This is “Examples”, section 16.4 from the book Beginning Economic Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

16.4 Examples

Learning Objective

- How can game theory be applied to the economic settings?

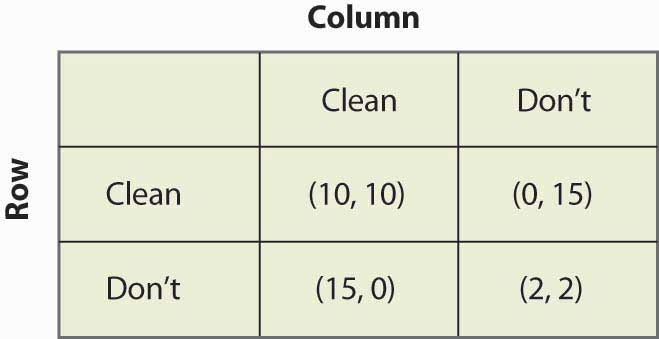

Our first example concerns public goods. In this game, each player can either contribute or not. For example, two roommates can either clean their apartment or not. If they both clean, the apartment is nice. If one cleans, then that roommate does all of the work and the other gets half of the benefits. Finally, if neither cleans, neither is very happy. This suggests the following payoffs as shown in Figure 16.21 "Cleaning the apartment".

Figure 16.21 Cleaning the apartment

You can verify that this game is similar to the prisoner’s dilemma in that the only Nash equilibrium is the pure strategy in which neither player cleans. This is a game-theoretic version of the tragedy of the commons—even though both roommates would be better off if both cleaned, neither do. As a practical matter, roommates do solve this problem, using strategies that we will investigate when we consider dynamic games.

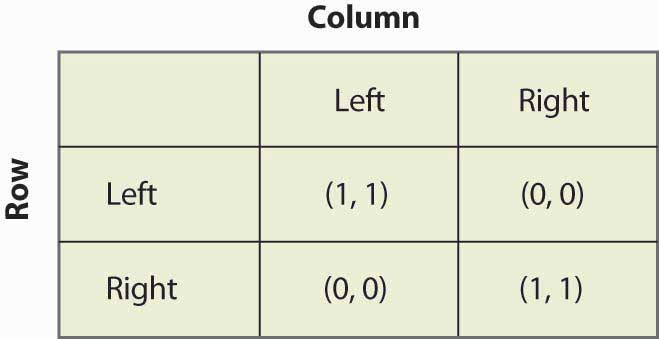

Figure 16.22 Driving on the right

As illustrated in Figure 16.22 "Driving on the right", in the “driving on the right” game, the important consideration about which side of the road that cars drive on is not necessarily the right side but the same side. If both players drive on the same side, then they each get one point; otherwise, they get zero. You can readily verify that there are two pure strategy equilibria, (Left, Left) and (Right, Right), and a mixed strategy equilibrium with equal probabilities. Is the mixed strategy reasonable? With automobiles, there is little randomization. On the other hand, people walking down hallways often seem to randomize, whether they pass on the left or the right, and sometimes do that little dance where they try to get past each other—one going left and the other going right, then both simultaneously reversing, unable to get out of each other’s way. That dance suggests that the mixed strategy equilibrium is not as unreasonable as it seems in the automobile application.Continental Europe drove on the left side of the road until about the time of the French Revolution. At that time, some individuals began driving on the right as a challenge to royalty, who were on the left, essentially playing the game of chicken with the ruling class. Driving on the right became a symbol of disrespect for royalty. The challengers won out, forcing a shift to driving on the right. Besides which side one drives on, another coordination game involves whether one stops or goes on red. In some locales, the tendency for a few extra cars to proceed as a traffic light changes from green to yellow to red forces those whose light changes to green to wait; and such a progression can lead to the opposite equilibrium, where one goes on red and stops on green. Under Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese considered changing the equilibrium to proceeding on red and stopping on green (because “red is the color of progress”), but wiser heads prevailed and the plan was scrapped.

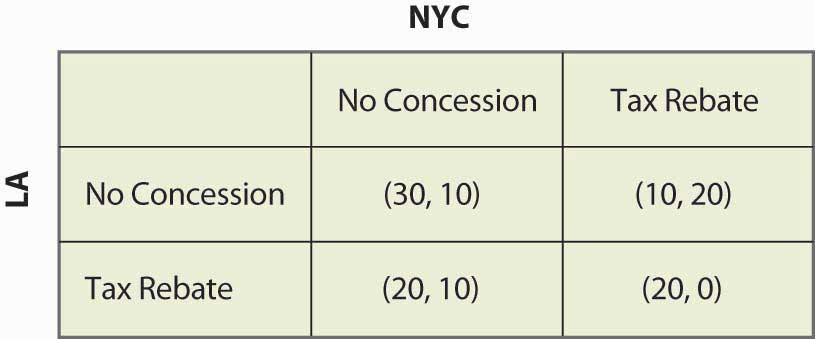

Figure 16.23 Bank location game

Consider a foreign bank that is looking to open a main office and a smaller office in the United States. As shown in Figure 16.23 "Bank location game", the bank narrows its choice for main office to either New York City (NYC) or Los Angeles (LA), and is leaning toward Los Angeles. If neither city does anything, Los Angeles will get $30 million in tax revenue and New York will get $10 million. New York, however, could offer a $10 million rebate, which would swing the main office to New York; but then New York would only get a net of $20 million. The discussions are carried on privately with the bank. Los Angeles could also offer the concession, which would bring the bank back to Los Angeles.

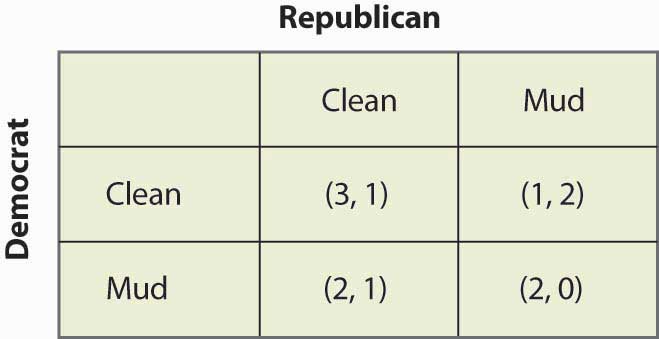

Figure 16.24 Political mudslinging

On the night before an election, a Democrat is leading the Wisconsin senatorial race. Absent any new developments, the Democrat will win and the Republican will lose. This is worth 3 to the Democrat; and the Republican, who loses honorably, values this outcome at 1. The Republican could decide to run a series of negative advertisements (“throwing mud”) against the Democrat and, if so, the Republican wins—although loses his honor, which he values at 1, and so only gets 2. If the Democrat runs negative ads, again the Democrat wins but loses his honor, so he only gets 2. These outcomes are represented in the mudslinging game shown in Figure 16.24 "Political mudslinging".

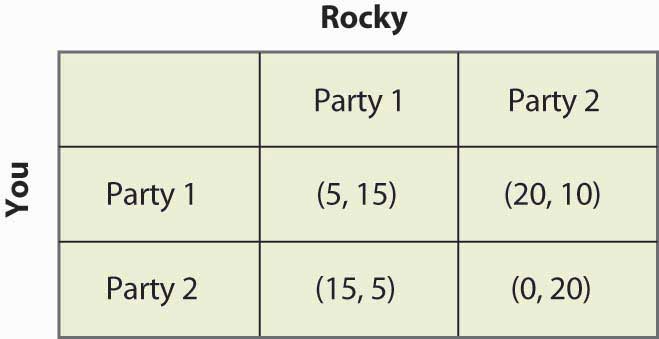

You have probably had the experience of trying to avoid encountering someone, whom we will call Rocky. In this instance, Rocky is actually trying to find you. Here it is Saturday night and you are choosing which party, of two possible parties, to attend. You like Party 1 better and, if Rocky goes to the other party, you get 20. If Rocky attends Party 1, you are going to be uncomfortable and get 5. Similarly, Party 2 is worth 15, unless Rocky attends, in which case it is worth 0. Rocky likes Party 2 better (these different preferences may be part of the reason why you are avoiding him), but he is trying to see you. So he values Party 2 at 10, Party 1 at 5, and your presence at the party he attends is worth 10. These values are reflected in Figure 16.25 "Avoiding Rocky".

Figure 16.25 Avoiding Rocky

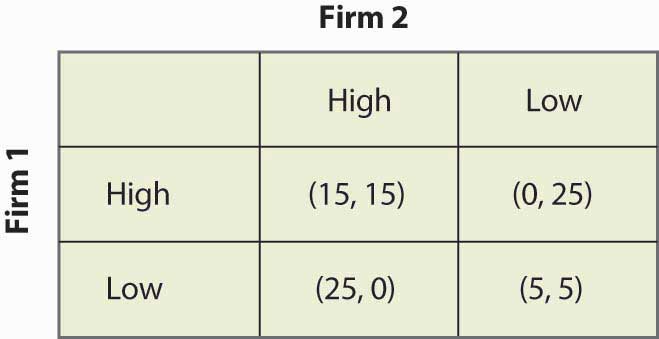

Our final example involves two firms competing for customers. These firms can either price High or Low. The most money is made if they both price High; but if one prices Low, it can take most of the business away from the rival. If they both price Low, they make modest profits. This description is reflected in Figure 16.26 "Price cutting game".

Figure 16.26 Price cutting game

Key Takeaways

- The free-rider problem of public goods with two players can be formulated as a game.

- Whether to drive on the right or the left is a game similar to battle of the sexes.

- Many everyday situations are reasonably formulated as games.

Exercises

- Verify that the bank location game has no pure strategy equilibria and that there is a mixed strategy equilibrium where each city offers a rebate with probability ½.

- Show that the only Nash equilibrium of the political mudslinging game is a mixed strategy with equal probabilities of throwing mud and not throwing mud.

- Suppose that voters partially forgive a candidate for throwing mud in the political mudslinging game when the rival throws mud, so that the (Mud, Mud) outcome has payoff (2.5, 0.5). How does the equilibrium change?

-

- Show that there are no pure strategy Nash equilibria in the avoiding Rocky game.

- Find the mixed strategy Nash equilibria.

- Show that the probability that you encounter Rocky is

- Show that the firms in the price-cutting game have a dominant strategy to price low, so that the only Nash equilibrium is (Low, Low).