This is “Staffing Internationally”, section 14.2 from the book Beginning Management of Human Resources (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.2 Staffing Internationally

Learning Objectives

- Be able to explain the three staffing strategies for international businesses and the advantages and disadvantages for each.

- Explain the reasons for expatriate failures.

One of the major decisions for HRM when a company decides to operate overseas is how the overseas operation will be staffed. This is the focus of this section.

Types of Staffing Strategy

There are three main staffing strategies a company can implement when entering an overseas market, with each having its advantages and disadvantages. The first strategy is a home-country national strategyThis staffing strategy uses employees from the home country to live and work in the country.. This staffing strategy uses employees from the home country to live and work in the country. These individuals are called expatriatesAn employee from the home country who is on international assignment in another country.. The second staffing strategy is a host-country national strategyTo employ people who were born in the country in which the business is operating., which means to employ people who were born in the country in which the business is operating. Finally, a third-country national strategy means to employee people from an entirely different country from the home country and host country. Table 14.4 "Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Staffing Strategies" lists advantages and disadvantages of each type of staffing strategy. Whichever strategy is chosen, communication with the home office and strategic alignment with overseas operations need to occur for a successful venture.

Table 14.4 Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Staffing Strategies

| Home-Country National | Host-Country National | Third-Country National | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Greater control of organization | Language barrier is eliminated | The third-country national may be better equipped to bring the international perspective to the business |

| Managers gain experience in local markets | Possible better understanding of local rules and laws | Costs associated with hiring such as visas may be less expensive than with home-country nationals | |

| Possible greater understanding and implementation of business strategy | Hiring costs such as visas are eliminated | ||

| Cultural understanding | |||

| Morale builder for employees of host country | |||

| Disadvantages | Adapting to foreign environment may be difficult for manager and family, and result in less productivity | Host-country manager may not understand business objectives as well without proper training | Must consider traditional national hostilities |

| Expatriate may not have cultural sensitivity | May create a perception of “us” versus “them” | The host government and/or local business may resent hiring a third-country national | |

| Language barriers | Can affect motivation of local workers | ||

| Cost of visa and hiring factors |

Human Resource Recall

Compare and contrast a home-country versus a host-country staffing strategy.

Expatriates

According to Simcha Ronen, a researcher on international assignments, there are five categories that determine expatriate success. They include job factors, relational dimensions, motivational state, family situation, and language skills. The likelihood the assignment will be a success depends on the attributes listed in Table 14.5 "Categories of Expatriate Success Predictors with Examples". As a result, the appropriate selection process and training can prevent some of these failings. Family stress, cultural inflexibility, emotional immaturity, too much responsibility, and longer work hours (which draw the expatriate away from family, who could also be experiencing culture shock) are some of the reasons cited for expatriate failure.

Table 14.5 Categories of Expatriate Success Predictors with Examples

| Job Factors | Relational Dimensions | Motivational State | Family Situation | Language Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical skills | Tolerance for ambiguity | Belief in the mission | Willingness of spouse to live abroad | Host-country language |

| Familiarity with host country and headquarters operations | Behavioral flexibility | Congruence with career path | Adaptive and supportive spouse | Nonverbal communication |

| Managerial skills | Nonjudgmentalism | Interest in overseas experience | Stable marriage | |

| Administrative competence | Cultural empathy and low ethnocentrism | Interest in specific host-country culture | ||

| Interpersonal skills | Willingness to acquire new patterns of behavior and attitudes |

Source: Adapted from Simcha Ronen, Training the International Assignee (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1989), 426–40.

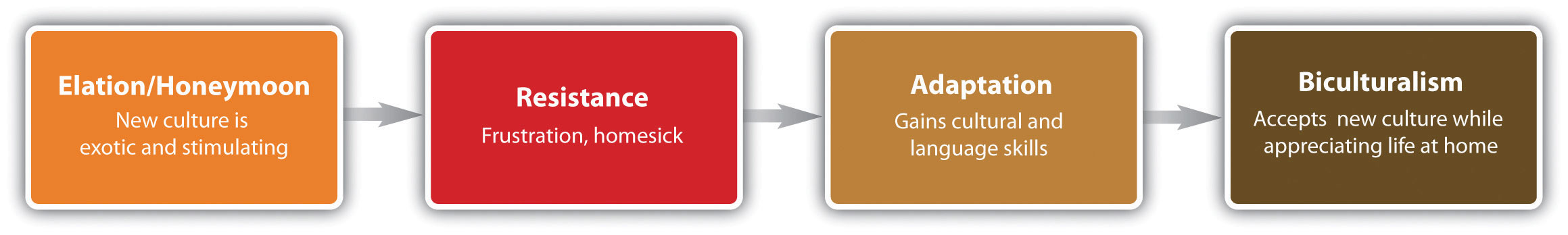

Most expatriates go through four phases of adjustment when they move overseas for an assignment. They include elation/honeymoonA phase of expatriate adjustment; the employee is excited about the new surroundings and finds the culture exotic and stimulating., resistanceA phase of expatriate adjustment; the employee may start to make frequent comparisons between home and host country and may seek out reminders of home. Frustration may occur because of everyday living, such as language and cultural differences., adaptionA phase of expatriate adjustment; the employee gains language skills and starts to adjust to life overseas. Sometimes during this phase expatriates may even tend to reject their own culture. In this phase, the expatriate is embracing life overseas., and biculturalismA phase of expatriate adjustment; the expatriate embraces the new culture and begins to appreciate his old life at home as much as his new life overseas. Many of the problems associated with expatriate failures, such as family life and cultural stress, have diminished.. In the elation phase, the employee is excited about the new surroundings and finds the culture exotic and stimulating. In the resistance phase, the employee may start to make frequent comparisons between home and host country and may seek out reminders of home. Frustration may occur because of everyday living, such as language and cultural differences. During the adaptation phase, the employee gains language skills and starts to adjust to life overseas. Sometimes during this phase, expatriates may even tend to reject their own culture. In this phase, the expatriate is embracing life overseas. In the last phase, biculturalism, the expatriate embraces the new culture and begins to appreciate his old life at home equally as much as his new life overseas. Many of the problems associated with expatriate failures, such as family life and cultural stress, have diminished.

Figure 14.2 Phases of Expatriate Adjustment

Host-Country National

The advantage, as shown in Table 14.4 "Advantages and Disadvantages of the Three Staffing Strategies", of hiring a host-country national can be an important consideration when designing the staffing strategy. First, it is less costly in both moving expenses and training to hire a local person. Some of the less obvious expenses, however, may be the fact that a host-country national may be more productive from the start, as he or she does not have many of the cultural challenges associated with an overseas assignment. The host-country national already knows the culture and laws, for example. In Russia, 42 percent of respondents in an expatriate survey said that companies operating there are starting to replace expatriates with local specialists. In fact, many of the respondents want the Russian government to limit the number of expatriates working for a company to 10 percent.“Russia Starts to Abolish Expat jobs,” Expat Daily, April 27, 2011, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.expat-daily.com/news/russia-starts-to-abolish-expat-jobs/. When globalization first occurred, it was more likely that expatriates would be sent to host countries, but in 2011, many global companies are comfortable that the skills, knowledge, and abilities of managers exist in the countries in which they operate, making the hiring of a host-country national a favorable choice. Also important are the connections the host-country nationals may have. For example, Shiv Argawal, CEO of ABC Consultants in India, says, “An Indian CEO helps influence policy and regulations in the host country, and this is the factor that would make a global company consider hiring local talent as opposed to foreign talent.”Divya Rajagorpal and MC Govardhanna Rangan, “Global Firms Prefer Local Executives to Expats to Run Indian Operation,” Economic Times, April 20, 2011, accessed September 15, 2011, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2011-04-20/news/29450955_1_global-firms-joint-ventures-investment-banking.

Third-Country Nationals

One of the best examples of third-country nationals is the US military. The US military has more than seventy thousand third-country nationals working for the military in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan. For example, a recruitment firm hired by the US military called Meridian Services Agency recruits hairstylists, construction workers, and electricians from all over the world to fill positions on military bases.Sarah Stillman, “The Invisible Army,” New Yorker, June 6, 2011, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/06/06/110606fa_fact_stillman. Most companies who utilize third-country national labor are not new to multinational businesses. The majority of companies who use third-country national staffing have many operations already overseas. One example is a multinational company based in the United States that also has operations in Spain and transfers a Spanish manager to set up new operations in Argentina. This would be opposed to the company in the United States sending an American (expatriate) manager to Argentina. In this case, the third-country national approach might be the better approach because of the language aspect (both Spain and Argentina speak Spanish), which can create fewer costs in the long run. In fact, many American companies are seeing the value in hiring third-country nationals for overseas assignments. In an International Assignments Survey,“More Third Country Nationals Being Used,” n.d., SHRM India, accessed August 11, 2011, http://www.shrmindia.org/more-third-country-nationals-being-used. 61 percent of United States–based companies surveyed increased the use of third-country nationals by 61 percent, and of that number, 35 percent have increased the use of third-country nationals to 50 percent of their workforce. The main reason why companies use third-country nationals as a staffing strategy is the ability of a candidate to represent the company’s interests and transfer corporate technology and competencies. Sometimes the best person to do this isn’t based in the United States or in the host country.

Key Takeaways

- There are three types of staffing strategies for an international business. First, in the home-country national strategy, people are employed from the home country to live and work in the country. These individuals are called expatriates. One advantage of this type of strategy is easier application of business objectives, although an expatriate may not be culturally versed or well accepted by the host-country employees.

- In a host-country strategy, workers are employed within that country to manage the operations of the business. Visas and language barriers are advantages of this type of hiring strategy.

- A third-country national staffing strategy means someone from a country, different from home or host country, will be employed to work overseas. There can be visa advantages to using this staffing strategy, although a disadvantage might be morale lost by host-country employees.

Exercises

- Choose a country you would enjoy working in, and visit that country’s embassy page. Discuss the requirements to obtain a work visa in that country.

- How would you personally prepare an expatriate for an international assignment? Perform additional research if necessary and outline a plan.