This is “International HRM”, chapter 14 from the book Beginning Management of Human Resources (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 14 International HRM

Things Weren’t What They Seemed

When your organization decided to go “global” two years ago, the executives didn’t know what they were getting into. While the international market was attractive for your company’s product, the overall plan wasn’t executed well. The organization was having great success selling its baby bath product in the domestic market, and once that market was saturated, the organization decided to sell the product in South America. Millions of dollars’ worth of research went into product marketing, and great success was had selling the product internationally. It was only when the organization decided to develop a sales presence in Peru and purchase a company there that the problems started. While market research had been done on the product itself, the executives of the company did little research to find out the cultural, economic, and legal aspects of doing business in that country. It was assumed that the Peru office would run just like the US office in terms of benefits, compensation, and hiring practices. This is where the strategy went wrong.

Many cultural aspects presented themselves. When executives visited the Peru office, the meeting was scheduled for 9 a.m., and executives were annoyed that the meeting didn’t actually start until 9:45 a.m. When the annoyed executives started in on business immediately, the Peruvian executives disapproved, but the US executives thought they disapproved of the ideas and weren’t aware that the disapproval came from the fact that Peruvians place a high emphasis on relationships, and it was rude to get down to business right away. When the executives walked around the office and spoke with various employees, this blunder cost respect from the Peruvian executives. Because Peru has a hierarchical structure, it was considered inappropriate for the executives to engage employees in this way; they should have been speaking with management instead.

Besides the cultural misunderstandings, executives had grossly underestimated the cost of compensation in Peru. Peru requires that all employees receive a bonus on the Peruvian Independence Day and another on Christmas. The bonus is similar to the monthly salary. After a year of service, Peruvians are allowed to go on paid vacation for thirty calendar days. Higher benefit costs were also an issue as well, since Peru requires workers to contribute 22 percent of their income to pension plans, and the company is required to pay 9 percent of salaries toward social (universal) health insurance. Life insurance is also required to be paid by the employer after four years of service, and severance payments are compulsory if the organization has a work stoppage or slowdown.

As you wade through the variety of rules and regulations, you think that this could have been avoided if research had been performed before the buyout happened. If this had occurred, your company would have known the actual costs to operate overseas and could have planned better.

Source: Based on information from CIA World Factbook and PKF Business Advisors.

International HRM Introduction

(click to see video)The author introduces the chapter on international HRM.

14.1 Offshoring, Outsourcing

Learning Objectives

- Be able to explain the terminology related to international HRM.

- Define global HRM strategies.

- Explain the impact of culture on HRM practices.

As you already know, this chapter is all about strategic human resource management (HRM) in a global environment. If this is an area of HRM that interests you, consider taking the WorldatWork Global Remuneration Professional certification (GRP). The GRP consists of eight examinations ranging from global rewards strategy to job analysis in a global setting.“Global Remuneration Professional,” WorldatWork Society of Certified Professionals, accessed August 10, 2010, http://www.worldatworksociety.org/society/certification/html/certification-grp.jsp.

Before we begin to discuss HRM in a global environment, it is important to define a few terms, some of which you may already know. First, offshoringWhen a business relocates or moves some or part of its operations to another country. is when a business relocates or moves some or part of its operations to another country. OutsourcingContracting with another company (onshore or offshore) to perform some business-related task. involves contracting with another company (onshore or offshore) to perform some business-related task. For example, a company may decide to outsource its accounting operations to a company that specializes in accounting, rather than have an in-house department perform this function. Thus a company can outsource the accounting department, and if the function operates in another country, this would also be offshoring. The focus of this chapter will be on the HRM function when work is offshored.

The Global Enviornment

Although the terms international, global multinational, and transnational tend to be used interchangeably, there are distinct differences. First, a domesticA market in which a product or service is sold only within the borders of that country. market is one in which a product or service is sold only within the borders of that country. An internationalA company may find that it has saturated the domestic market for the product, so it seeks out international markets in which to sell its product. market is one in which a company may find that it has saturated the domestic market for the product, so it seeks out international markets in which to sell its product. Since international markets use their existing resources to expand, they do not respond to local markets as well as a global organization. A globalA type of organization in which a product is being sold globally, and the organization looks at the world as its market. organization is one in which a product is being sold globally, and the organization looks at the world as its market. The local responsiveness is high with a global organization. A multinationalA company that produces and sells products in other markets, unlike an international market in which products are produced domestically and then sold overseas. is a company that produces and sells products in other markets, unlike an international market in which products are produced domestically and then sold overseas. A transnationalA complex organization with a corporate office, but unlike international, global, and multinational companies, much of the decision making, research and development, and marketing is left up to the individual foreign market. company is a complex organization with a corporate office, but the difference is that much of the decision making, research and development, and marketing are left up to the individual foreign market. The advantage to a transnational is the ability to respond locally to market demands and needs. The challenge in this type of organization is the ability to integrate the international offices. Coca-Cola, for example, engaged first in the domestic market, sold products in an international market, and then became multinational. The organization then realized they could obtain certain production and market efficiencies in transitioning to a transnational company, taking advantage of the local market knowledge.

Table 14.1 Differences between International, Global, Multinational, and Transnational Companies

| Global | Transnational |

| Centrally controlled operations | Foreign offices have control over production, markets |

| No need for home office integration, since home office makes all decisions | Integration with home office |

| Views the world as its market | High local responsiveness |

| Low market responsiveness, since it is centrally controlled | |

| International | Multinational |

| Centrally controlled | Foreign offices are viewed as subsidiaries |

| No need for home office integration, as home office makes all decisions | Home office still has much control |

| Uses existing production to sell products overseas | High local responsiveness |

| Low market responsiveness |

Globalization has had far-reaching effects in business but also in strategic HRM planning. The signing of trade agreements, growth of new markets such as China, education, economics, and legal implications all impact international business.

Trade agreements have made trade easier for companies. A trade agreementAn agreement between two or more countries to reduce barriers to trade. is an agreement between two or more countries to reduce barriers to trade. For example, the European Union consists of twenty-seven countries (currently, with five additional countries as applicants) with the goal of eliminating trade barriers. The North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA) lifts barriers to trade between Canada, the United States, and Mexico. The result of these trade agreements and many others is that doing business overseas is a necessity for organizations. It can result in less expensive production and more potential customers. Because of this, along with the strategic planning aspects of a global operation, human resources needs to be strategic as well. Part of this strategic process can include staffing differences, compensation differences, differences in employment law, and necessary training to prepare the workforce for a global perspective. Through the use of trade agreements and growth of new markets, such as the Chinese market, there are more places available to sell products, which means companies must be strategically positioned to sell the right product in the right market. High performance in these markets requires human capital that is able to make these types of decisions.

The level of education in the countries in which business operates is very important to the HR manager. Before a business decides to expand into a particular country, knowledge of the education, skills, and abilities of workers in that country can mean a successful venture or an unsuccessful one if the human capital needs are not met. Much of a country’s human capital depends on the importance of education to that particular country. In Denmark, for example, college educations are free and therefore result in a high percentage of well-educated people. In Somalia, with a GDP of $600 per person per year, the focus is not on education but on basic needs and survival.

Economics heavily influences HRM. Because there is economic incentive to work harder in capitalist societies, individuals may be more motivated than in communist societies. The motivation comes from workers knowing that if they work hard for something, it cannot be taken away by the government, through direct seizure or through higher taxes. Since costs of labor are one of the most important strategic considerations, understanding of compensation systems (often based on economics of the country) is an important topic. This is discussed in more detail in Section 14.3.3 "Compensation and Rewards".

The legal system practiced in a country has a great effect on the types of compensation; union issues; how people are hired, fired, and laid off; and safety issues. Rules on discrimination, for example, are set by the country. In China, for example, it is acceptable to ask someone their age, marital status, and other questions that would be considered illegal in the United States. In another legal example, in Costa Rica, “aguinaldos” also known as a thirteenth month salary, is required in December.“Labor Laws and Policy,” The Real Costa Rica, accessed April 29, 2011, http://www.therealcostarica.com/costa_rica_business/costa_rica_labor_law.html. This is a legal requirement for all companies operating in Costa Rica. We discuss more specifics about international laws in Section 14.3.5 "The International Labor Environment".

Table 14.2 Top Global 100 Companies

| Rank | Company | Revenues ($ millions) | Profits ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Walmart Stores | 408,214 | 14,335 |

| 2 | Royal Dutch Shell | 285,129 | 12,518 |

| 3 | Exxon Mobil | 284,650 | 19,280 |

| 4 | BP | 246,138 | 16,578 |

| 5 | Toyota Motor | 204,106 | 2,256 |

| 6 | Japan Post Holdings | 202,196 | 4,849 |

| 7 | Sinopec | 187,518 | 5,756 |

| 8 | State Grid | 184,496 | −343 |

| 9 | AXA | 175,257 | 5,012 |

| 10 | China National Petroleum | 165,496 | 10,272 |

| 11 | Chevron | 163,527 | 10,483 |

| 12 | ING Group | 163,204 | −1,300 |

| 13 | General Electric | 156,779 | 11,025 |

| 14 | Total | 155,887 | 11,741 |

| 15 | Bank of America Corp. | 150,450 | 6,276 |

| 16 | Volkswagen | 146,205 | 1,334 |

| 17 | ConocoPhillips | 139,515 | 4,858 |

| 18 | BNP Paribas | 130,708 | 8,106 |

| 19 | Assicurazioni Generali | 126,012 | 1,820 |

| 20 | Allianz | 125,999 | 5,973 |

| 21 | AT&T | 123,018 | 12,535 |

| 22 | Carrefour | 121,452 | 454 |

| 23 | Ford Motor | 118,308 | 2,717 |

| 24 | ENI | 117,235 | 6,070 |

| 25 | J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. | 115,632 | 11,728 |

| 26 | Hewlett-Packard | 114,552 | 7,660 |

| 27 | E.ON | 113,849 | 11,670 |

| 28 | Berkshire Hathaway | 112,493 | 8,055 |

| 29 | GDF Suez | 111,069 | 6,223 |

| 30 | Daimler | 109,700 | −3,670 |

| 31 | Nippon Telegraph & Telephone | 109,656 | 5,302 |

| 32 | Samsung Electronics | 108,927 | 7,562 |

| 33 | Citigroup | 108,785 | −1,606 |

| 34 | McKesson | 108,702 | 1,263 |

| 35 | Verizon Communications | 107,808 | 3,651 |

| 36 | Crédit Agricole | 106,538 | 1,564 |

| 37 | Banco Santander | 106,345 | 12,430 |

| 38 | General Motors | 104,589 | — |

| 39 | HSBC Holdings | 103,736 | 5,834 |

| 40 | Siemens | 103,605 | 3,097 |

| 41 | American International Group | 103,189 | −10,949 |

| 42 | Lloyds Banking Group | 102,967 | 4,409 |

| 43 | Cardinal Health | 99,613 | 1,152 |

| 44 | Nestlé | 99,114 | 9,604 |

| 45 | CVS Caremark | 98,729 | 3,696 |

| 46 | Wells Fargo | 98,636 | 12,275 |

| 47 | Hitachi | 96,593 | −1,152 |

| 48 | International Business Machines | 95,758 | 13,425 |

| 49 | Dexia Group | 95,144 | 1,404 |

| 50 | Gazprom | 94,472 | 24,556 |

| 51 | Honda Motor | 92,400 | 2,891 |

| 52 | Électricité de France | 92,204 | 5,428 |

| 53 | Aviva | 92,140 | 1,692 |

| 54 | Petrobras | 91,869 | 15,504 |

| 55 | Royal Bank of Scotland | 91,767 | −4,167 |

| 56 | PDVSA | 91,182 | 1,608 |

| 57 | Metro | 91,152 | 532 |

| 58 | Tesco | 90,234 | 3,690 |

| 59 | Deutsche Telekom | 89,794 | 491 |

| 60 | Enel | 89,329 | 7,499 |

| 61 | UnitedHealth Group | 87,138 | 3,822 |

| 62 | Société Générale | 84,157 | 942 |

| 63 | Nissan Motor | 80,963 | 456 |

| 64 | Pemex | 80,722 | −7,011 |

| 65 | Panasonic | 79,893 | −1,114 |

| 66 | Procter & Gamble | 79,697 | 13,436 |

| 67 | LG | 78,892 | 1,206 |

| 68 | Telefónica | 78,853 | 10,808 |

| 69 | Sony | 77,696 | −439 |

| 70 | Kroger | 76,733 | 70 |

| 71 | Groupe BPCE | 76,464 | 746 |

| 72 | Prudential | 75,010 | 1,054 |

| 73 | Munich Re Group | 74,764 | 3,504 |

| 74 | Statoil | 74,000 | 2,912 |

| 75 | Nippon Life Insurance | 72,051 | 2,624 |

| 76 | AmerisourceBergen | 71,789 | 503 |

| 77 | China Mobile Communications | 71,749 | 11,656 |

| 78 | Hyundai Motor | 71,678 | 2,330 |

| 79 | Costco Wholesale | 71,422 | 1,086 |

| 80 | Vodafone | 70,899 | 13,782 |

| 81 | BASF | 70,461 | 1,960 |

| 82 | BMW | 70,444 | 284 |

| 83 | Zurich Financial Services | 70,272 | 3,215 |

| 84 | Valero Energy | 70,035 | −1,982 |

| 85 | Fiat | 69,639 | −1,165 |

| 86 | Deutsche Post | 69,427 | 895 |

| 87 | Industrial & Commercial Bank of China | 69,295 | 18,832 |

| 88 | Archer Daniels Midland | 69,207 | 1,707 |

| 89 | Toshiba | 68,731 | −213 |

| 90 | Legal & General Group | 68,290 | 1,346 |

| 91 | Boeing | 68,281 | 1,312 |

| 92 | US Postal Service | 68,090 | −3,794 |

| 93 | Lukoil | 68,025 | 7,011 |

| 94 | Peugeot | 67,297 | −1,614 |

| 95 | CNP Assurances | 66,556 | 1,396 |

| 96 | Barclays | 66,533 | 14,648 |

| 97 | Home Depot | 66,176 | 2,661 |

| 98 | Target | 65,357 | 2,488 |

| 99 | ArcelorMittal | 65,110 | 118 |

| 100 | WellPoint | 65,028 | 4,746 |

| Source: Adapted from Fortune 500 List 2010, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/global500/2010/full_list/ (accessed August 11, 2011). | |||

Global HR Trends

(click to see video)Howard Wallack, director of Global Member programs for the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), talks about some of the global HR trends and gives tips on how to deal with these trends from the HR perspective.

HRM Global Strategies

When discussing HRM from the global perspective, there are many considerations. Culture, language, management styles, and laws would all be considerations before implementing HRM strategies. Beechler et al.Schon Beechler, Vladimir Pucik, John Stephan, and Nigel Campbell, “The Transnational Challenge: Performance and Expatriate Presence in the Overseas Affiliates of Japanese MNCs,” in Japanese Firms in Transition: Responding to the Globalization Challenge, Advances in International Management, vol. 17, ed. Tom Roehl and Allan Bird (Bingley, UK: Emerald Group, 2004), 215–42. argued that for multinational companies, identifying the best HRM processes for the entire organization isn’t the goal, but rather finding the best fit between the firm’s external environment (i.e., the law) and the company’s overall strategy, HRM policies, and implementation of those policies. To this end, Adler and Bartholomew developed a set of transnational competencies that are required for business to thrive in a global business environment.Nancy J. Adler and Susan Bartholomew, “Managing Globally Competent People,” Executive 6, no. 3 (1992): 52–65. A transnational scopeWhen HRM decisions can be made based on the international scope rather than the domestic one. means that HRM decisions can be made based on an international scope; that is, HRM strategic decisions can be made from the global perspective rather than a domestic one. With this HRM strategy, decisions take into consideration the needs of all employees in all countries in which the company operates. The concern is the ability to establish standards that are fair for all employees, regardless of which country they operate in. A transnational representationWhen the composition of the firm’s managers and executives is a multinational one. means that the composition of the firm’s managers and executives should be a multinational one. A transnational processRefers to the extent to which ideas that contribute to the organization come from a variety of perspectives and ideas from all countries in which the organization operates., then, refers to the extent to which ideas that contribute to the organization come from a variety of perspectives and ideas from all countries in which the organization operates. Ideally, all company processes will be based on the transnational approach. This approach means that multicultural understanding is taken into consideration, and rather than trying to get international employees to fit within the scope of the domestic market, a more holistic approach to HRM is used. Using a transnational approach means that HRM policies and practices are a crucial part of a successful business, because they can act as mechanisms for coordination and control for the international operations.Markus Pudelko and Anne-Wil Harzing, “Country-of-Origin, Localization, or Dominance Effect? An Empirical Investigation of HRM Practices in Foreign Subsidiaries,” Human Resource Management 46, no. 4 (2007): 535–59. In other words, HRM can be the glue that sticks many independent operations together.

Before we look at HRM strategy on the global level, let’s discuss some of the considerations before implementing HRM systems.

Culture as a Major Aspect of HRM Overseas

Culture is a key component to managing HRM on a global scale. Understanding culture but also appreciating cultural differences can help the HRM strategy be successful in any country. Geert Hofstede, a researcher in the area of culture, developed a list of five cultural dimensions that can help define how cultures are different.Geert Hofstede, Cultural Dimensions website, accessed April 29, 2011, http://www.geert-hofstede.com/.

The first dimension of culture is individualism-collectivismOne of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions; describes the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups.. In this dimension, Hofstede describes the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. For example, in the United States, we are an individualist society; that is, each person looks after him- or herself and immediate family. There is more focus on individual accomplishments as opposed to group accomplishments. In a collective society, societies are based on cohesive groups, whether it be family groups or work groups. As a result, the focus is on the good of the group, rather than the individual.

Figure 14.1

One of the factors of culture is nonverbal language, such as the use of handshakes, kissing, or bowing.

© Thinkstock

Power distanceOne of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions; refers to the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations accept that power is not distributed equally., Hofstede’s second dimension, refers to the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations accept that power is not distributed equally. For example, some societies may seek to eliminate differences in power and wealth, while others prefer a higher power distance. From an HRM perspective, these differences may become clear when employees are asked to work in cross-functional teams. A Danish manager may have no problem taking advice from employees because of the low power distance of his culture, but a Saudi Arabian manager may have issues with an informal relationship with employees, because of the high power distance.

Uncertainty avoidanceOne of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions; refers to how a society tolerates uncertainty. refers to how a society tolerates uncertainty. Countries that focus more on avoidance tend to minimize the uncertainty and therefore have stricter laws, rules, and other safety measures. Countries that are more tolerant of uncertainty tend to be more easygoing and relaxed. Consider the situation in which a company in the United States decides to apply the same HRM strategy to its operations in Peru. The United States has an uncertainty avoidance score of 46, which means the society is more comfortable with uncertainty. Peru has a high uncertainty avoidance, with a score of 87, indicating the society’s low level of tolerance for uncertainty. Let’s suppose a major part of the pay structure is bonuses. Would it make sense to implement this same compensation plan in international operations? Probably not.

Masculinity and femininityOne of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions; refers to the distribution of emotional roles between genders, and which gender norms are accepted by society. refers to the distribution of emotional roles between genders, and which gender norms are accepted by society. For example, in countries that are focused on femininity, traditional “female” values such as caring are more important than, say, showing off. The implications to HRM are huge. For example, Sweden has a more feminine culture, which is demonstrated in its management practices. A major component in managers’ performance appraisals is to provide mentoring to employees. A manager coming from a more masculine culture may not be able to perform this aspect of the job as well, or he or she may take more practice to be able to do it.

The last dimension is long-term–short-term orientationOne of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions; refers to the society’s time horizons., which refers to the society’s time horizons. A long-term orientation would focus on future rewards for work now, persistence, and ordering of relationships by status. A short-term orientation may focus on values related to the past and present such as national pride or fulfillment of current obligations. We can see HRM dimensions with this orientation in succession planning, for example. In China the person getting promoted might be the person who has been with the company the longest, whereas in short-term orientation countries like the United States, promotion is usually based on merit. An American working for a Chinese company may get upset to see someone promoted who doesn’t do as good of a job, just because they have been there longer, and vice versa.

Based on Hofstede’s dimensions, you can see the importance of culture to development of an international HRM strategy. To utilize a transnational strategy, all these components should be factored into all decisions such as hiring, compensation, and training. Since culture is a key component in HRM, it is important now to define some other elements of culture.

Table 14.3 Examples of Countries and Hofstede’s Dimensions

| Country | Power Distance | Individualism/Collectivism | Masculinity/Femininity | Uncertainty Avoidance | Long/Short Term Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | 22 | 79 | 58 | 49 | 30 |

| UK | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 25 |

| United States | 40 | 91 | 62 | 46 | 29 |

| Japan | 54 | 46 | 95 | 92 | 80 |

| Taiwan | 58 | 17 | 45 | 69 | 87 |

| Zambia | 64 | 27 | 41 | 52 | 25 |

| India | 77 | 48 | 56 | 40 | 61 |

| China | 80 | 20 | 66 | 40 | 118 |

| Philippines | 94 | 32 | 64 | 44 | 19 |

| Chile | 63 | 23 | 28 | 86 | (this dimension was only studied in 23 countries) |

| Power distance: Refers to the comfort level of power differences among society members. A lower score shows greater equality among levels of society, such as New Zealand. | |||||

| Individualism/collectivism: A high ranking here, such as the United States, means there is more concern for the individualistic aspects of society as opposed to collectivism. Countries with high scores on individualism means the people tend to be more self-reliant. | |||||

| Masculinity/femininity: A lower score may indicate lower levels of differentiation between genders. A lower score, such as Chile, may also indicate a more openly nurturing society. | |||||

| Uncertainty avoidance: Refers to the tolerance for uncertainty. A high score, such as Japan’s, means there is lower tolerance for uncertainty, so rules, laws, policies, and regulations are implemented. | |||||

| Long/short term orientation: Refers to thrift and perseverance, overcoming obstacles with time (long-term orientation), such as China, versus tradition, social obligations. | |||||

CultureRefers to the socially accepted ways of life within a society. refers to the socially accepted ways of life within a society. Some of these components might include language, normsShared expectations about what is considered correct and normal behavior., valuesIn a culture, the classification of things as good or bad within a society., ritualsScripted ways of interacting that usually result in a specific series of events., and material cultureThe items a culture holds important, such as artwork, technology, and architecture. such as art, music, and tools used in that culture. Language is perhaps one of the most obvious parts of culture. Often language can define a culture and of course is necessary to be able to do business. HRM considerations for language might include something as simple as what language (the home country or host country) will documents be sent in? Is there a standard language the company should use within its communications?

Fortune 500 Focus

For anyone who has traveled, seeing a McDonald’s overseas is common, owing to the need to expand markets. McDonald’s is perhaps one of the best examples of using cultural sensitivity in setting up its operations despite criticism for aggressive globalization. Since food is usually a large part of culture, McDonald’s knew that when globalizing, it had to take culture into consideration to be successful. For example, when McDonald’s decided to enter the Indian market in 2009, it knew it needed a vegetarian product. After several hundred versions, local McDonald’s executives finally decided on the McSpicy Paneer as the main menu item. The spicy Paneer is made from curd cheese and reflects the values and norms of the culture.Gus Lubin, “A Brilliant Lesson in Globalization from McDonalds,” Business Insider, June 16, 2011, accessed August 13, 2011, http://www.businessinsider.com/a-brilliant-lesson-in-globalization-from-mcdonalds-2011-6.

In Japan, McDonald’s developed the Teriyaki Burger and started selling green tea ice cream. When McDonald’s first started competing in Japan, there really was no competition at all, but not for the reason you might think. Japanese people looked at McDonald’s as a snack rather than a meal because of their cultural values. Japanese people believe that meals should be shared, which can be difficult with McDonald’s food. Second, the meal did not consist of rice, and a real Japanese meal includes rice—a part of the national identityEmiko Ohnuki-Tierney, “McDonald’s in Japan: Changing Manners and Etiquette,” in Golden Arches East: McDonald’s in East Asia, ed. J. L. Watson (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997), 161-82. and values. Most recently, McDonald’s introduced the McBaguette in France to align with French cultural values.Sarah Rappanport, “McDonalds Introduces France to the McBaguette,” Business Insider Europe, July 29, 2011, accessed August 12, 2011, http://www.businessinsider.com/mcbaguette-mcdonalds-france-2011-7. The McBaguettes will be produced in France and come with a variety of jams, a traditional French breakfast. Just like in product development, HRM must understand the differences between cultures to create the best HRM systems that work for the individual culture.

Norms are shared expectations about what is considered correct and normal behavior. Norms allow a society to predict the expected behavior and be able to act in this manner. For many companies operating in the United States, a norm might be to dress down for work, no suit required. But if doing business overseas, that country’s norm might be to wear a suit. Not understanding the norms of a culture can offend potential clients, customers, and colleagues.

Values, another part of culture, classify things as good or bad within a society. Values can evoke strong emotional feelings from a person or a society. For example, burning of the American flag results in strong emotions because values (love of country and the symbols that represent it) are a key component of how people view themselves, and how a culture views society. In April 2011, a pastor in Florida burned a holy book, the Koran, which sparked outrage from the Muslim community all over the world. This is an example of a strongly held value that when challenged can result in community rage.Sarah Drury, “Violent Protests Over Koran Burning Spread,” ABC News, April 4, 2011, accessed April 27, 2011, http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/content/2011/s3181541.htm.

Rituals are scripted ways of interacting that usually result in a specific series of events. Consider a wedding in the United States, for example. The basic wedding rituals (first dance, cutting of cake, speech from best man and bridesmaid) are practiced throughout society. Besides the more formalized rituals within a society, such as weddings or funerals, daily rituals, such as asking someone “How are you?” (when you really don’t want to know the answer) are part of culture, too. Even bonding rituals such as how business cards are exchanged and the amount of eye contact given in a social situation can all be rituals as well.

The material items a culture holds important, such as artwork, technology, and architecture, can be considered material culture. Material culture can range from symbolic items, such as a crucifix, or everyday items, such as a Crockpot or juicer. Understanding the material importance of certain items to a country can result in a better understanding of culture overall.

Cultural Differences

(click to see video)This funny commercial notes examples of cultural differences.

Human Resource Recall

Which component of culture do you think is the most important in HRM? Why?

Key Takeaways

- Offshoring is when a business relocates or moves part of its operations to a country different from the one it currently operates in.

- Outsourcing is when a company contracts with another company to do some work for another. This can occur domestically or in an offshoring situation.

- Domestic market means that a product is sold only within the country that the business operates in.

- An international market means that an organization is selling products in other countries, while a multinational one means that not only are products being sold in a country, but operations are set up and run in a country other than where the business began.

- The goal of any HRM strategy is to be transnational, which consists of three components. First, the transnational scope involves the ability to make decisions on a global level rather than a domestic one. Transnational representation means that managers from all countries in which the business operates are involved in business decisions. Finally, a transnational process means that the organization can involve a variety of perspectives, rather than only a domestic one.

- Part of understanding HRM internationally is to understand culture. Hofstede developed five dimensions of culture. First, there is the individualism-collectivism aspect, which refers to the tendency of a country to focus on individuals versus the good of the group.

- The second Hofstede dimension is power distance, that is, how willing people are to accept unequal distributions of power.

- The third is uncertainty avoidance, which means how willing the culture is to accept not knowing future outcomes.

- A masculine-feminine dimension refers to the acceptance of traditional male and female characteristics.

- Finally, Hofstede focused on a country’s long-term orientation versus short-term orientation in decision making.

- Other aspects of culture include norms, values, rituals, and material culture. Norms are the generally accepted way of doing things, and values are those things the culture finds important. Every country has its own set of rituals for ceremonies but also for everyday interactions. Material culture refers to the material goods, such as art, the culture finds important.

- Other HRM aspects to consider when entering a foreign market are the economics, the law, and the level of education and skill level of the human capital in that country.

Exercise

- Visit http://www.geert-hofstede.com/ and view the cultural dimensions of three countries. Then write a paragraph comparing and contrasting all three.

14.2 Staffing Internationally

Learning Objectives

- Be able to explain the three staffing strategies for international businesses and the advantages and disadvantages for each.

- Explain the reasons for expatriate failures.

One of the major decisions for HRM when a company decides to operate overseas is how the overseas operation will be staffed. This is the focus of this section.

Types of Staffing Strategy

There are three main staffing strategies a company can implement when entering an overseas market, with each having its advantages and disadvantages. The first strategy is a home-country national strategyThis staffing strategy uses employees from the home country to live and work in the country.. This staffing strategy uses employees from the home country to live and work in the country. These individuals are called expatriatesAn employee from the home country who is on international assignment in another country.. The second staffing strategy is a host-country national strategyTo employ people who were born in the country in which the business is operating., which means to employ people who were born in the country in which the business is operating. Finally, a third-country national strategy means to employee people from an entirely different country from the home country and host country. Table 14.4 "Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Staffing Strategies" lists advantages and disadvantages of each type of staffing strategy. Whichever strategy is chosen, communication with the home office and strategic alignment with overseas operations need to occur for a successful venture.

Table 14.4 Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Staffing Strategies

| Home-Country National | Host-Country National | Third-Country National | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Greater control of organization | Language barrier is eliminated | The third-country national may be better equipped to bring the international perspective to the business |

| Managers gain experience in local markets | Possible better understanding of local rules and laws | Costs associated with hiring such as visas may be less expensive than with home-country nationals | |

| Possible greater understanding and implementation of business strategy | Hiring costs such as visas are eliminated | ||

| Cultural understanding | |||

| Morale builder for employees of host country | |||

| Disadvantages | Adapting to foreign environment may be difficult for manager and family, and result in less productivity | Host-country manager may not understand business objectives as well without proper training | Must consider traditional national hostilities |

| Expatriate may not have cultural sensitivity | May create a perception of “us” versus “them” | The host government and/or local business may resent hiring a third-country national | |

| Language barriers | Can affect motivation of local workers | ||

| Cost of visa and hiring factors |

Human Resource Recall

Compare and contrast a home-country versus a host-country staffing strategy.

Expatriates

According to Simcha Ronen, a researcher on international assignments, there are five categories that determine expatriate success. They include job factors, relational dimensions, motivational state, family situation, and language skills. The likelihood the assignment will be a success depends on the attributes listed in Table 14.5 "Categories of Expatriate Success Predictors with Examples". As a result, the appropriate selection process and training can prevent some of these failings. Family stress, cultural inflexibility, emotional immaturity, too much responsibility, and longer work hours (which draw the expatriate away from family, who could also be experiencing culture shock) are some of the reasons cited for expatriate failure.

Table 14.5 Categories of Expatriate Success Predictors with Examples

| Job Factors | Relational Dimensions | Motivational State | Family Situation | Language Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical skills | Tolerance for ambiguity | Belief in the mission | Willingness of spouse to live abroad | Host-country language |

| Familiarity with host country and headquarters operations | Behavioral flexibility | Congruence with career path | Adaptive and supportive spouse | Nonverbal communication |

| Managerial skills | Nonjudgmentalism | Interest in overseas experience | Stable marriage | |

| Administrative competence | Cultural empathy and low ethnocentrism | Interest in specific host-country culture | ||

| Interpersonal skills | Willingness to acquire new patterns of behavior and attitudes |

Source: Adapted from Simcha Ronen, Training the International Assignee (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1989), 426–40.

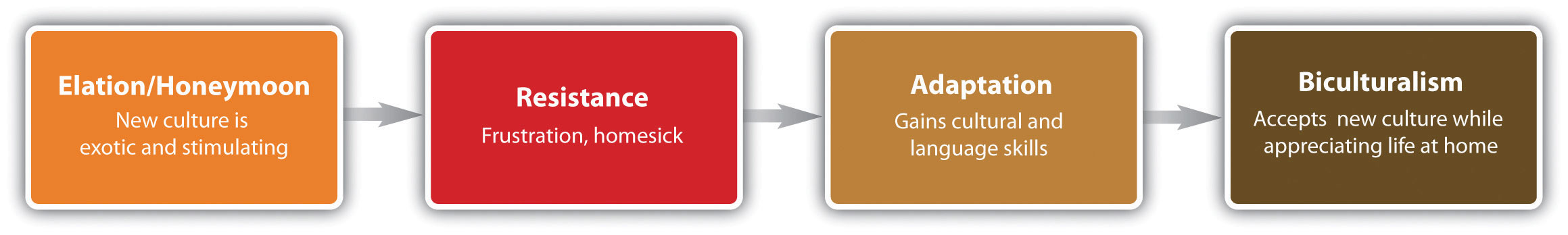

Most expatriates go through four phases of adjustment when they move overseas for an assignment. They include elation/honeymoonA phase of expatriate adjustment; the employee is excited about the new surroundings and finds the culture exotic and stimulating., resistanceA phase of expatriate adjustment; the employee may start to make frequent comparisons between home and host country and may seek out reminders of home. Frustration may occur because of everyday living, such as language and cultural differences., adaptionA phase of expatriate adjustment; the employee gains language skills and starts to adjust to life overseas. Sometimes during this phase expatriates may even tend to reject their own culture. In this phase, the expatriate is embracing life overseas., and biculturalismA phase of expatriate adjustment; the expatriate embraces the new culture and begins to appreciate his old life at home as much as his new life overseas. Many of the problems associated with expatriate failures, such as family life and cultural stress, have diminished.. In the elation phase, the employee is excited about the new surroundings and finds the culture exotic and stimulating. In the resistance phase, the employee may start to make frequent comparisons between home and host country and may seek out reminders of home. Frustration may occur because of everyday living, such as language and cultural differences. During the adaptation phase, the employee gains language skills and starts to adjust to life overseas. Sometimes during this phase, expatriates may even tend to reject their own culture. In this phase, the expatriate is embracing life overseas. In the last phase, biculturalism, the expatriate embraces the new culture and begins to appreciate his old life at home equally as much as his new life overseas. Many of the problems associated with expatriate failures, such as family life and cultural stress, have diminished.

Figure 14.2 Phases of Expatriate Adjustment

Host-Country National

The advantage, as shown in Table 14.4 "Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Staffing Strategies", of hiring a host-country national can be an important consideration when designing the staffing strategy. First, it is less costly in both moving expenses and training to hire a local person. Some of the less obvious expenses, however, may be the fact that a host-country national may be more productive from the start, as he or she does not have many of the cultural challenges associated with an overseas assignment. The host-country national already knows the culture and laws, for example. In Russia, 42 percent of respondents in an expatriate survey said that companies operating there are starting to replace expatriates with local specialists. In fact, many of the respondents want the Russian government to limit the number of expatriates working for a company to 10 percent.“Russia Starts to Abolish Expat jobs,” Expat Daily, April 27, 2011, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.expat-daily.com/news/russia-starts-to-abolish-expat-jobs/. When globalization first occurred, it was more likely that expatriates would be sent to host countries, but in 2011, many global companies are comfortable that the skills, knowledge, and abilities of managers exist in the countries in which they operate, making the hiring of a host-country national a favorable choice. Also important are the connections the host-country nationals may have. For example, Shiv Argawal, CEO of ABC Consultants in India, says, “An Indian CEO helps influence policy and regulations in the host country, and this is the factor that would make a global company consider hiring local talent as opposed to foreign talent.”Divya Rajagorpal and MC Govardhanna Rangan, “Global Firms Prefer Local Executives to Expats to Run Indian Operation,” Economic Times, April 20, 2011, accessed September 15, 2011, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2011-04-20/news/29450955_1_global-firms-joint-ventures-investment-banking.

Third-Country Nationals

One of the best examples of third-country nationals is the US military. The US military has more than seventy thousand third-country nationals working for the military in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan. For example, a recruitment firm hired by the US military called Meridian Services Agency recruits hairstylists, construction workers, and electricians from all over the world to fill positions on military bases.Sarah Stillman, “The Invisible Army,” New Yorker, June 6, 2011, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/06/06/110606fa_fact_stillman. Most companies who utilize third-country national labor are not new to multinational businesses. The majority of companies who use third-country national staffing have many operations already overseas. One example is a multinational company based in the United States that also has operations in Spain and transfers a Spanish manager to set up new operations in Argentina. This would be opposed to the company in the United States sending an American (expatriate) manager to Argentina. In this case, the third-country national approach might be the better approach because of the language aspect (both Spain and Argentina speak Spanish), which can create fewer costs in the long run. In fact, many American companies are seeing the value in hiring third-country nationals for overseas assignments. In an International Assignments Survey,“More Third Country Nationals Being Used,” n.d., SHRM India, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.shrmindia.org/more-third-country-nationals-being-used. 61 percent of United States–based companies surveyed increased the use of third-country nationals by 61 percent, and of that number, 35 percent have increased the use of third-country nationals to 50 percent of their workforce. The main reason why companies use third-country nationals as a staffing strategy is the ability of a candidate to represent the company’s interests and transfer corporate technology and competencies. Sometimes the best person to do this isn’t based in the United States or in the host country.

Key Takeaways

- There are three types of staffing strategies for an international business. First, in the home-country national strategy, people are employed from the home country to live and work in the country. These individuals are called expatriates. One advantage of this type of strategy is easier application of business objectives, although an expatriate may not be culturally versed or well accepted by the host-country employees.

- In a host-country strategy, workers are employed within that country to manage the operations of the business. Visas and language barriers are advantages of this type of hiring strategy.

- A third-country national staffing strategy means someone from a country, different from home or host country, will be employed to work overseas. There can be visa advantages to using this staffing strategy, although a disadvantage might be morale lost by host-country employees.

Exercises

- Choose a country you would enjoy working in, and visit that country’s embassy page. Discuss the requirements to obtain a work visa in that country.

- How would you personally prepare an expatriate for an international assignment? Perform additional research if necessary and outline a plan.

14.3 International HRM Considerations

Learning Objectives

- Be able to explain how the selection process for an expatriate differs from a domestic process.

- Explain possible expatriate training topics and the importance of each.

- Identify the performance review and legal differences for international assignments.

- Explain the logistical considerations for expatriate assignments.

In an international environment, as long as proper research is performed, most HRM concepts can be applied. The important thing to consider is proper research and understanding of cultural, economic, and legal differences between countries. This section will provide an overview of some specific considerations for an international business, keeping in mind that with awareness, any HRM concept can be applied to the international environment. In addition, it is important to mention again that host-country offices should be in constant communication with home-country offices to ensure policies and practices are aligned with the organization.

Recruitment and Selection

As we discussed in Section 14.2 "Staffing Internationally", understanding which staffing strategy to use is the first aspect of hiring the right person for the overseas assignment. The ideal candidate for an overseas assignment normally has the following characteristics:

- Managerial competence: technical skills, leadership skills, knowledge specific to the company operations.

- Training: The candidate either has or is willing to be trained on the language and culture of the host country.

- Adaptability: The ability to deal with new, uncomfortable, or unfamiliar situations and the ability to adjust to the culture in which the candidate will be assigned.

As we discussed earlier, when selecting an expatriate or a third-country national for the job, assuring that the candidate has the job factors, relational dimensions, motivational state, family situation, and language skills (or can learn) is a key consideration in hiring the right person. Some of the costs associated with failure of an expatriate or third-country national might include the following:

- Damage to host-country relationships

- Motivation of host-country staff

- Costs associated with recruitment and relocation

- Possible loss of that employee once he or she returns

- Missed opportunities to further develop the market

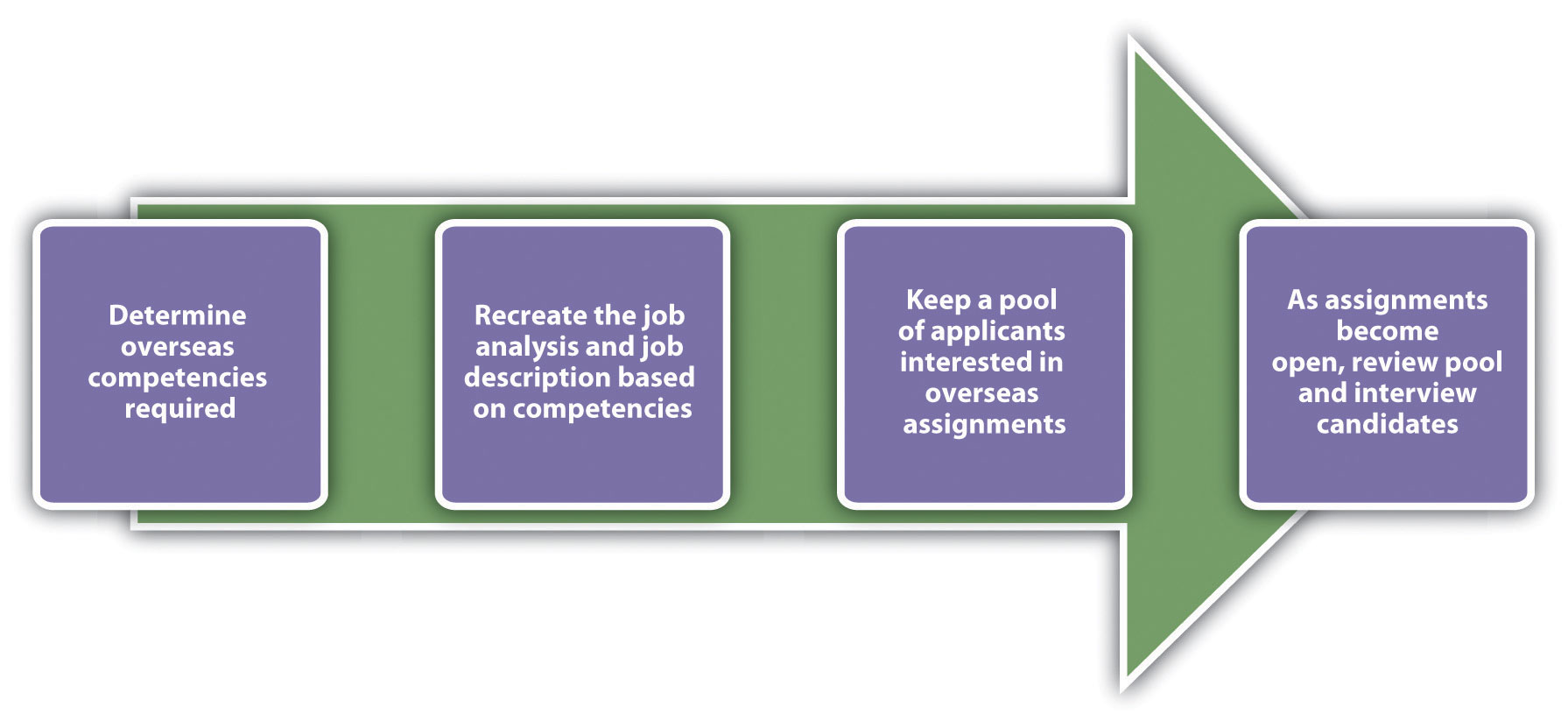

Because success on an overseas assignment has such complex factors, the selection process for this individual should be different from the selection process when hiring domestically. The process should start with the job analysis, as we discussed in Chapter 4 "Recruitment". The job analysis and job description should be different for the overseas assignment, since we know that certain competencies (besides technical ones) are important for success. Most of those competencies have little to do with the person’s ability to do the job but are related to his or her ability to do the job in a new cultural setting. These additional competencies (besides the skills needed for the job) may be considered:

- Experience working internationally

- Extroverted

- Stress tolerance

- Language skills

- Cultural experiences

Once the key success factors are determined, many of which can be based on previous overseas assignments successes, we can begin to develop a pool of internal candidates who possess the additional competencies needed for a successful overseas assignment.

To develop the pool, career development questions on the performance review can be asked to determine the employee’s interest in an overseas assignment. Interest is an important factor; otherwise, the chance of success is low. If there is interest, this person can be recorded as a possible applicant. An easy way to keep track of interested people is to keep a spreadsheet of interested parties, skills, languages spoken, cultural experiences, abilities, and how the candidates meet the competencies you have already developed.

Once an overseas assignment is open, you can view the pool of interested parties and choose the ones to interview who meet the competencies required for the particular assignment.

Figure 14.3 Sample Selection Process for Overseas Assignments

Training

Much of the training may include cultural components, which were cited by 73 percent of successful expatriates as key ingredients to success.The Economist Intelligence Unit, Up or Out: Next Moves for the Modern Expatriate, 2010, accessed April 28, 2011, http://graphics.eiu.com/upload/eb/LON_PL_Regus_WEB2.pdf.

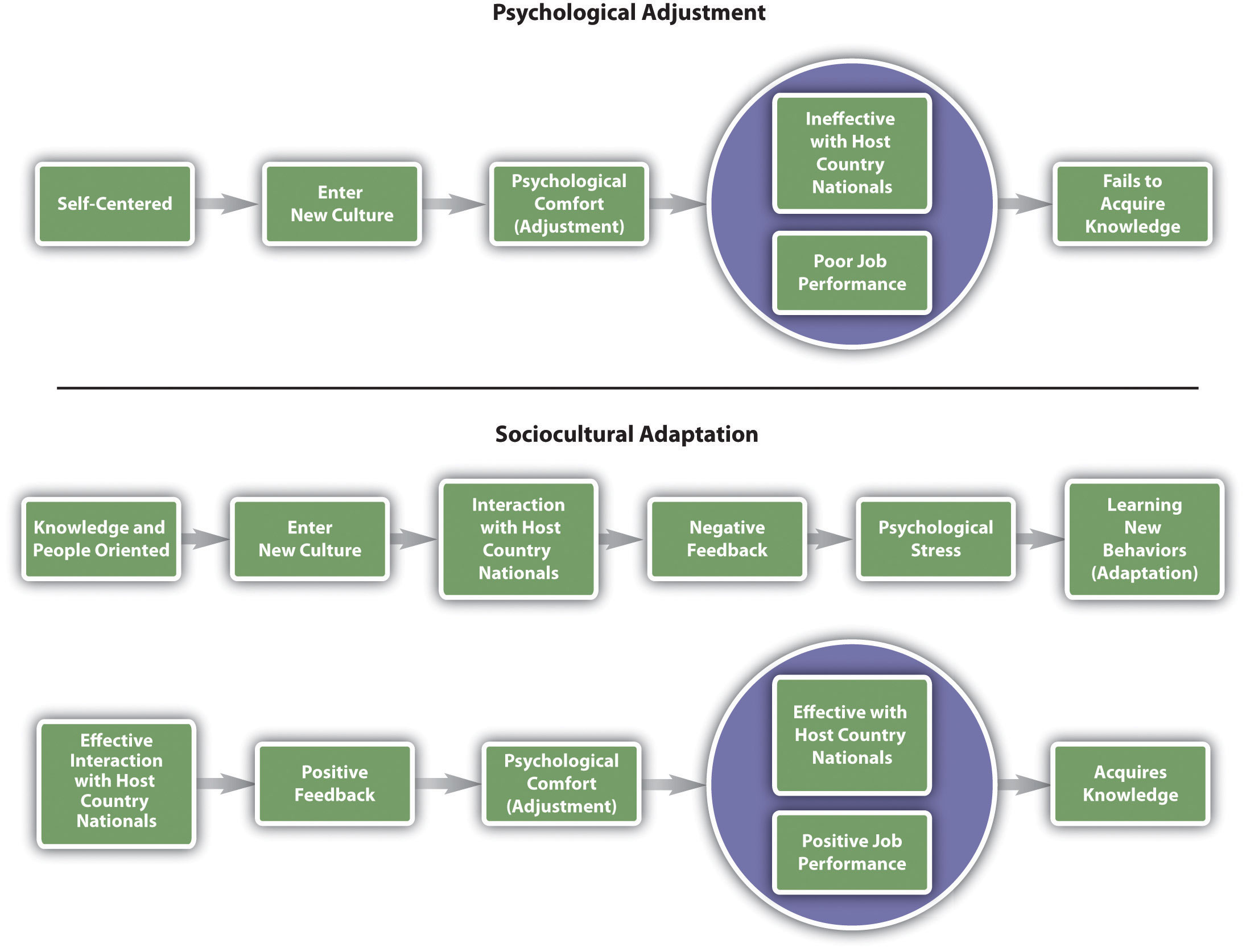

Training isn’t always easy, though. The goal is not to help someone learn a language or cultural traditions but to ensure they are immersed in the sociocultural aspects of the new culture they are living in. Roger N. Blakeney,Roger Blakeney, “Psychological Adjustment and Sociocultural Adaptation: Coping on International Assignments” (paper, Annual Meeting of Academy of Management, Atlanta, GA, 2006). an international business researcher, identifies two main pathways to adapting to a new culture. First, people adjust quickly from the psychological perspective but not the social one. Blakeney argues that adjusting solely from the psychological perspective does not make an effective expatriate. Although it may take more time to adjust, he says that to be fully immersed and to fully understand and be productive in a culture, the expatriate must also have sociocultural adaption. In other words, someone who can adjust from a sociocultural perspective ends up performing better because he or she has a deeper level of understanding of the culture. Determining whether your candidate can gain this deeper level would figure in your selection process.

Figure 14.4 Blakeney’s Model of Psychological versus Sociocultural Adaption

Source: Roger Blakeney, “Psychological Adjustment and Sociocultural Adaptation: Coping on International Assignments” (paper, Annual Meeting of Academy of Management, Atlanta, GA, 2006).

One of the key decisions in any global organization is whether training should be performed in-house or an outside company should be hired to provide the training. For example, Communicaid offers online and on-site training on a variety of topics listed. Whether in-house or external training is performed, there are five main components of training someone for an overseas assignment:

- Language

- Culture

- Goal setting

- Managing family and stress

- Repatriation

Training on languages is a basic yet necessary factor to the success of the assignment. Although to many, English is the international business language, we shouldn’t discount the ability to speak the language of the country in which one is living. Consider Japan’s largest online retailer, Rakuten, Inc. It mandated that English will be the standard language by March 2012.Jeff Thredgold, “English Is Increasingly the International Language of Business,” Deseret News, December 14, 2010, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.deseretnews.com/article/700091766/English-is-increasingly-the-international-language-of-business.html. Other employers, such as Nissan and Sony, have made similar mandates or have already implemented an English-only policy. Despite this, a large percentage of your employee’s time will be spent outside work, where mastery of the language is important to enjoy living in another country. In addition, being able to discuss and negotiate in the mother tongue of the country can give your employee greater advantages when working on an overseas assignment. Part of language, as we discussed in Chapter 9, isn’t only about what you say but also includes all the nonverbal aspects of language. Consider the following examples:

- In the United States, we place our palm upward and use one finger to call someone over. In Malaysia, this is only used for calling animals. In much of Europe, calling someone over is done with palm down, making a scratching motion with the fingers (as opposed to one finger in the United States). In Columbia, soft handclaps are used.

- In many business situations in the United States, it is common to cross your legs, pointing the soles of your shoes to someone. In Southeast Asia, this is an insult since the feet are the dirtiest and lowest part of the body.

- Spatial differences are an aspect of nonverbal language as well. In the United States, we tend to stand thirty-six inches (an arm length) from people, but in Chile, for example, the space is much smaller.

- Proper greetings of business colleagues differ from country to country.

- The amount of eye contact varies. For example, in the United States, it is normal to make constant eye contact with the person you are speaking with, but in Japan it would be rude to make constant eye contact with someone with more age or seniority.

The goal of cultural training is to train employees what the “norms” are in a particular culture. Many of these norms come from history, past experience, and values. Cultural training can include any of the following topics:

- Etiquette

- Management styles

- History

- Religion

- The arts

- Food

- Geography

- Logistics aspects, such as transportation and currency

- Politics

Cultural training is important. Although cultural implications are not often discussed openly, not understanding the culture can harm the success of a manager when on overseas assignment. For example, when Revlon expanded its business into Brazil, one of the first products it marketed was a Camellia flower scented perfume. What the expatriate managers didn’t realize is that the Camellia flower is used for funerals, so of course, the product failed in that country.Sudipta Roy, “Brand Failures: A Consumer Perspective to Formulate a MNC Entry Strategy” (postgraduate diploma, XLRI School of Business and Human Resources, 1998), accessed August 12, 2011, http://sudiptaroy.tripod.com/dissfin.pdf. Cultural implications, such as management style, are not always so obvious. Consider the US manager who went to Mexico to manage a production line. He applied the same management style that worked well in America, asking a lot of questions and opinions of employees. When employees started to quit, he found out later that employees expect managers to be the authority figure, and when the manager asked questions, they assumed he didn’t know what he was doing.

Training on the goals and expectations for the expatriate worker is important. Since most individuals take an overseas assignment to boost their careers, having clear expectations and understanding of what they are expected to accomplish sets the expatriate up for success.

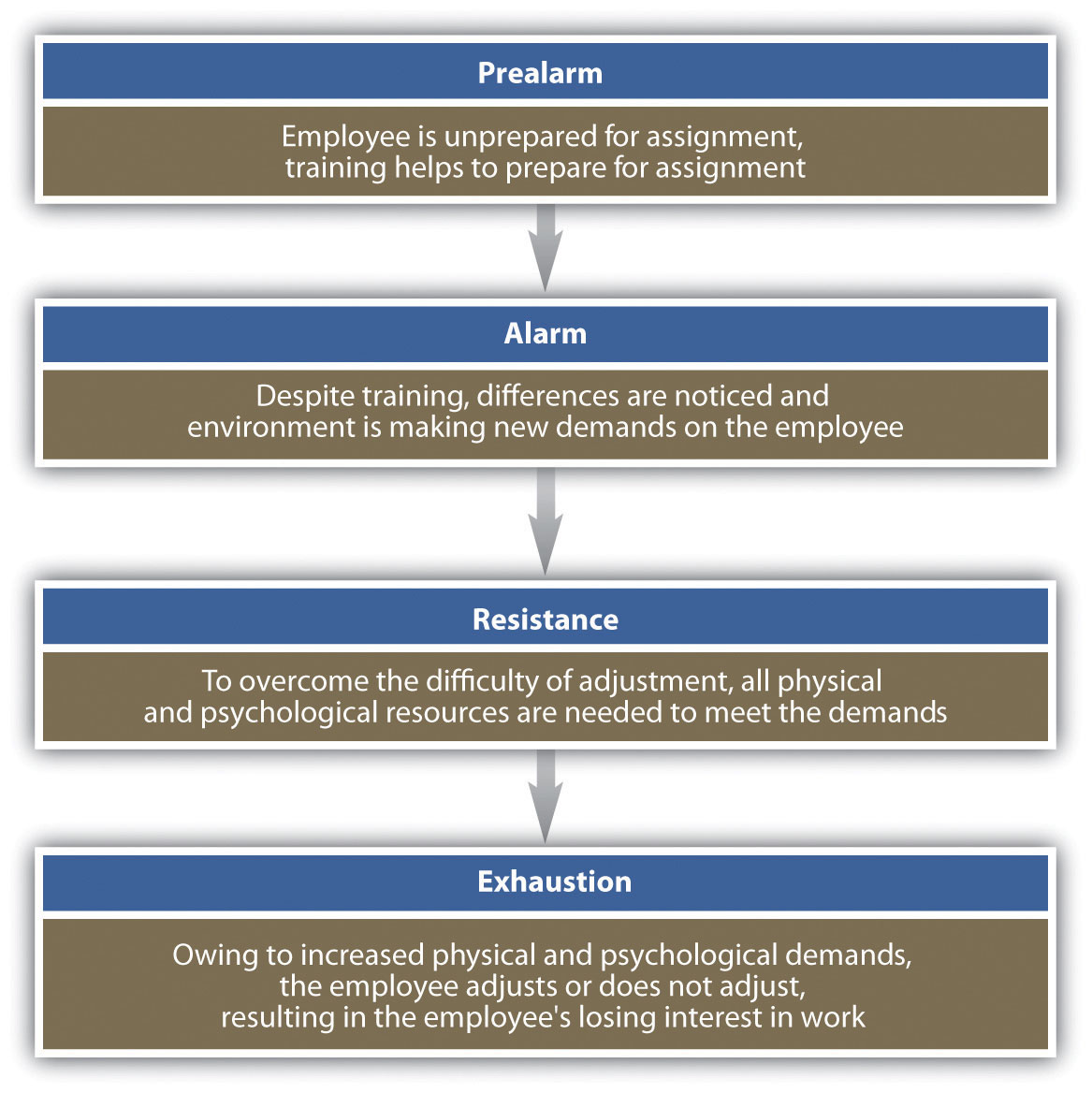

Because moving to a new place, especially a new country, is stressful, it is important to train the employee on managing stress, homesickness, culture shock, and likely a larger workload than the employee may have had at home. Some stress results from insecurity and homesickness. It is important to note that much of this stress occurs on the family as well. The expatriate may be performing and adjusting well, but if the family isn’t, this can cause greater stress on the employee, resulting in a failed assignment. Four stages of expatriate stress identified in the Selyes model, the General Adaption Syndrome, are shown in Figure 14.5 "General Adaption Syndrome to Explain Expatriate Stress". The success of overseas employees depends greatly on their ability to adjust, and training employees on the stages of adjustment they will feel may help ease this problem.

Cultural Differences

(click to see video)These two videos discuss practical implications of cultural differences.

Figure 14.5 General Adaption Syndrome to Explain Expatriate Stress

Source: Bala Koteswari and Mousumi Bhattacharya, “Managing Expatriate Stress,” Delhi Business Review 8, no. 1 (2007): 89–98.

Spouses and children of the employee may also experience much of the stress the expatriate feels. Children’s attendance at new schools and lack of social networks, as well as possible sacrifice of a spouse’s career goal, can negatively impact the assignment. Many companies offer training not only for the employee but for the entire family when engaging in an overseas assignment. For example, global technology and manufacturing company Honeywell offers employees and their families a two-day cultural orientation on the region they will be living in.Leslie Gross Klaff, “The Right Way to Bring Expats Home,” BNET, July 2002, accessed August 12, 2011, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FXS/is_7_81/ai_89269493/. Some of the reasons for lack of adjustment by family members might include the following:

- Language issues

- Social issues

- Schooling

- Housing

- Medical services

The ability of the organization to meet these family needs makes for a more successful assignment. For example, development of an overseas network to provide social outlets, activities, schooling and housing options, assignment of mentors to the spouse, and other methods can help ease the transition.

Finally, repatriationThe process of helping employees make the transition to their home country. is the process of helping employees make the transition to their home country. Many employees experience reverse culture shockRefers to the psychological phenomenon that can lead to feelings of fear, helplessness, irritability, and disorientation when an expatriate returns home. upon returning home, which is a psychological phenomenon that can lead to feelings of fear, helplessness, irritability, and disorientation. All these factors can cause employees to leave the organization soon after returning from an assignment, and to take their knowledge with them. One problem with repatriation is that the expatriate and family have assumed things stayed the same at home, while in fact friends may have moved, friends changed, or new managers may have been hired along with new employees. Although the manager may be on the same level as other managers when he or she returns, the manager may have less informal authority and clout than managers who have been working in the particular office for a period of time. An effective repatriation program can cost $3,500 to $10,000 per family, but the investment is worth it given the critical skills the managers will have gained and can share with the organization. In fact, many expatriates fill leadership positions within organizations, leveraging the skills they gained overseas. One such example is FedEx president and CEO David Bronczek and executive vice president Michael Drucker. Tom Mullady, the manager of international compensation planning at FedEx, makes the case for a good repatriation program when he says, “As we become more and more global, it shows that experience overseas is leveraged back home.” Leslie Gross Klaff, “The Right Way to Bring Expats Home,” BNET, July 2002, accessed August 12, 2011, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FXS/is_7_81/ai_89269493/

Repatriation planning should happen before the employee leaves on assignment and should be a continuous process throughout the assignment and upon return. The process can include the following:

- Training and counseling on overseas assignment before leaving

- Clear understanding of goals before leaving, so the expatriate can have a clear sense as to what new skills and knowledge he or she will bring back home

- Job guarantee upon return (Deloitte and Touche, for example, discusses which job each of the two hundred expats will take after returning, before the person leaves, and offers a written letter of commitment.Leslie Gross Klaff, “The Right Way to Bring Expats Home,” BNET, July 2002, accessed August 12, 2011, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FXS/is_7_81/ai_89269493/)

- Assigning the expatriate a mentor, ideally a former expatriate

- Keeping communication from home open, such as company newsletters and announcements

- Free return trips home to stay in touch with friends and family

- Counseling (at Honeywell, employees and families go through a repatriation program within six months of returning.Leslie Gross Klaff, “The Right Way to Bring Expats Home,” BNET, July 2002, accessed August 12, 2011, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FXS/is_7_81/ai_89269493/)

- Sponsoring brown bag lunches where the expatriate can discuss what he or she learned while overseas

- Trying to place expatriates in positions where they can conduct business with employees and clients from where they lived

It is also important to note that offering an employee an international assignment can help develop that person’s understanding of the business, management style, and other business-related development. Working overseas can be a crucial component to succession planning. It can also be a morale booster for other employees, who see that the chosen expatriate is further able to develop his or her career within the organization.

While the focus of this section has been on expatriate assignments, the same information on training is true for third-country nationals.

If it is decided that host-country nationals will be hired, different training considerations might occur. For example, will they spend some time at your domestic corporate headquarters to learn the business, then apply what they learned when they go home? Or, does it make more sense to send a domestic manager overseas to train the host-country manager and staff? Training will obviously vary based on the type of business and the country, and it may make sense to gain input from host-country managers as opposed to developing training on your own. As we have already discussed in this chapter, an understanding of the cultural components is the first step to developing training that can be utilized in any country.

Compensation and Rewards

There are a few options when choosing compensation for a global business. The first option is to maintain companywide pay scales and policies, so for example, all sales staff are paid the same no matter what country they are in. This can reduce inequalities and simplify recording keeping, but it does not address some key issues. First, this compensation policy does not address that it can be much more expensive to live in one place versus another. A salesperson working in Japan has much higher living expenses than a salesperson working in Peru, for example. As a result, the majority of organizations thus choose to use a pay banding system based on regions, such as South America, Europe, and North America. This is called a localized compensation strategyA international compensation strategy that uses regional or local cost-of-living information to pay employees.. Microsoft and Kraft Foods both use this approach. This method provides the best balance of cost-of-living considerations.

However, regional pay banding is not necessarily the ideal solution if the goal is to motivate expatriates to move. For example, if the employee has been asked to move from Japan to Peru and the salary is different, by half, for example, there is little motivation for that employee to want to take an assignment in Peru, thus limiting the potential benefits of mobility for employees and for the company.

One possible option is to pay a similar base salary companywide or regionwide and offer expatriates an allowance based on specific market conditions in each country.J. Cartland, “Reward Policies in a Global Corporation,” Business Quarterly, Autumn 1993, 93–96. This is called the balance sheet approachExpatriates are offered a similar base salary companywide or region wide and are given an allowance based on specific market conditions in each country.. With this compensation approach, the idea is that the expatriate should have the same standard of living that he or she would have had at home. Four groups of expenses are looked at in this approach:

- Income taxes

- Housing

- Goods and services

- Base salary

- Overseas premium

The HR professional would estimate these expenses within the home country and costs for the same items in the host country. The employer then pays differences. In addition, the base salary will normally be in the same range as the home-country salary, and an overseas premiumAn extra amount paid to an expatriate for accepting an overseas assignment. might be paid owing to the challenge of an overseas assignment. An overseas premium is an additional bonus for agreeing to take an overseas assignment. There are many companies specializing in cost-of-living data, such as Mercer Reports. It provides cost-of-living information at a cost of $600 per year. Table 14.6 "The Balance Sheet Approach to Compensation" shows a hypothetical example of how the balance sheet approach would work.

Table 14.6 The Balance Sheet Approach to Compensation

| Chicago, IL | Tokyo | Allowance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax rate | 30% | 35% | 5% or $288/month |

| Housing | $1250 | $1800 | $550 |

| Base salary | $5400 | $5,750 | $350 |

| Overseas premium | 15% | $810 | |

| Total allowance | $1998 | ||

| Total salary and allowance | $5400 | $7748 |

Other compensation issues, which will vary greatly from country to country, might include the following:

- The cost of benefits in another country. Many countries offer universal health care (offset by higher taxes), and therefore the employee would have health benefits covered while working and paying taxes in that country. Canada, Finland, and Japan are examples of countries that have this type of coverage. In countries such as Singapore, all residents receive a catastrophic policy from the government, but they need to purchase additional insurance for routine care.Countries with Universal Healthcare (no date), accessed August 11, 2011, http://truecostblog.com/2009/08/09/countries-with-universal-healthcare-by-date/. A number of organizations offer health care for expatriates relocating to another country in which health care is not already provided.

- Legally mandated (or culturally accepted) amount of vacation days. For example, in Australia twenty paid vacation days are required, ten in Canada, thirty in Finland, and five in the Philippines. The average number of US worker vacation days is fifteen, although the number of days is not federally mandated by the government, as with the other examples.Jeanne Sahadi, “Who Gets the Most (and Least) Vacation” CNN Money, June 14, 2007, accessed August 11, 2011, http://money.cnn.com/2007/06/12/pf/vacation_days_worldwide/.

- Legal requirements of profit sharing. For example, in France, the government heavily regulates profit sharing programs.Wilke, Maack, und Partner, “Profit-Sharing,” Country Reports on Financial Participation in Europe, 2007, worker-participation.eu, 2007, accessed August 12, 2011, http://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations/Across-Europe/Financial-Participation/Profit-sharing.

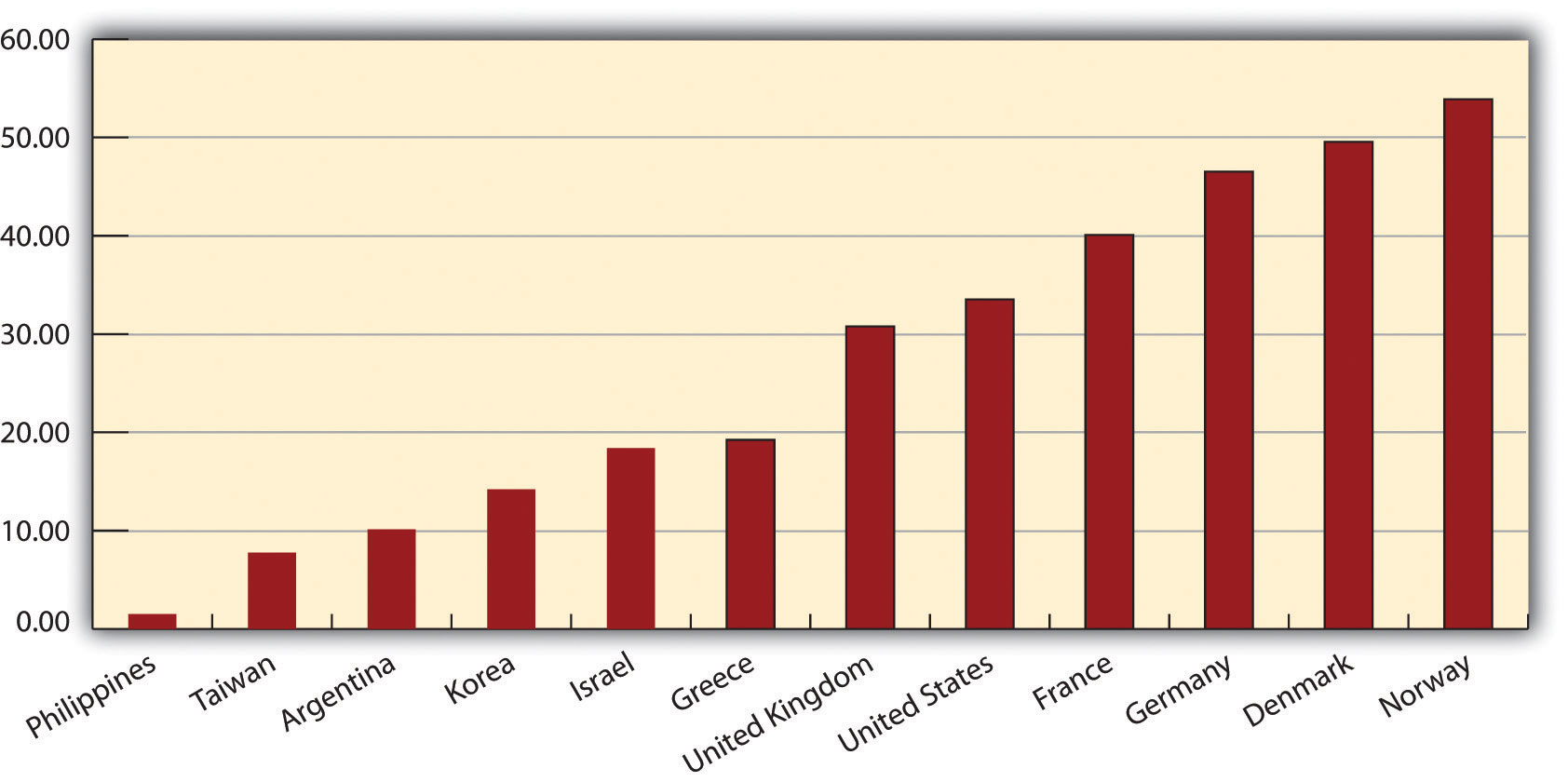

- Pay system that works with the country culture, such as pay systems based on seniority. For example, Chinese culture focuses heavily on seniority, and pay scales should be developed according to seniority. In Figure 14.6 "Hourly World Compensation Comparisons for Manufacturing Jobs", examples of hourly compensation for manufacturing workers are compared.

- Thirteenth month (bonus) structures and expected (sometimes mandated) annual lump-sum payments. Compensation issues are a major consideration in motivating overseas employees. A systematic system should be in place to ensure fairness in compensation for all expatriates.

Figure 14.6 Hourly World Compensation Comparisons for Manufacturing Jobs

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Division of International Labor Comparisons, International Comparisons of Hourly Compensation costs in Manufacturing, 2009, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ichcc.toc.htm (accessed September 16, 2011).

Performance Evaluations

The challenge in overseas performance evaluations is determining who should rate the performance of the expatriate. While it might make sense to have the host-country employees and managers rate the expatriate, cultural differences may make this process ineffective. Cultural challenges may make the host country rate the expatriate more harshly, or in some cases, such as Indonesia, harmony is more important than productivity, so it may be likely an Indonesia employee or manager rates the expatriate higher, to keep harmony in the workplace.George Whitfield, “Do as I Say, Not as I Do: Annual Performance Appraisal and Evaluation in Indonesia” n.d., Living in Indonesia, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.expat.or.id/business/annualperformanceappraisal.html.

If the home-country manager rates the performance of the expatriate, he or she may not have a clear indication of the performance, since the manager and expatriate do not work together on a day-to-day basis. A study performed by Gregersen, Hite, and Black suggests that a balanced set of raters from host and home countries and more frequent appraisals relate positively to the accuracy of performance evaluations.Hal Gregersen, Julie Hite, and Steward Black, “Expatriate Performance Appraisal in US Multinational Firms,” Journal of International Business Studies 27, no. 4 (1996): 711–38. They also suggest that the use of a standardized form relates negatively to perceived accuracy. Carrie Shearer, an international HR expert, concurs by stating that the standardized form, if used, should also include special aspects for the expatriate manager, such as how well the expatriate fits in with the culture and adaptation ability.Carrie Shearer, “Expat Performance Appraisal: A Two Tier Process?” October 8, 2004, Expatrica.com, accessed August 12, 2011, http://www.expatica.com/hr/story/expat-performance-appraisal-a-two-tier-process-10529.html.

Besides determining who should rate the expatriate’s performance, the HR professional should determine the criteria for evaluating the expatriate. Since it is likely the expatriate’s job will be different overseas, the previous criteria used may not be helpful in the evaluation process. The criteria used to rate the performance should be determined ahead of time, before the expatriate leaves on assignment. This is part of the training process we discussed earlier. Having a clear picture of the rating criteria for an overseas assignment makes it both useful for the development of the employee and for the organization as a tool. A performance appraisal also offers a good opportunity for the organization to obtain feedback about how well the assignment is going and to determine whether enough support is being provided to the expatriate.

The International Labor Environment

As we have already alluded to in this chapter, understanding of laws and how they relate to host-country employees and expatriates can vary from country to country. Because of this, individual research on laws in the specific countries is necessary to ensure adherence:

- Worker safety laws

- Worker compensation laws

- Safety requirements

- Working age restrictions

- Maternity/paternity leaves

- Unionization laws

- Vacation time requirements

- Average work week hours

- Privacy laws

- Disability laws

- Multiculturalism and diverse workplace, antidiscrimination law

- Taxation

As you can tell from this list, the considerable HRM factors when doing business overseas should be thoroughly researched.

One important factor worth mentioning here is labor unions. As you remember from Chapter 12 "Working with Labor Unions", labor unions have declined in membership in the United States. Collective bargaining is the process of developing an employment contract between a union and management within an organization. The process of collective bargaining can range from little government involvement to extreme government involvement as in France, for example, where some of the labor unions are closely tied with political parties in the country.

Some countries, such as Germany, engage in codeterminationThe practice and legal requirement of company shareholders’ and employees’ being represented in equal numbers on the boards of organizations., mandated by the government. Codetermination is the practice of company shareholders’ and employees’ being represented in equal numbers on the boards of organizations, for organizations with five hundred or more employees. The advantage of this system is the sharing of power throughout all levels of the organization; however, some critics feel it is not the place of government to tell companies how their corporation should be run. The goal of such a mandate is to reduce labor conflict issues and increase bargaining power of workers.

Taxation of expatriates is an important aspect of international HRM. Of course, taxes are different in every country, and it is up to the HR professional to know how taxes will affect the compensation of the expatriate. The United States has income tax treaties with forty-two countries, meaning taxing authorities of treaty countries can share information (such as income and foreign taxes paid) on residents living in other countries. US citizens must file a tax return, even if they have not lived in the United States during the tax year. US taxpayers claim over $90 billion in foreign tax credits on a yearly basis.Internal Revenue Service, “Foreign Tax Credit,” accessed August 13, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/businesses/article/0,,id=183263,00.html. Foreign tax creditsA tax credit in the United States that allows expatriates working abroad to claim taxes paid overseas on their US tax forms, reducing or eliminating double taxation. allow expatriates working abroad to claim taxes paid overseas on their US tax forms, reducing or eliminating double taxation. Many organizations with expatriate workers choose to enlist the help of tax accountants for their workers to ensure workers are paying the correct amount of taxes both abroad and in the United States.

Table 14.7 Examples of HRM-Related Law Differences between the United States and China

| United States | China* | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Contracts | Most states have at-will employment | Contract employment system. All employees must have a written contract |

| Layoffs | No severance required | Company must be on verge of bankruptcy before it can lay off employees |

| Two years of service required to pay severance; more than five years of experience requires a long service payment | ||

| Termination | Employment at will | Employees can only be terminated for cause, and cause must be clearly proved. They must be given 30 days’ notice, except in the case of extreme circumstances, like theft |

| Overtime | None required for salaried employees | Employees who work more than 40 hours must be paid overtime |

| Salary | Up to individual company | A 13-month bonus is customary, but not required, right before the Chinese New Year |

| Vacation | No governmental requirement | Mandated by government: |