This is “Groups and Meetings”, chapter 12 from the book An Introduction to Group Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 12 Groups and Meetings

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Introductory Exercise

The OOCSIP (On-And-Off-Campus Student Involvement Project)

Rationale:

Educational, social, and recreational events take place on college campuses all the time. You’ve probably seen information about these activities and been invited to them. But have you ever attended a campus committee meeting or a community meeting whose members include college employees? Probably not. Thus, you may not understand how a college and its community function. This project will help you acquire such understanding.

What Students Should Gain:

- Contact with knowledgeable college professionals whose ideas and actions affect students.

- Appreciations for the nature and aims of campus and community groups.

- Knowledge about group dynamics—including formal processes.

- A chance to expose college employees to students’ circumstances and perspectives.

Steps Students Should Take:

- Identify an Employee Contact at their college or university who’s willing to meet them at or take them to two on- or off-campus events.

- Attend two (2) on- or off-campus events with their Employee Contact.

- Complete an Assessment of a Student’s Campus/Community Participation Form [Note 12.47], including the front page signed by the Employee Contact.

- Complete a typed Critique of Formal Campus or Community Gathering Form [Note 12.48].

- Send a hand-written thank-you note to their Employee Contact.

Once I ran across something in a book that really agitated me. The volume presented lists of ideas for living a happy and fulfilled life. One of the lists was headed “Five Great Ways to Find a Friend.” Its first four ideas were to find a cause, find a church, find a class, and find a club. All those ideas seemed reasonable to me. Recommendation #5, however, was “find a committee.” When I saw this, I immediately asked myself, “What were the authors of this book eating, drinking, or smoking when they wrote this? Who with more sense than a pencil eraser would suggest actually LOOKING FOR A COMMITTEE TO JOIN for any reason whatsoever?”

Phil Venditti

Are you lonely?

Getting Started

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

A college administrator we know overheard her seven-year-old daughter and another little girl talking about their parents. “What does your mother do?” asked the other child. “She goes to meetings,” replied the administrator’s child.

Whether in educational settings or business or elsewhere, meetings dominate the way many groups operate in American society. Estimates of the number of meetings that take place every day in our country range from 11 million to more than 30 millionhttp://www.studergroup.com/dotCMS/knowledgeAssetDetail?inode=269049. One authority claims that the average chief executive officer spends 17 hours per week in meetings, whereas the average senior executive spends 23 hours per week.Amos, J. (2002). Making meetings work (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Howtobooks.

If the average number of people in each of these meetings is only five and the average meeting lasts only one hour, this means that between 55,000,000 and 150,000,000 person-hours each day are being consumed by meetings. Assuming a 50-week work year, then, the total time devoted to meetings each year amounts to at least fifteen billion person-hours. As for you, yourself, one estimate is that you’ll spend 35–50% of every workweek in meetings, for a total of more than 9,000 hours over the course of your lifetime.Doyle, M., & Straus, D. (1993). How to make meetings work: The new interaction method. New York: Jove Books.

If meetings are so central to what groups do, and so time-consuming, it makes sense to pay attention to how they’re conducted. Like any other course of action, the process of engaging in meetings has a beginning, a middle, and an end. In our first section we’ll consider the beginning—the planning part. Later we’ll look at techniques for facilitating a meeting, the use of Robert’s Rules of Order, and the best ways to follow up after a meeting.

12.1 Planning a Meeting

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify questions whose answers can determine whether a meeting should be held.

- List obligations that group members should accept when they attend meetings.

- Discuss guidelines for planning an effective meeting.

Aller Anfang ist schwer.

German saying (“All beginnings are difficult.”)

The beginning is half the job.

Korean saying

“Meetings should be viewed skeptically from the outset, as risks to productivity.”http://www.codinghorror.com/blog/2012/02/meetings-where-work-goes-to-die.html

Jeff Atwood

Whether and how carefully you plan any undertaking will determine in large part how well it turns out. Bad planning makes it harder to achieve your goals; good planning makes it easier. This certainly applies to meetings of groups, so it’s wise for us to examine how to plan those meetings effectively. Before we consider the ins and outs of that planning, however, let’s reflect on the proper role of meetings.

What Are Meetings for?

Office equipment and supplies constitute tools to support the work of most modern groups such as student teams in college classes, employees and executives in businesses, and collections of people in other organizations. None of those groups would say, however, that using copy machines and staplers is one of their goals. And none of them would visit a copy machine unless they had something they needed to reproduce. They wouldn’t grab a stapler, either, unless they had some papers to attach to each other.

Meetings resemble office supplies in at least one way: they can help a group accomplish its goals. But meetings are like office supplies in another way, too: they’re only a means toward reaching group goals, not an end in themselves. And sometimes they’re even antithetical to the efficient functioning of a group. One statistical analysis of workers’ reactions to meetings discovered a significant positive relationship between the number of meetings attended and both the level of fatigue and the sensation of being subjected to a heavy work load.Luong, A., & Rogelberg, S.G. (2005). Meetings and more meetings: The relationship between meeting load and the daily well-being of employees. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9(1), 58–67.

Remember these truths, therefore: If it is operating well, your group at some point probably adopted goals for itself. It may even have ranked those goals in order of importance. Members of a student team might, for example, decide that their joint goals are to earn a high grade on their group project, to have fun together, and to ensure that all of them can secure a positive recommendation from the instructor when they look for a job after graduation.

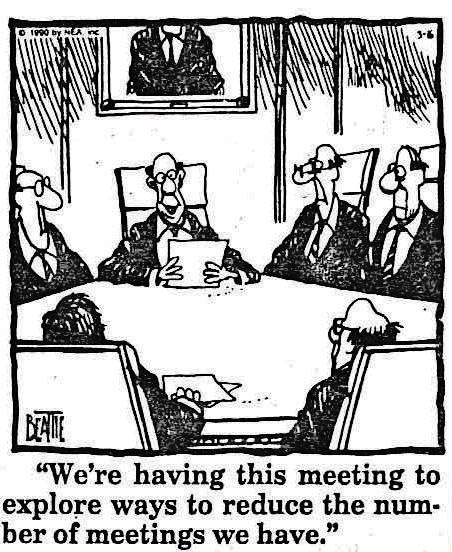

“To meet” is not one of the goals of any group, though, is it? No; your goals involve doing things, not meeting—not even meeting to decide what you’re going to do and whether you’re doing it. Therefore, you should not meet until and unless doing so will clearly contribute to a real goal of your group.

What this means in practical reality is that many, many regularly-scheduled meetings probably ought to be canceled, postponed, or at the very least substantially shortened. It means that meetings which aren’t part of an official, ongoing series should be conducted only if the people who would be participating agree that having the meetings is necessary to answer a question, solve a problem, make a decision, or ensure that people know what it is they are and should be doing. It means, in short, that a group’s “default position” should be never to meet.

If you’re in a position to decide whether and when a meeting will take place, you’re in control of what some might consider other people’s most valuable possession: their time. If you take this responsibility seriously and act on it wisely, your fellow group members will appreciate it—especially since many group leaders don’t do so.

To Meet or Not to Meet

In the twenty-first century, technology offers techniques for accomplishing many group goals without meeting face to face. A helpful website called “Lifehacker”http://www.lifehack.org/articles/productivity/kill-meetings-to-get-more-done.html suggests that you follow these steps before scheduling in-person meetings:

Get done what you can by email. If email doesn’t accomplish your aims, use the telephone. Only if neither email nor the phone works should you meet face to face.

Calculate the opportunity costThe loss of potential gain from other alternatives when any one option is selected. of a potential meeting. What task(s) that you could be engaged in at the time of the meeting will you have to postpone, or forgo entirely, because of the meeting? Is it worth it?

Ask yourself what bad results, if any, will come to pass if you don’t meet. What about if you don’t meet this time, but later instead? If the bad things which you expect to arise if you don’t meet are minimal or can be dealt with easily, don’t meet, or at least not now.

Ask if it’s essential for everyone in the group to be at the same physical location at the time of the meeting. Assess whether the chore of just moving people’s molecules from one place to another could render a face-to-face meeting undesirable.

If It’s “to Meet,” Then What?

Once you’ve decided that you should hold a meeting of some sort, you should do your best to make sure it will run well. Part of this undertaking is to ensure that all the members of your group understand the significance of the time they’ll be devoting to getting together. To this end, you may want to create a list of basic obligations you feel everyone should fulfill with respect to all meetings. These obligations might include the following items:

- If you can’t make it to a meeting, let the person who’s organizing it know in a timely fashion. If you were expected to make a report or complete a task of some sort by the time of the meeting, either submit the report through someone else who will be there or inform the organizer of when you’ll finish what you’re committed to be doing. If you can find someone to fill in for you at the meeting, do it.

- If you can attend the meeting, prepare for it. Read meeting announcements and agendas. Take necessary and appropriate information and tools with you to each meeting. Come to meetings with an open mind and with a mental picture of what you may contribute to the discussion.

- Pay attention. Avoid side conversations or other actions that might keep you from understanding what’s going on in a meeting.

- Be clear and concise. Seek parsimonious discourse. Don’t speak unless you’re sure you’ll improve over silence by doing so.

- Wait to express your own opinion until you’re sure you understand others’ views.

- Challenge assumptions, but stick to the topic and offer constructive rather than destructive criticism.

- Know when to give in on a matter of disagreement. Stick to your convictions, but consider carefully whether you need to have your way in any particular situation.

Guidelines for Planning a Meeting

Again, first of all: don’t meet at all unless you need to. Once you’ve determined that a meeting will promote rather than hinder productivity, preparing for it well will give you a head start on maximizing its effectiveness. Here are six guidelines to take into account as you plan a meeting:

-

Identify the specific goals.

Identify the specific goals you plan to achieve in the meeting and the methods you’ll use to decide if you’ve achieved them. Write the goals down. Reread them. Let them sit a while. Read them again to see if they’re still appropriate and necessary.

If the goals of the meeting still look as though they’re all valuable, remember Dwight Eisenhower’s dictum that “What is important is seldom urgent, and what is urgent is seldom importanthttp://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newHTE_91.htm.” If you’re not sure you can get everything done that you hope to in the time you’ll have available, set priorities so that the most urgent items are taken care of quickly and you can postpone others without endangering what’s most important to get done.

-

Decide carefully who needs to attend.

At one point, Amazon Corporation implemented a “two-pizza guidelineA policy by Amazon Corporation to limit membership in its employee teams to the quantity which could be fed with two pizzas.” whereby it limited the number of people who composed its teams to the quantity that could be fed with two pizzashttp://www.fastcompany.com/50106/inside-mind-jeff-bezos. If you calculate that the people you plan to invite to your meeting constitute larger than a two-pizza group, ask yourself if all of them really, really, really need to be there.

-

Produce a clear, brief, thorough, informative agenda.

Don’t spring surprises on people. To give them a solid idea of what to expect, divide the meeting’s agendaA specific written plan describing the purpose and contents of a meeting. into simple categories: for instance, establishment of a quorum; approval of minutes and the agenda; officers’ and (sub)committee reports; unfinished business; new business, and “other.” For each item, name the individual in charge of it, indicate whether it will require action by the group, and provide an estimated duration. (You’ll need to confirm these estimates with the responsible parties, of course). If you expect some or all of the group’s members to complete a task before they arrive, such as reading a report or generating possible solutions to a problem, tell them so clearly.

Here’s a special note, too: Don’t plan to stretch the contents of a meeting to fit a preordained time. Strive to cut down on how long you spend to handle each item on your agenda as much as you can so that members of your group can get back to their other responsibilities as soon as possible. A shorter-than-expected meeting is usually a thing of joy.

-

Pick a good venue.

If you have a choice, plan to gather in a place with plenty of light, comfortable furniture, and a minimum of distracting sounds or sights. You should be able to adjust the temperature, too, if people get too hot or cold. Make sure that any technological tools you think will be available to you are actually going to be on hand when you meet and that they’re all functioning. Even if you expect to have access to a laptop computer and a projector, plan to bring a flip chart and markers so that people will be able to express and record ideas spontaneously during the meeting. And all other things being equal, find a place to meet regularly which is large enough and secure enough to allow your group members to store the “tools of their trade” there—flipcharts, writing supplies, reference books, etc.—between gatherings.

-

Make sure the participants receive the agenda.

Make sure people receive the agenda you’ve prepared in a timely fashion so they’ll know why, when, where, and for how long the group is expected to meet. Two reminders per meeting may be enough—one by letter and one by e-mail, for instance—but three are better, including one the day before the meeting itself. Free computer-based confidential text-messaging services such as Class Parrot (http://classparrot.com/) and kikutext (https://kikutext.com/) can provide another channel for reaching group members.

One college president from a Southern state maintained that he’d gotten his board of trustees to act “like trained seals,” partly through thorough preparation for their meetings. In fact, the president actually ran practice meetings with the board to make sure there would be no surprises when the real meetings took place. You should practice, too, at gently, repeatedly, and clearly notifying other group members of the time and agenda of each meeting. For every person who thinks you’re being repetitive, two or three will thank you for keeping them from overlooking the meeting.

If you’re planning to meet in a place for the first time, or if you’re expecting someone to attend your meeting for the first time, be sure to provide clear and complete directions to the location. With online tools such as mapquest.com and google maps at your disposal, it should cost you very little time to locate such directions and send them to members of your group.

-

Arrive early.

Arrive early to size up and set up the place where you’re meeting. Rooms sometimes get double-booked, furniture sometimes gets rearranged, technological tools such as LCD projectors and laptop computers sometimes break down or get taken away to be repaired, and so on and on. If you’re the person in charge of leading the meeting, you need to know first if unexpected happenings like these have taken place.

Following these half-dozen guidelines won’t guarantee that your meetings will be as successful as you wish them to be. If you don’t heed them, however, you’re apt to encounter considerable difficulty in achieving that aim.

Key Takeaway

- Meetings should be avoided unless they are clearly necessary, but preparing for them well can enable a group to advance its objectives.

Exercises

- Identify a group of which you’re a member. What percentage of its meetings in the past year do you feel contributed significantly to its stated objectives? What role did pre-meeting planning play in producing that outcome?

- Think about a time when a group you were part of canceled or postponed a meeting. On what grounds did it reach that decision? Why do you approve or disapprove of the decision?

- What do you consider to be the pros and cons of limiting the number of people invited to a group meeting?

- Describe for a classmate your ideal venue for a group meeting. What equipment, amenities, and other provisions do you feel would best assist a group to achieve the aims of its meetings?

12.2 Facilitating a Meeting

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Describe features of a poorly-facilitated group meeting

- Identify guidelines for facilitating a meeting effectively.

- Discuss steps for facilitating virtual meetings.

Most committees I’ve served on have been inefficient, superfluous, repetitive, sluggish, unproductive, erratic, rancorous, or boring—or all of the above. By and large, they’ve wasted my time and the time of many other people.

Frequently, everyone in the group eagerly helped identify jobs that needed to be accomplished, but just a few members ended up shouldering the burdens and completing the tasks. The rest did their best to avoid the group entirely and had to be cajoled or badgered to take part in meetings and work. Most of the meetings oscillated between tedium, dreariness, and fruitless conflict. In short, the meetings were cesspools of futility.

Phil Venditti

Preparing for group meetings well takes you a third of the way toward ensuring their productivity, and follow-up takes care of another third. The middle third of the process is to run the meetings efficiently.

Make no mistake: facilitating a meeting well is difficult. It requires care, vigilance, flexibility, resilience, humility, and humor. In a way, in fact, to run a meeting effectively calls upon you to act the way a skilled athletic coach does, watching the action, calling plays, and encouraging good performance. Furthermore, you need to monitor the interaction of everyone around you and “call the plays” based on a game plan that you and your fellow group members have presumably agreed upon in advance. Finally, like a coach, you sometimes need to call timeouts—breaks—when people are weary or the action is starting to get raggedy or undisciplined.

A Meeting Heroine

We will list and explain several principles and practices of good meeting facilitation in this section, but first let’s consider a friend and colleague of ours named Bonnie. Bonnie is the best meeting facilitator we’ve ever met, for several reasons. First of all, she makes it a point to become familiar with not only the issues and topics to be dealt with in a meeting, but also the personalities, strengths, and foibles of the other people who will be participating. Although she behaves in a warm and friendly manner at all times during a meeting, she never veers off into extraneous or superfluous details just for the sake of being sociable.

Because she attends closely to every interaction in a meeting and takes the time in advance to become familiar with the styles and proclivities of participants, Bonnie prevents discussions from getting off track. In fact, she has an uncanny knack of being able to spot a train of discussion that might even just be getting ready to go off track so that she can nudge it safely around bends and down slippery slopes. Furthermore, she seems to always know exactly what questions to ask, and to whom, to elicit concise, purposeful information which helps the group keep moving in the proper direction.

Bonnie is totally efficient and systematic in her pacing and wastes no time from the moment a meeting begins to the moment it ends…or afterward, either. If you go to a meeting led by Bonnie and its purpose is to plan an event—an Arbor Day celebration, for example, since that’s a project she oversees every year in the town where she lives—you can be confident of the outcome. When the meeting ends, the event will be planned and you will be feeling good about yourself, about the meeting itself, and about the future of the group.

Perils of Poor Facilitation

Unfortunately, many people lack the skills of our friend Bonnie. As a result, a variety of negative results can take place as they fail to act capably as meeting facilitators. Here are some signs that there’s “Trouble in River CityA term from the musical “The Music Man” referring to problems lurking ahead of an unsuspecting group or community.” in a meeting:

- An argument starts about an established fact.

- Opinions are introduced as if they were truths.

- People intimidate others with real or imaginary “knowledge.”

- People overwhelm each other with too many proposals for the time available to consider them.

- People become angry for no good reason.

- People promote their own visions at the expense of everyone else’s.

- People demand or offer much more information than is needed.

- Discussion becomes circular; people repeat themselves without making any progress toward conclusions.

If you’ve experienced any of these symptoms of a poorly-facilitated meeting, you realize how demoralizing they can be for a group.

Guidelines for Facilitating a Meeting

Barge (1991)Barge, J.K. (1991, November). Task skills and competence in group leadership. Paper presented at the meeting of the Speech Communication Association, Atlanta, GA., Lumsden and Lumsden (2004)Lumsden, G., & Lumsden, D. (2004). Communicating in groups and teams: Sharing leadership (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning., and Parker and Hoffman (2006)Parker, G., & Hoffman, R. (2006). Meeting excellence: 33 tools to lead meetings that get results. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. are among many authorities who have recommended actions and attitudes which can help you facilitate a meeting well. Here are several such suggestions, taken partly from these writers’ works and partly from the authors’ experiences as facilitators and participants in meetings over the years:

-

Start promptly…always.

Some time, calculate the cost to your group—even at minimum-wage rates—for the minutes its members sit around waiting for meetings to begin. You may occasionally be delayed for good reasons, but if you’re chronically late you’ll eventually aggravate folks who’ve arrived on time—the very ones whose professionalism you’d particularly like to reinforce and praise. Consistently starting on time may even boost morale: “Early in, early out” will probably appeal to most of a group’s members, since they are likely to have other things they need to do as soon as a meeting ends.

-

Begin with something positive.

Face it: no matter what you do, many people in your group would probably rather be somewhere else than in a meeting. If you’d like them to overcome this familiar aversion and get pumped up about what you’ll be doing in a meeting, therefore, you might emulate the practice of City Year, a Boston-based nonprofit international service organization. City Year begins its meetings by inviting members to describe from their own recent life experiences an example of what Robert F. Kennedy referred to as a “ripple of hope.”Grossman, J. (1998, April). We’ve got to start meeting like this. Inc., 70–74.This could be a good deed they’ve seen someone do for someone else, a news item about a decline in the crime rate, or perhaps even a loving note they’ve received from a child or other family member. Sharing with their fellow group members such examples of altruism, love, or community improvement focuses and motivates City Year members by reminding them in specific, personal terms of why their meetings can be truly worthwhile.

-

Tend to housekeeping details.

People’s productivity depends in part on their biological state. Once you convene your meeting, announce or remind the group members of where they can find rest rooms, water fountains, vending machines, designated smoking areas, and any other amenities that may contribute to their physical comfort.

-

Make sure people understand their roles.

At the start of the meeting, review what you understand is going to happen and ask for confirmation of what you think people are expected to do in the time you’re going to be spending together. Calling on someone to make a report if he or she isn’t aware it’s required can be embarrassing for both you and that person.

-

Keep to your agenda.

Social time makes people happy and relieves stress. Most group meetings, however, should not consist primarily of social time. You may want to designate a “sheriffA group member designated to observe the dynamics of a meeting and steer people back on task when departures from its agenda take place.”—rotating the role at each meeting—to watch for departures from the agenda and courteously direct people back on task. Either you or the “sheriff” might want to periodically provide “signpostsNotifications of chronological stages in a meeting—e.g., “We have 25 minutes left, and we haven’t decided yet who will talk to the professor to ask about an extension on our assignment.”” indicating where you are in your process, too, such as “It looks like we’ve got 25 minutes left in our meeting, and we haven’t discussed yet who’s going to be working on the report to give to Mary.”

If your meetings habitually exceed the time you allot for them, consider either budgeting more time or, if you want to stick to your guns, setting a kitchen timer to ring when you’ve reached the point when you’ve said you’ll quit. The co-founder of one technology firm, Jeff Atwood, put together a list of rules for his company’s meetings which included this one: “No meeting should ever be more than an hour, under penalty of death.”Milian, M. (2012, June 11-June 17). It’s not you, it’s meetings. Bloomberg Businessweek, 51–52. Similarly, the library staff at one college in the Midwest conducts all their meetings standing up in a circle, which encourages brevity and efficiency.

-

Guide, don’t dictate.

If you’re in charge of the meeting, that doesn’t mean you’re responsible for everything people say in it, nor does it mean you have to personally comment on every idea or proposal that comes up. Let the other members of the group carry the content as long as they’re not straying from the process you feel needs to be followed.

You may see that some people regularly dominate discussion in your group’s meetings and that others are perhaps slower to talk despite having important contributions to make. One way to deal with these disparities is by providing the group with a “talking stick” and specifying that people must hold it in their hands in order to speak. You could also invoke the “NOSTUESOA technique to ensure that all members in a group participate in its discussions. rule” with respect to the talking stick, which says that “No One Speaks Twice Until Everybody Speaks Once.”

-

Keep your eyes open for nonverbal communication.

As a meeting progresses, people’s physical and emotional states are likely to change. As the facilitator, you should do your best to identify such change and accommodate it within the structures and processes your group has established for itself. When people do something as simple as crossing their arms in front of them, for instance, they might be signaling that they’re closed to what others are saying—or they might just be trying to stay warm in a room that feels too cold to them.

When one person in the meeting has the floor and is talking, it’s a good idea to watch how the rest of the group seems to be responding. You may notice clues indicating that people are pleased and receptive, or that they’re uninterested, skeptical, or even itching to respond negatively. You may want to do a perception checkA question or questions designed to determine if one’s interpretation of someone else’s behavior is accurate. to see if you’re interpreting nonverbal cues accurately. For instance, you might say, “Terry, could we pause here a bit? I get the impression that people might have some questions for you.” As an alternative, you might address the whole group and ask “Does anyone have questions for Terry at this point?”

-

Capture and assign action items.

Unless they are held purely to communicate information, or for other special purposes, most meetings result in action items, tasks, and other assignments for one or more participants. Sometimes these items arise unexpectedly because someone comes up with a great new idea and volunteers or is assigned to pursue it after the discussion ends. Be on the alert for these elements of a meeting.

-

Make things fun and healthy.

Appeal to people’s tummies and funnybones. Provide something to eat or drink, even if it’s just coffee or peanuts in a bowl. Glenn Parker and George Hoffman’s book on how to run meetings wellParker, G., & Hoffman, R. (2006). Meeting excellence: 33 tools to lead meetings that get results. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. includes a chapter titled “Eating Well=Meeting Well,” and it also refers to the fact that the American Cancer Society offers a program to help groups organize meetings and other events with good health in mind.http://www.cancer.org/healthy/morewaysacshelpsyoustaywell/meeting-well-description

-

Avoid sarcasm and cynicism.

Encourage humor and merriment. If your agenda includes some challenging items, try to start out with “quick winsSimple, noncontroversial questions which can be answered easily at the start of a meeting to offer its participants a sense of unity and direction.” to warm the mood of the group.

-

Take breaks regularly, even when you think you don’t need them.

If you’ve ever gone on a long hike on a beautiful day, you may have decided to continue a mile or two beyond your original intended destination because the scenery was beautiful and you were feeling spunky. If you’re like the authors, though, you probably regretted “going the extra mile” later because it meant you had to go back that mile plus all the rest of the way you’d come.

Something similar can arise in a meeting. People sometimes feel full of energy and clamor to keep a lively discussion going past the time scheduled for a break, but they may not realize that they’re tiring and losing focus until someone says or does something ill-advised. Taking even five-minute breathers at set intervals can help group members remain physically refreshed over the long haul.

-

Show respect for everyone.

Seek consensus. Avoid “groupthink” by encouraging a free and full airing of opinions. Observe the Golden Rule. Listen sincerely to everyone, but avoid giving a small minority so much clout that in disputed matters “99-to-1 is a tie.” Keep disagreements agreeable. If you must criticize, criticize positions, not people. If someone’s behavior shows a pattern of consistently irritating others or disrupting the flow of your group’s meetings, talk to the person privately and express your concern in a polite but clear fashion. Be specific in stating what you expect the person to do or stop doing, and keep an open mind to whatever response you receive.

-

Expect the unexpected.

Do your best to anticipate and prepare for confrontations and conflicts. If you didn’t already make time to do so earlier, take a minute just before the start of the meeting to mark items on your agenda which you think might turn out to be especially contentious or time-consuming.

-

Conduct multiple assessments of the meeting.

Formative assessmentJudgment concerning a process which is conducted before it is completed. takes place during an activity and allows people to modify their behavior in response to its results. Why not perform a brief interim evaluation during every meeting in which you ask, for instance, “If we were to end this meeting right now, where would it be, and if we need to make changes now in what’s happening in our meeting, what should they be?”

Summative assessmentJudgment concerning a process which has concluded. is implemented at the end of an activity. When you finish a meeting, for example, you might check to see how well people feel that the gathering met its intended goals. If you want something in writing, you might distribute a half sheet of paper to each person asking “What was best about our meeting?” and “What might have made this meeting better?” Or you could write two columns on a whiteboard, one with a plus and the other with a minus, and ask people orally to identify items they think belong in each category. If you feel a less formal check-up is sufficient, you might just go around the table or room and ask every person for one word that captures how she or he feels.

-

Think (and talk) ahead.

If you didn’t write it on your agenda—which would have been a good idea, most likely—remind group members, before the meeting breaks up, of where and when their next gathering is to take place.

Tips For Virtual Meetings

Meetings conducted via Skype or other synchronous technological tools can function as efficiently as face-to-face ones, but only if the distinctive challenges of the virtual environment are taken into account. It’s harder to develop empathy with other people, and easier to engage in unhelpful multitasking, when you’re not in the same physical space with them. To make it more likely that a virtual meeting will be both pleasant and productive, then, it makes sense to tell people up front what your expectations are of their behavior. If you want them to avoid reading email or playing computer solitaire on their computers while the meeting is underway, for example, say so.

A major goal of most meetings is to reach decisions based on maximum involvement, so it pays to keep in mind that people work best with other people whom they know and understand. With this in mind, you might choose to email a photo of each person scheduled to be in the meeting and include a quick biography for everyone to look over in advance. This communication could take place along with disseminating the meeting’s agenda and other supporting documentation.

Here are some further tips and suggestions for leading or participating in virtual meetings, each based on the unique features of such gatherings:

- Get all the participants in an audio meeting to say something brief at the start of the meeting so that everyone becomes familiar with everyone else’s voice.

- Remind people of the purpose of the meeting and of the key outcome(s) you hope to achieve together.

- Listen/watch for people who aren’t participating and ask them periodically if they have thoughts or suggestions to add to the discussion.

- Summarize the status of the meeting from time to time.

- If you’re holding an audio conference, discourage people from calling in on a cell phone because of potential problems with sound quality.

- Because you may not have nonverbal cues to refer to, ask other members to clarify their meanings and intentions if you’re not sure their words alone convey all you need to know.

- If you know you’re going to have to leave a meeting before it ends, inform the organizer in advance. Sign off publicly, but quickly, when you leave rather than just hanging up on the meeting connection.

Key Takeaway

- Facilitating a meeting well requires a large number of skills and talents and depends on overcoming many potential pitfalls, but following specific recommendations from authorities on the subject can make it possible.

Exercises

- Reread the description of Bonnie’s abilities. With a partner, list the abilities and rank them in what you feel is their order of importance. Which of the abilities, if any, do you feel are absolutely essential to successful leadership of meetings?

- Which instances of “Trouble in River City” have you experienced in group meetings? Describe two or three such instances. What action might the group leader have taken to prevent or resolve the episodes?

- Some cultures value exact punctuality differently from others. If you were leading a series of meetings comprising members of several cultural groups, what steps, if any, would you take to accommodate or modify people’s habits and expectations concerning the starting and ending times of the meetings?

- Imagine that you’re the new chairperson of a group which got seriously off track in the first of its meetings that you presided over. You tried gently redirecting people to discuss pertinent issues, but they first ignored and then resisted your attempts. What steps might you take to address the situation?

12.3 A Brief Introduction to Robert’s Rules of Order

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify ways in which parliamentary procedure can help a group conduct its business effectively.

- Distinguish between Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised (RONR) and related summaries of parliamentary procedure.

- Master terminology related to major actions undertaken within parliamentary procedure.

Manners are a sensitive awareness of the feelings of others. If you have that awareness, you have good manners, no matter what fork you use.

Emily Post

In the previous two sections, we considered a number of practical planning, human relations, and communication guidelines to help you get ready for a meeting and facilitate it. Now we’ll discuss a system of formal rules called “parliamentary procedureA system of rules for conducting the business of an organization in ways which ensure consistency, fairness, and efficiency.” which you may follow as you facilitate a meeting to save lots of time, prevent ill feelings, promote harmony, and ensure that everyone’s viewpoints can be expressed and discussed democratically.

Why Parliamentary Procedure?

It’s easy to make fun of individuals or groups who follow procedures “to the letter,” especially in a country like the United States where we at least say that we prize spontaneity and self-determination. When it comes to most groups you work in or lead as a student or employee, you’ll probably be able to get away with conducting their meetings fairly informally, or even “by the seat of your pants.” In such groups—“among friends,” as it were—parliamentary procedure may seem boring or unnecessary. You may just assume, for instance, that you’ll observe the will of the majority in cases of disagreement and that you’ll keep track of what you do by taking a few simple notes when you get together.

But what about when you’re asked to chair your children’s PTA some day? Or when you’re elected president of a community service group like Kiwanis or Rotary? Or when you become an officer in a professional society? Under those circumstances, you’ll have entered a “deliberative assemblyAny formal group which considers options and reaches decisions.”—a body that considers options and reaches decisions—and you’ll benefit from knowing at least the rudiments of parliamentary procedure in order to fulfill your duties within it. When you’re in charge of running such a group’s meetings, you should be able to ensure that things run smoothly, efficiently, and fairly. As odd as it sounds, under those circumstances you’ll probably actually find that imposing regulation on the group is necessary to preserve its freedom to act.

On a very practical level, parliamentary procedure can help you answer these common, important questions as you lead a meeting:

- Who gets to speak when, and for how long?

- What do we do if our discussion seems to be going on and on without any useful results?

- When and how do we make decisions?

- What do we do if we’re not ready yet to say yes or no to a proposal but need to move on to something else in the meantime?

- What do we do if we change our minds?

Learning some parliamentary procedure promises at least two personal benefits, as well. First, you’ll probably discover that the structures you become familiar with through using parliamentary procedure boost your confidence in general. Second, you’re apt to find that you’ve laid the foundations for establishing yourself as a solid, reliable leader. Third, although you shouldn’t be stricter or more formal than is good for your group, using parliamentary procedure regularly and as a matter of course should contribute to the impression that you care about consistency, equity, and efficiency in your dealings with other people in general.

Background of Robert’s Rules

Henry Martyn Robert was an engineer who rose to the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. Army and first put together his Rules of Order in 1876. His aim was to keep that publication to 50 pages, but its first edition contained 176 pages. The eleventh edition now runs nearly four times as long—more than 650 pages. This current edition, abbreviated as “RONR” (Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised), was formulated by a team of parliamentariansAn expert in parliamentary procedure. which includes Robert’s grandson.

A shorter summary, also prepared in part by Henry Martyn Robert III, comprises the most important features of RONR. It includes the contention that “at least 80 percent of the content of RONR will be needed less than 20 percent of the time” in even the largest, most complicated groups (Robert, Evans, Honemann, & Balch, 2011, p. 6Robert, H.M., Evans, W.J., Honemann, D.H., & Balch, T. J. (2011). Robert’s rules of order newly revised, in brief. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press.). Thus, a formal group which adopts RONR as its parliamentary authority may decide to use the summary volume to help it get through most common operational situations, since the summary’s sections are all linked item-by-item to more detailed portions of RONR itself.

Ingredients of RONR

Robert’s Rules offers guidance for all the essential processes a group is apt to conduct. It suggests that a group select a chairperson (“chairman” in Robert’s original language) and a secretary, that it decide on what proportion of its membership constitutes a quorumThe portion of a group’s membership required for it do conduct substantive activities such as voting on motions. and is thus able to conduct substantive business, and that it follow at least a “simplified standard order of businessThe major segments of a group’s business at a meeting, according to Robert’s Rules of Order.” which may be as straightforward as this:

- Reading and approval of minutes. Deciding whether notes of the previous meeting, generally taken by the group’s secretary, can be accepted as written or need to be modified.

- Reports. Statements by officers and heads of committees, along with any recommendations associated with them. For instance, the finance committee of a student government association might propose that the association as a whole spend money from a particular budget to send a student representative to a professional conference or purchase new bookkeeping software for the association’s treasurer.

- Unfinished business. Some groups use the term “old business” in this part of their agendas and allow members to bring up any topics that have occupied the body’s attention throughout its history, but RONR discourages this. Instead, it insists that “unfinished business” be restricted to items which were left incomplete at the conclusion of the previous meeting or which were scheduled to be considered in the previous meeting but could not be because of insufficient time and were therefore specifically postponed to the next one.Robert, H.M., Evans, W.J., Honemann, D.H., & Balch, T. J. (2011).

- New business. This part of a meeting revolves around motions introduced by members and considered by the group as a whole.

Agendas

Although a bare-bones standard order of business may satisfy the requirements of RONR, most groups decide to make use of an agenda such as the ones we’ve discussed in earlier sections of this chapter. Such agendas, if and when they are approved by groups at the outset of their meetings, may be individualized to name the persons who are to give reports and make recommendations. They may also include timelines that refer to specific topics, offer background information, and say when breaks will take place. RONR recognizes that every group has a personality of its own and should have the flexibility to express that personality through a well-crafted agenda tailored to meet its needs.

Making Decisions

Generally speaking, RONR specifies that decisions about proposals should be made as soon as possible after the proposals are made. For instance, if a recommendation is made during an officer’s report, it should be handled at that time.

Nothing may be decided in RONR unless a motionIn parliamentary terms, a proposal made by a member of a group to its chairperson for consideration by the group as a whole.—a formal proposal put forth orally by a participant in the meeting—has been made. The proper way to submit a motion is to say, “I move that…” (not “I make a motion that…”). Some groups may decide that any motion raised by a member will be deliberated, but RONR requires that nearly all motions receive a secondA statement by one member of a group indicating that he or she wants a motion just proposed by someone else to be debated. before the chairperson can proceed with the next step. That step is for the chairperson to “state the questionA formal announcement by the chair of a group indicating that a motion has been made and seconded and is open for debate.”—that is, announce to the group that a motion has been made and seconded and is open for debate. Details on exceptions to this process can be found in RONR itself, but the basic reason for requiring a second is to ensure that more than a single individual would like to consider a proposal.

Assuming that the person who submits a motion has done so according to the procedures of the group, the motion is considered to be pendingUnder debate. A pending question is one about which members of a group are expressing views at a given moment in a meeting., and its initial form it is referred to as the “main motionThe initial form of a motion proposed by a group member, prior to and independent of any amendments..” The chairperson is responsible for soliciting and guiding debate about any motion.

In the course of debate, the main motion may be amended or withdrawn, in part according to subsidiary motionsA motion related to a main motion, either to change it or otherwise alter its disposition. and in part according to the will of the person who originally proposed it. It’s also possible for a group to refer a matter to a subgroup or postpone discussion of it to a set time.

Generally, members should be recognized by the chairperson in the order in which they make it clear that they wish to speak. RONR stipulates that a speaker has up to 10 minutes each time he or she speaks and that the speaker isn’t permitted to “save” time or transfer it to another person. If a motion being considered in a large group is particularly controversial, the chairperson should make an effort to recognize proponents and opponents back and forth so as to ensure balance in the presentations.

When debate ceases on a motion, the chairperson should say “The question is on the adoption of the motion that…” and put the question to a vote of the membership. When the vote has been observed or tallied, the chairperson announces which side “has it”—that is, which side has won the vote. He or she then declares that the motion has been adopted or lost and indicates the effect of the vote, as necessary.

For instance, someone in a student committee might move that $250 be spent toward sending Jamie, its vice president, to a conference in New York City. After the motion has been seconded and debated, you as the chairperson might call for a vote and announce afterward, “The ‘ayes’ have it. The motion carries, and Jamie will receive $250 toward expenses for the trip to New York. Jamie, you’ll need to talk to Cameron, our treasurer, to get a check cut for you in advance of your travel.”

Being Civil

The point of following Robert’s Rules is to preserve order, decorum, and civility so that a group can make wise decisions. RONR allows a group’s chairperson to rule people’s comments out of orderIn parliamentary terms, inappropriate and unacceptable for further consideration. if the comments are irrelevant (not “germane”) or are considered to be personal attacks.

Robert’s Rules even makes provisions for group members to avoid direct attack. It attempts to accomplish this by allowing members of a group to refer to each other in the third person—e.g., “the previous speaker” or “the treasurer”—rather than by using each other’s names. Unfortunately, in long-established organizations such as the US Congress people sometimes get away with incivility even within such tight interpretations of the strictures of RONR. Consider the story, which may or may not be historically accurate, of two US Senators. Senator Smith had just spoken passionately in favor of earmarking funds to build a bridge across a certain river in his state. Senator Jones said, “That’s ridiculous. We don’t need a bridge there. I could pee halfway across that river!” Senator Smith retorted, “The previous speaker is out of order!” to which Senator Jones replied, “I suppose I am. Otherwise I could pee all the way across it.”

More Details

How punctiliously a particular group observes the requirements of RONR will depend on the group’s purposes, its level of formality, and sometimes even on the personalities of its members and leaders. One statewide college faculty organization in the Pacific Northwest prides itself on operating according to what it jocularly calls “Bobby’s Rules of Order,” although its bylaws stipulate that it is governed by RONR. The faculty organization has found for nearly 40 years that it can achieve its aims and maintain civility without observing many of the official trappings of RONR. Your group, on the other hand, may want and need the consistency and specificity of RONR to get its work done.

In any case, knowing the basic nature of Robert’s Rules and how to get guidance on its finer points can be advantageous to anyone who wants to promote efficient operations and decision-making by a group. In addition to referring to Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised In Brief, you may want to consult the website of the American Institute of Parliamentarians at http://www.parliamentaryprocedure.org for further information.

Key Takeaway

- Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised (RONR), a thorough and well-established system of parliamentary procedure, can be followed in greater or lesser detail as a group attempts to ensure civility, fairness, and efficiency in the conduct of its business.

Exercises

- Watch a broadcast on C-SPAN television of either the opening of a session of the US House of Representatives or of debate on legislation in the House or Senate. What specialized terms or forms of address did you hear which fit with your understanding of Robert’s Rules of Order? What function did those terms or forms of address fulfill?

- Locate a meeting agenda for a student group or employee committee on your campus. To what degree do its contents differ from the simplified standard order of business described in this section? Why do you think the organizers of the meeting modified the standard order as they did?

- Draft an agenda for a meeting of an imaginary student group and share it with 2–3 fellow students. Explain why you structured your agenda the way you did.

12.4 Post Meeting Communication and Minutes

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify a tool for recording and preserving notes of professional group conversations.

- Acquire a format for minutes which emphasizes actions taken by a group and the people assigned to accomplish them.

- Identify three ways in which a good group leader should follow up on meetings of the group.

Bookends hold books up. Without them, the books tumble onto each other or off the shelf. The “bookends” of a meeting, likewise, are as important as the meeting itself. Without them, nobody knows beforehand what’s going to happen or remembers afterward what did.

We’ve discussed the first major bookend of a meeting, its agenda. In this section we’ll turn our attention to the kinds of bookends that follow a meeting, including principally its minutes.

One Administrative Tool

A college administrator we know developed a form to give people after any conversation they had in his office, much less a formal meeting. He would take notes on the form of what he and the other people in the conversation said, and especially of what they agreed or disagreed on at the end of their meeting. Then he would share the notes with the other people, make a photocopy for each, and have them all initial their copies. Why? Because the administrator knew that busy people may quickly forget exactly what they decided in a conversation, or even what they talked about, unless they keep a shared record of what happened. Whether we like or believe it or not, our individual impressions of a meeting start changing and diverging the moment we leave the site. As one business writer noted, “Even with the ubiquitous tools of organization and sharing ideas…the capacity for misunderstanding is unlimited.”Matson, E. (1996, April-May). The seven sins of deadly meetings. Fast Company, 122.

The Why and How of Minutes

Among the exasperating experiences in group meetings are moments when people say, “We talked about this before—at least twice. Why are we going over the same ground again?” There are also those times when we hear, “John, you were supposed to report on this. What’s your report?” and John replies, “But I didn’t know I was supposed to make a report.”

The best way to prevent such deflating episodes is to follow up after each meeting with good records. Here are two ways to do this:

- Keep ironclad minutes. One college in Washington State has used this template for many years to shape and retain minutes of its academic committee meetings:

Date/time/location of meeting: ____________________________________

Purpose/goals of meeting: ____________________________________

Person presiding: ____________________________________

Officers in Attendance: ____________________________________

Other members in attendance: ____________________________________

Members absent: ____________________________________

Table 12.1 Agenda Template

| Agenda Item | Discussion/Motions | Action Taken | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Minutes | Approved as printed. | ||

| 2. Agenda | Approved as disseminated 5/29/2013. | ||

| 3. Roof problem | John Smith reported that the ceiling in the staff washroom leaks. Motion by Mary Jones to have the ceiling repaired; motion passed. | Plant/Maintenance will be asked to patch the leak. | John Smith will contact Jane Doe, head of Plant/Maintenance, by 6/15 to schedule repair. |

Time of adjournment: ____________________________________

Date/time/place of next meeting: ____________________________________

Notice that this style of minutes lacks extensive text and “he said/she said” descriptions.

Instead, it makes crystal clear who’s responsible for what actions prior to the next meeting. Its contents are brief, easy to read, and very difficult to misinterpret (or evade). It promotes action and accountability.

-

Distribute minutes promptly. When and how you disseminate minutes shows whether and how much you care about what your group does. If your group has bylaws, it may be a good idea for them to include a time frame within which minutes of meetings need to be distributed (such as “within five days”).

Make sure your mailing list of people to receive minutes is up to date and accurate. This will ensure that no one misses the next meeting because he or she didn’t see when and where it was scheduled to take place.

Sloppy minutes degrade the value of the work and time people invest together. They can also weaken a group’s morale. Professional minutes, on the other hand, may even make people who weren’t at a meeting wish they had been—although that’s perhaps asking a lot, unless you served pizza!—and can strengthen your group’s pride and solidarity.

What Else?

If you’re the leader of the group, making sure that minutes are prepared and distributed well is only one step toward increasing the likelihood that your meetings will achieve their full potential of transmitting discussions into plans and plans into action. You should do three other things after a meeting.

First, you should contact group members who were identified in the minutes as being responsible for follow-up action. See if they need information, resources, or other help to follow through on their assignments. If a committee or subcommittee was asked to take action on some point, get in touch with whoever heads it and offer to provide materials or other support that may be needed to accomplish its work.

Second, you should set a positive example. Take a few minutes to reflect on how effective you were in facilitating the last meeting and ask yourself what you might change at the next one. Be sure, too, to implement any decisions in a timely fashion that you as the leader were given.

Third, you should make sure that the minutes of your group’s meetings are stored in secure form, either physically or digitally or both, so that they are available to both you and other group members at any time. Your group’s institutional memoryShared remembrances among members of a group, which may or may not be recorded in physical form, of the group’s past., which is the foundation for future members to build upon, needs to be tended regularly and diligently. When in doubt, it’s better to hold onto information and documentation related to your group. Discarding something because you think to yourself “nobody will forget this” may very well turn out to be a mistake.

Observing these suggestions may not make the experiences associated with following up on group meetings heavenly, but it might at least keep them from being too hellish.

Key Takeaway

- After a group meets, its leader should ensure that professional minutes are disseminated and that other members of the group follow through with their responsibilities.

Exercises

- Pay special attention to conversations you carry on over the next several days in school and at home. Pick one of them and write simulated minutes according to the format shown in this section. What did you learn from this process about distilling and summarizing information from oral interactions?

- Locate a website of an academic, business, or civic organization which includes minutes of a recent meeting by some of its members. Identify portions of the minutes that you feel would enable you as a member of the group to adequately understand an important action taken by the group if you were unable to attend the meeting. If you were part of the group, what improvements would you make in the format of its minutes to further enhance their effectiveness?

12.5 Summary

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

In this chapter we have reviewed mechanisms and approaches to handling meetings. We have explored the purposes of meetings and discovered that alternatives to meetings can often yield satisfactory results within a group. We have reviewed specific steps in planning, facilitating, and following up after meetings, including the use of Robert’s Rules of Order. Meetings play a large role in the life and development of most groups, so acquiring tools for putting meetings to the best possible use can be of great value to their members.

Review Questions

Interpretive Questions

- Search the website of the Congressional Record at http://thomas.loc.gov/home/LegislativeData.php?&n=Record&c=111 for a legislative topic of your choice and locate 3–4 transcriptions of comments entered into the Record concerning it. What terminology or structure do you see in the text which differs from day-to-day conversational norms? What purposes do you believe these communication features might be intended to serve?

- If you’ve participate in a virtual meeting which reached a decision of some sort, what elements of the medium do you feel contributed positively to making the decision? What elements, if any, made it more challenging for you to achieve your aims?

Application Questions

- Think of a problem at your college that you and some of your fellow students feel needs to be addressed. Imagine that you’ve been told you have two weeks to present a proposal to the president of the college for remedying the problem. Draft an agenda for as many meetings as you feel would be necessary to involve the proper people in confronting the problem. Describe how the meetings would take place, including what rules you would follow, who would be invited, and what specific items would be dealt with in what sequence.

- Review the minutes of 3–4 recent meetings of a local governmental agency such as a city council or parks commission. What portion of the text in each set of minutes, if any, do you feel could be eliminated without diminishing the effectiveness of the documents as records of the meetings? Write up a revised version of one of the sets of minutes which most efficiently conveys what was important in the meeting.

Additional Resources

Books and Articles

Mosvick, R.K., & Nelson, R.B. (1996). A guide to successful meeting management. Indianapolis, IN: Park Avenue. Includes information about business meetings, along with suggestions on how to improve them.

Silberman, M. (1999). 101 ways to make your meetings active. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Provides fun activities and exercises to help prepare people to conduct meetings effectively.

Streibel, B.J. (2003). The manager’s guide to effective meetings. New York: McGraw-Hill. Includes advice on conducting virtual meetings, as well as useful examples and checklists related to meeting management.

Facilitation at a Glance; Ingred Bens

A wonderful pocket guide to facilitation, filled with tools and techniques useful to both novice and advanced facilitators. Great set of tools for problem solving.

Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making; Sam Kaner

An excellent resource for ideas on facilitation, with a focus on decision-making tools and techniques. The book includes excellent illustrations, which can be reproduced to help explain facilitation concepts to others.

Other Meeting Design and Facilitation Resources

The International Association of Facilitators (IAF)

The IAF promotes, supports and advances the art and practice of professional facilitation through methods exchange, professional growth, practical research, collegial networking and support services.

Interaction Associates

Interaction Associates is the creator and distributor of the Mastering Meetings: Tools for Collaborative Action and Essential Facilitation classes which MIT is licensed to teach. The Tips and Techniques section at their Web site is particularly useful.

12.6 Appendix A: Assessment of a Student’s Campus/Community Participation

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Dear Fellow College Employee:

Thank you very much for taking the time to assist a student in learning about the nature and functions of groups in our college and community. Please assess the student’s behavior candidly so s/he and I can make future student/employee encounters more positive and productive. Please return this form to the student so that s/he can learn from your comments. Again, thank you for your assistance!

STUDENT’S NAME: __________________________________

TWO ACTIVITIES YOU ATTENDED: __________________________________

Please place an “X” on the following scales to show your evaluation of the student’s behavior before, during, and after the interactions you’ve had with him/her:

1. The student approached me in a polite and courteous manner.

Strongly Disagree |______|______|______|______|______| Strongly Agree

2. The student explained the purpose of our prospective interaction well.

Strongly Disagree |______|______|______|______|______| Strongly Agree

3. The student’s questions were clear and easy to understand.

Strongly Disagree |______|______|______|______|______| Strongly Agree

4. The student thanked me appropriately for my time and assistance.

Strongly Disagree |______|______|______|______|______| Strongly Agree

What could the student do in future interactions with college staff, faculty, and administrators to increase his/her professionalism, clarity, or courtesy?

Your name: __________________________________ (Phone): _______________

For Students: Description of Interactions with a Faculty/Staff/Administrative Employee Contact

- How did you first contact the college employee? (i.e., by phone? face to face? by e-mail?)

- How did the person respond when you contacted him/her?

-

What two activities did you participate in with the employee?

Name/nature of activity #1: __________________________________ Date and time:___________________

Name/nature of activity #2: __________________________________ Date and time:___________________

- What actions did your Employee Contact take to help you prepare for your experiences together?

- What might have made the activities with your Employee Contact more educational for you?

- Check and explain how your experience with the Employee Contact helped you in the following areas:

| Yes | No | Comments/Explanations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I learned more about how our college functions | |||

| I learned how to act professionally in a business/educational/community organization | |||

| I met people who may help me in my future schooling | |||

| I met people who may help me in my future career | |||

| I learned these other things from my experiences: |

12.7 Appendix B: Critique of Formal Campus or Community Gathering

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

STUDENT’S NAME: __________________________________

Date: __________________________________

I attended a meeting/event of this group: __________________________________

on this date: _________________________ at this location: __________________________________

from ___________ a.m./p.m. to ___________ a.m./p.m.

My Employee Contact was: __________________________________ (Phone): _______________

The subject of the meeting/event was: __________________________________

The purpose of the meeting/event was: __________________________________

Name of the person leading the meeting/event: __________________________________

The person’s title within the group (e.g., president, chair, etc.): __________________________________

The person’s title at our college: __________________________________

At what time was the meeting/event scheduled to begin? __________________________________

At what time did the meeting/event begin? __________________________________

At what time was the meeting/event scheduled to end? __________________________________

At what time did the meeting/event end? __________________________________

Was an agenda used at the meeting/event? ______ YES ______ NO

[If an agenda was used, please attach a copy to this form]

How many people attended the meeting/event? __________________________________

What main topic(s) was/were discussed at the meeting/event? __________________________________

If the group made any decisions, please list them here:

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

What method(s) did the group use to make its decision(s)?:

______ Voice vote ______ Written voting ______ Consensus (“We all agree that XYZ”)

______ Other: __________________________________

______ Unsure of method

What particularly effective words, actions, stories, examples, or arguments stick in your mind from the event/activity?

Please place an “X” on the following scales to show your evaluation of the meeting/event:

Boring |______|______|______|______|______| Fascinating

Chaotic |______|______|______|______|______|| Well-Organized

Unintelligible |______|______|______|______|______| Clear / Easy to Understand

Routine |______|______|______|______|______| Controversial

The event/activity could have been improved by...

This is what I learned from the meeting/event that will make me a better student, employee, or citizen:

Other comments about the meeting/event: