the thought of his beloved.

- Nothing forbids one woman being loved by two men or one man by two women.

Note that many of the stereotypical signs of being in love are listed, such as appearing pale (#15), being unable to eat or sleep (#23), and displaying jealousy (#21). Other familiar concepts such as playing hard to get (#14) and secret loves (#13) come from the rules of courtly love. The rules also make clear that engaging in the rituals of courtly love is only for the nobility (#11).

The concept of courtly love and the medieval romance arrived in Britain with Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, a region in what is now France, and her marriage to the English King Henry II.

Images from the Middle Ages portray noble couples in typical aristocratic medieval activities: playing chess, hunting with falcons, dancing, and, in some images, obviously engaging in courtly flirtations. In one scene, for example, a lady appears to be presenting a token to a knight. In another, a knight appears to have stabbed himself, possibly in despair over his unrequited love. In another scene, knights fight in a tournament while adoring ladies watch from the stands.

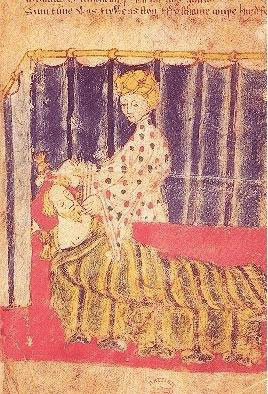

Temptation of Sir Gawain by Lady Bertilak.

From the manuscript Cotton Nero A. x, f. 129

Medieval Romance

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, both the code of chivalry and the rituals of courtly love govern Sir Gawain’s behavior and decisions, as would be expected in a medieval romance, a narrative with the following characteristics:

- a plot about knights and their adventures

- improbable, often supernatural, elements

- conventions of courtly love

- standardized characters (the same types of characters appearing in many stories: the chivalrous knight; the beautiful lady; the mysterious old hag)

- repeated events, often repeated in numbers with religious significance such as three

Key Takeaways

- One of the major writers of the Middle Ages is the unidentified Pearl Poet, and one of his major works is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight exhibits literary techniques typical of the alliterative revival.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight reveals vestiges of paganism in a society dominated by Christianity.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight illustrates two concepts important to medieval nobility: chivalry and courtly love.

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight exemplifies the medieval romance genre.

Exercises

- Review the rules of chivalry as reported by Leon Gautier. On which points does Sir Gawain fail to live up to his vows of knighthood?

- How do the tenets of courtly love affect Sir Gawain’s interaction with Lady Bertilak?

- Do you detect any incongruities in the two systems of chivalry and courtly love?

- Describe the two “games” in which Sir Gawain becomes involved. What was the purpose of these two challenges?

- Identify examples of the characteristics of medieval romance apparent in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Resources: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

General Resources

- “Music, Literature and Illuminated Manuscripts.” Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/musicartlit/musicartliterature.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to text, images, and scholarly information. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/gawainre.htm

Modern English Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Verse translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Jessie L. Weston. University of Rochester. The Camelot Project. Prose translation. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/sggk.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Paul Deane. Forgotten Ground Regained: A Treasury of Alliterative and Accentual Poetry. Verse translation. http://alliteration.net/Pearl.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. A. Neilson. In Parentheses. Middle English Series. York University. Prose translation. http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/sggk_neilson.pdf

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Close Verse Translation. Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/ready.htm

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Middle English Arthurian Romance Retold in Modern Prose. Jessie L. Weston. Google Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=j8l7-HnlMfkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=sir+gawain+and+the+green+knight&source=bl&ots=C7I7E8GMVE&sig=cvMDxdXVp1PqOueBlJSEZPjXhpE&hl=en&ei=x2twTMmFKoL7lweM6smADg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=13&ved=0CFsQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&

Original Text

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Dr.Murray McGillivray, University of Calgary, Team Leader. University of Calgary. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/transnew.html

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;rgn=main;view=text;idno=Gawain

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. University of Toronto Libraries. Middle English with prose translation. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

Audio

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. W. H. Neilson. LibriVox. Recording in modern English. http://www.archive.org/details/gawain_mj_librivox

The Pearl Poet

- “The Pearl Poet.” Paul Deane. Forgotten Ground Regained: A Treasury of Alliterative and Accentual Poetry. http://alliteration.net/Pearlman.html

- “The Pearl- (Gawain-) Poet.” Online Companion to Middle English Literature. Chair of Medieval English Literature and Historical Linguistics of the Heinrich-Heine-University Duesseldorf. http://user.phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de/~holteir/companion/Navigation/Authors/Pearl-Poet/pearl-poet.html

Courtly Love

- Andreas Capellanus. The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/authors/andreas/index.html

- Andreas Capellanus: The Art of Courtly Love, (btw. 1174–1186). Paul Halsall. Internet Medieval Sourcebook. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/capellanus.asp

- “Chivalry and Courtly Love.” David L. Simpson. DePaul University. http://condor.depaul.edu/dsimpson/tlove/courtlylove.html

- “’Courtly Love’ Images.” Dr. Debora B. Schwartz. English Department, College of Liberal Arts. California Polytechnic State University. http://cla.calpoly.edu/~dschwart/engl513/courtly/images.htm