This is “Hearing”, section 4.3 from the book Beginning Psychology (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.3 Hearing

Learning Objectives

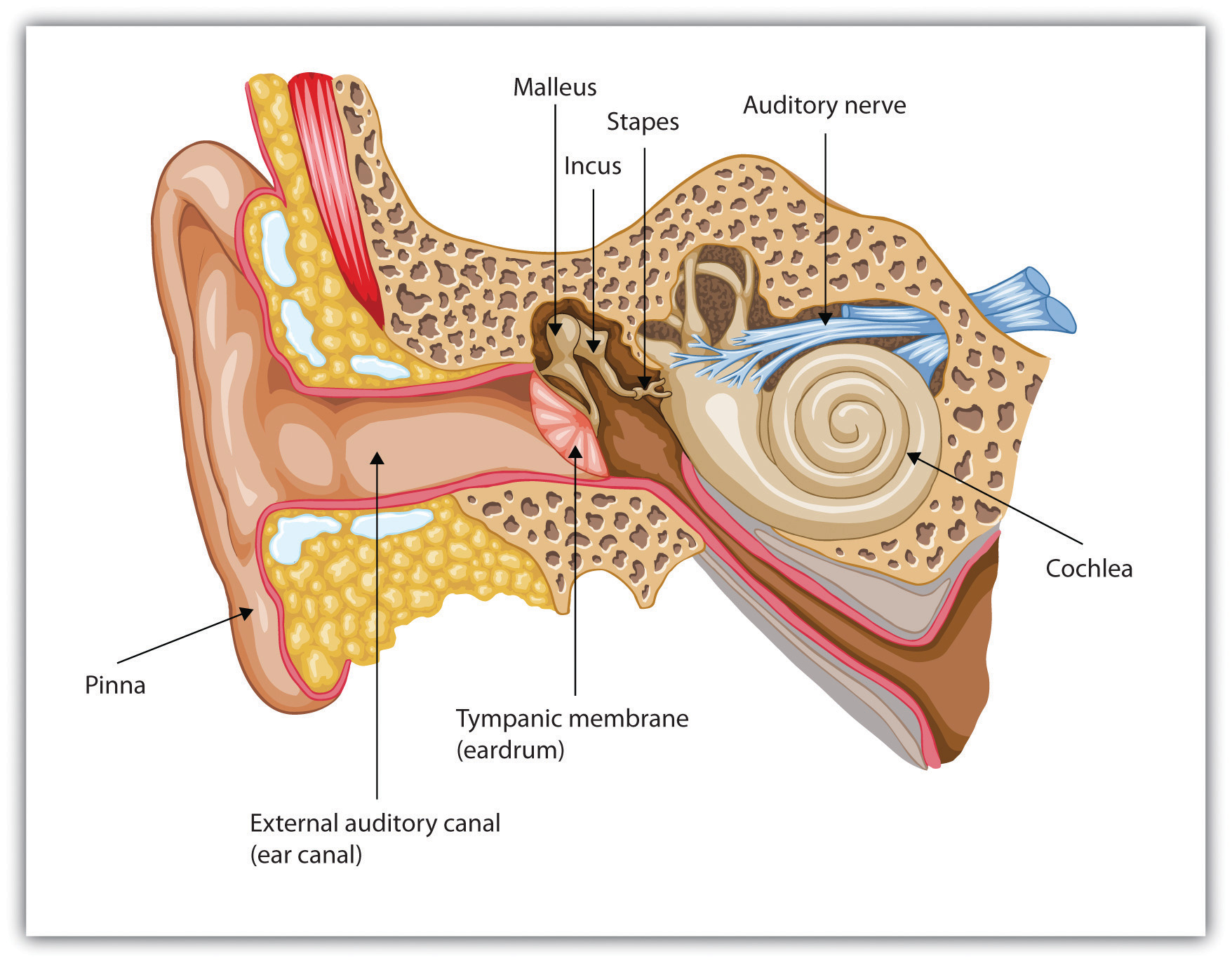

- Draw a picture of the ear and label its key structures and functions, and describe the role they play in hearing.

- Describe the process of transduction in hearing.

Like vision and all the other senses, hearing begins with transduction. Sound waves that are collected by our ears are converted into neural impulses, which are sent to the brain where they are integrated with past experience and interpreted as the sounds we experience. The human ear is sensitive to a wide range of sounds, ranging from the faint tick of a clock in a nearby room to the roar of a rock band at a nightclub, and we have the ability to detect very small variations in sound. But the ear is particularly sensitive to sounds in the same frequency as the human voice. A mother can pick out her child’s voice from a host of others, and when we pick up the phone we quickly recognize a familiar voice. In a fraction of a second, our auditory system receives the sound waves, transmits them to the auditory cortex, compares them to stored knowledge of other voices, and identifies the identity of the caller.

The Ear

Just as the eye detects light waves, the ear detects sound waves. Vibrating objects (such as the human vocal chords or guitar strings) cause air molecules to bump into each other and produce sound waves, which travel from their source as peaks and valleys much like the ripples that expand outward when a stone is tossed into a pond. Unlike light waves, which can travel in a vacuum, sound waves are carried within mediums such as air, water, or metal, and it is the changes in pressure associated with these mediums that the ear detects.

As with light waves, we detect both the wavelength and the amplitude of sound waves. The wavelength of the sound wave (known as frequencyThe wavelength of a sound wave.) is measured in terms of the number of waves that arrive per second and determines our perception of pitchThe perceived frequency of a sound., the perceived frequency of a sound. Longer sound waves have lower frequency and produce a lower pitch, whereas shorter waves have higher frequency and a higher pitch.

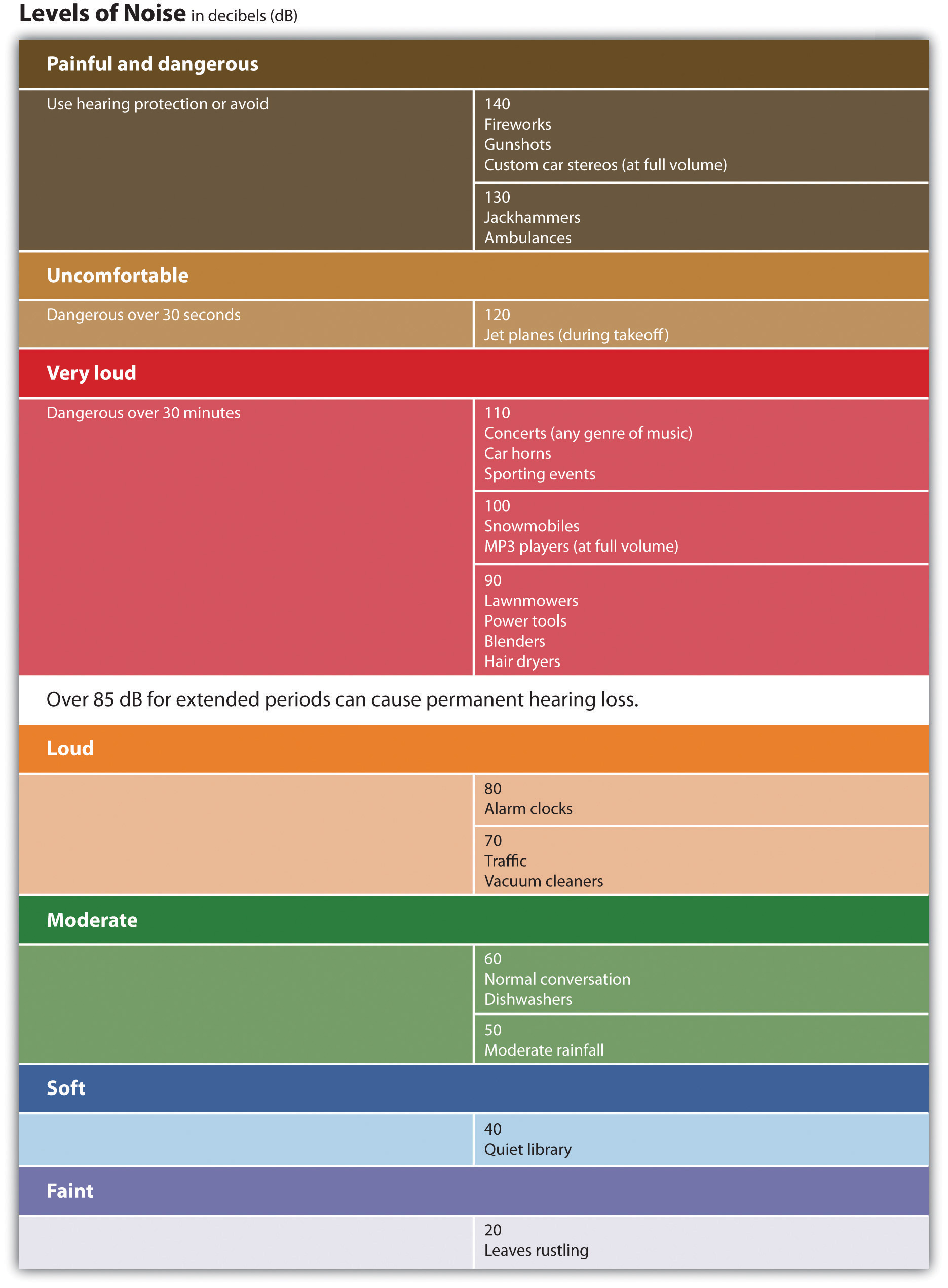

The amplitudeThe height of a sound wave., or height of the sound wave, determines how much energy it contains and is perceived as loudnessThe degree of sound volume. (the degree of sound volume). Larger waves are perceived as louder. Loudness is measured using the unit of relative loudness known as the decibelThe unit of relative loudness.. Zero decibels represent the absolute threshold for human hearing, below which we cannot hear a sound. Each increase in 10 decibels represents a tenfold increase in the loudness of the sound (see Figure 4.29 "Sounds in Everyday Life"). The sound of a typical conversation (about 60 decibels) is 1,000 times louder than the sound of a faint whisper (30 decibels), whereas the sound of a jackhammer (130 decibels) is 10 billion times louder than the whisper.

Figure 4.29 Sounds in Everyday Life

The human ear can comfortably hear sounds up to 80 decibels. Prolonged exposure to sounds above 80 decibels can cause hearing loss.

Audition begins in the pinnaThe external and v isible part of the ear., the external and visible part of the ear, which is shaped like a funnel to draw in sound waves and guide them into the auditory canal. At the end of the canal, the sound waves strike the tightly stretched, highly sensitive membrane known as the tympanic membrane (or eardrum)The membrane at the end of the ear canal that relays vibrations into the middle ear., which vibrates with the waves. The resulting vibrations are relayed into the middle ear through three tiny bones, known as the ossiclesThe three tiny bones in the ear (hammer, anvil, and stirrup) that relay sound from the eardrum to the cochlea.—the hammer (or malleus), anvil (or incus), and stirrup (or stapes)—to the cochleaA snail-shaped liquid-filled tube in the inner ear that contains the cilia., a snail-shaped liquid-filled tube in the inner ear. The vibrations cause the oval windowThe membrane covering the opening of the cochlea., the membrane covering the opening of the cochlea, to vibrate, disturbing the fluid inside the cochlea.

The movements of the fluid in the cochlea bend the hair cells of the inner ear, much in the same way that a gust of wind bends over wheat stalks in a field. The movements of the hair cells trigger nerve impulses in the attached neurons, which are sent to the auditory nerve and then to the auditory cortex in the brain. The cochlea contains about 16,000 hair cells, each of which holds a bundle of fibers known as cilia on its tip. The cilia are so sensitive that they can detect a movement that pushes them the width of a single atom. To put things in perspective, cilia swaying at the width of an atom is equivalent to the tip of the Eiffel Tower swaying by half an inch (Corey et al., 2004).Corey, D. P., García-Añoveros, J., Holt, J. R., Kwan, K. Y., Lin, S.-Y., Vollrath, M. A., Amalfitano, A.,…Zhang, D.-S. (2004). TRPA1 is a candidate for the mechano-sensitive transduction channel of vertebrate hair cells. Nature, 432, 723–730. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v432/n7018/full/nature03066.html

Figure 4.30 The Human Ear

Sound waves enter the outer ear and are transmitted through the auditory canal to the eardrum. The resulting vibrations are moved by the three small ossicles into the cochlea, where they are detected by hair cells and sent to the auditory nerve.

Although loudness is directly determined by the number of hair cells that are vibrating, two different mechanisms are used to detect pitch. The frequency theory of hearingA theory of pitch perception that proposes that nerve impulses corresponding to the pitch of a sound are sent to the auditory nerve. proposes that whatever the pitch of a sound wave, nerve impulses of a corresponding frequency will be sent to the auditory nerve. For example, a tone measuring 600 hertz will be transduced into 600 nerve impulses a second. This theory has a problem with high-pitched sounds, however, because the neurons cannot fire fast enough. To reach the necessary speed, the neurons work together in a sort of volley system in which different neurons fire in sequence, allowing us to detect sounds up to about 4,000 hertz.

Not only is frequency important, but location is critical as well. The cochlea relays information about the specific area, or place, in the cochlea that is most activated by the incoming sound. The place theory of hearingA theory of pitch perception that proposes that different areas of the cochlea respond to different sound frequencies. proposes that different areas of the cochlea respond to different frequencies. Higher tones excite areas closest to the opening of the cochlea (near the oval window). Lower tones excite areas near the narrow tip of the cochlea, at the opposite end. Pitch is therefore determined in part by the area of the cochlea firing the most frequently.

Just as having two eyes in slightly different positions allows us to perceive depth, so the fact that the ears are placed on either side of the head enables us to benefit from stereophonic, or three-dimensional, hearing. If a sound occurs on your left side, the left ear will receive the sound slightly sooner than the right ear, and the sound it receives will be more intense, allowing you to quickly determine the location of the sound. Although the distance between our two ears is only about 6 inches, and sound waves travel at 750 miles an hour, the time and intensity differences are easily detected (Middlebrooks & Green, 1991).Middlebrooks, J. C., & Green, D. M. (1991). Sound localization by human listeners. Annual Review of Psychology, 42, 135–159. When a sound is equidistant from both ears, such as when it is directly in front, behind, beneath or overhead, we have more difficulty pinpointing its location. It is for this reason that dogs (and people, too) tend to cock their heads when trying to pinpoint a sound, so that the ears receive slightly different signals.

Hearing Loss

More than 31 million Americans suffer from some kind of hearing impairment (Kochkin, 2005).Kochkin, S. (2005). MarkeTrak VII: Hearing loss population tops 31 million people. Hearing Review, 12(7) 16–29. Conductive hearing loss is caused by physical damage to the ear (such as to the eardrums or ossicles) that reduce the ability of the ear to transfer vibrations from the outer ear to the inner ear. Sensorineural hearing loss, which is caused by damage to the cilia or to the auditory nerve, is less common overall but frequently occurs with age (Tennesen, 2007).Tennesen, M. (2007, March 10). Gone today, hear tomorrow. New Scientist, 2594, 42–45. The cilia are extremely fragile, and by the time we are 65 years old, we will have lost 40% of them, particularly those that respond to high-pitched sounds (Chisolm, Willott, & Lister, 2003).Chisolm, T. H., Willott, J. F., & Lister, J. J. (2003). The aging auditory system: Anatomic and physiologic changes and implications for rehabilitation. International Journal of Audiology, 42(Suppl. 2), 2S3–2S10.

Prolonged exposure to loud sounds will eventually create sensorineural hearing loss as the cilia are damaged by the noise. People who constantly operate noisy machinery without using appropriate ear protection are at high risk of hearing loss, as are people who listen to loud music on their headphones or who engage in noisy hobbies, such as hunting or motorcycling. Sounds that are 85 decibels or more can cause damage to your hearing, particularly if you are exposed to them repeatedly. Sounds of more than 130 decibels are dangerous even if you are exposed to them infrequently. People who experience tinnitus (a ringing or a buzzing sensation) after being exposed to loud sounds have very likely experienced some damage to their cilia. Taking precautions when being exposed to loud sound is important, as cilia do not grow back.

While conductive hearing loss can often be improved through hearing aids that amplify the sound, they are of little help to sensorineural hearing loss. But if the auditory nerve is still intact, a cochlear implant may be used. A cochlear implant is a device made up of a series of electrodes that are placed inside the cochlea. The device serves to bypass the hair cells by stimulating the auditory nerve cells directly. The latest implants utilize place theory, enabling different spots on the implant to respond to different levels of pitch. The cochlear implant can help children hear who would normally be deaf, and if the device is implanted early enough, these children can frequently learn to speak, often as well as normal children do (Dettman, Pinder, Briggs, Dowell, & Leigh, 2007; Dorman & Wilson, 2004).Dettman, S. J., Pinder, D., Briggs, R. J. S., Dowell, R. C., & Leigh, J. R. (2007). Communication development in children who receive the cochlear implant younger than 12 months: Risk versus benefits. Ear and Hearing, 28(2, Suppl.), 11S–18S; Dorman, M. F., & Wilson, B. S. (2004). The design and function of cochlear implants. American Scientist, 92, 436–445.

Key Takeaways

- Sound waves vibrating through mediums such as air, water, or metal are the stimulus energy that is sensed by the ear.

- The hearing system is designed to assess frequency (pitch) and amplitude (loudness).

- Sound waves enter the outer ear (the pinna) and are sent to the eardrum via the auditory canal. The resulting vibrations are relayed by the three ossicles, causing the oval window covering the cochlea to vibrate. The vibrations are detected by the cilia (hair cells) and sent via the auditory nerve to the auditory cortex.

- There are two theories as to how we perceive pitch: The frequency theory of hearing suggests that as a sound wave’s pitch changes, nerve impulses of a corresponding frequency enter the auditory nerve. The place theory of hearing suggests that we hear different pitches because different areas of the cochlea respond to higher and lower pitches.

- Conductive hearing loss is caused by physical damage to the ear or eardrum and may be improved by hearing aids or cochlear implants. Sensorineural hearing loss, caused by damage to the hair cells or auditory nerves in the inner ear, may be produced by prolonged exposure to sounds of more than 85 decibels.

Exercise and Critical Thinking

- Given what you have learned about hearing in this chapter, are you engaging in any activities that might cause long-term hearing loss? If so, how might you change your behavior to reduce the likelihood of suffering damage?