This is “Title from Nonowners”, section 18.2 from the book Basics of Product Liability, Sales, and Contracts (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

18.2 Title from Nonowners

Learning Objective

- Understand when and why a nonowner can nevertheless pass title on to a purchaser.

The Problem of Title from Nonowners

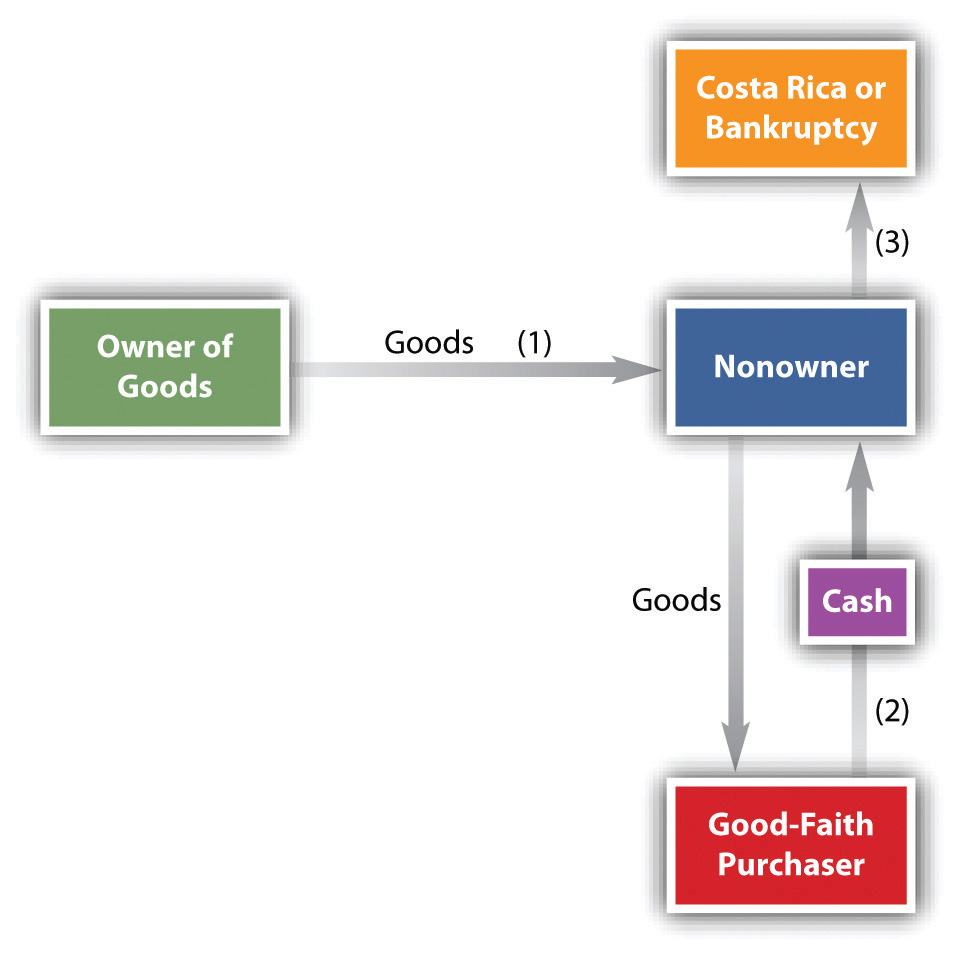

We have examined when title transfers from buyer to seller, and here the assumption is, of course, that seller had good title in the first place. But what title does a purchaser acquire when the seller has no title or has at best only a voidable title? This question has often been difficult for courts to resolve. It typically involves a type of eternal triangle with a three-step sequence of events, as follows (see Figure 18.1 "Sales by Nonowners"): (1) The nonowner obtains possession, for example, by loan or theft; (2) the nonowner sells the goods to an innocent purchaser for cash; and (3) the nonowner then takes the money and disappears, goes into bankruptcy, or ends up in jail. The result is that two innocent parties battle over the goods, the owner usually claiming that the purchaser is guilty of conversionThe civil wrong of taking property without its owner’s consent. (i.e., the unlawful assumption of ownership of property belonging to another) and claiming damages or the right to recover the goods.

Figure 18.1 Sales by Nonowners

The Response to the Problem of Title from Nonowners

The Basic Rule

To resolve this dilemma, we begin with a basic policy of jurisprudence: a person cannot transfer better title than he or she had. (The Uniform Commercial Code [UCC] notes this policy in Sections 2-403, 2A-304, and 2A-305.) This policy would apply in a sale-of-goods case in which the nonowner had a void title or no title at all. For example, if a nonowner stole the goods from the owner and then sold them to an innocent purchaser, the owner would be entitled to the goods or to damages. Because the thief had no title, he had no title to transfer to the purchaser. A person cannot get good title to goods from a thief, nor does a person have to retain physical possession of her goods at all times to retain their ownership—people are expected to leave their cars with a mechanic for repair or to leave their clothing with a dry cleaner.

If thieves could pass on good title to stolen goods, there would be a hugely increased traffic in stolen property; that would be unacceptable. In such a case, the owner can get her property back from whomever the thief sold it to in an action called replevinAn action to recover possession of goods wrongfully held. (an action to recover personal property unlawfully taken). On the other hand, when a buyer in good faith buys goods from an apparently reputable seller, she reasonably expects to get good title, and that expectation cannot be dashed with impunity without faith in the market being undermined. Therefore, as between two innocent parties, sometimes the original owner does lose, on the theory that (1) that person is better able to avoid the problem than the downstream buyer, who had absolutely no control over the situation, and (2) faith in commercial transactions would be undermined by allowing original owners to claw back their property under all circumstances.

So the basic legal policy that a person cannot pass on better title than he had is subject to a number of exceptions. In Chapter 22 "Secured Transactions and Suretyship", for instance, we examine how a buyer in the ordinary course of business is allowed to purchase goods free of security interests that the seller has given to creditors. Likewise, the law governing the sale of goods contains exceptions to the basic legal policy. These usually fall within one of two categories: sellers with voidable title and entrustment.

The Exceptions

As noted, there are exceptions to the law governing the sale of goods.

Sellers with a Voidable Title

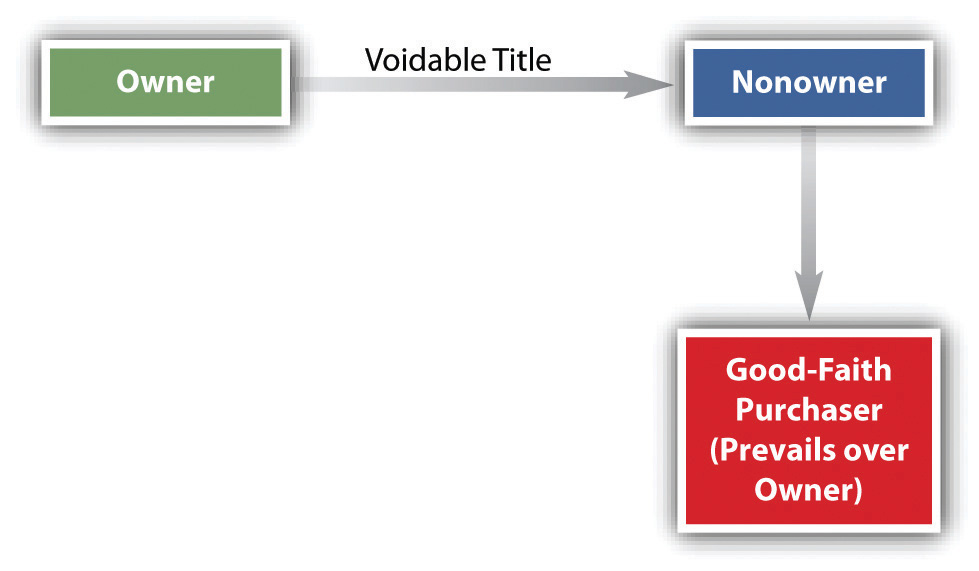

Under the UCC, a person with a voidable title has the power to transfer title to a good-faith purchaser for value (see Figure 18.2 "Voidable Title"). The UCC defines good faith as “honesty in fact in the conduct or transaction concerned.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 1-201(19). A “purchaser” is not restricted to one who pays cash; any taking that creates an interest in property, whether by mortgage, pledge, lien, or even gift, is a purchase for purposes of the UCC. And “value” is not limited to cash or goods; a person gives value if he gives any consideration sufficient to support a simple contract, including a binding commitment to extend credit and security for a preexisting claim. Recall from Chapter 9 "The Agreement" that a “voidable” title is one that, for policy reasons, the courts will cancel on application of one who is aggrieved. These reasons include fraud, undue influence, mistake, and lack of capacity to contract. When a person has a voidable title, title can be taken away from her, but if it is not, she can transfer better title than she has to a good-faith purchaser for value. (See Section 18.4.2 "Defrauding Buyer Sells to Good-Faith Purchaser for Value" at the end of this chapter.)

Rita, sixteen years old, sells a video game to her neighbor Annie, who plans to give the game to her nephew. Since Rita is a minor, she could rescind the contract; that is, the title that Annie gets is voidable: it is subject to be avoided by Rita’s rescission. But Rita does not rescind. Then Annie discovers that her nephew already has that video game, so she sells it instead to an office colleague, Donald. He has had no notice that Annie bought the game from a minor and has only a voidable title. He pays cash. Should Rita—the minor—subsequently decide she wants the game back, it would be too late: Annie has transferred good title to Donald even though Annie’s title was voidable.

Figure 18.2 Voidable Title

Suppose Rita was an adult and Annie paid her with a check that later bounced, but Annie sold the game to Donald before the check bounced. Does Donald still have good title? The UCC says he does, and it identifies three other situations in which the good-faith purchaser is protected: (1) when the original transferor was deceived about the identity of the purchaser to whom he sold the goods, who then transfers to a good-faith purchaser; (2) when the original transferor was supposed to but did not receive cash from the intermediate purchaser; and (3) when “the delivery was procured through fraud punishable as larcenous under the criminal law.”Uniform Commercial Code, Sections 2-403(1), 2-403(1), 2A-304, and 2A-305.

This last situation may be illustrated as follows: Dimension LLC leased a Volkswagen to DK Inc. The agreement specified that DK could use the Volkswagen solely for business and commercial purposes and could not sell it. Six months later, the owner of DK, Darrell Kempf, representing that the Volkswagen was part of DK’s used-car inventory, sold it to Edward Seabold. Kempf embezzled the proceeds from the sale of the car and disappeared. When DK defaulted on its payments for the Volkswagen, Dimension attempted to repossess it. Dimension discovered that Kempf had executed a release of interest on the car’s title by forging the signature of Dimension’s manager. The Washington Court of Appeals, applying the UCC, held that Mr. Seabold should keep the car. The car was not stolen from Dimension; instead, by leasing the vehicle to DK, Dimension transferred possession of the car to DK voluntarily, and because Seabold was a good-faith purchaser, he won.Dimension Funding, L.L.C. v. D.K. Associates, Inc., 191 P.3d 923 (Wash. App. 2008).

Entrustment

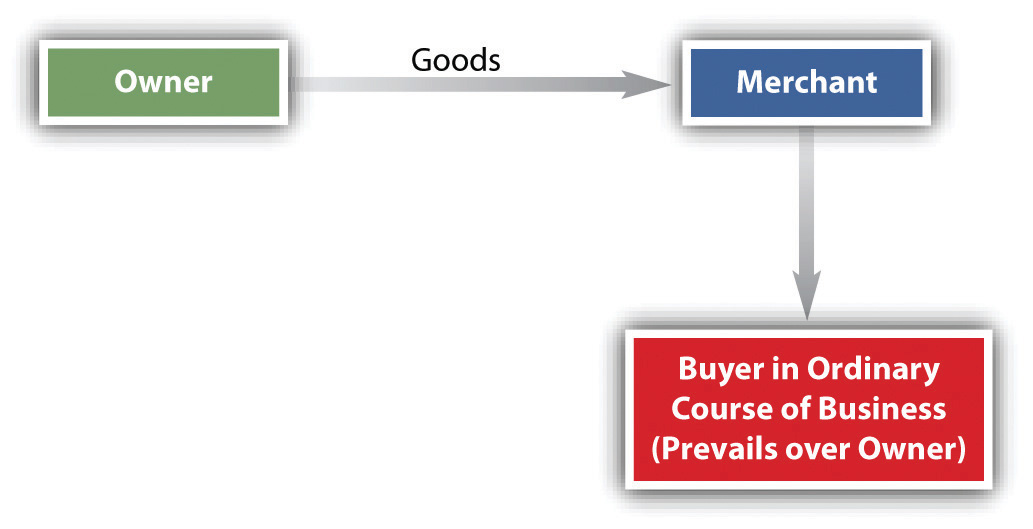

A merchant who deals in particular goods has the power to transfer all rights of one who entrusts to him goods of the kind to a “buyer in the ordinary course of business” (see Figure 18.3 "Entrustment").Uniform Commercial Code, Sections 2-403(2), 2A-304(2), and 2A-305(2). The UCC defines such a buyer as a person who buys goods in an ordinary transaction from a person in the business of selling that type of goods, as long as the buyer purchases in “good faith and without knowledge that the sale to him is in violation of the ownership rights or security interest of a third party in the goods.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 1-201(9). Bess takes a pearl necklace, a family heirloom, to Wellborn’s Jewelers for cleaning; as the entrustorOne who puts something into another’s possession for its care., she has entrusted the necklace to an entrusteeOne to whom something is put for its care.. The owner of Wellborn’s—perhaps by mistake—sells it to Clara, a buyer, in the ordinary course of business. Bess cannot take the necklace back from Clara, although she has a cause of action against Wellborn’s for conversion. As between the two innocent parties, Bess and Clara (owner and purchaser), the latter prevails. Notice that the UCC only says that the entrustee can pass whatever title the entrustor had to a good-faith purchaser, not necessarily good title. If Bess’s cleaning woman borrowed the necklace, soiled it, and took it to Wellborn’s, which then sold it to Clara, Bess could get it back because the cleaning woman had no title to transfer to the entrustee, Wellborn’s.

Figure 18.3 Entrustment

Entrustment is based on the general principle of estoppel: “A rightful owner may be estopped by his own acts from asserting his title. If he has invested another with the usual evidence of title, or an apparent authority to dispose of it, he will not be allowed to make claim against an innocent purchaser dealing on the faith of such apparent ownership.”Zendman v. Harry Winston, Inc., 111 N.E. 2d 871 (N.Y. 1953).

Key Takeaway

The general rule—for obvious reasons—is that nobody can pass on better title to goods than he or she has: a thief cannot pass on good title to stolen goods to anybody. But in balancing that policy against the reasonable expectations of good-faith buyers that they will get title, the UCC has made some exceptions. A person with voidable title can pass on good title to a good-faith purchaser, and a merchant who has been entrusted with goods can pass on title of the entrustor to a good-faith purchaser.

Exercises

- Why is it the universal rule that good title to goods cannot be had from a thief?

- What is the “voidable title” exception to the universal rule? Why is the exception made?

- What is the “entrusting” exception to the general rule?