This is “Beowulf”, section 1.4 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.4 Beowulf

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Trace the history of the Beowulf manuscript.

- Interpret theories of structure and theme in Beowulf.

- Define the oral formulaic tradition and give examples of its use in Beowulf.

- Identify major characters and settings in Beowulf.

- List literary techniques typical of Old English poetry, including Beowulf, and provide examples.

Beowulf is the oldest epic poem written in English and is probably the most important extant Old English literary work. It exists in only one manuscript, the Nowell Codex of the British Library MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv. Julian Harrison, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, British Library, provides a comprehensive introduction to Beowulf in “What Is Beowulf?”

Text

- Beowulf. Clarence Griffin Child. In Parentheses. Old English Series. York University, Canada. Modern English prose translation.

- Beowulf. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Gummere translation. Project Gutenberg. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Old English text. Project Gutenberg.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Gummere’s Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Klaeber’s Old English edition.

- Beowulf in Hypertext. Dr. Anne Savage. McMaster University. Old English and modern English texts.

Audio in Old English

- “Anglo-Saxon Aloud.” Professor Michael D. C. Drout. Wheaton College.

- “Beowulf.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “Readings from Beowulf.” Old English at the University of Virginia. Peter S. Baker. University of Virginia.

Composition

Although the events in the poem take place in the 5th century, the poem was likely composed somewhere from the 8th century to the early 11th century. No one, however, knows exactly when the poem was composed or who composed it. It is also possible that the poem had existed through generations as an oral work.

Subject

Although Beowulf is considered the first great English poem, the events are set in what is now Scandinavia. Beowulf and his people, the Geats, are from an area that is now part of Sweden; Hrothgar is king of the Danes. The culture portrayed, however, is the Anglo-Saxon culture using the language brought to Britain beginning with the 5th-century Anglo-Saxon invasions. View a video about the Sutton Hoo ship burial, an archaeological source of much information about the culture portrayed in Beowulf.

Structure

Some scholars see Beowulf as having a two-part structure:

- Beowulf in his prime, fighting Grendel and his mother for the Danes

- Beowulf in old age, fighting the dragon for his own people, the Geats

Other scholars see the structure as corresponding to the three battles:

- Beowulf against Grendel

- Beowulf against Grendel’s mother

- Beowulf against the dragon

Theme

One theme of Beowulf involves the preservation of the Anglo-Saxon societal structure. Every society worries that their values and standards will be abandoned and that their social order will die out as a result. An elegiac tone and a mood of longing for the past permeates the epic Beowulf. At the end of the poem, Wiglaf mourns both the death of Beowulf and the potential passing of his tribe, vulnerable to attack because their reputation for cowardice will spread among other tribes after the retainers fail in their vows of loyalty.

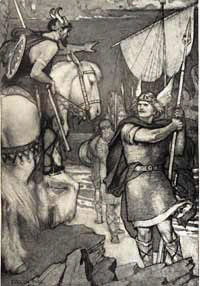

Beowulf challenged by the coast guard by Evelyn Paul, from Guerber’s Myths & Legends of the Middle Ages (1911).

Anglo-Saxon society was based on the Germanic heroic idealthe standard of excellence required of a leader, excellence in all that was important to the tribe: hunting, sea-faring, fighting, the standard of excellence required of a leader, excellence in all that was important to the tribe: hunting, sea-faring, fighting. The leader of each tribal unit, often family units especially in earlier years, gained his position because of his physical strength and capabilities in the activities necessary for survival. The men of the tribe, the thanes or retainers, swore loyalty to the leader and in return he rewarded them with the spoils of their battles and raids.

An important part of the Germanic heroic ideal was the king-retainer relationshipa reciprocal relationship which dictated that the thanes should be loyal to their leader and in return the leader would protect them and share the treasures obtained in battle with them, a reciprocal relationship which dictated that the thanes should be loyal to their leader and in return the leader would protect them and share the treasures obtained in battle with them. The group bound by this relationship, the comitatus, formed the basis of Anglo-Saxon society.

Theme and 3-Part Structure

The theme of concern for cultural values, in this case the comitatus, plays out in the details of the three battles:

- first battle: Beowulf has the “home field” advantage because he fights with Grendel in the mead hall, and he defeats the monster with his bare hands. During the fight, his retainers and Hrothgar’s retainers all stand close by in case Beowulf needs help. They won’t interfere unless Beowulf needs them because they don’t want to detract from their leader’s glory in battle.

- second battle: Beowulf has to go into the monster’s home territory to fight Grendel’s mother, and he has to use a sword—which suggests his strength isn’t quite as great. Not only does Beowulf use Hrunting, the sword Unferth presented him, but when Hrunting fails, Beowulf finds an enormous sword, a sword made by giants (perhaps an ancient Roman sword) which he uses to kill Grendel’s mother. When they see the blood bubbling up through the mere, Hrothgar’s retainers are not faithful—they give up and go home, assuming Beowulf is dead. Only Beowulf’s personal retainers stay at the mere until he returns. There seems to be a direct connection between the loyalty of the retainers and Beowulf’s strength.

- third battle: Fifty years later Beowulf fights the dragon in its lair. All the retainers except Wiglaf abandon their leader and run to hide in the woods. Beowulf not only has to use a weapon to kill the dragon, but he also has to have help from Wiglaf. Again Beowulf’s strength fades as his retainers fail in loyalty.

Notice the speeches that Wiglaf makes to the cowardly retainers. He shames them for running, and he even tells them that now their society will fall. Other tribes will hear about how cowardly they are and, believing them to be easy targets, will come to attack them. The three battles, then, form the structure of the poem and suggest the theme of failing values.

Oral Formulaic Tradition

Many scholars believe that the story of Beowulf existed in oral tradition, perhaps for hundreds of years, before it was recorded in writing, the story told around the fires of the mead hall by the scopthe singer, the shaper or creator of tales, the singer, the shaper or creator of tales. The scop may have used certain memory aids to help him remember the long story, one of which was the formulaa set pattern of words, a set pattern of words. For example: “Þæt wæs god cyning” in line 11 (line numbers may differ according to the translation consulted) of the Prologue uses the formula “Þæt wæs X Y.” The X and Y are filled in with different words each time the formula is used.

- in line 11, “Þæt wæs god cyning” [that was good king]

- in line 170, “Þæt wæs wræc micel” [that was much misery]

- in line 309 “Þæt wæs foremærost” [that was most famous {hall}]

- in line 348 “Þæt wæs Wendla leod” [that was the Wendles’ (Vandals’) chieftain]

- in line 705 “Þæt wæs yldum cuÞ“ [that was widely known]

- in line 765 “Þæt wæs geocor sið“ [that was terrible journey]

- in line 834 “Þæt wæs tacen sweotol” [that was clear symbol]

- in line 864 “Þæt wæs god cyning” [that was good king]

- in line 1039 “Þæt wæs hilde-setl” [that was war seat (saddle)]

- in line 1075 “Þæt wæs geomuru ides” [that was woeful woman]

- in line 1458 “Þæt wæs an foran” [that was of early times]

- in line 1559 “Þæt wæs wæpna cyst” [that was choicest weapon]

- in line 1594 “Þæt wæs yðgeblond” [that was wave mixture]

- in line 1608 “Þæt wæs wundra sum” [that was wondrous thing]

- in line 1692 “Þæt wæs fremde Þeod” [that was estranged people]

- in line 1812 “Þæt wæs modig secg” [that was bold hero]

- in line 1885 “Þæt wæs an cyning” [that was unequaled king]

- in line 2390 “Þæt wæs god cyning” [that was good king]

- in line 2441 “Þæt wæs feohleas gefeoht” [that was fee-less fight (no wergild could be claimed)]

- in line 2817 “Þæt wæs Þam gomelan” [that was last word]

Another formula is “X maÞelode [X spoke].

- in line 348 “Wulfgar maÞelode” [Wulfgar spoke]

- in line 371 “Hroðgar maÞelode” [ Hrothgar spoke]

- in line 405 “Beowulf maÞelode” [Beowulf spoke]

The idea of the formula is that the scop could remember the list of set phrases to remind him of various events in the plot which he needed to tell. Think of telling a children’s story such as “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.” No one uses exactly the same words each time the story is told. However, we all remember the formula: “This X is just right!” And we remember the variation of the formula: this porridge, this chair, this bed, and thus we remember the main events of the plot that need to be told. The formula worked the same way for the Anglo-Saxon scop.

Names to Know From Beowulf

The names from Beowulf are unusual and hard to remember; use the following list to identify major characters in the poem.

- Hrothgar—King whose hall is attacked by Grendel

- Grendel—monster

- Hygelac—Beowulf’s king

- Ecgtheow—Beowulf’s father

- Healfdene—Hrothgar’s father

- Hrethel—Beowulf’s grandfather and Hygelac’s father

- Unferth—character vexed by Beowulf

- Breca—character with whom Beowulf contended in the sea

- Wealhtheow—Hrothgar’s wife

- Aeschere—Hrothgar’s thane killed by Grendel’s mother

- Wiglaf—Beowulf’s faithful thane

- Scyldings—Hrothgar’s people

- Geats—Beowulf’s people

- Heorot—Hrothgar’s hall

- Hrunting—sword given to Beowulf by Unferth

Literary Techniques

-

Old English verses are divided into two half lines with a pause in the middle of the line. The cæsurathe pause in the middle of a line of Old English poetry, the pause in the middle of a line of Old English poetry, is indicated in print by the space in the middle of each line:

line 1 Hwæt! wē Gār-Dena in geār-dagum line 2 Þēod-cyninga Þrym gefrūnon, line 3 hū Þā æðelingas ellen fremedon. line 4 Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaðena Þrēatum, line 5 monegum mǣgðum meodo-setla oftēah. line 6 Egsode eorl, syððan ǣrest wearð line 7 fēa-sceaft funden: hē Þæs frōfre gebād, line 8 wēox under wolcnum, weorð-myndum ðāh, line 9 oð Þæt him ǣghwylc Þāra ymb-sittendra line 10 ofer hron-rāde hȳran scolde, line 11 gomban gyldan: Þæt wæs gōd cyning! -

alliteration

Old English poetry does not use rhyme. Instead, it uses alliterationthe repetition of initial sounds of words in a line of poetry, the repetition of initial sounds of words in a line of poetry. For example, note the repetition of initial “s” sounds in line 4 above and the repetition of initial “m” sounds in line 5.

-

kennings

Old English poetry is characterized by the use of kenningsa compound metaphor used in place of a simple noun, compound metaphors used in place of a simple noun. Examples include whale’s way or swan’s road for ocean, heaven’s candle for the sun, battle sweat for blood, and ring-giver for king.

-

litotes

Old English poetry sometimes expresses ideas with the use of litotesa type of understatement in which meaning is expressed by negating its opposite, a type of understatement in which meaning is expressed by negating its opposite. For example, litotes may be found in the “that was X Y” formula in statements such as “That was not a good place” to mean it was a bad place.

Key Takeaways

- Beowulf is probably about 1000 years old although the dates of its composition and its recording in writing are unknown.

- Beowulf probably was part of the oral tradition for a long period of time before it was recorded in writing.

- Beowulf depicts the Germanic heroic ideal and the king-retainer relationship typical of Anglo-Saxon society.

- Beowulf uses literary techniques typical of Old English poetry such as the caesura, alliteration, kennings, and litotes.

Exercises

- The Germanic heroic ideal was an important standard of behavior and of judging the worth of a leader among the Anglo-Saxons. Locate passages in Beowulf that illustrate the heroic ideal. For example, physical strength is an important quality of a hero; point out specific incidents in Beowulf that illustrate strength.

- The king-retainer relationship formed the basis of Anglo-Saxon society. Locate passages in Beowulf that illustrate this reciprocal relationship. For example, loyalty to one’s leader was an important quality; find specific incidents that illustrate loyalty (or a failure to be loyal).

- One of the curious features of Beowulf is its blend of pagan and Christian allusions. Scholars long believed that the poem was composed by a pagan society but recorded in writing by a monk who added Christian references. Current scholarly opinion is that the poem, which may have had its origins in a pagan society, was composed by Anglo-Saxons who already had been exposed to Christianity after St. Augustine’s efforts beginning in 597. Locate examples of pagan and of Christian references in Beowulf. For example, a reference to fate would be typical of pagan beliefs. Any mention of God or Biblical allusions would be Christian references.

- Old English literature uses literary devices such as epithets, alliteration, kennings, and litotes. Find examples of each of these techniques in Beowulf.

- In addition to the formulas, the Anglo-Saxon scop used a pattern of motifs (recurring images or actions in a literary work) to remember the long, complicated stories which he sang. Find examples of motifs such as beots (boasts), sword failings, gift-giving, and revenge which are repeated in Beowulf.

Boasting, for example, would likely be considered an unattractive trait in our society. However, in the Anglo-Saxon culture, the beot served two important functions. First, it became a type of vow. When Beowulf boasted to Unferth about his exploits in the swimming match against Breca, he not only established himself as a hero with the physical strength and cunning to defeat Grendel, he obligated himself to fight Grendel to the death. He also helped insure his own immortality by making his deeds the subject of legends that would be told by scops long after his death.

Sword failings parallel the degree of loyalty of retainers and become a means to trace the theme of loyalty through the various battles that comprise the plot of Beowulf.

Gift-giving and revenge are essential components of the Anglo-Saxon king-retainer relationship, and they too become a means to trace the plot and theme.

Resources

Text

- Beowulf. Clarence Griffin Child. In Parentheses. Old English Series. York University, Canada. Modern English prose translation.

- Beowulf. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf Gummere translation. Project Gutenberg. Modern English translation.

- Beowulf Old English text. Project Gutenberg.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Gummere’s Modern English translation.

- Beowulf. Paul Halsall. Fordham University. ORB Medieval Sourcebook. Klaeber’s Old English edition.

- Beowulf in Hypertext. Dr. Anne Savage. McMaster University. Old English and modern English texts.

Audio

Audio in Old English

- “Anglo-Saxon Aloud.” Professory Michael D. C. Drout. Wheaton College.

- “Beowulf.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “Readings from Beowulf.” Old English at the University of Virginia. Peter S. Baker. University of Virginia.

Video

- “Sutton Hoo and Beowulf.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Beowulf manuscript

- “What Is Beowulf?” Julian Harrison, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts. British Library.

- video, print, image of manuscript, podcast.

Anglo-Saxon Culture

- “Anglo-Saxons.” Ancient History In-Depth. BBC.

- “English and Norman Society.” Dr. Mike Ibeji. History In-Depth. BBC. Differences between Anglo-Saxon (Beowulf) and Anglo-Norman culture (Chaucer).

- Excavations at Sutton Hoo. British Museum. Articles about Anglo-Saxon culture as evidenced by findings at Sutton Hoo and links to images of objects in the British Museum.

- Middle Ages. Annenberg Media Learner.org.

- The Sutton Hoo Society. Information about the archaeology of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, an interactive tour of the excavation site, and a picture gallery.

Anglo-Saxon Language

- The Electronic Introduction to Old English. Peter S. Baker. Chapter 1: The Anglo-Saxons and Their Language.

- Modern English to Old English Vocabulary. Memorial University, Canada.

Anglo-Saxon Poetics

- Beowulf: Language and Poetics Quick Reference Sheet. Read, Write, Think (International Reading Association and National Council of Teachers of English).

- The Electronic Introduction to Old English. Peter S. Baker. Chapters 13 and 14.

- Literary Guide: Beowulf. Read, Write, Think (International Reading Association and National Council of Teachers of English). Interactive slide presentation on Beowulf, the story, language, translations, and poetics; designed for high school students.

- “What Is Beowulf?” Julian Harrison, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, British Museum.

- Video, print, image of manuscript, podcast.

Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Bosworth and Toller.

- Modern English to Old English Vocabulary. Memorial University, Canada.