This is “Hotelling Differentiation”, section 17.3 from the book Beginning Economic Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

17.3 Hotelling Differentiation

Learning Objective

- What are the types of differentiated products and how do firms selling differentiated products behave?

Breakfast cereals range from indigestible, unprocessed whole grains to boxes that are filled almost entirely with sugar, with only the odd molecule or two of grain thrown in. Such cereals are hardly good substitutes for each other. Yet similar cereals are viewed by consumers as good substitutes, and the standard model of this kind of situation is the Hotelling model.Hotelling theory is named for Harold Hotelling (1895–1973). Hotelling was the first to use a line segment to represent both the product that is sold and the preferences of the consumers who are buying the products. In the Hotelling modelModel of imperfect competition in which customers’ preferences and products are located by points on the same line segment., customers' preferences are located by points on the same line segment. The same line is used to represent products. For example, movie customers are differentiated by age, and we can represent moviegoers by their ages. Movies, too, are designed to be enjoyed by particular ages. Thus, a preteen movie is unlikely to appeal very much to a 6-year-old or to a 19-year-old, while a Disney movie appeals to a 6-year-old, but less to a 15-year-old. That is, movies have a target age, and customers have ages, and these are graphed on the same line.

Figure 17.1 Hotelling Model for Breakfast Cereals

Breakfast cereal is a classic application of the Hotelling line, and this application is illustrated in Figure 17.1 "Hotelling Model for Breakfast Cereals". Breakfast cereals are primarily distinguished by their sugar content, which ranges on the Hotelling line from low on the left to high on the right. Similarly, the preferences of consumers also fall on the same line. Each consumer has a “most desired point,” and he or she prefers cereals closer to that point than cereals at more distant points.

There are two main types of differentiation, each of which can be modeled using the Hotelling line. These types are quality and variety. Quality refers to a situation where consumers agree on which product is better; the disagreement among consumers concerns whether higher quality is worth the cost. In automobiles, faster acceleration, better braking, higher gas mileage, more cargo space, more legroom, and greater durability are all good things. In computers, faster processing, brighter screens, higher resolution screens, lower heat, greater durability, more megabytes of RAM, and more gigabytes of hard drive space are all good things. In contrast, varieties are the elements about which there is not widespread agreement. Colors and shapes are usually varietal rather than quality differentiators. Some people like almond-colored appliances, others choose white, with blue a distant third. Food flavors are varieties, and while the quality of ingredients is a quality differentiator, the type of food is usually a varietal differentiator. Differences in music would primarily be varietal.

Quality is often called vertical differentiationQuality., while variety is horizontal differentiationVariety..

The standard Hotelling model fits two ice cream vendors on a beach. The vendors sell an identical product, and they can choose to locate wherever they wish. For the time being, suppose the price they charge for ice cream is fixed at $1. Potential customers are also spread randomly along the beach.

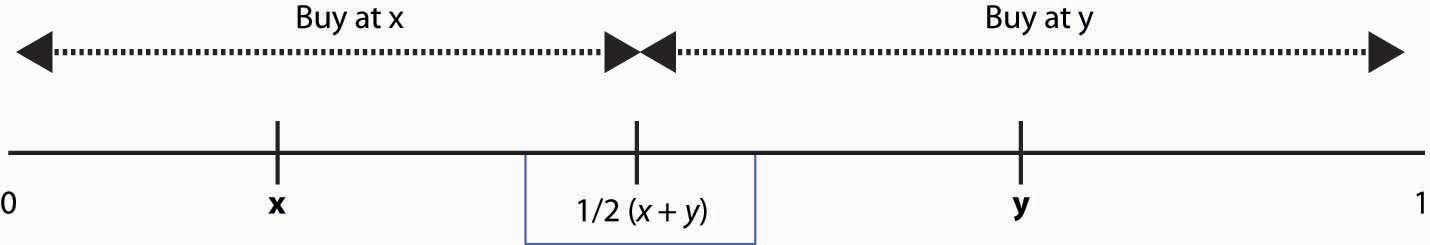

We let the beach span an interval from 0 to 1. People desiring ice cream will walk to the closest vendor because the price is the same. Thus, if one vendor locates at x and the other at y, and x < y, those located between 0 and ½ (x + y) go to the left vendor, while the rest go to the right vendor. This is illustrated in Figure 17.2 "Sharing the Hotelling Market".

Figure 17.2 Sharing the Hotelling Market

Note that the vendor at x sells more by moving toward y, and vice versa. Such logic forces profit-maximizing vendors to both locate in the middle. The one on the left sells to everyone left of ½, while the one on the right sells to the rest. Neither can capture more of the market, so equilibrium locations have been found. (To complete the description of an equilibrium, we need to let the two “share” a point and still have one on the right side and one on the left side of that point.)

This solution is commonly used as an explanation of why U.S. political parties often seem very similar to each other—they have met in the middle in the process of chasing the most voters. Political parties can’t directly buy votes, so the “price” is fixed; the only thing parties can do is locate their platform close to voters’ preferred platform, on a scale of “left” to “right.” But the same logic that a party can grab the middle, without losing the ends, by moving closer to the other party will tend to force the parties to share the same middle-of-the-road platform.

The model with constant prices is unrealistic for the study of the behavior of firms. Moreover, the two-firm model on the beach is complicated to solve and has the undesirable property that it matters significantly whether the number of firms is odd or even. As a result, we will consider a Hotelling model on a circle and let the firms choose their prices.

Key Takeaways

- In the Hotelling model, there is a line, and the preferences of each consumer are represented by a point on this line. The same line is used to represent products.

- There are two main types of differentiation: quality and variety. Quality refers to a situation where consumers agree on which product is better. Varieties are the differentiators about which there is not widespread agreement.

- Quality is often called vertical differentiation, while variety is horizontal differentiation.

- The standard Hotelling model involves two vendors selling an identical product and choosing to locate on a line. Both charge the same price. People along the line buy from the closest vendor.

- The Nash equilibrium for the standard model involves both sellers locating in the middle. This is inefficient because it doesn’t minimize transport costs.

- The standard model is commonly used as a model to represent the positions of political candidates.

Exercise

- Suppose there are four ice cream vendors on the beach, and customers are distributed uniformly. Show that it is a Nash equilibrium for two to locate at ¼ and two to locate at ¾.