This is “Old English Literature”, chapter 1 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Old English Literature

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

1.1 Development of the English Language

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the key influences on the development of the English language.

- Understand the broad timeline of the development of the English language.

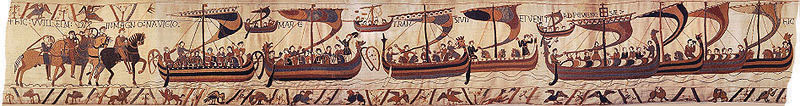

Norman Invasion portrayed in the Bayeux Tapestry.

The English language and English literature began with the recorded history of Britain.

The early history of England includes five invasions which contributed to the development of the English language and influenced the literature:

- the Roman invasion

- the Anglo-Saxon invasions

- the Christian “invasion”

- the Viking invasions

- the Norman French invasion

The Roman Invasion

At the time of the earliest written records, the British islands were inhabited by Celtic people known as the Britons. (See Map 1.) Although the Roman Empire made initial contacts with the Celtic people in Britain around 55 B.C., the Roman invasion of Britain began around A.D. 43. The Celtic people resisted but were unable to fend off the invading Roman troops. One of the principal figures fighting the Romans was the Celtic queen Boudicca. Unlike their Roman counterparts, Celtic societies allotted women rights often equal to those of men. When her husband, an ally of the Romans, died, the Romans took over the land of her tribe, the Iceni, flogging Boudicca and raping her daughters. Boudicca led her people in revolt and for some time managed to hold back the mighty Roman legions.

Roman lighthouse at Dover.

Long familiar with Britain as a source of tin, the Romans conquered Britain around A.D. 44 and set up fortresses, light houses on the coast, and a defensive wall across the entire Northern border of England named Hadrian’s Wall for the Roman emperor Hadrian. As they did in many parts of the world, the Romans built villas with beautiful mosaics, a series of roads which were used for centuries, and great Roman baths, such as those at Aquae Sulis, now known as Bath, England. View a video mini-lecture that explains the Roman invasion.

Roman bath overflow at Bath, England.

How did the Roman invasion affect the development of the English language? While there is no direct linguistic connection, the Roman occupation of Britain and their subsequent abandonment of the country set the stage for the most important invasion, the Anglo-Saxon invasion which provided the foundation of the English language.

The Anglo-Saxon Invasions

At the fall of the Roman Empire (ca. 420), the Roman troops were called back to the continent, and Britain was left undefended. This period of time produced the figure that was transformed in legend into King Arthur. The man who formed the basis of the Arthurian legend was probably a descendent of Celtic and Roman people who led his followers in resisting the Anglo-Saxons. This resistance occurred long before the days of knights in armor mounted on horseback, the picture of King Arthur found in most stories.

Anglo-Saxon ornament in the British Museum.

The Anglo-Saxons were Germanic tribes who began raiding the coastal areas of Britain around 450. (See Map 2.) For over 100 years, the Anglo-Saxons continued to raid and gradually to settle in Britain, pushing the Celtic people into the remote parts of Britain—into what are today the countries of Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. (See Map 3 and Map 4.) With them, they took their Celtic language which formed the basis of the Gaelic languages of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. (See Map 5.) Few Celtic words remain in today’s English; those few are primarily place names such as avon for river (as in the English town Stratford-upon-Avon) and words associated with the countries to which the Celts dispersed such as glen (valley), loch (lake), and cairn (pile of stones) from Scotland.

The Anglo-Saxon Germanic Language Is the Foundation of the English Language

The culture of the Anglo-Saxons is much in evidence in Old English literature, especially in the concept of the Germanic heroic ideal. The primary attribute of the heroic ideal was excellence—excellence in all that was important to the tribe: hunting, sea-faring, fighting. The leader of each tribal unit, often family units especially in earlier years, gained his position because of his physical strength and capabilities in the activities necessary for survival. Each man of the tribe, called a thanean Anglo-Saxon warrior loyal to a specific leader or retainer, an Anglo-Saxon warrior loyal to a specific leader, swore his allegiance, and in return his leader rewarded him with the spoils of their battles and raids. A group of Anglo-Saxon warriors bound by the reciprocal king-retainer relationship was known as a comitatusa group of Anglo-Saxon warriors bound by the reciprocal king-retainer relationship. An example is the group of Geats led by Beowulf.

These Anglo-Saxon tribes led violent lives governed as they believed by wyrdthe Anglo-Saxon word for fate, the power that controls one’s destiny, the Anglo-Saxon word for fate, the power that controls one’s destiny, and bound by loyalty to their comitatus, including the obligation of exacting revenge for their comrades. A formal system of wergilda price placed on a man’s life and paid in lieu of blood revenge, a price placed on a man’s life and paid in lieu of blood revenge, provided an honorable way to end a feud or to satisfy the demands of revenge.

By the year 700, various tribes settled in different parts of Britain, each with its own dialect. (See Map 6.) The language generally known as Old English came primarily from the dialect of the West Saxons, located in an area known as Wessex.

Although mostly illiterate, the Anglo-Saxons had a rich tradition of oral literature. Gathered in the mead hall with its long tables around a central hearth, the Anglo-Saxons listened to tales of battle glory sung or chanted to the strums of a harp. The scopthe tribal poet/singer, the tribal poet/singer, entertained and commemorated significant events by composing and performing tales such as Beowulf. Although many scholars have varying ideas about how these performances might have sounded, little is known of secular music during this time period, and there is of course no evidence to suggest whether the songs were more like chants with strums of the harp perhaps in the caesura or whether they were lively, rambunctious, melodic performances. We might remember that in Beowulf, it’s the sound of laughter, the music of the harp, and the singing of the scop that drives Grendel to attack Heorot.

Reconstruction of Anglo-Saxon harp from remnants in Sutton Hoo.

The Anglo-Saxon invasion established the English language and the earliest English literature. The next important step, the recording of that literature, came with the return of Christianity to Britain.

The Christian “Invasion”

Although certainly not a military invasion like the others in the list, the arrival of Christianity in Britain was as influential on the language and the culture, and therefore on the literature. Christianity was not unknown in Britain when St. Augustine arrived in 597 but had appeared during the time of the Romans. However, Christianity was suppressed along with the Celtic tribes during the Anglo-Saxon invasions. In 597, St. Augustine arrived on a mission to Christianize the pagan Anglo-Saxons, and the literature of the time bears witness to his influence. During the same time period, Celtic Christianity continued to spread from the northern and western reaches. The Anglo-Saxons were mostly illiterate; therefore, their oral stories were not written until the Christian monks recorded them. Many twentieth-century scholars believed that Beowulf, for example, was originally a pagan story and that references to Christianity are interpolations made by the recording monks in their reluctance to perpetuate strictly pagan literature or as a way of converting still-pagan Anglo-Saxons. Most scholars now believe that Beowulf was more likely composed by a Christian author who drew on and perhaps paid homage to his pagan roots.

Burial site of St. Augustine’s successor Laurence in the abbey ruins.

Ruins of St. Augustine’s Abbey.

Many words with Latin roots found their way into the English language with the assimilation of Christianity into the culture, many of them words for religious concepts for which the Anglo-Saxons had no terms, such as angel, priest, martyr, bishop.

The establishment of monasteries in Britain also led to the production of beautifully illuminated manuscripts, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels. The British Library’s Virtual Books Online Gallery allows you to virtually turn the pages of the Lindisfarne gospels.

The Viking Invasions

Between 750 and 1050, another group of war-like, pagan tribes raided Britain and gradually established settlements, primarily in the north and east of England. The Vikings were from the area now known as Scandinavia. While they shared cultural similarities with the Anglo-Saxons, they brought their own language, another impact on the developing English language. Words such as sky, skin, wagon originated with the language of the Vikings.

Ruins of Lindisfarne Priory.

Sidebar 1.1.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (translated by E. E. C. Gomme, 1909) describes the Viking raid on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne:

“Here terrible portents came about over the land of Northumbria, and miserably frightened the people: these were immense flashes of lightening, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air. A great famine immediately followed these signs; and a little after that in the same year on 8 June the raiding of heathen men miserably devastated God’s church in Lindisfarne island by looting and slaughter.”

These fishing huts on the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne are built in the shape of overturned Viking boats, still suggesting the Viking heritage of this area as a result of the Viking raiding parties and the eventual coming of Viking settlers. The English language also retains evidence of the Viking influence. In northeastern England, place names recall their Viking settlers: York from Jorvik and Whitby from the Viking by meaning a farm.

Alfred the Great negotiated a peaceful settlement with the Vikings by partitioning Britain in what was known as the Danelaw, establishing a period of relatively peaceful coexistence in which the language and the culture mingled.

The Norman Invasion

The year 1066 is possibly the most important date in the history of Britain and in the development of the English language. When William the Conqueror defeated the English King Harold at the Battle of Hastings, he brought to England a new language and a new culture. Old French became the language of the court, of the government, the church, and all the aristocratic entities. Old English, the language of the Anglo-Saxons, existed only among the conquered lower orders of society. However, within three to four hundred years, the English language emerged, greatly enriched by French vocabulary and distinctly different from the Anglo-Saxons’ Old English, Chaucer’s language, now referred to as Middle English.

Pevensy Castle ruins—Pevensy Castle was built by William the Conqueror on ruins of Roman and Anglo-Saxon settlements.

Video Clip 6

The Norman Invasion: William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings

(click to see video)The British Library provides an interactive timeline that traces the development of the English language, beginning with Beowulf.

Key Takeaways

-

The development of the English language was influenced by 5 events:

- the Roman invasion

- the Anglo-Saxon invasions

- the Christian “invasion”

- the Viking invasions

- the Norman invasion

- The Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxons, known as Old English, is the foundation of the English language.

Exercises

- Construct a timeline which includes key events in the development of the English language.

- On a map of the British Isles, locate areas of Roman settlements, Celtic settlements after the Roman invasion, Anglo-Saxon settlements, Canterbury (the site of St. Augustine’s church and monastery), Viking settlements, and the Holy Island of Lindisfarne.

- On a contemporary map of England, locate cities whose names contain recognizable Roman influence such as castor or cester and wich or wick; Anglo-Saxon influence such as stow, ham, ton, or bury; Viking influence such as by, thorpe, or thwaite; and Norman influence such as beau, bel, ville, or mont.

Resources

Maps

- Celtic Peoples of Roman Britain. Britannia History.

- Roman “Saxon Shore” Forts. Britannia History

- Saxon Invasions and Land Holdings. Britannia History

- Saxon Tribes and Celtic Holdings. Britannia History

- Saxon Control. Britannia History

General Background

- English Language and Literature Timeline. British Library.

The Britons

- “Arthur: King of the Britons.” David Nash Ford. Britannia.

- “Boudicca. The Celtic Arts and Cultures Website. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- “Britons (Celts). John Weston. Data Wales.

-

British Museum Online Tours:

The Romans

- Hadrian’s Wall. “Hadrian: Empire and Conflict.” The British Museum.

The Anglo-Saxon Invasions

- “Alfred the Great.” Monarchs. Britannia.

- “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.” The Online Medieval and Classical Library.

- “The Anglo-Saxon Fyrd c.400–878 A.D.” Ben Levick. Regia Anglorum.

The Arrival of Christianity

- “St. Augustine of Canterbury.” Terry H. Jones. Saints.SPQN.com.

- Lindisfarne Gospels. Virtual Books. Online Gallery. The British Library.

- “The Venerable Bede (672–735).” Religion Facts.

The Viking Invasions

- “The Danelaw.” Britannia.

Videos

- “The Anglo-Saxon Invasion: Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Exhibit.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “The Christian Invasion: St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “The Lindisfarne Gospels.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “The Norman Invasion: William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “The Roman Invasion: Boudicca and the Celts.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “The Viking Invasion: Chester, England.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Medieval Manuscripts

- Catalogue of Digitized Medieval Manuscripts. Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. University of California, Los Angeles.

- Digital Scriptorium. Columbia University and University of California, Berkeley.

1.2 “Caedmon’s Hymn” and the Venerable Bede

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the elements of Anglo-Saxon culture revealed in Bede’s story of Caedmon.

- Identify the Venerable Bede and appraise the importance of his work in our knowledge of Anglo-Saxon culture in Britain.

The Venerable Bede

The Venerable Bede, a monk from Northumbria, is the most important historian of the Anglo-Saxon period primarily because of his work the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Although little is known about his life, Bede likely was born about 672 or 673 to a noble family and sent to the monastery of Wearmouth to be educated.

Death of St. Bede.

From his monastery at Jarrow, Bede visited the monastery on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and wrote two books about the life and miracles of St. Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne Priory from 685–687. Both St. Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede are buried at Durham Cathedral.

Durham Cathedral.

Ecclesiastical History of the English People

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People records two important events that occurred at another abbey in northern England, the Abbey of Whitby.

Ruins of Whitby Abbey.

The Abbey of Whitby overlooks the North Sea in North Yorkshire, England. Founded in 657, the abbey’s first abbess Hilda was the niece of Edwin, the first Christian king of Northumbria.

The Venerable Bede records the story of King Edwin’s conversion to Christianity. Considering converting as part of a marriage arrangement, King Edwin asked some of his counselors for advice. The Venerable Bede records the advice that one of his counselors gave him:

Sidebar 1.2.

The present life man, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the room wherein you sit at supper in winter amid your officers and ministers, with a good fire in the midst whilst the storms of rain and snow prevail abroad; the sparrow, I say, flying in at one door and immediately out another, whilst he is within is safe from the wintry but after a short space of fair weather he immediately vanishes out of your sight into the dark winter from which he has emerged. So this life of man appears for a short space but of what went before or what is to follow we are ignorant. If, therefore, this new doctrine contains something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed.

Like the Abbey at Lindisfarne, the Abbey at Whitby was sacked by Viking raiders and rebuilt. Also like other abbeys in England, it was closed at the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in 1536.

But long before Henry VIII, Whitby Abbey was home to Caedmon.

Recorded by the Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, “Caedmon’s Hymn” is the oldest extant work in the Old English language. It was probably composed during the latter half of the 7th century.

Part of this work’s importance is what it reveals about Anglo-Saxon society nearly one hundred years after the arrival of St. Augustine in 597. The poem pictures an Anglo-Saxon society in which the tribe gathers in the mead hall to eat and to entertain each other with songs about heroes and their adventures. But, in this story, for the first time, one of those traditional songs has a religious theme, illustrating the influence of Christianity on the pagan culture.

In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the Venerable Bede records the story of Caedmon, a simple, uneducated cow herder at the Abbey of Whitby who was given the gift of song in a dream/vision. Like others in Anglo-Saxon society, the monks followed the custom of passing around a harp after the evening meal in the great hall for everyone to take a turn singing/chanting a story. Caedmon used to sneak out before it was his turn because he couldn’t sing. Then he received his divine gift. The important point, however, is that he was given the gift of singing stories about religious subjects, specifically the creation of the world.

Caedmon’s cross near Whitby Abbey.

Sidebar 1.3.

Caedmon’s Hymn

Now praise the guardian of Heaven,

the might of the Creator, and his purpose,

the work of the Father of glory, how each of wonders

the Eternal Lord established in the beginning.

He, the holy Creator, first created

Heaven as a roof for the sons of men.

The holy Creator, the guardian of mankind,

the Eternal Lord, the Almighty Lord

afterwards made Middle-earth, the earth for men.

In the beginning Cædmon sang this poem.

Anglo-Saxon songs and stories were always about battles, heroic but violent deeds, monsters—stories like Beowulf. The story of Caedmon pictures the use of the Anglo-Saxon custom of singing in the mead hall to introduce Christian stories to the pagan Anglo-Saxons.

Illuminated Manuscripts

After the Anglo-Saxon invasions and before the Norman Conquest, literacy in Britain was almost entirely the province of the monasteries. As we see in Bede’s The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, monks were responsible for the recording of what history and literature exists from the Anglo-Saxon period.

One of the highlights of this period was the production of illuminated manuscriptshandwritten manuscripts adorned with richly colorful, intricately crafted illustration, often using expensive materials such as gold leaf, handwritten manuscripts adorned with richly colorful, intricately crafted illustration, often using expensive materials such as gold leaf. One of the most famous illuminated manuscripts is the Lindisfarne Gospels. The British Library’s online virtual books feature allows you the experience of leafing through this rare and valuable manuscript.

Key Takeaways

- The Venerable Bede’s The Ecclesiastical History of the English People is one of the few sources of information about Britain in the Anglo-Saxon period.

- The story of Caedmon the cow herder may have been composed to account for the introduction of religious topics to the Anglo-Saxon story-telling tradition.

- The creation of illuminated manuscripts is a highlight of medieval literature and art.

Exercises

- Read the story of Caedmon in The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. What do you learn about daily life in a monastery from reading this passage? What do you learn about Anglo-Saxon culture?

- After reading the story of Caedmon, how would you characterize Bede’s work? What would you consider the main purpose of his work?

- Describe what you consider the outstanding features of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

Resources

Biographical Information on Caedmon

- “Caedmon.” Dictionary of National Biography.

- “St. Caedmon.” The Catholic Encyclopedia.

Biographical Information on The Venerable Bede

- Biography of The Venerable Bede. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- Image of Bede’s tomb in Durham Cathedral. Durham Cathedral.

- The Venerable Bede. BBC. Audio of panel consisting of Richard Gameson, Reader in Medieval History at the University of Kent at Canterbury; Sarah Foot, Professor of Early Medieval History at the University of Sheffield; Michelle Brown, manuscript specialist from the British Library.

- “The Venerable Bede.” History. Historic Figures. BBC.

- “The Venerable Bede.” Religion Facts. Biography and images of Bede and Bede’s tomb.

Text of “Caedmon’s Hymn”

- “Caedmon’s Hymn.” Poemhunter.com. Old English and Modern English.

- “Caedmon’s Hymn.” Representative Poetry Online. Old English and Modern English with commentary by Ian Lancashire, Dept. of English, University of Toronto.

Audio

- Anglo-Saxon Aloud. Michael D. C. Drout. Wheaton College. Recording in Old English.

- “Caedmon’s Hymn.” Internet Archive. Librivox. Recording in Old English.

- “Caedmon’s Hymn.” Project Gutenberg. Recording in Modern English.

Video

- “The Venerable Bede and ‘Caedmon’s Hymn.’” Dr. Carol A. Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Ecclesiastical History of England Text

- Ecclesiastical History of England. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- “Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation.” Internet Medieval Sourcebook. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies. text in Modern English.

- Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Thomas Miller. In Parentheses. Old English Series. York University, Canada.

- Story of Caedmon from Ecclesiastical History. Internet Sacred Text Archive.

Illuminated Manuscripts

- Fathom The Lindisfarne Gospels. Michelle P. Brown, Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts, British Library. Seminar on the history of illuminated manuscripts including images.

- Fathom: An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts. Michelle P. Brown, Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts, British Library. Seminar on the history of Anglo-Saxon manuscripts including images.

- Pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon Art: the Lindisfarne Gospels. Online Gallery. Virtual Books. British Library.

1.3 “The Dream of the Rood”

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize and account for both pagan and Christian elements in “The Dream of the Rood.”

- Interpret the poem’s characterization of Christ in terms of the Anglo-Saxon culture.

“The Dream of the Rood” tells a Christian story with emphasis on elements that would appeal to the pagan warrior society of the Anglo-Saxons. Note the use of epithetscharacterizing words or phrases used in place of a proper name (characterizing words or phrases used in place of a proper name). For example, the cross is referred to as “wondrous wood,” “victor-tree,” and “ the Saviour’s tree.” Each epithet suggests a characteristic of the cross. Like much Old English poetry, “The Dream of the Rood” exemplifies an elegiac tonean awareness of the transitory nature of life, human sinfulness and sorrow, and the promised consolation of Heaven, an awareness of the transitory nature of life, human sinfulness and sorrow, and the promised consolation of Heaven.

Told by two narrators, the unnamed Dreamer and the Rood, the poem is an example of dream vision literaturea narrative in which an individual experiences a dream or vision which substantially changes his/her life, frequently through the wisdom of a guide or mentor, a narrative in which an individual experiences a dream or vision which substantially changes his/her life, frequently through the wisdom of a guide or mentor. In this case the Rood, the cross upon which Christ was crucified, relates his experiences in the terms of a loyal retainer supporting his king.

Text: “The Dream of the Rood”

(translated by James M. Garnett, Boston: Ginn & Co., Publishers, The Athenaeum Press, 1911. rpt. in Project Gutenberg)

| Lo! choicest of dreams I will relate, | |

| What dream I dreamt in middle of night | |

| When mortal men reposed in rest. | |

| Methought I saw a wondrous wood | |

| Tower aloft with light bewound, | 5 |

| Brightest of trees; that beacon was all | |

| Begirt with gold; jewels were standing | |

| Four at surface of earth, likewise were there five | |

| Above on the shoulder-brace. All angels of God beheld it, | |

| Fair through future ages; ‘twas no criminal’s cross indeed, | 10 |

| But holy spirits beheld it there, | |

| Men upon earth, all this glorious creation. | |

| Strange was that victor-tree, and stained with sins was I, | |

| With foulness defiled. I saw the glorious tree | |

| With vesture adorned winsomely shine, | 15 |

| Begirt with gold; bright gems had there | |

| Worthily decked the tree of the Lord. | |

| Yet through that gold I might perceive | |

| Old strife of the wretched, that first it gave | |

| Blood on the stronger [right] side. With sorrows was I oppressed, | 20 |

| Afraid for that fair sight; I saw the ready beacon | |

| Change in vesture and hue; at times with moisture covered, | |

| Soiled with course of blood; at times with treasure adorned. | |

| Yet lying there a longer while, | |

| Beheld I sad the Saviour’s tree | 25 |

| Until I heard that words it uttered; | |

| The best of woods gan speak these words: | |

| “‘Twas long ago (I remember it still) | |

| That I was hewn at end of a grove, | |

| Stripped from off my stem; strong foes laid hold of me there, | 30 |

| Wrought for themselves a show, bade felons raise me up; | |

| Men bore me on their shoulders, till on a mount they set me; | |

| Fiends many fixed me there. Then saw I mankind’s Lord | |

| Hasten with mickle might, for He would sty upon me. | |

| There durst I not ‘gainst word of the Lord | 35 |

| Bow down or break, when saw I tremble | |

| The surface of earth; I might then all | |

| My foes have felled, yet fast I stood. | |

| The Hero young begirt Himself, Almighty God was He, | |

| Strong and stern of mind; He stied on the gallows high, | 40 |

| Bold in sight of many, for man He would redeem. | |

| I shook when the Hero clasped me, yet durst not bow to earth, | |

| Fall to surface of earth, but firm I must there stand. | |

| A rood was I upreared; I raised the mighty King, | |

| The Lord of Heaven; I durst not bend me. | 45 |

| They drove their dark nails through me; the wounds are seen upon me, | |

| The open gashes of guile; I durst harm none of them. | |

| They mocked us both together; all moistened with blood was I, | |

| Shed from side of the man, when forth He sent His spirit. | |

| Many have I on that mount endured | 50 |

| Of cruel fates; I saw the Lord of Hosts | |

| Strongly outstretched; darkness had then | |

| Covered with clouds the corse of the Lord, | |

| The brilliant brightness; the shadow continued, | |

| Wan ‘neath the welkin. There wept all creation, | 55 |

| Bewailed the King’s death; Christ was on the cross. | |

| Yet hastening thither they came from afar | |

| To the Son of the King: that all I beheld. | |

| Sorely with sorrows was I oppressed; yet I bowed ‘neath the hands of men, | |

| Lowly with mickle might. Took they there Almighty God, | 60 |

| Him raised from the heavy torture; the battle-warriors left me | |

| To stand bedrenched with blood; all wounded with darts was I. | |

| There laid they the weary of limb, at head of His corse they stood, | |

| Beheld the Lord of Heaven, and He rested Him there awhile, | |

| Worn from the mickle war. Began they an earth-house to work, | 65 |

| Men in the murderers’ sight, carved it of brightest stone, | |

| Placed therein victories’ Lord. Began sad songs to sing | |

| The wretched at eventide; then would they back return | |

| Mourning from the mighty prince; all lonely rested He there. | |

| Yet weeping we then a longer while | 70 |

| Stood at our station: the [voice] arose | |

| Of battle-warriors; the corse grew cold, | |

| Fair house of life. Then one gan fell | |

| Us all to earth; ‘twas a fearful fate! | |

| One buried us in deep pit, yet of me the thanes of the Lord, | 75 |

| His friends, heard tell; [from earth they raised me], | |

| And me begirt with gold and silver. | |

| Now thou mayst hear, my dearest man, | |

| That bale of woes have I endured, | |

| Of sorrows sore. Now the time is come, | 80 |

| That me shall honor both far and wide | |

| Men upon earth, and all this mighty creation | |

| Will pray to this beacon. On me God’s Son | |

| Suffered awhile; so glorious now | |

| I tower to Heaven, and I may heal | 85 |

| Each one of those who reverence me; | |

| Of old I became the hardest of pains, | |

| Most loathsome to ledes [nations], the way of life, | |

| Right way, I prepared for mortal men. | |

| Lo! the Lord of Glory honored me then | 90 |

| Above the grove, the guardian of Heaven, | |

| As He His mother, even Mary herself, | |

| Almighty God before all men | |

| Worthily honored above all women. | |

| Now thee I bid, my dearest man, | 95 |

| That thou this sight shalt say to men, | |

| Reveal in words, ‘tis the tree of glory, | |

| On which once suffered Almighty God | |

| For the many sins of all mankind, | |

| And also for Adam’s misdeeds of old. | 100 |

| Death tasted He there; yet the Lord arose | |

| With His mickle might for help to men. | |

| Then stied He to Heaven; again shall come | |

| Upon this mid-earth to seek mankind | |

| At the day of doom the Lord Himself, | 105 |

| Almighty God, and His angels with Him; | |

| Then He will judge, who hath right of doom, | |

| Each one of men as here before | |

| In this vain life he hath deserved. | |

| No one may there be free from fear | 110 |

| In view of the word that the Judge will speak. | |

| He will ask ‘fore the crowd, where is the man | |

| Who for name of the Lord would bitter death | |

| Be willing to taste, as He did on the tree. | |

| But then they will fear, and few will bethink them | 115 |

| What they to Christ may venture to say. | |

| Then need there no one be filled with fear | |

| Who bears in his breast the best of beacons; | |

| But through the rood a kingdom shall seek | |

| From earthly way each single soul | 120 |

| That with the Lord thinketh to dwell.” | |

| Then I prayed to the tree with joyous heart, | |

| With mickle might, when I was alone | |

| With small attendance; the thought of my mind | |

| For the journey was ready; I’ve lived through many | 125 |

| Hours of longing. Now ‘tis hope of my life | |

| That the victory-tree I am able to seek, | |

| Oftener than all men I alone may | |

| Honor it well; my will to that | |

| Is mickle in mind, and my plea for protection | 130 |

| To the rood is directed. I’ve not many mighty | |

| Of friends on earth; but hence went they forth | |

| From joys of the world, sought glory’s King; | |

| Now live they in Heaven with the Father on high, | |

| In glory dwell, and I hope for myself | 135 |

| On every day when the rood of the Lord, | |

| Which here on earth before I viewed, | |

| In this vain life may fetch me away | |

| And bring me then, where bliss is mickle, | |

| Joy in the Heavens, where the folk of the Lord | 140 |

| Is set at the feast, where bliss is eternal; | |

| And may He then set me where I may hereafter | |

| In glory dwell, and well with the saints | |

| Of joy partake. May the Lord be my friend, | |

| Who here on earth suffered before | 145 |

| On the gallows-tree for the sins of man! | |

| He us redeemed, and gave to us life, | |

| A heavenly home. Hope was renewed, | |

| With blessing and bliss, for the sufferers of burning. | |

| The Son was victorious on that fateful journey, | 150 |

| Mighty and happy, when He came with a many, | |

| With a band of spirits to the kingdom of God, | |

| The Ruler Almighty, for joy to the angels | |

| And to all the saints, who in Heaven before | |

| In glory dwelt, when their Ruler came, | 155 |

| Almighty God, where was His home. |

The Ruthwell Cross

Part of the poem “The Dream of the Rood” is inscribed on the Ruthwell Cross, an 18-foot tall, free standing cross, one of oldest extant Christian monuments in Britain.

The stone is carved with scenes from the Bible, decorative vine work, and 18 lines of “The Dream of the Rood” in Anglo-Saxon runes and Latin lettering. Scholars believe the cross could have been carved after 650, probably after the Synod of Whitby in 664; others think it may have been carved as late as 710.

The Ruthwell Cross, a preaching cross, originally stood outdoors at a crossroad. Because the Anglo-Saxons were mostly illiterate, one of the ways the missionary Christian monks communicated knowledge about the Bible and Christianity was through pictures. Pagan people who saw the cross might be influenced to convert to Christianity or the first Christian converts could be taught biblical knowledge.

The Vercelli Book

Only four manuscripts contain all extant Old English literature: the Junius manuscript (which includes “Caedmon’s Hymn”), the Exeter Book, the Nowell Codex (which includes the Beowulf manuscript), and the Vercelli Book (so called because it was found in Vercelli, Italy). The Vercelli Book contains two poems by Cynewulf, whom some scholars believe may also have composed “The Dream of the Rood.”

Key Takeaways

- “The Dream of the Rood” is a Christian story presented in terms of the Germanic heroic ideal.

- “The Dream of the Rood” exemplifies typical literary devices of Old English literature such as elegiac tone and dream vision format.

Exercises

- In “The Dream of the Rood,” there are two speakers. Who speaks the first and last stanzas? Who speaks the middle stanza in quotation marks?

- “The Dream of the Rood” pictures Christ as a Germanic hero. List some of the epithets for Christ found in “The Dream of the Rood.” What qualities of Christ are emphasized by these epithets? Why is he portrayed that way?

- Also note the epithets used for the cross. What qualities are emphasized by these epithets?

- Describe the mood of the Dreamer in the first paragraph and in the last paragraph. What consolation is revealed to him?

Resources

Text in Modern English

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Charles Kennedy. In Parentheses. Old English Series. York University, Canada.

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Jonathan A. Glenn. University of Central Arkansas. Text with annotations.

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Oxford University. Old English text, multiple modern English translations, background information, and images.

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Project Gutenberg.

- The Dream of the Rood: An Electronic Edition. Mary Rambaran-Olm. University of Glasgow. Text with glossary in both Old and Modern English and images of the manuscript.

Text in Old English

- “Dream of the Rood.” Labyrinth. Georgetown University.

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Oxford University. Old English text, multiple modern English translations, background information, and images.

- The Dream of the Rood: An Electronic Edition. Mary Rambaran-Olm. University of Glasgow. Text with glossary in both Old and Modern English and images of the manuscript.

- The Dream of the Rood: An Old English Poem Attributed to Cynewulf. Albert S. Cook. Internet Archive.

Audio Text in Old English

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Anglo-Saxon Aloud. Michael D. C. Drout. Wheaton College.

Video

- “The Ruthwell Cross and the Dream of the Rood.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Old English Manuscripts

Exeter Book

- “11th Century: The Exeter Book of Old English Poetry.” Facsimiles of Illuminated Manuscripts in Special Collections. The University of Arizona Library Special Collections.

Junius Manuscript

- MS. Junius 11. Bodleian Library. Oxford University.

- Image from MS. Junius 11, p. 2. Bodleian Library. Oxford University. Dr. Felicia Steele, The College of New Jersey.

Nowell Codex

- Image from Beowulf. Online Gallery. British Library.

Vercelli Book

- The Dream of the Rood: An Electronic Edition. Mary Rambaran-Olm. University of Glasgow. Text with glossary in both Old and Modern English and images of the manuscript.

- Digital Images of the Vercelli Book. Oxford University.

The Ruthwell Cross

- “The Dream of the Rood.” Oxford University. Old English text, multiple modern English translations, background information, and images.

- Ruthwell Cross Factsheet. Birth of a Nation History Trails. BBC.

Manuscript and Author

- The Dream of the Rood: An Old English Poem Attributed to Cynewulf. Albert S. Cook. Internet Archive.

1.4 Beowulf

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Trace the history of the Beowulf manuscript.

- Interpret theories of structure and theme in Beowulf.

- Define the oral formulaic tradition and give examples of its use in Beowulf.

- Identify major characters and settings in Beowulf.

- List literary techniques typical of Old English poetry, including Beowulf, and provide examples.

Beowulf is the oldest epic poem written in English and is probably the most important extant Old English literary work. It exists in only one manuscript, the Nowell Codex of the British Library MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv. Julian Harrison, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, British Library, provides a comprehensive introduction to Beowulf in “What Is Beowulf?”

Text

- Beowulf. Clarence Griffin Child. In Parentheses. Old English Series. York University, Canada. Modern English prose translation.

- Beowulf. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Gummere translation. Project Gutenberg. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Old English text. Project Gutenberg.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Gummere’s Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Klaeber’s Old English edition.

- Beowulf in Hypertext. Dr. Anne Savage. McMaster University. Old English and modern English texts.

Audio in Old English

- “Anglo-Saxon Aloud.” Professor Michael D. C. Drout. Wheaton College.

- “Beowulf.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “Readings from Beowulf.” Old English at the University of Virginia. Peter S. Baker. University of Virginia.

Composition

Although the events in the poem take place in the 5th century, the poem was likely composed somewhere from the 8th century to the early 11th century. No one, however, knows exactly when the poem was composed or who composed it. It is also possible that the poem had existed through generations as an oral work.

Subject

Although Beowulf is considered the first great English poem, the events are set in what is now Scandinavia. Beowulf and his people, the Geats, are from an area that is now part of Sweden; Hrothgar is king of the Danes. The culture portrayed, however, is the Anglo-Saxon culture using the language brought to Britain beginning with the 5th-century Anglo-Saxon invasions. View a video about the Sutton Hoo ship burial, an archaeological source of much information about the culture portrayed in Beowulf.

Structure

Some scholars see Beowulf as having a two-part structure:

- Beowulf in his prime, fighting Grendel and his mother for the Danes

- Beowulf in old age, fighting the dragon for his own people, the Geats

Other scholars see the structure as corresponding to the three battles:

- Beowulf against Grendel

- Beowulf against Grendel’s mother

- Beowulf against the dragon

Theme

One theme of Beowulf involves the preservation of the Anglo-Saxon societal structure. Every society worries that their values and standards will be abandoned and that their social order will die out as a result. An elegiac tone and a mood of longing for the past permeates the epic Beowulf. At the end of the poem, Wiglaf mourns both the death of Beowulf and the potential passing of his tribe, vulnerable to attack because their reputation for cowardice will spread among other tribes after the retainers fail in their vows of loyalty.

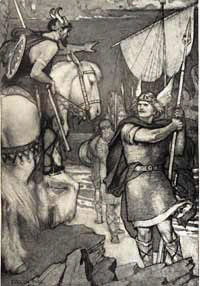

Beowulf challenged by the coast guard by Evelyn Paul, from Guerber’s Myths & Legends of the Middle Ages (1911).

Anglo-Saxon society was based on the Germanic heroic idealthe standard of excellence required of a leader, excellence in all that was important to the tribe: hunting, sea-faring, fighting, the standard of excellence required of a leader, excellence in all that was important to the tribe: hunting, sea-faring, fighting. The leader of each tribal unit, often family units especially in earlier years, gained his position because of his physical strength and capabilities in the activities necessary for survival. The men of the tribe, the thanes or retainers, swore loyalty to the leader and in return he rewarded them with the spoils of their battles and raids.

An important part of the Germanic heroic ideal was the king-retainer relationshipa reciprocal relationship which dictated that the thanes should be loyal to their leader and in return the leader would protect them and share the treasures obtained in battle with them, a reciprocal relationship which dictated that the thanes should be loyal to their leader and in return the leader would protect them and share the treasures obtained in battle with them. The group bound by this relationship, the comitatus, formed the basis of Anglo-Saxon society.

Theme and 3-Part Structure

The theme of concern for cultural values, in this case the comitatus, plays out in the details of the three battles:

- first battle: Beowulf has the “home field” advantage because he fights with Grendel in the mead hall, and he defeats the monster with his bare hands. During the fight, his retainers and Hrothgar’s retainers all stand close by in case Beowulf needs help. They won’t interfere unless Beowulf needs them because they don’t want to detract from their leader’s glory in battle.

- second battle: Beowulf has to go into the monster’s home territory to fight Grendel’s mother, and he has to use a sword—which suggests his strength isn’t quite as great. Not only does Beowulf use Hrunting, the sword Unferth presented him, but when Hrunting fails, Beowulf finds an enormous sword, a sword made by giants (perhaps an ancient Roman sword) which he uses to kill Grendel’s mother. When they see the blood bubbling up through the mere, Hrothgar’s retainers are not faithful—they give up and go home, assuming Beowulf is dead. Only Beowulf’s personal retainers stay at the mere until he returns. There seems to be a direct connection between the loyalty of the retainers and Beowulf’s strength.

- third battle: Fifty years later Beowulf fights the dragon in its lair. All the retainers except Wiglaf abandon their leader and run to hide in the woods. Beowulf not only has to use a weapon to kill the dragon, but he also has to have help from Wiglaf. Again Beowulf’s strength fades as his retainers fail in loyalty.

Notice the speeches that Wiglaf makes to the cowardly retainers. He shames them for running, and he even tells them that now their society will fall. Other tribes will hear about how cowardly they are and, believing them to be easy targets, will come to attack them. The three battles, then, form the structure of the poem and suggest the theme of failing values.

Oral Formulaic Tradition

Many scholars believe that the story of Beowulf existed in oral tradition, perhaps for hundreds of years, before it was recorded in writing, the story told around the fires of the mead hall by the scopthe singer, the shaper or creator of tales, the singer, the shaper or creator of tales. The scop may have used certain memory aids to help him remember the long story, one of which was the formulaa set pattern of words, a set pattern of words. For example: “Þæt wæs god cyning” in line 11 (line numbers may differ according to the translation consulted) of the Prologue uses the formula “Þæt wæs X Y.” The X and Y are filled in with different words each time the formula is used.

- in line 11, “Þæt wæs god cyning” [that was good king]

- in line 170, “Þæt wæs wræc micel” [that was much misery]

- in line 309 “Þæt wæs foremærost” [that was most famous {hall}]

- in line 348 “Þæt wæs Wendla leod” [that was the Wendles’ (Vandals’) chieftain]

- in line 705 “Þæt wæs yldum cuÞ“ [that was widely known]

- in line 765 “Þæt wæs geocor sið“ [that was terrible journey]

- in line 834 “Þæt wæs tacen sweotol” [that was clear symbol]

- in line 864 “Þæt wæs god cyning” [that was good king]

- in line 1039 “Þæt wæs hilde-setl” [that was war seat (saddle)]

- in line 1075 “Þæt wæs geomuru ides” [that was woeful woman]

- in line 1458 “Þæt wæs an foran” [that was of early times]

- in line 1559 “Þæt wæs wæpna cyst” [that was choicest weapon]

- in line 1594 “Þæt wæs yðgeblond” [that was wave mixture]

- in line 1608 “Þæt wæs wundra sum” [that was wondrous thing]

- in line 1692 “Þæt wæs fremde Þeod” [that was estranged people]

- in line 1812 “Þæt wæs modig secg” [that was bold hero]

- in line 1885 “Þæt wæs an cyning” [that was unequaled king]

- in line 2390 “Þæt wæs god cyning” [that was good king]

- in line 2441 “Þæt wæs feohleas gefeoht” [that was fee-less fight (no wergild could be claimed)]

- in line 2817 “Þæt wæs Þam gomelan” [that was last word]

Another formula is “X maÞelode [X spoke].

- in line 348 “Wulfgar maÞelode” [Wulfgar spoke]

- in line 371 “Hroðgar maÞelode” [ Hrothgar spoke]

- in line 405 “Beowulf maÞelode” [Beowulf spoke]

The idea of the formula is that the scop could remember the list of set phrases to remind him of various events in the plot which he needed to tell. Think of telling a children’s story such as “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.” No one uses exactly the same words each time the story is told. However, we all remember the formula: “This X is just right!” And we remember the variation of the formula: this porridge, this chair, this bed, and thus we remember the main events of the plot that need to be told. The formula worked the same way for the Anglo-Saxon scop.

Names to Know From Beowulf

The names from Beowulf are unusual and hard to remember; use the following list to identify major characters in the poem.

- Hrothgar—King whose hall is attacked by Grendel

- Grendel—monster

- Hygelac—Beowulf’s king

- Ecgtheow—Beowulf’s father

- Healfdene—Hrothgar’s father

- Hrethel—Beowulf’s grandfather and Hygelac’s father

- Unferth—character vexed by Beowulf

- Breca—character with whom Beowulf contended in the sea

- Wealhtheow—Hrothgar’s wife

- Aeschere—Hrothgar’s thane killed by Grendel’s mother

- Wiglaf—Beowulf’s faithful thane

- Scyldings—Hrothgar’s people

- Geats—Beowulf’s people

- Heorot—Hrothgar’s hall

- Hrunting—sword given to Beowulf by Unferth

Literary Techniques

-

Old English verses are divided into two half lines with a pause in the middle of the line. The cæsurathe pause in the middle of a line of Old English poetry, the pause in the middle of a line of Old English poetry, is indicated in print by the space in the middle of each line:

line 1 Hwæt! wē Gār-Dena in geār-dagum line 2 Þēod-cyninga Þrym gefrūnon, line 3 hū Þā æðelingas ellen fremedon. line 4 Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaðena Þrēatum, line 5 monegum mǣgðum meodo-setla oftēah. line 6 Egsode eorl, syððan ǣrest wearð line 7 fēa-sceaft funden: hē Þæs frōfre gebād, line 8 wēox under wolcnum, weorð-myndum ðāh, line 9 oð Þæt him ǣghwylc Þāra ymb-sittendra line 10 ofer hron-rāde hȳran scolde, line 11 gomban gyldan: Þæt wæs gōd cyning! -

alliteration

Old English poetry does not use rhyme. Instead, it uses alliterationthe repetition of initial sounds of words in a line of poetry, the repetition of initial sounds of words in a line of poetry. For example, note the repetition of initial “s” sounds in line 4 above and the repetition of initial “m” sounds in line 5.

-

kennings

Old English poetry is characterized by the use of kenningsa compound metaphor used in place of a simple noun, compound metaphors used in place of a simple noun. Examples include whale’s way or swan’s road for ocean, heaven’s candle for the sun, battle sweat for blood, and ring-giver for king.

-

litotes

Old English poetry sometimes expresses ideas with the use of litotesa type of understatement in which meaning is expressed by negating its opposite, a type of understatement in which meaning is expressed by negating its opposite. For example, litotes may be found in the “that was X Y” formula in statements such as “That was not a good place” to mean it was a bad place.

Key Takeaways

- Beowulf is probably about 1000 years old although the dates of its composition and its recording in writing are unknown.

- Beowulf probably was part of the oral tradition for a long period of time before it was recorded in writing.

- Beowulf depicts the Germanic heroic ideal and the king-retainer relationship typical of Anglo-Saxon society.

- Beowulf uses literary techniques typical of Old English poetry such as the caesura, alliteration, kennings, and litotes.

Exercises

- The Germanic heroic ideal was an important standard of behavior and of judging the worth of a leader among the Anglo-Saxons. Locate passages in Beowulf that illustrate the heroic ideal. For example, physical strength is an important quality of a hero; point out specific incidents in Beowulf that illustrate strength.

- The king-retainer relationship formed the basis of Anglo-Saxon society. Locate passages in Beowulf that illustrate this reciprocal relationship. For example, loyalty to one’s leader was an important quality; find specific incidents that illustrate loyalty (or a failure to be loyal).

- One of the curious features of Beowulf is its blend of pagan and Christian allusions. Scholars long believed that the poem was composed by a pagan society but recorded in writing by a monk who added Christian references. Current scholarly opinion is that the poem, which may have had its origins in a pagan society, was composed by Anglo-Saxons who already had been exposed to Christianity after St. Augustine’s efforts beginning in 597. Locate examples of pagan and of Christian references in Beowulf. For example, a reference to fate would be typical of pagan beliefs. Any mention of God or Biblical allusions would be Christian references.

- Old English literature uses literary devices such as epithets, alliteration, kennings, and litotes. Find examples of each of these techniques in Beowulf.

- In addition to the formulas, the Anglo-Saxon scop used a pattern of motifs (recurring images or actions in a literary work) to remember the long, complicated stories which he sang. Find examples of motifs such as beots (boasts), sword failings, gift-giving, and revenge which are repeated in Beowulf.

Boasting, for example, would likely be considered an unattractive trait in our society. However, in the Anglo-Saxon culture, the beot served two important functions. First, it became a type of vow. When Beowulf boasted to Unferth about his exploits in the swimming match against Breca, he not only established himself as a hero with the physical strength and cunning to defeat Grendel, he obligated himself to fight Grendel to the death. He also helped insure his own immortality by making his deeds the subject of legends that would be told by scops long after his death.

Sword failings parallel the degree of loyalty of retainers and become a means to trace the theme of loyalty through the various battles that comprise the plot of Beowulf.

Gift-giving and revenge are essential components of the Anglo-Saxon king-retainer relationship, and they too become a means to trace the plot and theme.

Resources

Text

- Beowulf. Clarence Griffin Child. In Parentheses. Old English Series. York University, Canada. Modern English prose translation.

- Beowulf. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf Gummere translation. Project Gutenberg. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf Old English text. Project Gutenberg.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Gummere’s Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Klaeber’s Old English edition.

- Beowulf in Hypertext. Dr. Anne Savage. McMaster University. Old English and modern English texts.

Audio

Audio in Old English

- “Anglo-Saxon Aloud.” Professory Michael D. C. Drout. Wheaton College.

- “Beowulf.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “Readings from Beowulf.” Old English at the University of Virginia. Peter S. Baker. University of Virginia.

Video

- “Sutton Hoo and Beowulf.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Beowulf manuscript

- “What Is Beowulf?” Julian Harrison, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts. British Library.

- video, print, image of manuscript, podcast.

Anglo-Saxon Culture

- “Anglo-Saxons.” Ancient History In-Depth. BBC.

- “English and Norman Society.” Dr. Mike Ibeji. History In-Depth. BBC. Differences between Anglo-Saxon (Beowulf) and Anglo-Norman culture (Chaucer).

- Excavations at Sutton Hoo. British Museum. Articles about Anglo-Saxon culture as evidenced by findings at Sutton Hoo and links to images of objects in the British Museum.

- Middle Ages. Annenberg Media Learner.org.

- The Sutton Hoo Society. Information about the archaeology of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, an interactive tour of the excavation site, and a picture gallery.

Anglo-Saxon Language

- The Electronic Introduction to Old English. Peter S. Baker. Chapter 1: The Anglo-Saxons and Their Language.

- Modern English to Old English Vocabulary. Memorial University, Canada.

Anglo-Saxon Poetics

- Beowulf: Language and Poetics Quick Reference Sheet. Read, Write, Think (International Reading Association and National Council of Teachers of English).

- The Electronic Introduction to Old English. Peter S. Baker. Chapters 13 and 14.

- Literary Guide: Beowulf. Read, Write, Think (International Reading Association and National Council of Teachers of English). Interactive slide presentation on Beowulf, the story, language, translations, and poetics; designed for high school students.

- “What Is Beowulf?” Julian Harrison, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, British Museum.

- Video, print, image of manuscript, podcast.

Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Bosworth and Toller.

- Modern English to Old English Vocabulary. Memorial University, Canada.