This is “OCC Dimension 3: Capable Champions”, chapter 5 from the book Beginning Organizational Change (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 5 OCC Dimension 3: Capable Champions

Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

To be a great champion you must believe you are the best. If you’re not, pretend you are.

Muhammad Ali

Top executives increasingly create cross-functional task forces comprised of respected middle managers to serve as a guiding coalition for major change initiatives. However, even when the top management team personally leads a change initiative, such as in life-or-death turnaround situations, individual change champions within the middle management ranks must “step up” if the change is to be successful. Consequently, the “vertical” chain of command, addressed in the previous two chapters (the hierarchical leader–follower relationship), is not enough to create a change-capable organization. Because organizations are removing layers of bureaucracy and because we are moving from an industrial economy to an information-based economy, “lateral” relationships and leadership are becoming more important. This chapter examines one essential part of that lateral relationship, namely, “capable champions.”

A capable champion is a middle manager who is able to influence others in the organization to adopt a proposed change without the formal authority to do so. In a systematic study of change champions conducted by McKinsey and Company, they found that these middle managers are different from the typical manager. While traditional managers always seek to make their numbers; change champions seek to satisfy customers and coworkers. Traditional managers hold others accountable; change champions hold everyone accountable, including themselves. In addition, traditional managers are fearful of failure; change champions are not afraid of failure and understand that they have career options outside of this job. In sum, traditional managers analyze, leverage, optimize, delegate, organize, and control with the basic mind-set that “I know best.” In contrast, change champions’ basic mind-set is to do it, fix it, change it, and that no one person knows best.Katzenbach (1996).

Clearly, organizations need to be both managed well and led effectively if they are to be successful over time. However, most organizations are overmanaged and underled,Bennis and Nanus (1997). and capable change champions are one of the best antidotes to this organizational imbalance. As Rosabeth Moss Kanter states,

Senior executives can come up with the most brilliant strategy in history, but if the people who design products, talk to customers, and oversee operations don’t foster innovation in their own realms, none of that brilliance will make a whit of difference.Kanter (2004), p. 150.

5.1 Influence Without Authority

Because organization-wide change and innovation frequently goes beyond existing organizational subunits and lines of authority, change champions often need to go beyond their existing authority in order to get things changed. To do this, they need power, which can be thought of as the capacity to mobilize resources and people to get things done. And just as absolute power corrupts, absolute powerlessness on the part of change champions also corrupts in the sense that those who are more interested in turf protection than in the overall organization are not challenged to think and behave in a bigger fashion.Kanter (2004), p. 153.

The advantage the change champions bring to the table is their deep knowledge of how things actually are and how things need to change to make the change vision a reality; the disadvantage that they have is their inadequate power base to influence those with whom they have no authority. Consequently, organizations that are “built to change” hire, retain, and promote change champions in sufficient numbers to counterbalance the equilibrium-seeking rest of the organization. In short, change champions are masters of influencing others without the authority to do so.

The first people change champions need to influence is their superiors and the top management team. Not all middle managers know how to “manage up,” but this talent is essential. There is a phenomenon operating to varying extents in all organizations known as “CEO disease.” This organizational malady is the information vacuum around a senior leader that gets created when people, including his or her inner circle, withhold important information. This leaves the senior leader out of touch and out of tune with the rest of the organization, its environment, or both.Arond-Thomas (2009).

Change champions are adept at selling strategic issues for senior managers to address. Change champions are also courageous enough to challenge senior executives when they are off track or misinformed. And change champions obtain the “sponsorship” of executives to act on the executives’ behalf. All of these behaviors require sophisticated political skills and the character to do this well.

In addition to influencing senior executives, change champions must also influence other middle managers to consider and adopt organizational changes. In this case, informal networks of influence must be created or expanded in order to bring about change, neutralize resistance to change initiatives, or both. One of the key ways that change champions do this is by the creation of alliances through exchanges of currencies.

Allan Cohen and David Bradford have written the seminal book on influence without authority, which is the ability to lead others when you do not have authority over them. These authors argue that many different currencies circulate within organizations, and that money is just one of those currencies. Those non-authority-related currencies include such things as inspiration-related currencies (e.g., vision, moral, or ethical correctness), task-related currencies (e.g., the pledge of new resources, organizational support, or information), relationship-related currencies (e.g., understanding, acceptance, or inclusion), and personal-related currencies (e.g., gratitude, comfort, or enhancement of self-concept).Cohen and Bradford (2005).

In particular, they emphasize the role of negotiations in creating win-win intraorganizational alliances and partnerships. To do so, they argue that you as a change champion must (a) know and communicate what your goals and intentions are to your potential ally, (b) understand your potential ally’s world and what his or her goals and intentions are, and (c) make win-win exchanges that prevent organizational changes from proceeding.Cohen and Bradford (2005).

Finally, change champions must influence frontline workers who are not under their direct supervision if the organization is to become change capable. Whenever change initiatives are launched, there are multiple “narratives” that flow through the organization because communication from the “top” is almost always inadequate, and listening from the “bottom” is often filtered. Change champions help to make sense of those often conflicting narratives so that frontline workers feel less threatened by the changes.Balogun and Johnson (2004).

Similar to other middle managers, change champions, in order to get changes adopted, can also trade currencies with frontline workers over whom they have no authority. Since frontline workers often feel oppressed and ignored within many hierarchical organizations, the softer skills—such as expressing sincere gratitude, including frontline workers in the change process, and understanding and accepting them—are particularly important to change champions if these alliances are to be maintained.

5.2 Getting Things Done When Not in Charge

Geoffrey Bellman is an organizational development consultant who has written a national best seller about being a change champion. In his book, he says that in order to work effectively with other people over whom you have no authority, it is important to start out by being clear about what you want. Specifically, he states, “Clarity about your vision of what you want increases the likelihood you will reach for it.”Bellman (2001), p. 118.

He adds that “when we are not doing what we want to do, we are doing what others want us to do.”Bellman (2001), p. 21. In essence, he argues for the power of an authentic life over the power of organizationally backed authority. One of the implications of such a posture is that becoming a change champion within an organization requires that you be prepared to leave it when or if your life’s purpose cannot be pursued. Bellman states it well: “Worse that losing a job is keeping a job in which you are not respected, or not listened to, or not consulted, or not influential, or…you name it, it is your fear.”Bellman (2001), pp. 110–111.

Similar to other observers, Bellman argues that by keeping the combined interests of yourself and others in mind, you will get things done when not in charge. However, he further adds that many changes and change visions must wait for the proper time to act. In other words, change champions must be politically astute in their timing of change initiatives as they consider the evolving interests of others along with the evolving interests of themselves.

5.3 Rising Importance of Change Champions

Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom used a creative analogy from the animal kingdom to illustrate the rising importance of change champions within organizations. They argued that future organizations will function more like starfish, and less like spiders. They state,

If you chop off a spider’s head, it dies. If you take out the corporate headquarters, chances are you’ll kill the spider organization…Starfish don’t have a head to chop off. Its central body isn’t even in charge. In fact, the major organs are replicated through each and every arm. If you cut the starfish in half, you’ll be in for a surprise: the animal won’t die, and pretty soon you’ll have two starfish to deal with.Brafman and Beckstrom (2006), p. 35.

Illustrating their point, they argue that the organizations of the 21st century, what they call “starfish” organizations, are demonstrated by customer-enabled Internet firms such as eBay, Skype, Kazaa, Craigslist, and Wikipedia; “leaderless” nonprofit organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous and the Young Presidents Organization; and highly decentralized religious movements like the Quakers and al Qaeda.

With respect to this chapter, their insights about champions are particularly interesting. A champion is someone who is consumed with an idea and has the talent to rally others behind that idea. Brafman and Beckstrom argue that the passion and enthusiasm of champions attracts followers, and their persistence enables the group to endure all the obstacles to change. Classic champions of the past include Thomas Clarkson, a Quaker driven to end slavery, and Leor Jacobi, a vegan driven to end meat-eating. In the end, this book argues that change champions are as much if not more important to the future survival of the organization than even the formal leaders of the organization.

5.4 Practices for Cultivating Capable Champions

To conclude this chapter, I once gain offer seven practices that can enable an organization to cultivate capable champions. As Ralph Waldo Emerson was quoted at the beginning of this chapter, nothing great ever gets accomplished without enthusiasm. Champions are passionate enthusiasts leading change initiatives.

Practice 1: Hire, Develop, and Retain Change Agents

Many senior executives confine themselves to looking only one level down from the top and conclude incorrectly that there are not enough people to lead change initiatives. As a result, they often hire newcomers or consultants too quickly and put them in influential change agent positions. While this is sometimes unavoidable, this approach has a major downside to it since it signals that the senior leadership does not trust existing managers to champion change.

A much better approach is to hire potential change agents to help ensure the organization’s future. However, change agents are mavericks by nature, and the hiring decision either consciously or unconsciously screens out individuals “who don’t fit in.” This is why hiring decisions are often better made by those who have actually led others to be superior to staff persons with no actual leadership experience or background.

Practice 2: Listen to Middle Managers, Especially Those Who Deal Directly With Customers

In the previous chapter, it was emphasized that senior leaders need to dialogue with and listen to their employees. This is especially true of change agents within the middle management ranks. For example, an organizational study of governmental agencies found that senior leaders of agencies that engaged in dialogue with the middle management ranks were much more successful in pursuing change than senior leaders of agencies that used a more top-down, one-way communication style. Change agents have unique and detailed perspectives on the entire organization as well as its customers. Senior leaders need two-way communication to tap this knowledge.

Practice 3: Identify Who Your Change Champions Are

Unusually effective middle managers are tremendous repositories of change champions. A recent Harvard Business Review article offers insights on how to identify who the change champions might be.Huy (2001). First, look for early volunteers. These individuals often have the confidence and enthusiasm to tackle the risky and ambiguous nature of change. They often feel constrained in their current duties, and are eager for more responsibility. Give it to them.

Second, look for positive critics. Change-resistant managers constantly find reasons why a change proposal won’t work, and they seldom, if ever, offer a counterproposal. In contrast, positive critics challenge existing proposals, suggest alternatives, and provide evidence to support their argument. Positive critics offer constructive criticism and positive criticism is essential to being a change champion.

Third, look for people with informal power. They are often middle managers whose advice and help are highly sought after by people all around them. They often have excellent reputations and a lot of “social capital.” They typically operate at the center of large informal networks, and know how to work with that network successfully.

Fourth, look for individuals who are versatile. Change champions need to be comfortable with change, and they often adapt more easily to previous organization change more readily and easily than others in the organization. Those who have endured in their career shifts, relocations, or both are more likely to be comfortable with change than those who have not undergone these professional changes.

Finally, look for emotional intelligence in your middle management ranks. Individuals who are aware of their own emotions and those of others, and actively take steps to manage their feelings, are more likely to adapt to an envisioned change. Emotional intelligence is much more important than traditional logical-mathematical intelligence. Using the vernacular of the day, change champions need “emotional” bandwidth.Davis (1997).

Practice 4: Recognize and Reward Effective Change Champions

Organizations are designed to reduce variation; change champions are oriented to creating variation. How can these two different orientations co-exist? Clearly, there needs to be a balance here. Unfortunately, most organizations only reward managers who reduce variation and punish or, more likely, ignore those who amplify variation.

Due to the messiness and uncertainty behind change, change champions are more likely to make mistakes. Organizations need to learn to find a way to reward effectiveness in addition to efficiency. Making mistakes is not efficient, but it can be effective. Does your organization recognize and reward an efficiently run organizational unit that hasn’t changed much in years as well as an organizational unit that has changed completely, but in the process angered some individuals along the way? Change champions make mistakes, but they learn from their mistakes and they ultimately succeed. As hard as it is for organizations, they need to be recognized and rewarded for doing so.

Practice 5: Train and Develop Middle Managers to Be Change Agents

Noel Tichy argues that effective companies build leaders at every level, and they do this by creating a “leadership engine.” This is especially true for the development of change champions. In Tichy’s view, the best leaders are “enablers” rather than “doers.” They work their initiatives through other people rather than doing it all themselves. They can only accomplish this, he adds, if they develop people sufficiently to ensure that proper execution can occur at all levels.Tichy and Cohen (1997).

In large organizations, a formal leadership development program is often created to identify and accelerate the development of change champions. In medium- and small-sized organizations, an informal leadership development program is often sufficient. Regardless of the formality of the program, the key notion here is the importance of “contextualized” training and development. Traditional training and development leads to new knowledge, but has little impact on organizational change. Training and development that is applied to actual work situations through such practices as action learning projects, leadership mentoring, and applied learning endeavors go hand-in-hand with organizational change.McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison (1988).

Practice 6: Use Cross-Functional Teams to Bring About Change

Organization-wide change requires cross-function teams to guide the change initiative. Without a cross-functional team, unrepresented organizational units are more likely to resist the change since it is assumed that their voice is not heard or considered. Ideally, the cross-functional team will comprise respected change champions from the various subunits. At a minimum, the team must be led by a change champion.

Cross-functional teams are different from the more traditional functional team. They can speed new product development cycles, increase creative problem solving, serve as a forum for organizational learning, and be a single point of contact for key stakeholder groups. Because of this unique structure and mandate, team leadership is different for a cross-functional team than for a functional team. Specifically, technical skills are relatively less important for these types of teams, but conceptual and interpersonal skills are more important. Hence, the creation and composition of cross-functional teams can be an excellent way to identify and develop your change champions.Parker (2002).

Practice 7: Understand the Nature and Power of “Sponsorship”

The sponsor of a change typically comes from the CEO or top management team. Senior leaders authorize change efforts and often provide tangible resources to make that change a reality. However, they also provide intangible and symbolic resources to change champions. If the sponsor announces a change initiative, creates a guiding coalition, and then disappears from view, the organization will notice and the change initiative will suffer. If the sponsor announces a change initiative, creates a guiding coalition, makes him or herself available to support and learn about progress to the team, and regularly voice support for the change initiative, then the change initiative has a much better chance of success.

The relationship between the senior leader and the change champion is particularly important. Since the change champion lacks the authority to get things done and some changes can only be brought about by formal authority, the sponsor must use his or her authority at times to keep up the change momentum. By the same token, change champions should never undertake leadership of a change initiative without solid support and sponsorship by senior leader(s). Without effective sponsorship, change champions are highly unlikely to succeed.

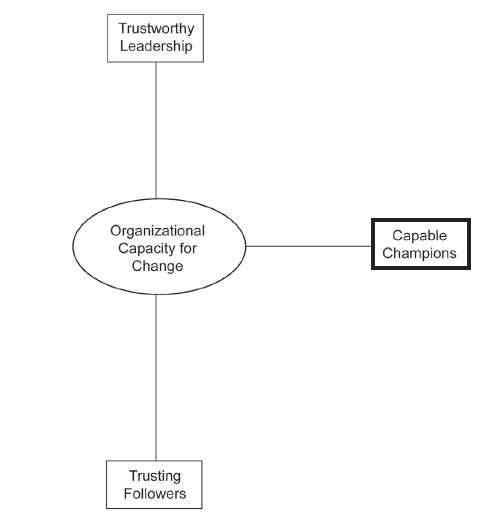

In sum, lateral relationships and influence without authority are as important to organizational change capacity as vertical relationships and authority are. This chapter discusses how creating a cadre of capable champions is essential for bringing about change. Figure 5.1 "The Third Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Capable Champions" contains a graphical depiction of this third dimension of capacity for change.

Figure 5.1 The Third Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Capable Champions