This is “Effects of Taxes”, section 5.1 from the book Beginning Economic Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.1 Effects of Taxes

Learning Objective

- How do taxes affect equilibrium prices and the gains from trade?

Consider first a fixed, per-unit tax such as a 20-cent tax on gasoline. The tax could either be imposed on the buyer or the supplier. It is imposed on the buyer if the buyer pays a price for the good and then also pays the tax on top of that. Similarly, if the tax is imposed on the seller, the price charged to the buyer includes the tax. In the United States, sales taxes are generally imposed on the buyer—the stated price does not include the tax—while in Canada, the sales tax is generally imposed on the seller.

An important insight of supply and demand theory is that it doesn’t matter—to anyone—whether the tax is imposed on the supplier or the buyer. The reason is that ultimately the buyer cares only about the total price paid, which is the amount the supplier gets plus the tax; and the supplier cares only about the net to the supplier, which is the total amount the buyer pays minus the tax. Thus, with a a 20-cent tax, a price of $2.00 to the buyer is a price of $1.80 to the seller. Whether the buyer pays $1.80 to the seller and an additional 20 cents in tax, or pays $2.00, produces the same outcome to both the buyer and the seller. Similarly, from the seller’s perspective, whether the seller charges $2.00 and then pays 20 cents to the government, or charges $1.80 and pays no tax, leads to the same profit.There are two minor issues here that won’t be considered further. First, the party who collects the tax has a legal responsibility, and it could be that businesses have an easier time complying with taxes than individual consumers. The transaction costs associated with collecting taxes could create a difference arising from who pays the tax. Such differences will be ignored in this book. Second, if the tax is percentage tax, it won’t matter to the outcome; but the calculations are more complicated because a 10% tax on the seller at a seller’s price of $1.80 is different from a 10% tax on a buyer’s price of $2.00. Then the equivalence between taxes imposed on the seller and taxes imposed on the buyer requires different percentages that produce the same effective tax level. In addition, there is a political issue: Imposing the tax on buyers makes the presence and size of taxes more transparent to voters.

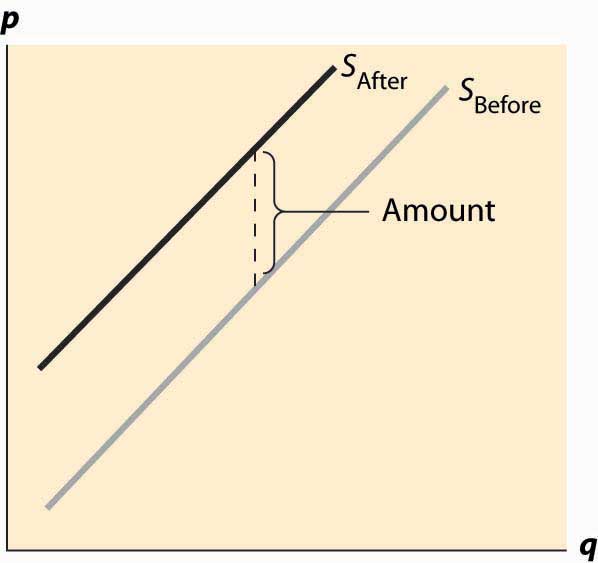

First, consider a tax imposed on the seller. At a given price p, and tax t, each seller obtains p – t, and thus supplies the amount associated with this net price. Taking the before-tax supply to be SBefore, the after-tax supply is shifted up by the amount of the tax. This is the amount that covers the marginal value of the last unit, plus providing for the tax. Another way of saying this is that, at any lower price, the sellers would reduce the number of units offered. The change in supply is illustrated in Figure 5.1 "Effect of a tax on supply".

Figure 5.1 Effect of a tax on supply

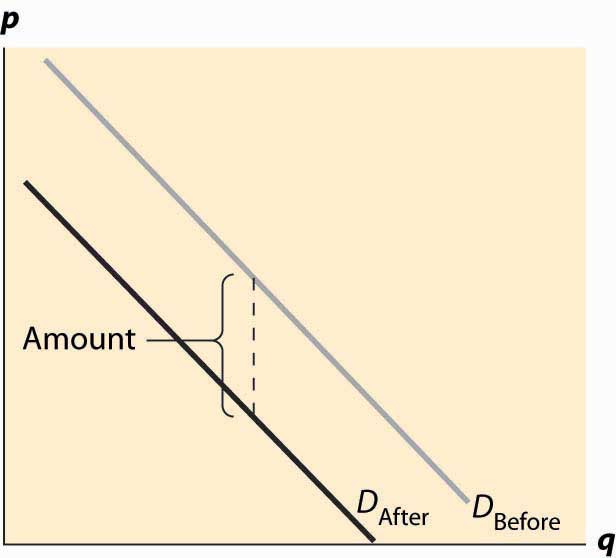

Now consider the imposition of a tax on the buyer, as illustrated in Figure 5.2 "Effect of a tax on demand". In this case, the buyer pays the price of the good, p, plus the tax, t. This reduces the willingness to pay for any given unit by the amount of the tax, thus shifting down the demand curve by the amount of the tax.

Figure 5.2 Effect of a tax on demand

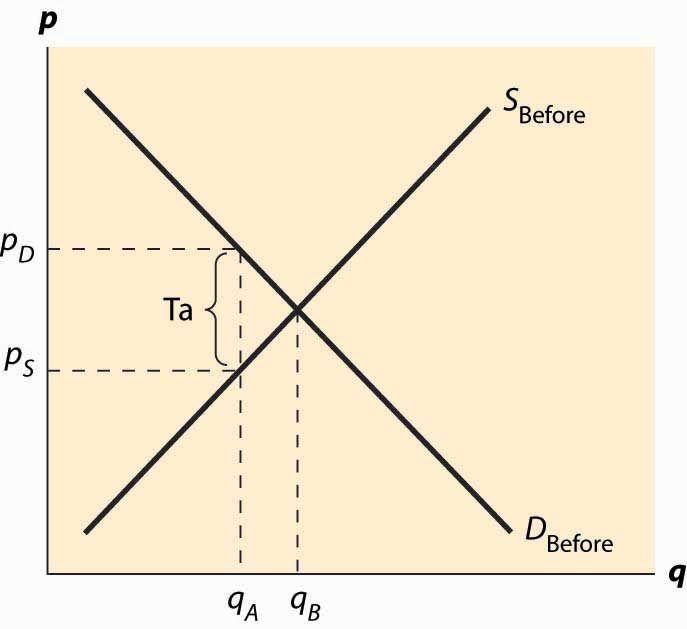

In both cases, the effect of the tax on the supply-demand equilibrium is to shift the quantity toward a point where the before-tax demand minus the before-tax supply is the amount of the tax. This is illustrated in Figure 5.3 "Effect of a tax on equilibrium". The quantity traded before a tax was imposed was qB*. When the tax is imposed, the price that the buyer pays must exceed the price that the seller receives, by the amount equal to the tax. This pins down a unique quantity, denoted by qA*. The price the buyer pays is denoted by pD* and the seller receives that amount minus the tax, which is noted as pS*. The relevant quantities and prices are illustrated in Figure 5.3 "Effect of a tax on equilibrium".

Figure 5.3 Effect of a tax on equilibrium

Also noteworthy in this figure is that the price the buyer pays rises, but generally by less than the tax. Similarly, the price that the seller obtains falls, but by less than the tax. These changes are known as the incidence of the taxChanges in the price paid for a good based on the amount of tax on the good.—a tax mostly borne by buyers, in the form of higher prices, or by sellers, in the form of lower prices net of taxation.

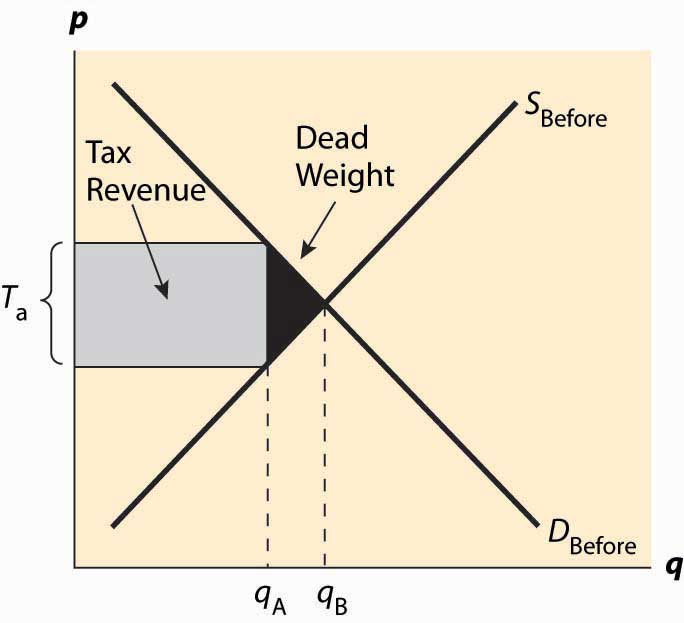

There are two main effects of a tax: a fall in the quantity traded and a diversion of revenue to the government. These are illustrated in Figure 5.4 "Revenue and deadweight loss". First, the revenue is just the amount of the tax times the quantity traded, which is the area of the shaded rectangle. The tax raised, of course, uses the after-tax quantity qA* because this is the quantity traded once the tax is imposed.

Figure 5.4 Revenue and deadweight loss

In addition, a tax reduces the quantity traded, thereby reducing some of the gains from trade. Consumer surplus falls because the price to the buyer rises, and producer surplus (profit) falls because the price to the seller falls. Some of those losses are captured in the form of the tax, but there is a loss captured by no party—the value of the units that would have been exchanged were there no tax. The value of those units is given by the demand, and the marginal cost of the units is given by the supply. The difference, shaded in black in the figure, is the lost gains from trade of units that aren’t traded because of the tax. These lost gains from trade are known as a deadweight lossThe buyer’s values minus the seller’s costs of units that are not economic to trade because of a tax or other interference in the market.. That is, the deadweight loss is the buyer’s values minus the seller’s costs of units that are not economic to trade only because of a tax or other interference in the market. The net lost gains from trade (measured in dollars) of these lost units are illustrated by the black triangular region in the figure.

The deadweight loss is important because it represents a loss to society much the same as if resources were simply thrown away or lost. The deadweight loss is value that people don’t enjoy, and in this sense can be viewed as an opportunity cost of taxation; that is, to collect taxes, we have to take money away from people, but obtaining a dollar in tax revenue actually costs society more than a dollar. The costs of raising tax revenues include the money raised (which the taxpayers lose), the direct costs of collection, like tax collectors and government agencies to administer tax collection, and the deadweight loss—the lost value created by the incentive effects of taxes, which reduce the gains for trade. The deadweight loss is part of the overhead of collecting taxes. An interesting issue, to be considered in the subsequent section, is the selection of activities and goods to tax in order to minimize the deadweight loss of taxation.

Without more quantification, only a little more can be said about the effect of taxation. First, a small tax raises revenue approximately equal to the tax level times the quantity, or tq. Second, the drop in quantity is also approximately proportional to the size of the tax. Third, this means the size of the deadweight loss is approximately proportional to the tax squared. Thus, small taxes have an almost zero deadweight loss per dollar of revenue raised, and the overhead of taxation, as a percentage of the taxes raised, grows when the tax level is increased. Consequently, the cost of taxation tends to rise in the tax level.

Key Takeaways

- Imposing a tax on the supplier or the buyer has the same effect on prices and quantity.

- The effect of the tax on the supply-demand equilibrium is to shift the quantity toward a point where the before-tax demand minus the before-tax supply is the amount of the tax.

- A tax increases the price a buyer pays by less than the tax. Similarly, the price the seller obtains falls, but by less than the tax. The relative effect on buyers and sellers is known as the incidence of the tax.

- There are two main economic effects of a tax: a fall in the quantity traded and a diversion of revenue to the government.

- A tax causes consumer surplus and producer surplus (profit) to fall.. Some of those losses are captured in the tax, but there is a loss captured by no party—the value of the units that would have been exchanged were there no tax. These lost gains from trade are known as a deadweight loss.

- The deadweight loss is the buyer’s values minus the seller’s costs of units that are not economic to trade only because of a tax (or other interference in the market efficiency).

- The deadweight loss is important because it represents a loss to society much the same as if resources were simply thrown away or lost.

- Small taxes have an almost zero deadweight loss per dollar of revenue raised, and the overhead of taxation, as a percentage of the taxes raised, grows when the tax level is increased.

Exercises

- Suppose demand is given by qd(p) = 1 – p and supply qs(p) = p, with prices in dollars. If sellers pay a 10-cent tax, what is the after-tax supply? Compute the before-tax equilibrium price and quantity, the after-tax equilibrium quantity, and buyer’s price and seller’s price.

- Suppose demand is given by qd(p) = 1 – p and supply qs(p) = p, with prices in dollars. If buyers pay a 10-cent tax, what is the after-tax demand? Do the same computations as the previous exercise, and show that the outcomes are the same.

- Suppose demand is given by qd(p) = 1 – p and supply qs(p) = p, with prices in dollars. Suppose a tax of t cents is imposed, t ≤1. What is the equilibrium quantity traded as a function of t? What is the revenue raised by the government, and for what level of taxation is it highest?