This is “Introduction to Middle English Literature: The Medieval World”, section 2.1 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.1 Introduction to Middle English Literature: The Medieval World

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast the comitatus organization of Old English society with medieval feudalism.

- Identify the three estates of medieval society and appraise their function.

- Assess the influence of the Church on the literature of the Middle Ages.

- Understand the correlation between the Church and the concept of chivalry in the Middle Ages.

- Recognize types of religious literature of the Middle Ages, including medieval drama.

- Assess the impact of Caxton’s printing press on the Middle English language and literature.

The world about which Chaucer wrote was a very different world from that which produced Beowulf. Developments in language, new structures in society, and changes in how people viewed the world and their place in it produced literature unlike the heroic literature of the Old English period.

Language

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, Old English was suppressed in records and official venues in favor of the Norman French language. However, the English language survived among the conquered Anglo-Saxons. The peasant classes spoke only English, and the Normans who spread out into the countryside to take over estates soon learned English of necessity. By the 14th century, English reemerged as the dominant language but in a form very different from Anglo-Saxon Old English. Writers of the 13th and 14th centuries described the co-existence of Norman French and the emerging English now known as Middle English.

A medieval university from a 13th-century illuminated manuscript.

Society

In the Middle Ages, the king-retainer structure of Anglo-Saxon society evolved into feudalisma method of organizing society consisting of three estates: clergymen, the noblemen who were granted fiefs by the king, and the peasant class who worked on the fief, a method of organizing society consisting of three estates: clergymen, the noblemen who were granted fiefs by the king, and the peasant class who worked on the fief. Medieval society saw the social order as part of the Great Chain of Beingthe metaphor used in the Middle Ages to describe the social hierarchy believed to be created by God, the metaphor used in the Middle Ages to describe the social hierarchy believed to be created by God. Originating with Aristotle and, in the Middle Ages, believed to be ordained by God, the idea of Great Chain of Being, or Scala Naturae, attempted to establish order in the universe by picturing each creation as a link in a chain beginning with God at the top, followed by the various orders of angels, down through classes of people, then animals, and even inanimate parts of nature. The hierarchical arrangement of feudalism provided the medieval world with three estates, or orders of society: the clergy (those who tended to the spiritual realm and spiritual needs), the nobility (those who ruled, protected, and provided civil order), and the commoners (those who physically labored to produce the necessities of life for all three estates). However, by Chaucer’s lifetime (late 14th century), another social class, a merchant middle class, developed in the growing cities. Many of Chaucer’s pilgrims represent the emerging middle class: the Merchant, the Guildsmen, and even the Wife of Bath.

Philosophy

The Church

The most important philosophical influence of the Middle Ages was the Church, which dominated life and literature. In medieval Britain, “the Church” referred to the Roman Catholic Church.

Canterbury Cathedral.

Although works such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales reveal an exuberant, and often bawdy, sense of humor in the Middle Ages, people also seemed to have a pervasive sense of the brevity of human life and the transitory nature of life on earth.

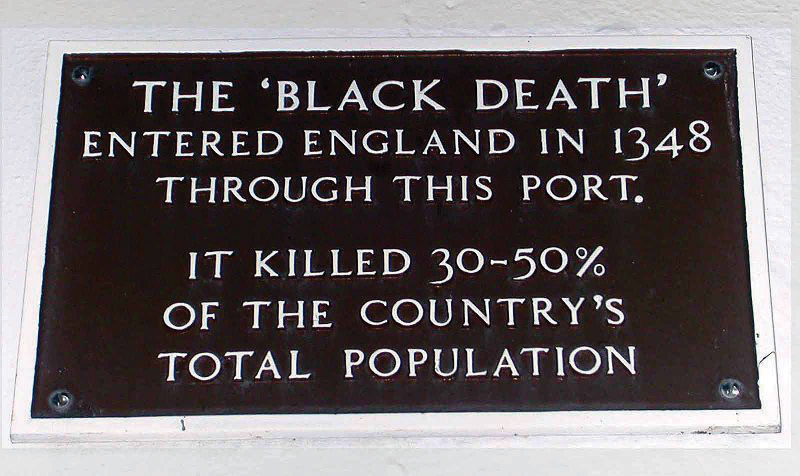

Plaque in Weymouth, England.

Outbreaks of the plague, known as the Black Death, affected both the everyday lives and the philosophy of the Middle Ages. It was not unusual for the populations of entire villages to die of plague. Labor shortages resulted, as did a fear of being near others who might carry the contagion. In households where one member of a family contracted the plague, other members of the family were quarantined, their doors marked with a red x to warn others of the presence of plague in the house. Usually other members of the family did contract and die from the disease although there were instances of individuals, particularly children, dying from starvation after their parents succumbed to plague.

Bodiam Castle.

Even beyond the outbreaks of plague, the Middle Ages were a dangerous, unhealthy time. Women frequently died in childbirth, infant and child mortality rates were high and life expectancies short, what would now be minor injuries frequently resulted in infection and death, and sanitary conditions and personal hygiene, particularly among the poor, were practically non-existent. Even the moats around castles that seem romantic in the 21st century were often little more than open sewers.

With these conditions, it’s not surprising that people of the Middle Ages lived with a persistent sense of mortality and, for many, a devout grasp on the Church’s promise of Heaven. Life on earth was viewed as a vale of tears, a hardship to endure until one reached the afterlife. In addition, some believed physical disabilities and ailments, including the plague, to be the judgment of God for sin.

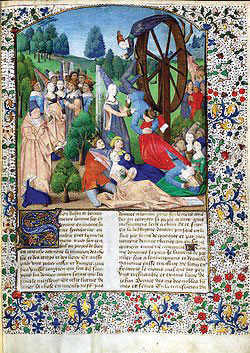

Fortuna spinning her Wheel of Fortune, from a work of Boccaccio.

An important image in the Middle Ages was the wheel of fortune. Picturing life as a wheel of chance, where an individual might be on top of the wheel (symbolic of having good fortune in life) one minute and on the bottom of the wheel the next, the image expressed the belief that life was precarious and unpredictable. In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the monk, for example, tells of individuals who enjoyed good fortune in life until a turn of the wheel brought them tragedy.

The Church incorporated the wheel of fortune in its imagery. Many medieval cathedrals feature rose windows. From the exterior of the church, the stone tracery of the window looks similar to a wheel of fortune; from within the church, sunlight floods through the glass, revealing its beauty. Symbolically, those outside the Church are at the mercy of fortune’s vagaries; those in the Church see the light through the stonework, suggesting the light of truth and faith, the light of Christ, available to those within the Church.

Rose window in the Basilica of St. Francis in Assissi, Italy. Note how the stone tracery from the outside looks like a wheel of fortune. From inside the Church, the light is apparent.

Chivalry

In addition to religion, a second philosophical influence on medieval thought and literature was chivalrythe code of conduct which bound and defined a knight’s behavior, the code of conduct that bound and defined a knight’s behavior.

The ideals of chivalry form the basis of the familiar Arthurian legends, the stories of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Historians generally agree that, if Arthur existed, it was most likely in the time period after the Roman legions left Britain undefended in the fifth century. Arthur was likely a Celtic/Roman leader who, for a time, repelled the invading Anglo-Saxons. However, the King Arthur of the familiar legends is a fictional figure of the later Middle Ages, along with his Queen Guinevere, the familiar knights such as Lancelot and Gawain, his sword Excalibur, Merlin the magician, and his kingdom of Camelot.

The concepts of chivalry and courtly love, unlike King Arthur, were real. The word chivalry, based on the French word chevalerie, derives from the French words for horse (cheval) and horsemen, indicating that chivalry applies only to knights, the nobility. Under the code of chivalry, the knight vowed not only to protect his vassals, as demanded by the feudal system, but also to be the champion of the Church.

Literature

Because the Church and the concept of chivalry were dominant factors in the philosophy of the Middle Ages, these two ideas also figure prominently in medieval literature.

Religious Literature

Religious literature appeared in several genres:

-

devotional books

- books of hours [collections of prayers and devotionals, often illuminated]

- sermons

- psalters [books containing psalms and other devotional material, often illuminated]

- missals [books containing the prayers and other texts read during the celebration of mass throughout the year]

- breviaries [books containing prayers and instructions for celebrating mass]

- hagiographies [stories of the lives of saints]

-

medieval drama

- mystery playsa play depicting events from the Bible [plays depicting events from the Bible]

- morality playsa play depicting representative characters in moral dilemmas with both the good and the evil parts of their character struggling for dominance [plays, often allegories, intended to teach a moral lesson]

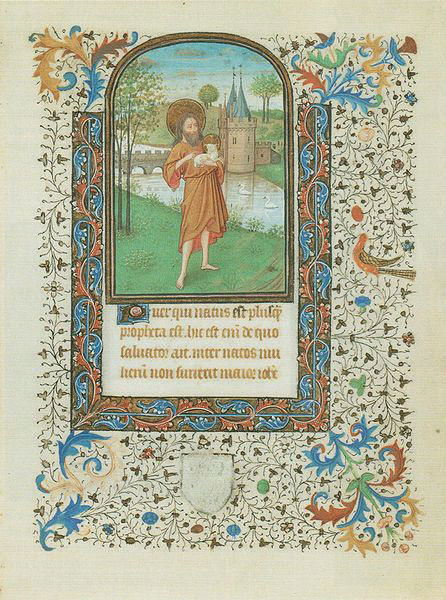

John the Baptist from a medieval book of hours.

Like the oral tradition of the Anglo-Saxon age, mystery plays and morality plays served a predominantly illiterate population.

Britain’s National Trust presents a video describing the Sarum Missal printed by Caxton, an important extant example of the religious literature of the Middle Ages, as well as a second brief video of their turn-the-pages digital copy of the missal that allows a closer inspection of several pages. The British Library features a turn-the-pages digital copy of the Sherborne Missal.

Chivalric Literature

In Britain, chivalric literature, particularly the legends of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, flowered in the medieval romancea narrative, in either prose or poetry, presenting a knight and his adventures, a narrative, in either prose or poetry, presenting a knight and his adventures. The word romance originally indicated languages that derived from Latin (the Roman language) and is not related to modern usage of the word to signify romantic love. Instead a medieval romance presents a knight in a series of adventures (a quest) featuring battles, supernatural elements, repeated events, and standardized characters.

Caxton and the Printing Press

Caxton revolutionized the history of literature in the English language in 1476 when he set up the first printing press in England somewhere in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. The first to print books in English, Caxton helped to standardize English vocabulary and spelling.

The all-encompassing influence of the Church helped create a demand for devotional literature as literacy spread, particularly among the upper and middle classes. Although more people could read, they seldom could read Latin, the language in which clergy recorded most literature. To meet the demand for literature in the vernacular, Caxton printed works in English, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The British Library provides digital images of both the first and second editions that Caxton printed.

Key Takeaways

- After the Norman conquest in 1066, the English language began its gradual transformation from Old English to Middle English.

- Feudalism and chivalry are evident in much Middle English literature.

- The Church was highly influential in daily life of the Middle Ages and in medieval literature.

- William Caxton helped standardize the language and satisfied a demand for literature in the vernacular when he introduced the printing press to England in 1476.

Resources: The Medieval World

Language

- The English Language in the Fourteenth Century. The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. Text, contemporaneous quotations, additional links. http://courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/language.htm

- “The Norman Conquest.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library. http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/changlang/activities/lang/norman/normaninvasion.html

Society

- “Feudal Life.” Annenberg Media Learner.org. Interactives. Text and additional topics. http://www.learner.org/interactives/middleages/feudal.html

- “Feudalism and Medieval Life.” Britain Express. English History. http://www.britainexpress.com/History/Feudalism_and_Medieval_life.htm

- “The Great Chain of Being.” 100 Years of Carnegie. Aristotle. Image and explanation. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/history/carnegie/aristotle/chainofbeing.html

- “Medieval Realms.” Alixe Bovey. Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. Rural life slideshow, text, and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/rural/rurallife.html

- “Towns.” Alixe Bovey. Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. Slideshow, text, and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/towns/medievaltowns.html

Philosophy

- “Black Death.” Mike Ibeji. British History In-Depth. BBC. Text, images, contemporaneous quotation. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/black_01.shtml#top

- “The Black Death: Art.” E.L. Skip Knox. History of Western Civilization. Boise State University. http://www.boisestate.edu/courses/westciv/plague/19.shtml

- “Chivalry.” The End of Europe’s Middle Ages. Applied History Research Group. University of Calgary. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/endmiddle/FRAMES/feudframe.html

- “Church.”Alixe Bovey. Learning: Medieval Realms. British Library. Slideshow, text, and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/thechurch/church.html

- “Death.” Alixe Bovey. Learning Medieval Realms. British Library. Text and images. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/death/medievaldeath.html

- “King Arthur.” Alan Lupack and Barbara Tepa Lupack, Editors. The Camelot Project. University of Rochester. Texts, background, images, bibliographies. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/arthmenu.htm

- “Medieval Tragedy.” Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Image, text, and additional links. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/medievaltragedy.html

- “Religion.” Annenberg Media Learner.org. Interactives. Text and additional topics. http://www.learner.org/interactives/middleages/religion.html

- “The Spread of the Black Death.” Applied History Research Group. University of Calgary. Map and text. http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/endmiddle/bluedot/blackdeath.html

- “Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte Darthur.’” Online Gallery. British Library. information on Malory, Malory’s manuscript, the Arthurian legend, and the historical Arthur. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/englit/malory/index.html

Literature

- The Morality Plays. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Image, text, and additional links. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/moralities.html

- The Mystery Cycles. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Image, text, and additional links. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/mysteries.html

- “The Sarum Missal—Lyme Park, Cheshire.” Turning the Pages of History: The Lyme Caxton Missal. The National Trust. http://youtu.be/hDXki-iiiqM

- “The Sherborne Missal.” Virtual Books. Online Gallery. British Library. http://ttpdownload.bl.uk/app_files/silverlight/default.html?id=181afc99-df1f-4951-8981-df7e26625850

- “Turning the Pages: The Sarum Missal, Lyme Park, Cheshire. The National Trust. http://youtu.be/B0rZyH5U44w

Caxton and the Printing Press

- Caxton’s English. British Library. Treasures in Full. Text, images, additional links. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/english.html

- Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. Treasures in Full. Text, images, additional links. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/caxtonslife.html

- Caxton’s Chaucer. British Library. Treasures in Full. Interactive digital images of the first and second editions of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/homepage.html

- William Caxton and the Printing Press. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College. Video. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lMn5OGJrPU

- William Caxton (c.1422–1492). Historic Figures. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/caxton_william.shtml

- William Caxton and the Printing Press. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College. Video. http://youtu.be/rQ1-9VsUY1o

- William Caxton (c.1422–1492). Historic Figures. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/caxton_william.shtml