This is “Practices for Making Your Culture More Innovative”, section 10.4 from the book Beginning Organizational Change (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

10.4 Practices for Making Your Culture More Innovative

Similar to previous chapters, we conclude this chapter with a discussion of seven practices that can be used to enhance your organization’s capacity for change in this particular area.

Practice 1: Make Innovation Everyone’s Responsibility

In too many organizations, innovation is assumed to be the responsibility of the top management team, or the research and development unit.Hargadon and Sutton (2000). While these two groups of people are essential, this emphasis will fail to capture the “wisdom of the anthill.”Hamel and Prahalad (1994). Innovation is essentially a collaborative endeavor, where collective imagination yields new business opportunities.Hammer (2004).

According to Peter Drucker, innovation and entrepreneurship are capable of being presented as a discipline. In other words, it can be learned and practiced. Most important for us in this chapter, Drucker asserts that it can be fostered and encouraged throughout an entire organization.Drucker (1996). One of the keys appears to be to create a collaborative, “information-rich” environment in which all employees are invited to contribute.Kanter (2006). Commenting on the success of the Sundance Film Festival, Robert Redford stated, “If you create an atmosphere of freedom, where people aren’t afraid someone will steal their ideas, they will engage with each other, they will help one another, and they will do some amazingly creative things together.”Zades (2003), p. 67.

Practice 2: Hire and Retain Creative Employees

All innovation depends on the generation of new ideas, but no new ideas will be generated in the absence of human creativity. Consequently, the hiring process needs to emphasize the importance of selecting individuals who have creative potential. More importantly, the human resources system needs to focus on developing that creativity and retaining individuals who show creative promise.Mumford (2000).

However, creative individuals aren’t the only ones required to cultivate a more innovative culture. Other individuals, such as “knowledge brokers,” are also essential. Knowledge brokersIndividuals who collect ideas and combine them in unique and valuable ways. They are skilled at cultivating a more innovative organizational culture by keeping new ideas alive. are individuals who constantly collect ideas and combine them in unique and valuable ways. They often are not the originators of the ideas, but they have a skill at keeping new ideas alive and seeing where they lead. Hargadon and Sutton (2000). Sometimes older workers lose their creative spark but serve as knowledge brokers to keep the spark alive.

Most organizations are uncomfortable with “mavericks” who shake up the status quo and display irreverence for accepted wisdom. However, mavericksIndividuals who play a vital role in making an organization more innovative; they are typically independent thinkers who do not embrace the status quo. play a vital role in making an organization more innovative, especially larger organizations.Stringer (2000). For example, Jack Welch, a relatively famous maverick who led General Electric through a very innovative period, stated, “Here at GE, we reward failure.”Farson and Keyes (2002). Indeed, there is scientific research that demonstrates that when the reward system recognizes and retains creative employees, the organization behaves more innovatively.Chandler, Keller, & Lyon (2000).

Practice 3: Put as Many Promising Ideas to the Test as Possible

A popular but controversial mantra in innovative organizations is “fail fast, fail cheap.” The idea here is that it is important to get your new ideas in rough form out into the marketplace, and learn from your customers. This is in contrast to the “go–no go” approach where companies want new ideas to be 95% right before taking any action.Hall (2007). Perhaps this is why IBM’s Thomas Watson, Sr., once said, “The fastest way to succeed is to double your failure rate.”Edmondson (2002), p. 64.

However, fast and cheap are not enough; the innovative organization also needs to learn from the experience in order to make the “failure” pay off. This is where testing comes in. Hence, a key ingredient to becoming more culturally innovative is the importance of designing relatively small-scale, but rigorous tests or “experiments.” For example, Capital One, a highly successful retail bank, was founded on experimental design where new ideas were constantly tested. Tests are most reliable when many roughly equivalent settings can be observed—some containing the new idea and some not.Davenport (2009). Similarly, IDEO, perhaps the most innovative design firm in the world, is a staunch proponent of encouraging experimenters who prototype ideas quickly and cheaply.Kelley and Littman (2005). In sum, innovative cultures fail fast and fail cheap and learn from their failures.

Practice 4: Use Your Human Resources System to Create Psychological Safety

Organizations operate in increasingly competitive environments. The concept of “winning” is an important one, and being labeled a “winner” is usually a key to organizational advancement. Unfortunately, failure is an integral part of innovation, so innovative cultures need to create the psychological safety whereby failure in certain circumstances is acceptable.Edmondson (2008).

Some mistakes are more lethal than others, so mistakes that do not jeopardize the survival of the organization need to be accepted, even welcomed by leaders. Relatedly, it is more important to focus on the ideas rather than the individuals behind the ideas so that failure is not personalized. And “failure-tolerant leaders emphasize that a good idea is a good idea, whether it comes from Peter Drucker, Reader’s Digest, or an obnoxious coworker.”Farson and Keyes (2002), p. 70.

Once again, the human resources system can be instrumental in helping to create the psychological safety to enable innovation. In this case, the system can be designed to permit and even celebrate failure.Bowen and Ostroff (2004). Clearly, this involves a balancing act between rewarding success and tolerating failure. Consequently, the key is to create sufficient psychological safety within a culture so that the organization can “dance on the borderline between success and failure.”Wylie (2001).

Practice 5: Emphasize Interdisciplinary Teams Throughout the Entire Organization

In the 1970s and 1980s, many organizations tried to create specialized subunits where their mandate was to make the organization more innovative. This structural approach to innovation largely failed, either immediately or in the long term. For example, General Motors created the Saturn division as a built-from-scratch innovative new way to produce and sell cars. At first, Saturn had spectacular success. However, the lessons learned from Saturn never translated to the rest of the organization and recently the Saturn division was eliminated.Hanna (2010). Similarly, too many large organizations try to rely solely on their research and development units for innovation, which greatly constrains the idea production and development process.Stringer (2000).

Innovation is clearly a team sport, one that should pervade the entire organization. As a result, ad hoc interdisciplinary teams appear to be the proper structural approach to fostering innovation. Today, IDEO is one of the most innovative firms in the world, and their approach to business is centered around interdisciplinary teams.Kelley and Littman (2005). In sum, the ad hoc interdisciplinary team appears to be the structural solution to innovation, not a self-contained innovative subunit as some suggest.

Practice 6: Change Cultural Artifacts and Values to Signal Importance of Innovation

Recall from the previous chapter that one key way to change a culture is to intentionally shift the cultural artifacts in the direction of the desired change. When creativity and innovation is desired, it is important to be more flexible in the work environment. So flexibility in working arrangements, dress codes, and organizational titles becomes important.

New myths and rituals are required that focus on creativity and innovation. For example, some organizations celebrate failed experiments based on imaginative new ideas. Other organizations promote individuals who took a risk on a promising new idea that did not work out. And changing the formal values statement to incorporate an explicit statement about creativity and innovation highlights its new importance. Still others change the metaphors used in the organization. For example, creating a “blank canvas” culture evokes an image of artists operating without artificial constraints.

Fundamentally, cultures are not changed by new thoughts or words, they are changed by new behaviors that reinforce the cultural attributes that are desired. For example, GM’s automobile plant in Fremont, California, transformed its culture by adopting the lean manufacturing behaviors advocated by its new venture partner, Toyota Motors. For example, nothing was as transformative at this particular plant as the “simple” act of empowering frontline employees to stop the productive line at any time due to quality concerns. This new policy had dramatic impacts on the revitalization of this unionized plant.Shook (2010).

Practice 7: Change Cultural Assumptions to Signal Importance of Innovation

Culture change does not occur until the underlying assumptions that pervade the organization are challenged and replaced with some new assumptions. Therefore, ordering new behaviors isn’t enough. The organization must thoughtfully identify what the old assumptions are and work to instill new assumptions that support the culture desired. Consequently, contemplation and reflection are essential to any culture-change initiative. Perhaps this is why Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad note that “true strategy is the result of deep, innovative thinking.”Hamel and Prahalad (1994), p. 56.

Some observers call for “disciplined reflection”;Edmondson (2008). while others urge leaders to identify “constraining assumptions.”Hammer (2004). Whatever the term that is used, organizational members need to think deeply about where their culture limits innovation, and to identify what cultural assumptions are the limiting factor. This requires a collective perspective; very rarely can a single leader come to this realization. Since most organizations have a bias for action, this reflection can be especially difficult. However, organizational learning often requires unlearning old and harmful assumptions and this is especially true for cultivating innovativeness.Senge (1990).

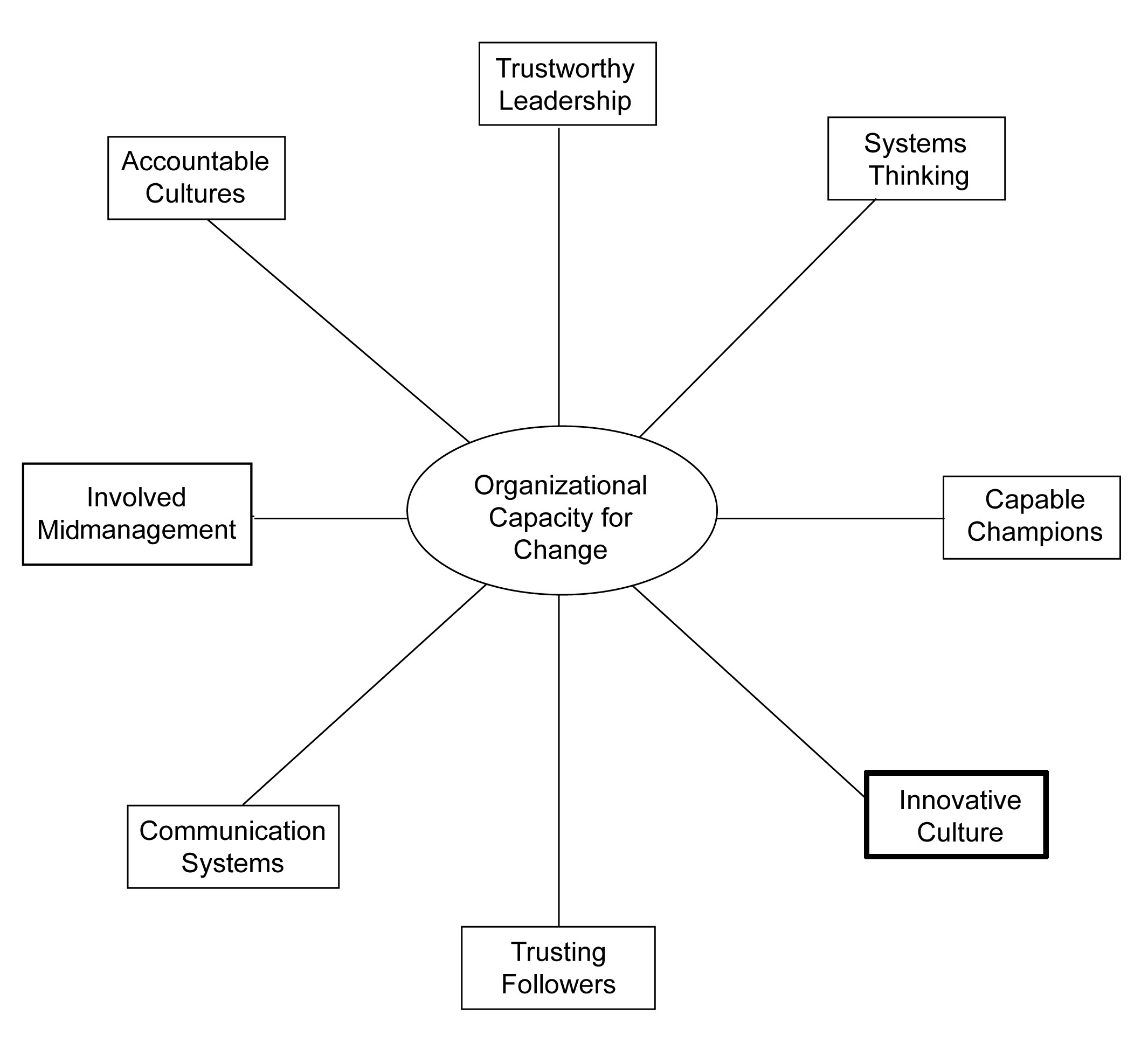

In conclusion, the eighth and final dimension of organizational capacity for change is an innovative culture that fosters and celebrates creativity and innovation. This dimension is an essential counterbalance to accountability systems. Together, these two dimensions complete our understanding of how to make your organization more change capable.

Figure 10.1 The Eighth Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Innovative Culture